Falias

One of four pre-Celtic ceremonial centers renowned for their splendor and power, sunk to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean during separate catastrophes. These lost cities correspond to Ireland’s four alien immigrations cited by The topic of Invasions and the quartet of cataclysms that afflicted Atlantis around 3100, 2100, 1620, and 1200 b.c. Gaelic tradition states that Falias was the original homeland of Ireland’s first inhabitants, the Fomorach, from whence they carried the Stone of Death, “crowned with pale fire.” It recalls the Tuoai, or “Fire Stone,” of Atlantis, as described by Edgar Cayce.

Fand

The Irish “Pearl of Beauty,” wife of a sea-god, the Celtic Poseidon, Manannan. They dwelt in a kingdom known as “Land-under-Wave,” on an island in the West, the concentric walls of their city lavishly decorated with gleaming sheets of precious metal virtually the same as Plato’s description of Atlantis. In the Old Irish legend of the Celtic hero, Cuchulain, Fand appears as a prophetess living alone in a cave on an island in the mid-Atlantic. Here she is identical to Calypso, the sibyl of Ogygia, a daughter of Atlas and, consequently, an “Atlantis.”

Fathach

The poet-king of Atlantean immigrants in Ireland, the Fir Bolg. From his name derived the Irish term for “Druid,” Fathi. Fathach may be one of the few words we know with any degree of certainty is at least close to the spoken language heard in Atlantis.

Fatua-Moana

“Lord Ocean,” who caused a worldwide deluge, but preserved some animals and a virtuous family from the calamity. When the waters abated, all other life had been drowned, and the survivors disembarked on the first dry land they saw, Hawaii. This pre-Christian version of the Flood is remarkably similar to the Genesis account of Noah, suggesting the Marquesas’ and biblical versions both stem from an actual natural catastrophe experienced in common.

Fenrir

A cosmic wolf that swallowed the sun at the time of the Great Flood, spreading darkness over the whole world. His Norse myth is a dramatic metaphor for the phenomenal clouds of ash and dust raised by the Atlantean cataclysm, which obscured daylight and plunged the Earth into temporary, but universal darkness.

Fensalir

“The Halls of the Sea,” the divine palace of the Norse Frigg, the Teutonic Fricka, or Frija, as Odin’s wife, the most powerful goddess in the Nordic pantheon. Fensalir may have been the Norse Atlantis.

Findrine

In a Celtic epic, The Voyage of Maeldune, the Irish explorer lands at a holy island with a city laid out in concentric rings of alternating land and water interconnected by a series of bisecting canals. Each artificially created island is surrounded by its own wall ornamented with sheets of priceless metals. The penultimate ring of land has a wall sheathed in a brightly gleaming, gold-like metal unknown to Maeldune, called “findrine.” The place he describes can only be Plato’s Atlantis, where the next-to-innermost wall was coated in orichalcum, a metal the

Greek philosopher is no less at a loss to identify, stating only that pure gold alone was more esteemed. Findrine and orichalcum are one and the same, most likely an alloy of high-grade copper and gold the Atlantean metallurgists specialized in producing because of their country’s monopoly on Earth’s richest copper mines, in the Upper Great Lakes Peninsula. (See Formigas, Orichalcum)

Finias

The sunken city from which Partholon and his followers arrived in Ireland from the second Atlantean flood, circa 2100 b.c. The sacred object of Finias was a mysterious spear.

Fintan

The leader of the Fomorach, a sea people who sailed from the drowning of their island home to the shores of Ireland. Fintan’s, along with that of his wife, Queen Kesara, may be among the few authentic Atlantean names to have survived. In celtic tradition, Fintan drowned in the Great Flood, and was transformed into a salmon. Following the catastrophe, he swam ashore, changed himself back into human shape, and built the first post-diluvian kingdom at Ulster, where he reigned into ripe old age. His myth clearly preserves the folk memory of Atlantean culture-bearers, some of whom perished in the cataclysm, arriving in Ireland. Remarkably, the Haida and Tlingit Indians of North America’s Pacific Northwest likewise tell of the Steel-Headed Man, who perished in the Deluge, but likewise transformed himself into a salmon.

Fir-Bolg

Refugees in Ireland from the early third-millennium b.c. geologic upheavals in Atlantis. Their name means literally “Men in Bags,” and was doubtless used by the resident Fomorach, themselves earlier immigrants from Atlantis, to excoriate the new arrivals for the hasty and inglorious vessels in which they arrived: leather skin pulled over a simple frame to form a kind of coracle, but the only means available to a people fleeing for their lives. The Fir-Bolg nonetheless reorganized all of Ireland in accordance with their sacred numerical principles into five provinces. According to Plato, the Atlanteans used social units of five and six.

The Fir-Bolg got along uneasily with their Fomorach cousins, but eventually formed close alliances, especially when an outside threat concerned the future existence of both tribes. The last Fir-Bolg king, Breas, married a Fomorian princess.

The Fir-Bolg joined forces with the Fomorach in the disastrous Battle of Mag Tured against later Atlantean immigrants, the Tuatha da Danann. Fir-Bolg survivors escaped to the off-shore islands of Aran, Islay, Rathlin, and Man, named after Manannan, the Irish Poseidon. The stone ruins found today on these islands belong to structures built by post-diluvian Atlanteans, the Fir-Bolg.

The Flood

See The Deluge.

