In This Chapter

Looking beyond medication alone

Identifying the goals of psychosocial treatments

Understanding new developments in individual, group, and family therapies

Addressing the vocational, social, and thinking skills deficits associated with schizophrenia

Recognizing the roles of self-help and family psychoeducation

It would be wonderful if all the symptoms and signs of schizophrenia could be whisked away by merely swallowing a pill. Unfortunately, even the best medications alone aren’t a cure-all. While medication is essential to treat and control acute positive symptoms (see Chapter 8), medication alone falls short in helping the person with schizophrenia regain his sense of self-worth and his ability to function in society after a first psychotic break or a recurrent psychotic episode.

The losses associated with an acute episode of schizophrenia can be devastating. Medication — although it can usually help stabilize symptoms so life is more “normal” — can’t erase the pain of feeling stigmatized, left out, and unable to cope with tasks that seem to come easily to peers, such as living independently or holding down a job.

In this chapter, we identify and explain the array of psychosocial treatments, therapies, and approaches — beyond medication — that should be available as part of a comprehensive system of care for people with schizophrenia. These include psychological, rehabilitative, and cognitive therapies, along with self-help and family approaches, that lessen positive symptoms, improve thinking and social skills, reduce the risk of relapse, and improve quality of life.

Although any one individual may not need or use all these approaches, every community should have them available for those who need them.

Unfortunately, many psychosocial therapies are not available in every community. One of the best ways to get a handle on what exists in your community is by asking a case manager or social worker. You or your loved one can also contact your state or local mental-health authority (see the appendix) and find out about the availability of programs in your geographic area.

Because of the complexity of the mental-health service system, many private practitioners aren’t likely to know about the full range of psychosocial rehabilitation services available in their own communities.

Understanding Psychosocial Therapies

We use the term psychosocial treatments to describe the psychological, social, and combined psychosocial approaches (usually used in conjunction with medication) that aim to help people improve their current level of functioning so it is the best that it can be — so they can feel productive and good about themselves (see Chapter 15).

Psychosocial treatments are aimed at:

Lessening the symptoms and impairments caused by the disorder

Helping people better manage their illness, which includes teaching them how to:

Recognize and cope with persistent symptoms of the illness (such as hearing voices or being unable to concentrate)

Maintain a consistent medication regimen

Monitor and cope with the potential side effects of treatment

Prepare for and prevent (to the extent possible) recurring episodes

Helping people achieve social, academic, training, or vocational goals Helping people learn or relearn practical life skills, such as:

Managing money

Housekeeping

Shopping

Doing laundry

Keeping up with basic hygiene and maintaining their personal appearance

Navigating public transportation

Teaching people ways to decrease stress, avoid conflict, and manage anger

Helping people reconnect with others

Helping people understand and cope with their diagnosis as they move toward recovery (see Chapter 15)

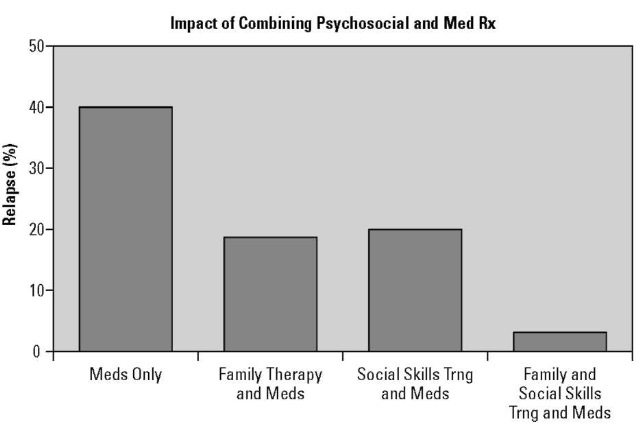

Evidence shows that adding psychosocial treatments to medication therapy results in better outcomes than either medication alone or psychosocial therapy alone. For example, people who are treated with a combination of medication, social skills training, and family therapy have only a 5 percent chance of relapse, compared to a 40 percent chance of relapse among those treated with medications alone (see Figure 9-1).

Taking advantage of various psychosocial approaches isn’t a matter of choosing one over another, or using them as substitutes for medication. For the practical and optimal treatment of schizophrenia, it’s advantageous to combine medication and psychosocial approaches that enhance once another.

Figure 9-1:

Relapse rates are lower when people aren’t treated only with medications.

