Krakatoa

A 6,000-foot (above sea-level) volcano on Pulau Rakata Island in the Sunda Straits of Indonesia. At 10 a.m., on August 27, 1883, Krakatoa exploded, sending ash clouds to an altitude of 50 miles, and generating shock waves registered around the Earth several times. The detonation could be heard in Australia, 2,200 miles away. Some 5 cubic miles of rock debris were discharged, and ash fell over 300,000 square miles. The volcanic mountain collapsed into the sea, spawning tsunamis (destructive waves) as far away as Hawaii and South America, reaching heights of 125 feet, and claiming 36,000 human lives on Java and Sumatra. Krakatoa’s geological history not only makes the destruction of Atlantis credible through close comparison, but demonstrates how the Earth energies common to both events were brought about.

Krantor of Soluntum

A 4th-century neo-Platonist, a contemporary and colleague of Iamblichos, who played a important part in confirming Plato’s account of the sunken civilization by personally traveling to the Nile Delta, where he found the same Temple of the Goddess Neith, inscribed with identical information presented in the Dialogues.

Krimen

South America’s Tupi-Guarani Indians tell how three brothers—Coem and Hermitten, led by Krimen—escaped the Great Flood, first by hiding in caves high up in the mountains, then by climbing trees. As in the Greek version of Atlantis, the brother motif plays a central role.

Kritias

The second of two Dialogues composed by the Greek philosopher, Plato, describing the rise and fall of Atlantis, left unfinished a few years before his death in 348 b.c. The text is formed from a conversation (more of a monologue) between his teacher and predecessor, Socrates, and Kritias, an important fifth-century b.c. statesman. He begins by saying that the events described took place more than 9,000 years before, when a far-flung war between the Atlantean Empire and “all those who lived inside the Pillars of Heracles” (the Mediterranean) climaxed with geologic violence. The island of Atlantis, according to Kritias, was greater in extent than Libya and Asia combined, but vanished into the sea through a series of earthquakes “in a day and a night.” Before its destruction, it ruled over an imperial system from the “Opposite Continent” in the far west, to Italy in the central Mediterranean, including other isles in its sphere of influence and circum-Atlantic coastal territories.

The beginnings of this thalassocracy occurred in the mythic past, when the gods divided up the world between themselves. As part of his portion, Poseidon was given the Atlantean island. Its climate was fair, the soil rich, and animals— even elephants—were in abundance. There were deep forests, freshwater springs, and an impressive mountain range. The island was already inhabited, and Poseidon wed a native woman. The sea-god prepared a place for her by laying the foundations of a magnificent, unusual city. He created three artificial islands separated by concentric moats, but interconnected by bridged canals. At the center of the smallest, central island stood his wife’s original dwelling place on a hill, and it was here that the Temple of Poseidon was later erected, together with the imperial palace nearby.

Poseidon sired five sets of twin sons on the native woman, and named the island after their firstborn, Atlas. These children and their descendants formed the ruling family for many generations, and built the island into a powerful state, primarily through mining. The completed city is described in some detail, with emphasis on the kingdom’s political and military structures. Although their holdings kept expanding in all directions, the Atlanteans were a virtuous people ruled by a beneficent, law-conscious confederation of monarchs. In time, however, they were corrupted by their wealth and became insatiable for greater power. The Atlanteans built a mighty military machine that stormed into the Mediterranean World, conquering Libya and threatening Egypt, but were soundly defeated by Greek forces and driven back to Atlantis.

Kritias breaks off abruptly when Zeus, observing the action from Mount Olympus, convenes a meeting of the gods to determine some terrible judgement befitting the degenerate Atlanteans.

Kukulcan

The Mayas’ version of the “Feathered Serpent,” known throughout Middle America as the leading culture-bearer responsible for Mesoamerican civilization. According to their epic, the Popol Vuh, he was a tall, light-eyed, bearded, blond (“his hair was like corn silk”) visitor from his homeland, a great kingdom across the Atlantic Ocean. It reports that he arrived at the shores of Yucatan on a “raft of serpents,” perhaps a ship decorated with serpentine motif, or as Dr. Thor Heyerdahl suggested, a vessel whose reed hull twisted in the waves like writhing snakes.

Kukulcan was accompanied by a group of wise men who taught the natives astrology-astronomy, city-planning, agriculture, literature, government, and the arts. He put an end to human and animal sacrifice, saying that the gods accepted only flower offerings. Unfortunately, the Mayan words for “flower” and “human heart” were almost indistinguishable, and the Mayas eventually returned to human sacrifice and ritual removal of the heart. Kukulcan was much beloved and built the first cities in Yucatan. In time, however, he got into political trouble of some kind, and disgraced himself through drunkenness and sexual excesses, the common course of civilizers alone (or almost) among so-called primitive natives. He was forced to leave, much to the distress of most people. They wept to see him board his ship again, but he promised that either he himself or his descendant would come back someday. With that, he sailed, not to his homeland in the east, but into the Pacific Ocean, toward the setting sun.

