Enki

In Sumerian myth, a sea-god who traveled on a worldwide mission to civilize mankind in his great ship, The Ibex of the Abzu. Like the Egyptian Ausar, the Greek Osiris, Enki was a pre-flood culture-bearer from Atlantis. The Abzu was the primeval waste of waters out of which arose his “Mountain of Life.”

Enlil

The Sumerian Atlas, known as the Great Mountain, who held up the sky. Enlil was famous as the conqueror of Tiamat, the ocean, just as Atlantis dominated the seas. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, where he is known as Bel, Enlil is responsible for the Deluge.

Enuma Elish

A poem dramatizing the Deluge from which the Oannes “fish-men” crossed the sea to establish civilization throughout Mesopotamia. The Enuma Elish was recited during each New Year’s festival at the Sumerians’ Easgila ziggurat, itself dedicated to the sunken realm of their ancestors.

Eochaid

King of the Atlantean Fomorach, who defeated later invaders from Atlantis, but was murdered under treacherous circumstances. (See Fomorach, Nuadu)

Esaugetuh Emissee

The Creek Indians’ “Lord of the Wind,” like the Aztec Ehecatl, the Sumerian Enlil, the Egyptian Shu—all ethnic variations of Atlas. In his creation legend, Esaugetuh Emissee escaped a universal flood by climbing to the summit of a mountain at the center of the world, Nunne Chaha. As the waters receded, he fashioned the first human beings from moist clay.

Nun was the Egyptian god of the Primeval Sea, out of which arose the first dry land, sometimes described as a “sacred mound” or mountain, where the earliest humans were created. It also gave birth to the gods during the Tep Zepi, or the “First Time.” Nun was represented in temple art as a man plunged to his waist in the ocean, his arms upraised to carry the solar-boat with its divine and royal passengers. He held them above the Flood engulfing their mountainous homeland in the Far West, and brought them to the Nile Delta, where they reestablished themselves in Dynastic civilization. Nun saved both gods and mankind from the same disaster he caused at the behest of Atum, who had commanded a great deluge to wash away the iniquities of the world.

The Sumerian Ninhursag, “Nin of the Mountain,” arose out of the Abzu, the Primordial Sea, to create an island blessed with all kinds of herbs, wine, honey, fruit trees, gold, silver, bronze, cattle, and sheep. But when Enlil, like the Egyptian Atum, ordered a Great Flood, Ninhursag sank under the waves of the Abzu. The god who actually caused the Deluge was Ningirsu, “Lord of Floods.” Enlil’s wife was Ninlil, the sea, mother of all. Ninazu, the “Water Knower,” dwelt in Arallu (the Egyptian Aalu, the Greek Atlantis). In Phoenician, the word for “fish” was nun.

The Norse Ginunngigap was the sea that swallowed the world and doomed to repeat the catastrophe at cosmic intervals for all eternity. The Ginunngigap, too, was said to have brought forth the first land on which humans appeared.

The Native American Nunne-Chaha could not be clearer in its reflection of the “Nun” theme threading its Atlantean story from Egyptian and Sumerian through Phoenician and Norse myth. Nunne Chaha was the “Great Stone House” on an island in the primeval Waste of Waters. The island was said to have been surrounded by a lofty wall, and watercourses were directed into “boat-canals.”

The Egyptian Nun was also known as Nu, and Nu’u was responsible for the Hawaiian Po-au-Hulihia, the “Era of the Over-Turning,” the great flood of Kai-a-ka-hina-li’i, “the Sea that made the Chiefs fall down.”

Escape from Atlantis

A 1997 feature film, in which the protagonists sail through the Burmuda Triangle, and are suddenly transported back to Atlantis. Escape from Atlantis is one of several Hollywood movies (including Cocoon, for example) based on the premise that Atlantis lies in the Bahamas.