When talk was king

Psychotherapy (talk therapy) is what most people think of when they picture treatment for mental illness: the patient lying on the couch, recounting everything she can remember happening to her since she was an infant or toddler, while the psychiatrist sits, stone-faced and silent, listening until the patient finally reaches some catharsis (emotional cleansing) of feelings and insight into her behavior. About half a century ago, before the widespread use of psy-chopharmacology (medications), psychotherapy was the prominent, dominant, and almost universally accepted treatment for all psychiatric illnesses, including schizophrenia.

Then medications appeared that, at least in many people, seemed to work like magic. Talk therapy was outdated; the remedy was in the tablet. Medications can have near miraculous results in reducing psychosis. However, the person affected still has to pick up the pieces of his life and try to put them back together. This is something medication can’t help with. It takes another person — or a group of people — to help the person with schizophrenia find ways to become a functioning member of society again.

Today a combined approach is seen as what’s needed: keeping psychotic symptoms under control with medications, supportive therapy that is focused on problem-solving, psychoso-cial approaches to help the patient regain independence, and self-help to enable an individual to regain his confidence, sense of self-esteem, and hope for the future. When talk therapy is used today, it takes a different form: It’s usually briefer, more practical and supportive, and focused on specific goals.

It’s worth noting, too, that the past half-century has seen significant advances in psychological therapies. The psychoanalytic theory monopoly was broken, and different kinds of therapies surfaced. In general, the newer therapies centered more on practical rehabilitation of the individual, in much the same way that someone is rehabilitated after a physical injury (such as a broken arm or a stroke), instead of trying to solve the puzzle of finding the root causes of someone’s illness in her history.

Individualizing a plan for treatment

Each person with schizophrenia has different needs, and the same person has different needs at different points in her illness. Treatment planning needs to be flexible enough to adapt to these changes. For example, right after hospital discharge, your loved one’s major challenges may be to cope with positive symptoms — and a combination of cognitive behavioral therapy and family psychoeducation may be very helpful. When those challenges are met, your loved one may be ready to prepare for a job and be in a position to benefit from social skills training and vocational rehabilitation.

One important purpose of an individualized plan is to identify ways to monitor and reduce stress so the person with schizophrenia doesn’t take on too much too soon. Typically, schizophrenia occurs at a phase of life when people are building their lives and careers, so they may feel a sense of urgency to resume school full-time to make up the courses they missed or to go back to work before they lose their job or housing. Like medicine, psychosocial rehabilitation needs to be sensitively and intelligently dosed and monitored.

As with most things in life, timing is everything, and it certainly is an important consideration in determining the phasing of treatments for patients with schizophrenia. When someone is severely psychotic (with symptoms that may include hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thinking, and agitation), it makes no sense to try to teach social skills or to try to decrease denial and improve insight with psychotherapy. Likewise, when acute positive symptoms are largely controlled and a person with schizophrenia is feeling lonely and would like to have a job and a fuller life, it won’t do much good to merely adjust one or more medications. Together, the individual, the clinician, and the family need to decide on the timing and selection of the correct mix of interventions to meet their mutual goals.

Schizophrenia is a persistent (chronic) illness that periodically worsens (a condition called relapse) and then improves (a condition called remission). Thus, the treatment needed varies with the phase of illness, the nature of the problems, and the individual’s stage of recovery (see Chapter 15). Each person with schizophrenia faces unique difficulties and changing circumstances that require different approaches at different times.

Both clinicians and case managers play an important role in coordinating the participation of everyone who needs to be involved in the design of an individualized plan that assesses your loved one’s needs and helps identify resources for its implementation. It doesn’t stop there. The plan needs to be modified, as appropriate, over time as circumstances change.

The staff of local psychosocial rehabilitation programs — which are often funded by government, the private sector (usually nonprofit), or multiple sources of funding — can also take the lead in developing individualized plans for consumers that take advantage of the various resources available in the community.

After a psychotic break, many patients and their families want to plunge right back into normal life and make up for lost time. Others may be so devastated by the illness that they’ve lost all hope and think there’s no way out. In either situation, a solid psychosocial evaluation and development of a comprehensive plan for treatment can help individuals and their families control symptoms — and simultaneously identify and set realistic goals for treatment and recovery.

Clearly, research shows that combining psychosocial treatments with medication improves outcomes compared to medication or other biological treatments used alone. One of the limitations of research on psychosocial treatments, which is common to treatments in general medicine as well as psychiatry, is that scientists still don’t know what approaches work best, for which individuals, at various phases of the illness.

Certainly, we can say that the field has evolved greatly over the past two decades with a greater range of approaches being implemented and studied in local communities. We’re better able to identify the full range of deficits associated with schizophrenia and to evaluate which deficits and skills are compromised for a particular individual.