Foam Woman

Still revered among the Haida Indians of coastal British Columbia and Vancouver Island as a sea-goddess and the patron deity of tribes and families. Foam Woman appeared on the northwestern shores of North America immediately after the Great Flood. She revealed 20 breasts, 10 on either side of her body, and from these the ancestors of each of the future Raven Clans was nurtured. In South America, the Incas of Peru and Bolivia told of “Sea Foam,” Kon-Tiki-Viracocha, who arrived at Lake Titicaca as a flood hero bearing the technology of a previous, obliterated civilization. Foam Woman’s twenty breasts for the founders of the Raven Clans recall the 10 Atlantean kings Plato describes as the forefathers of subsequent civilizations.

Fomorach

Also known as the Fomorians, Fomhoraicc, F’omoraig Afaic, Fomoraice, or Fomoragh. Described in Irish folklore as a “sea people,” they were the earliest inhabitants of Ireland, although they established their chief headquarters in the Hebrides. Like the Atlanteans depicted by Plato, the Fomorach were Titans who arrived from over the ocean. Indeed, their name derives fromfomor, synonymous for “giant” and “pirate.” According to O’Brien, Fomoraice means “mariners of Fo.” An Egyptian-like variant, Fomhoisre, writes Anna Franklin, means “Under Spirits.” In the Old Irish Annals of Clonmacnois, the Fomorach are mentioned as direct descendants of Noah.

Their settlement in Ireland, according to the Annals, took place before the Great Flood. They “lived by pyracie and spoile of other nations, and were in those days very troublesome to the whole world”—a characterization coinciding with the aggressive Atlanteans portrayed by Plato’s Kritias. The Annals’ description of the Fomorach’s sea-power, with their “fleet of sixty ships and a strong army,” is likewise reminiscent of Atlantean imperialism. They represented an early migration to Ireland from geologically troubled Atlantis in the late fourth millennium b.c, about the time the megalithic center at New Grange, 30 miles north of Dublin, was built, circa 3200 b.c.

Some 28 centuries later, the Fomorach were virtually exterminated by the last immigrant wave from Atlantis, the Tuatha da Danann, “Followers of the Goddess Danu,” at the Battle of Mag Tured. The few survivors were permitted to continue their functions as high priests and priestesses of Ireland’s megalithic sites, which their forefathers erected. This Fomorach remnant lived on through many generations to eventually become assimilated into the Celtic population, after 600 b.c. The most common Irish name is Atlantean. “Murphy” derives from O’Morchoe, or Fomoroche. The Murphy crest features the Tree of Life surmounted by a griffin or protective monster and bearing sacred apples, the chief elements in the Garden of the Hesperides.

Formigas

An Irish rendition of Atlantis found in the ninth-century Travels of O’Corra and Voyage of Bran. Formigas “had a wall of copper all around it. In the center stood a palace from which came a beautiful maiden wearing sandals of findrine on her feet, a gold-colored jacket covered with bright, tinted metal, fastened at the neck with a broach of pure gold. In one hand she held a pitcher of copper, and in the other a silver goblet.” Plato portrayed the Atlanteans as wealthy miners excelling in the excavation of copper and gold. The findrine mentioned here appears to be his orichalcum, the copper-gold alloy he stated was an exclusive product of Atlantis.

Fortunate Isles

Also known as the Isles of the Blest in Greek and Roman myth. They are sometimes used to describe Atlantis, such as during Hercules’ theft (his 11th labor) of the golden apples from the garden of the Hesperides that were protected by daughters of Atlas. In other contexts, the Fortunate Isles were believed to still exist, and seem to have been identified with the Canary Islands. Phoenician, Greek, and Roman amphorae have been found in the waters surrounding Lanzarote and other islands in the Canaries. The Fortunate Isles and Isles of the Blest were synonymous for the distant west and used as a metaphor for the afterlife.

Fountains of the Deep

German author Karl zu Eulenburg’s 1926 novel in which a passenger liner runs aground on Atlantis after a part of the sunken civilization rises to the surface. Die Brunnen dergrossen Tiefe is an original, imaginative tale.

Frobenius, Leo

Early 20th-century German explorer and founder of modern African studies. His pioneering collection of Yoruba oral traditions describing a catastrophic flood in the ancient past and subsequent migration of survivors, together with anomalous bronze manufacture among the Benin, convinced Frobenius that native West Africans preserved folk memories of Plato’s Atlantis.

Fu Sang Mu

In Chinese myth, a colossal mulberry tree growing above a hot “pool” (sea) in a paradise far over the ocean, toward the east. The land itself is hot. No less than nine suns perch in Fu Sang Mu’s lower branches. White women renowned for their beautiful, long hair tend the li chih, or “herb of immortality,” in a garden at the center of the island. The lost Pacific civilization of Mu was chiefly characterized by a sacred Tree of Life, and its climate was said to have been very hot.

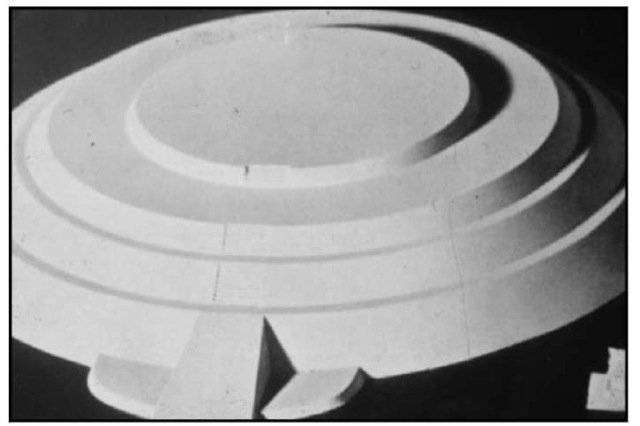

Restoration of the Cuicuilco Pyramid in this Mexico City Museum model reveals its concentric design, a hallmark of Atlantean monumental construction.