Etelenty

Ancient Egyptian for “Atlantis,” as it appears in The topic of the Coming Forth by Day, better known today as The topic of the Dead—a series of religious texts buried with the deceased to help the soul along its underworld journey through death to its spiritual destiny. According to Dr. Ramses Seleem’s 2001 translation, “Etelenty” means “the land that has been divided and submerged by water.” Its Greek derivation is apparent, and was probably the same term Solon heard spoken at Sais, which he transliterated into “Atlantis.”

Etruscans

The pre-Roman people who raised a unique civilization in west-central Italy, circa 800 b.c. to 200 b.c. Although racially Indo-European, their largely untranslated language was apparently related to Finno-Urgic, making them distantly related, at least linguistically, to Hungarians, Estonians, and Finns. They referred to themselves as the Rasna; “Etruscan” was the collective name by which the Romans knew them because of their residence in Tuscany. Their provenance is uncertain, although they appear to have been a synthesis of native Italians, the Villanovans, circa 1200 b.c., with foreign arrivals, most notably from northwest coastal Asia Minor.

Trojan origins after the sack of Ilios, formerly regarded by scholars as entirely fanciful, seem at least partially born out by terra-cotta artifacts featuring Trojan motifs. Etruscan writing compares with examples of Trojan script, and Aeneas’ flight from Troy appears in Etruscan art.

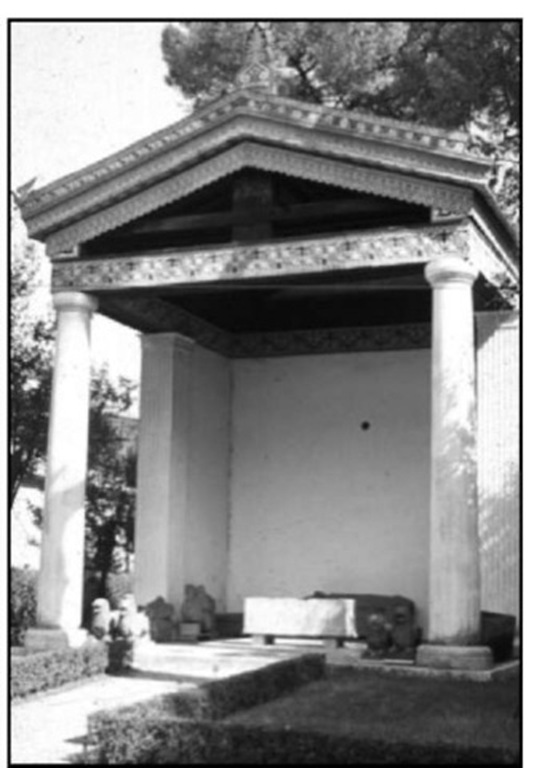

Recreation of an Etruscan temple, Via Guilia Museum, Rome, that resembled Atlantean counterparts.

In Plato’s Kritias, we read that Atlantean expansion extended to Italy, and specifically, that Etruria came under the influence of Atlantis. Some significant Atlantean themes survive in Etruscan art, such as the large terra-cotta winged horses of Poseidon at Tarquinia. Some scholars suspect that the name “Italy” is Etruscan. If so, it is another link to Atlantis, because Italy is a derivation of Italus, or “Atlas.”

Euaemon

A king of Atlantis mentioned in Plato’s account, Kritias. In non-Platonic Greek myth, Euaemon married Rhea—after her husband, Kronos, was banished by the victorious Olympians—and fathered Eurylyptus, the king of Thessaly. Several elements of the Atlantis story appear even in this brief legend. Kronos was synonymous for the Atlantic Ocean, “Chronos maris” to the Romans. Rhea was the Earth Mother goddess, referred to as Basilea by the lst-century b.c. Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, who reported that she had been venerated by the Atlanteans. They probably knew her by names mentioned in Kritias: either Leukippe, Poseidon’s mother-in-law, or Kleito, the mother of Atlantean kings.