The choice of psychosocial treatments should be linked to the individual needs of the patient. Not too far in the future, the hope is that we will minimize deficits through early recognition and treatment and that people with schizophrenia will be able to take advantage of treatments that are individualized and personalized for them.

Understanding what psychosocial rehabilitation can do

People with schizophrenia face many challenges after an acute episode has subsided and they are psychiatrically stable. Psychosocial rehabilitative interventions can be instrumental in providing the tools, training, and experience people with schizophrenia need to solve problems, manage their illness and its treatment, and create and nurture social and vocational skills, with coordinated planning by professionals, family members, and consumers.

For example, although antipsychotic medications are essential in bringing the acute symptoms of schizophrenia (such as hallucinations and delusions) under control — for many, these drugs may not completely eliminate symptoms. This means that some people may need to learn how to live with persistent voices in their heads, find ways to express themselves more coherently, learn how to distinguish between seeing things that are real and those that aren’t, and learn how to contend with the real losses they’ve endured as a consequence of their illness.

Also, the side effects of taking medications can add a new set of problems. The same drugs that provide hope for recovery may leave patients with uncomfortable, potentially unhealthy and/or disabling side effects — such as dry mouth, drowsiness, weight gain, diabetes, tremors, loss of sexual desire, or insomnia — which may then need to be dealt with.

Many people with schizophrenia have lost some or all the roles that define them in society. They may no longer have a socially acceptable answer to the common question, “What do you do?” Rehabilitative therapies are designed to build a bridge between a person being sick (and doing very little) and being able to return to homemaking, school, training, employment, or some other meaningful activity — activities that are vital to a sense of satisfaction and self-worth.

Building or rebuilding vocational/occupational skills

Even when a person with schizophrenia is eager to work, time off for hospitalizations or acute episodes at home not only creates holes in a resume, but also can lead to deficits in a person’s skills and job performance. Because the onset of the disorder commonly occurs in adolescence or young adulthood, the individual may not have had the opportunity to acquire technical or other work skills and may have had little or no experience with the rigors of maintaining a 9-to-5 job.

A person with schizophrenia can face many vocational challenges:

‘ Not having a driver’s license, not having a car, or having a hard time learning the bus route to work.

Not having marketable job skills or training. (One patient we knew had learned how to do complex math algorithms in college, which were no longer used because the work could be done more quickly by computer.)

Having his education interrupted or halted prematurely in high school or college because of the illness.

Having little or no work experience, unexplained gaps in employment, or no references.

Not knowing how to go about looking for a job. Not knowing how to prepare a resume.

Not being able to interview well because of limited social skills.

Having a hard time adjusting to the rigors of an office or other workplace setting (for example, getting there on time, punching a time clock, working at a sustained pace, following instructions, working a full shift).

Worries about potential loss of Social Security benefits (which are based on the inability to hold a competitive job).

There are ways to protect benefits during trial work periods (see Chapter 15).

Transitional or supported employment programs are generally time-limited efforts to help restore the skills and confidence people need to return to productive employment. The beauty of these programs is that the person with schizophrenia gets support from the program and from an employer who understands the nature of her new employee’s history and/or limitations and who has an expressed desire to provide support and help.

Many of these programs employ job developers who work with industry to create employment slots for people with disabilities. These may be full-time jobs or part-time opportunities that can help people ease their way back into the workplace. Sometimes, programs even provide a coach who will accompany the individual on-site to train individuals and monitor their work.

Through the Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA) of the U.S. Department of Education, every state receives funds to provide employment-related services — such as counseling, job training, education, supported employment, and so on — to assist individuals with physical or mental disabilities. Although waiting lists may be long and the programs aren’t specifically geared to people with mental disorders, these resources shouldn’t be overlooked because they can provide invaluable support. To find the agency in your own state, do an online search for vocational rehabilitation and the name of your state.

Participation as an unpaid volunteer in the community is another low-pressure way to ease back into the world of work and give your loved one the feeling that she’s able to contribute to others.

Easing the loneliness and social isolation of schizophrenia

One common problem for people with schizophrenia that can be addressed through psychosocial therapies is loneliness. It’s a human instinct to want to connect with other people, and families and friends experience great pain when they witness the isolation of a loved one with schizophrenia. Both the disease and the treatment of schizophrenia make it more difficult to make and keep friendships.

Being in and out of hospitals, in and out of schools, or in and out of work can lead people with schizophrenia to be out of sync or to lose contact with their peers. A student may have dropped out of college because of the illness and lost contact with roommates and classmates, or a person may have lost his job because of the illness and be too embarrassed to reconnect with former coworkers or supervisors.