Kukulcan was doubtless an important, though not the only nor necessarily the first, culture-bearer from Atlantis, probably before the final destruction of that city, because the Mayas’ account makes no mention of any natural disaster. They portrayed him in temple art as a figure supporting the sky , the archetypical Atlas. In any case, Kukulcan represents the arrival of Atlantean culture-bearers in Middle America.

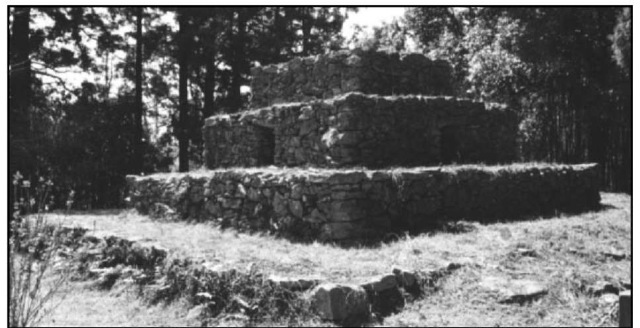

Lowland Yucatan pyramid dedicated to Votan, a flood hero from the Maya version of Atlantis, Valum.

Kuksu

Revered by South America’s Maidu and Pomo Indians as the creator of the world, he later, in response to the wickedness of mankind, set the Earth ablaze with celestial flames, then extinguished the conflagration with an awful deluge. Such native versions, while similar to the biblical version, differ importantly with the addition of a “fire from heaven” immediately preceding but inextricably bound to the flood.

A North American tribe known by the same name told of a turquoise house on a large island, long ago, on the other side of the western horizon. Before it was gradually engulfed by the Pacific Ocean, sorcerers who lived in the house took ship for California, where their descendants still make up a shamanistic society among the Kuksu.

Kumari Kandam

In Tamil tradition, the “Land of Purity,” a sophisticated kingdom of high learning, south of Cape Comorin, in the distant past. Like Mount Atlas, after which Atlantis derived its name, Kumarikoddu, the great peak of Kumari Kandam, gave its name to the “Virgin Land.” During a violent geologic catastrophe, Kumarikoddu collapsed into the Indian Ocean, dragging the entire island kingdom to the bottom of he sea. Survivors migrated to the subcontinent, where they sparked civilization in the Indus Valley.

Kumulipo

A Hawaiian creation chant in which the kumu honua, or origins of the Earth, are described in connection with a splendid island, where humans achieved early greatness, but were mostly destroyed by a terrible flood, “the overturning of the chiefs.” The Kumulipo is a folk memory of the Pacific Ocean civilization overwhelmed by natural catastrophe, as affirmed by repeated references to Mu.

Kung-Kung

A flying dragon in the Chinese story of creation, which caused the Great Flood by toppling the pillars of heaven with his fiery head. In the traditions of other ancient peoples, most particularly the Babylonians, sky-borne dragons are metaphors for destructive comets.

Kurma

The avatar of Vishnu, in Vedic myth, as a turtle in the “second episode” of the deluge story. Following the cataclysm, Kurma dove to the bottom of the sea, where he found treasures lost during the Great Flood. He returned with them to the surface, and led the survivors to life in a new land. Remarkably, his myth is virtually identical to numerous Native American versions—Ho Chunk, Sioux, Sauk, and so on—which refer to the North American Continent as “Turtle Island” after the giant turtle that saved their ancestors from drowning in the Great Flood.

Kusanagi

A magical sword originally belonging to Sagara, a dragon- or serpent-god living in an opulent palace at the bottom of the sea. It passed for some time among various members of Japan’s royal household, to whom it brought victory, but was eventually returned to its rightful owner. The Kusanagi sword appears to have been a mythic symbol for some technological heirloom from lost Lemuria. Sagara also possessed the Pearl of Flood, able to cause a terrible deluge at his command.

Kuskurza

Flood hero of the Hopi Indians in the American Southwest. He and his people fled the cataclysmic destruction of their magnificent homeland formerly located far out in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. As the flood began to rise, Kuskurza led them westward from island to sinking island until they reached safety on the eastern shores of North America. The Hopi account of what appears to be the Atlantean catastrophe reads in part, “Down on the bottom of the seas lie all the proud virtue, and the flying patuwvotas, and the worldly treasures corrupted with evil, and those people who found no time to sing praises to the Creator from the tops of their hills.”