Euaemon’s role as a progenitor of Thessaly’s royal lineage is likewise in keeping with the tradition of Atlantean monarchs as far-flung founding fathers. Euaemon has an intriguing connection with the Canary Islands, where the Guanche word for “water” was aemon. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, the Arawak Indians of coastal Venezuela and Colombia believed a god called Aimon Kondi drowned the world to punish the wickedness of men.

But Euaemon appears to be most closely identified with Eremon, the founder of a united, pre-Celtic Ireland. His similarity with the fourth monarch of Atlantis is more than philological. Long lists of regents’ names were kept in ancient Ireland by successive generations of files, or poet-historians. They traced each ruler’s line of descent from Eremon as a means of establishing royal legitimacy. In the topic of Invasions, a medieval compilation of oral traditions rooted in early Celtic and pre-Celtic times, Eremon is described as the leader of a “Sea People” who landed on Irish shores in 1002 b.c. The date is interesting, because it is precisely 200 years after the final destruction of Atlantis in the Bronze Age. These relatively close time parameters and Eremon’s appearance in two unrelated ancient sources on either side of Western Europe, together with his Irish characterization as the king of a “Sea People” arriving as refugees in a pre-Celtic epoch, clearly define him as an Atlantean monarch.

Eremon was said to have sailed to Ireland with fellow storm-tossed survivors after an oceanic catastrophe that drowned most of his people, known as the Milesians. Though originally founded by an earlier race, the seat of Irish kings, Tara, was named after Eremon’s wife. She herself was a daughter from the royal house of the Blessed Isles lost beneath the sea. All these native elements remarkably combine to identify themselves with Plato’s account. His Euaemon was doubtless the Eremon of Irish tradition.

Eumelos

According to Plato in Kritias, the Greek name for Gadeiros, an Atlantean monarch in Spain.

Eupolemus

A first-century b.c. Greek author of a lost history of the Jews in Assyria. Surviving fragments tell how Babylon was founded by Titans after the Great Flood. They built the so-called “Tower of Babel,” destroyed by a heavenly cataclysm which dispersed them throughout the world. In Greek myth, Atlas was leader of the Titans. The cometary destruction of Atlantis, his island kingdom, and flight of his people across the globe are represented in the fate of the Tower of Babel.

Evenor

“One of the original Earth-born inhabitants” on the island of Atlas, according to Kritias. “Evenor” means “the good or brave man,” who lived and died before Atlantis was built. Evenor’s myth implies that his homeland had a human population previous to the development of the megalithic pattern upon which the city was raised. This means that the island was at least inhabited in Paleolithic times, during the Old Stone Age, 6,000 or more years ago. We may likewise gather that the original creation of Atlantis was a product of Neolithic megalith-builders, thereby dating its foundation to circa 4000 b.c. However, it almost certainly began as a ceremonial center, like Britain’s Stonehenge. As it grew over time, the sacred site expanded to become, in its final form, a Late Bronze Age citadel and city.

There is something singularly provocative in Evenor’s story, because it relates that civilization was not native to his island, but an import. His daughter, Kleito, married Poseidon, an outsider, who came from across the sea to lay the concentric foundations of the city. In other words, an external influence initiated its construction, perhaps by culture-bearers from some community older even than Atlantis itself. Civilization, at least as it came to be known after 3000 b.c., may have first arisen on the island of Atlas, but seafaring megalith-builders from another unknown homeland may have arrived to spark its Neolithic beginnings.

Modern Berber tribes of North Africa still preserve traditions of Uneur and his “Sons of the Source,” from whom they trace their lineage. Evenor and Uneur appear to be variations on an original Atlantean name.

Exiles of Time

A 1949 novel about Mu by Nelson Bond. In his destruction of the Pacific realm through the agency of a comet he anticipated late 20th-century scientific discoveries concerning impact on early civilization by catastrophic celestial events.