Additionally, the positive and negative symptoms of the disease (see Chapter 3) itself may make it uncomfortable to be around people. It’s not uncommon for people with schizophrenia to:

Hear voices while someone else is to talking to them. This can be confusing for them, making it hard to focus on what the other person is saying and causing them to be slow in responding.

Feel suspicious, be wary of new people, and inaccurately perceive that people they know are thinking or reacting negatively to them.

Be highly distractible because of their inability to focus (due to voices, hallucination, depression, or anxiety).

Have no motivation or low energy (because of negative symptoms).

This can result in the person with schizophrenia having no interest in forming or maintaining social ties.

Be too irritable, anxious, or depressed. This makes it uncomfortable for them to be around others and for others to be around them

‘ Have low self-esteem because of their diagnosis and its stigma or be embarrassed by the side effects of medications (such as significant weight gain or tremors).

Act inappropriately because of cognitive and social deficits, which cause people to rebuff their efforts or feel frightened of them. For example, a person with schizophrenia may stand too close to people, be unable to discern what to say or what not to say, ask invasive questions, be unresponsive, have an unkempt appearance, or exhibit other odd behaviors.

Have a hard time adapting to large-group situations and find them stressful.

Feel discomfort and guilt about not knowing who to tell or not to tell about their illness. For example, should you tell a date? An old classmate? (For more on breaking the news, see Chapter 11.)

Because of these residual symptoms, some people with schizophrenia have a hard time being around other people with the same illness (because they serve as constant reminders of their own illness), have social anxiety (an out-of-proportion fear of being evaluated by people around them), or just don’t feel like they fit in with other more “normal” people who don’t understand their challenges. (On the other end of the spectrum, some people feel more comfortable socializing with others who are experiencing and overcoming similar challenges; see “Self-help groups,” later in this chapter.)

In either case, even on a practical level (because of the impact of the illness on their finances) they may not have the pocket change they need to pay for dinners out, going to a movie, public transportation, the supplies needed for a hobby (like painting or photography), or the membership fees to join a health or fitness club.

Family relationships, especially sibling ones, may be strained because either the family hovers over the ill individual too much in an effort to encourage the person to be more social or excludes him from family functions to avoid discomfort for the individual and everyone else. Cumulatively, all these factors leave a person with the illness feeling detached and lonely, which can be ameliorated by various psychosocial interventions.

Learning new skills and relearning forgotten ones

Psychosocial skills training is a structured educational approach that usually takes place in groups that are focused on specific objectives for a set number of sessions. The skills are ones that are relevant to helping a person with schizophrenia better function as a member of her community. Training may cover:

Activities of daily living Assertiveness

Social skills and basic conversation skills

Use of leisure time

Money management

Symptom and medication management

Accessing Social Security and other benefits

The training is usually preceded by an evaluation, either one that’s done by a trained observer or by self-report (for example, the consumer is asked to fill out a questionnaire describing his own limitations). Larger tasks are broken down into smaller ones and various behavioral approaches are used including role playing, modeling, and positive reinforcement (often in the form of food or drink). For example, if someone were learning how to present himself for a job interview, the training might focus on how to shake hands, how to make eye contact, what to say, what to ask, and how to dress.

Research suggests that skills training improves social skills, assertiveness, and readies people to leave hospitals sooner after a prolonged hospitalization.

For almost three decades, the U.S. government — first through the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and then through the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) — jointly with the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR) of the Department of Education, has supported the growth of the Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation at Boston University (www.bu.edu/cpr). This national center supports research, training, and services that are focused on helping people achieve “a decent place to live, suitable work, social activities, and friends to whom they can turn in times of crisis.” The Center’s Web site has a wealth of resources suitable for consumers, families, and professionals.

The National Research and Training Center on Psychiatric Disability, located in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Illinois in Chicago (www. cmhsrp.uic.edu/nrtc) is a sister center, funded by the same federal agencies as the NIDRR. Its Web site offers free online workshops, Webcasts, and online continuing education courses.

Centers targeting the needs of children and adolescents with psychiatric disability are located at the University of South Florida (http://rtckids. fmhi.usf.edu) and Portland State University (www.rtc.pdx.edu/ index.php).

One of the more successful approaches to psychosocial rehabilitation is the assertive community treatment (ACT) program (see Chapter 5). ACT programs provide intensive outreach and care to help people live independently in their own homes. Trained professionals are available 24/7 to help individuals gain the practical skills they may have lost or never learned. They also oversee medication, making sure that medical and psychosocial care is coordinated for severely ill people in the community.

Looking at Individual Therapies

Individual therapies are one-on-one approaches with a clinician working directly with a client. Three of the most common therapies practiced one-on-one are psychodynamic therapy, supportive therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy. We cover each of these in the following sections.

Psychodynamic therapy

Although psychodynamic therapy (meeting with a therapist on a regular basis over a long period of time to get to the root of a problem) was the dominant therapy for the first 50 years of the 20th century — think Woody Allen— these treatments weren’t scientifically evaluated during their heyday. In fact, there’s still no credible evidence that they’re specifically beneficial in treating the symptoms or impairments associated with schizophrenia.

One problem is that the cognitive and memory deficits associated with schizophrenia can interfere with the ability of the person to benefit from this kind of therapy. (In fact, all psychosocial treatments must overcome this hurdle to be effective. People with schizophrenia must be able to understand and actively participate for any treatment to be helpful.) Thus, psychody-namic therapy is usually used for people with psychiatric disorders whose thinking remains intact.

Supportive therapy

People with schizophrenia, contending with many real-life problems, need someone experienced to talk to. Supportive therapy (therapy conducted by a professional trained to work with people with serious mental illnesses) is an important complement to medication and other psychosocial treatments. In these days of managed care, the time allowed for patients and their psychiatrists to spend with each other is often rationed by insurers and other third-party payers.

Therefore, it is important that your loved one has a trained professional as part of his team, with whom he can openly discuss his problems and find ways to overcome them. For example, if a person with schizophrenia was having problems making friends, the therapist might help her find ways to meet people and make the first overture.

Having such a safe, supportive relationship to learn new ways of coping is vital to recovery. This can be especially valuable for people who have trouble opening up to a group. Even though family and friends may be supportive, they aren’t trained for and are usually too emotionally involved to play this role.

Psychologists, social workers, or other counselors who work with people with schizophrenia can help them cope with stressors in their lives, encourage adherence to treatment, help patients determine other needed treatments and supports, and serve in the role of a coach — providing encouragement and support. Psychotherapy can also be useful to over-stressed loved ones who are unable to cope with the impact of the diagnosis on their own lives.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is usually conducted on a one-on-one basis in an outpatient setting, usually by a trained therapist, but it also can be practiced in groups. Like any individual therapy, CBT requires close collaboration between a patient and therapist. Therefore, it’s important to interview the therapist before your loved one starts treatment, to make sure your loved one feels comfortable working with that individual (see Chapter 5).

When selecting a therapist for individual therapy, it’s always prudent to ask for referrals from people you trust and to consider the first few sessions as an interview to get a good sense of the individual, whether your loved one connects with him, and whether it seems like talking with this person will be helpful.

CBT was originally developed in the late 1970s for the treatment of people with depression and anxiety disorders. At that time, it was the most proven psychosocial intervention, and even though it was not originally used for treating schizophrenia, there’s now convincing evidence for its effectiveness, especially in reducing positive symptoms that remain in spite of adequate antipsychotic treatment.

During treatment, the patient describes her symptoms, and those that are most troublesome are targeted for attention. The goal is to change thought patterns in order to help the patient solve problems. This is sometimes called cognitive-restructuring. For example, a patient can be taught ways to ignore the voices she’s hearing.

Some of the specific elements of CBT may include:

Belief modification or validity testing: Challenging delusional thinking

Focusing/reattribution: Explaining the meaning of stressors behind auditory hallucinations

Normalizing psychotic experiences: Helping the patient see that her experiences are responses to stressful events

Cognitive rehearsal: Practicing how to better handle a future situation similar to one that was challenging in the past

Journal writing: Keeping notes to encourage insight, learning, and self-discovery

In essence, the CBT therapist challenges faulty thinking patterns (such as delusions and hallucinations) in an attempt to modify thoughts and behaviors. The reductions in positive symptoms seen with CBT continue after the course of treatment has been completed.

Unfortunately, CBT doesn’t seem to affect rates of relapse and rehospitalization. Some studies report that CBT helps with compliance in taking medication and, in fact, a specific variant of CBT emphasizes this particular behavioral goal. Another limitation to CBT is that it doesn’t seem to improve social functioning as well as supportive therapy. Also, because CBT requires a level of fairly organized thinking, it’s less useful for individuals who have cognitive deficits or who are still acutely psychotic. Nevertheless, for persons who have persistent psychotic symptoms even with antipsychotic medication, CBT offers another tested and proven method of getting symptomatic relief.

Getting Involved in Group Therapies

Group therapies can be led by professionals, consumers, family members, or some combination of one or more of them. They may include psychotherapy groups or various forms of self-help groups (also called mutual support or peer support groups) and family groups.

Group psychotherapy

Psychotherapy groups typically include 6 to 12 patients who meet with one or two therapists (who facilitate the discussion). From each other, patients learn how to cope with the illness and its symptoms. Group therapy provides a perfect forum to meet new people and learn how to get along with others.

For some, group therapy offers a number of advantages over individual therapy, including

Opportunities to meet people and improve social skills: This may be particularly beneficial to people who are extremely shy or have social anxiety.

Lower cost as compared to individual treatments.

Opportunities to provide and obtain peer support: People generally feel better about themselves when they’re able to help other people with their problems.

Group therapies are generally more appropriate after acute symptoms have subsided. They may be particularly difficult for people who still remain suspicious and paranoid.

Self-help groups

Self-help groups have a long history. An estimated 2 percent to 3 percent of the U.S. population is involved in some form of self-help group at any given time. These groups, often led by people with an illness or disorder (or by their family members), provide mutual support and practical help to others in similar circumstances. These groups are empowering for consumers because it allows them to see their peers as role models and they take advantage of what can be learned from people who have experienced an illness first-hand.

Self-help groups range from informal gatherings at someone’s kitchen table or a local coffee shop to more formal ones run by local organizations or national programs. Some of the more well-known self-help groups include Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD). Many of these groups are also very effective advocacy organizations because of their commitment, tenacity, and credibility to their causes.

Because a substantial portion of people with schizophrenia (estimated at 50 percent over the course of their lifetime) have co-occurring substance use disorders, AA programs can potentially play an important role in recovery. However, some of these programs, in an effort to help their members remain substance free, discourage members from taking their antipsychotic medications — which can be very risky for someone with schizophrenia. Your loved one should be cautious about joining AA if the leader of the group isn’t familiar with co-occurring disorders.

Some “double-trouble” groups are developed specifically for people with co-occurring disorders. Seek one of these out — your loved one can benefit from approaches that treat both disorders simultaneously. (See Chapter 6 for more information on co-occurring disorders.)

Research on self-help for people with schizophrenia suggests that these groups increase knowledge about the illness, enhance coping, improve vocational involvement, and provide realistic hope for the future. The groups can take many forms including consumer-operated mental-health programs run by consumers (such as case management, crisis, or peer support programs); more informal clubhouse models and drop-in centers; or peer support programs, to name just a few. Some of the characteristics these programs share in common include

Mentorship (opportunities to interact with positive role models) The sharing of coping strategies

Support of other people in similar circumstances Exchange of information and resources Enhanced self-esteem

Formation of friendships and socialization in low-stress situations Free or low-cost assistance

You can access a searchable database of self-help programs for a variety of disorders, including schizophrenia, at www.mentalhelp.net/selfhelp.

In the following sections, we cover some examples of self-help groups, but because these programs generally evolve at the local level, they tend to vary considerably from community to community, except in the case of several national programs Most self-help programs, in fact, are one-of-a-kind efforts sparked by recovering individuals who want to give back to their peers.

One example of a national program is Recovery, Inc. (www.recovery-inc. org), which was one of the first mental health self-help groups. It was founded in 1937 and is still alive and growing today. Recovery groups, of which there are now more than 700 chapters across the United States, bring together people with a variety of diagnosed and undiagnosed mental and emotional problems, including schizophrenia. Members meet regularly in their local communities (usually in a house of worship although there is no association with or discussion of religion) to learn techniques for handling the stress and the daily hassles people encounter in their lives. The approach is somewhat reminiscent of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) because it focuses on learning to change the thoughts and behaviors caused by psychiatric symptoms.

In a controlled study of Recovery, leaders and members reported fewer symptoms and fewer re-hospitalizations. Other studies of mental-health self-help groups have found improvement on psychological, interpersonal, and community adjustment measures; improved member self-confidence and self-esteem; fewer hospitalizations; more hopefulness about the future; and a greater sense of well-being.

Recovery meetings are intended to augment, not substitute for, psychiatric treatment.

Another example of a national model is the NAMI Peer-to-Peer program, which consists of nine two-hour courses that are taught by three trained mentors, individuals who are living with mental illnesses. To learn more about this program and find out whether courses are being given in your community, go to www.nami.org, and from the Find Support drop-down list, choose Consumer Support. Then click the Peer-to-Peer link. (Or just go to www.nami.org/template.cfm?section=Peer-to-Peer.)

Because schizophrenia is a brain disorder, society often uses the term patient to describe individuals with schizophrenia, as they would refer to anyone with a physical disorder. However, there’s considerable controversy in the field of mental health about language, because some of it can be very stigmatizing. So in this section, we use the word consumer or peer to describe the patient or recipient of services.

Grass-roots consumer-run programs include, but aren’t limited to, clubhouse models, drop-in centers, case-management programs, outreach programs, crisis services, employment and housing programs.

Clubhouse models

Psychosocial clubhouses, whose numbers are growing across the United States, provide peer support in an informal setting, and often provide help in locating other services. Participants, called members, often share responsibility with paid staff for the upkeep of the clubhouse. The clubhouses serve as training grounds to provide people with schizophrenia with skills they can use in the workplace and with the opportunity to forge social bonds. They also promote a sense of belonging as one may feel as a member of any other type of club. Some, but not all, provide residential care until a person can get permanently housed in the community.

The first such clubhouse, Fountain House (www.fountainhouse.org), opened in New York City in 1948. Today, the program has served more than 16,000 members. At Fountain House and many other clubhouses, members and staff learn to work together closely to enrich the environment for all their members. Thresholds (www.thresholds.org), in Chicago, is another well-known example of a clubhouse model.

The International Center for Clubhouse Development (www.iccd.org) has identified the defining characteristics of clubhouse programs:

An emphasis on working roles within the clubhouse

Opportunities for returning to competitive employment through transitional and independent employment programs

Recreational programming for evenings, weekends, and holidays Access to community services, benefits, and supports Outreach efforts when members are absent

Educational opportunities

Access to or provision of housing, which is viewed as a fundamental right of all members

Shared decision-making and governance of the clubhouse

The same Web site (www.iccd.org) provides a Clubhouse Directory under the About the ICCD tab.

One self-help approach that incorporates self-assessment and self-monitoring, and is now being used in many states, is the Wellness Recovery Action Program (WRAP) developed by Mary Ellen Copeland, PhD (www.mental healthrecovery.com). It is a self-management program that provides consumers with the tools they need to pursue their own wellness — teaching them, for example, what to do when they get stressed, how to maintain a healthy lifestyle, and how to identify early warning signs of relapse. WRAP is unique because its focus is on prevention and recovery as opposed to control of symptoms. Several large-scale studies of the program are now ongoing.

Drop-in centers

Funded by county or city mental-health authorities and various other private mental-health programs, drop-in groups are informal places for people with schizophrenia to meet. People are free to come and go as they please, and there generally aren’t any professionals involved in these operations. These programs sometimes appeal to consumers who are uncomfortable using traditional services.

Drop-in centers (as well as clubhouses) for homeless persons with serious mental illness are sometimes called safe havens. These programs are voluntary, welcoming, and try to avoid instituting unnecessary rules and requirements that would inadvertently discourage their use.

Volunteer programs

A number of programs make use of volunteers (from the community) or peers (recovering individuals) to provide supportive friendships, information, and assistance to people with serious mental illness, including those with schizophrenia. One of the best known of these programs is Compeer, Inc. (www.compeer.org), an international nonprofit organization that has more than 80 chapters serving more than 65,000 adults and children worldwide. Compeer programs offer one-on-one mentoring relationships, skill-building, and interim telephone support, all of which are intended as a complement to professional treatment.

To find out about the drop-in centers, clubhouses, or volunteer programs in your own community, contact your local city or county mental-health department. The appendix lists national consumer clearinghouses and technical assistance centers, funded by the federal government, that can help your loved one become involved in self-help programs.

Internet chat rooms and social media

With the growth of Internet chat rooms and new forms of social media, there are a multitude of opportunities for individuals with schizophrenia to talk with one another and participate as they choose. For example, there are more than 47,000 active members on the schizophrenia-focused discussion forums at www.schizophrenia.com. There are also groups on Facebook

(www.facebook.com) and MySpace (www.myspace.com) that may be interesting to people with schizophrenia. For example, the Facebook Mental Health Awareness group has more than 5,000 members, many of them consumers.

You can think of these sites as the virtual equivalent of a drop-in center. They can provide useful information and opportunities for social connections.

Several caveats for your loved one with regard to chatting or posting on forums on the Internet:

Be careful about revealing your identity or providing personal information online.

Make sure your loved one uses good judgment in selecting an appropriate e-mail address and doesn’t reveal his true name or identity.

Remember that these chat rooms are generally unsupervised, and people can get nasty in any chat room.

Be skeptical of advice if you know little about its source.

Online chats can complement face-to-face ones, but they shouldn’t be used as a substitute.

Be careful what you write on a Facebook or MySpace profile. You never know who’ll be reading it or whether it’ll come back to haunt you.

Chapter 10 provides additional caveats for evaluating information you find on the Internet.

Supporting the Whole Family

The use of family therapies in the treatment of schizophrenia began soon after World War II, when the prevailing theory for mental illness was that families of people with schizophrenia communicate in disturbed ways. (This was the blame-the-family era.) The goal of treatment was to repair the family system instead of focusing on the treatment of any one individual, even the person with schizophrenia.

Traditional family therapy focused on treating family pathology and dysfunction rather than providing families with the coping skills to help them support their relatives with schizophrenia. The most unfortunate consequence was that families were often viewed as part of the problem rather than people whose help and support could be fundamental to recovery (see Chapter 2). This often set up a schism between patients, their families, and doctors — and it made parents, especially, feel guilty and ashamed.

Now, family therapy is generally focused on helping families better cope by helping them understand schizophrenia, improving communication patterns among family members, and identifying solutions to help them and their loved one’s illness. Because of the strain having a relative with schizophrenia can place on a marriage, some families also benefit from couples therapy.

Not every person with schizophrenia has a family — and some patients refuse to have contact with their families or have alienated them by their behaviors. Support can come from many places, and for some individuals, friends, roommates, volunteer organizations, and religious organizations comprise “family.”

Family psychoeducation

Family psychoeducational groups educate families by giving them the information and skills they need to support their relatives’ recovery. The groups are led by mental-health professionals or trained group leaders and focus on improving patient rather than family outcomes. As the patient improves, the family’s quality of life typically improves as well.

The groups augment, but do not substitute for treatment, including medication.

Although the various models of family psychoeducation share many characteristics in common, they differ in several ways:

Participation of one family versus multiple families

Participation of family members exclusively versus family members and people with schizophrenia

Varying lengths of duration, ranging from ten weeks to more than five years

A focus on different illnesses and different phases of the illnesses

These programs have been shown to reduce relapse among consumers and to lower rates of hospitalization. In addition, they lead to increased participation in vocational programs and employment, improved family satisfaction, and decreased overall costs of care. To increase the number of these programs, efforts have been made to integrate them with ACT programs (see Chapter 5).

One of the largest psychoeducation programs for families, sponsored by NAMI, is called the Family-to-Family Educational Program. When patients leave hospitals, the most common scenario is for them to return to their families. This makes it essential for families or close friends to understand

everything they can about the illness and its treatment. Moreover, the families and/or friends need to accept the diagnosis and to have realistic expectations for treatment and recovery.

This free, 12-week course for family caregivers of people with severe mental illness is taught by trained family volunteers and provides information that can help them find the right resources and ask the right questions, ultimately leading to better care for their relative and less stress for the rest of the family. Every family member should take this course soon after a loved one has been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

We think it’s useful for as many members of a single family as possible to participate in family psychoeducational programs. This gives more people the opportunity to understand the disorder and sets the stage for spreading caregiving responsibilities among various family members.

Family support organizations

One of the most significant forces for advancing the treatment of schizophrenia has been the development of family support organizations, most notably the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

Family support groups generally serve three functions: Mutual support; information; and advocacy for improved mental-health services, increased funding for mental-health research, and improved public awareness to reduce stigma and discrimination.

Founded in 1979, the grassroots organization has affiliates in every state and in more than 1,100 local communities across the United States. NAMI state and local affiliates sponsor self-help groups for families who meet together to better understand mental illness and to better cope with the challenges the illness poses for themselves and their relative. Families who once felt isolated and helpless now realize that they aren’t alone and can depend on one another for support.

To find a NAMI affiliate in your community, go to www.nami.org and select the Find Support tab.

You may hear about programs offering art, music, drama, or other creative therapies for people with schizophrenia. There is scant empirical research supporting the effectiveness of these therapies for schizophrenia. But apart from their use as a treatment per se, the creative arts are life-affirming pursuits that bring pleasure and provide a way for people to relax, enjoy, and create. If your loved one demonstrates a proficiency or interest in the arts, encourage him!

Considering Cognitive Remediation

One of the most important recent advances in the field of psychosocial rehabilitation has been the emphasis on cognitive remediation (CR). The term cognition refers to the way a person thinks. Needless to say, the way a person thinks affects the way he approaches and performs many tasks in his daily life.

Neuropsychological testing has shown that the vast majority of people diagnosed with schizophrenia have a variety of cognitive impairments thought to be related to abnormal brain function, including

Difficulty sustaining attention

Impaired memory

Difficulties with verbal learning

Problems making decisions

Delays in the speed of thought processing

The severity of the disability can be marked; over 85 percent of individuals with schizophrenia score more poorly on cognitive functioning than 90 percent of healthy individuals.

Only recently have the severe consequences of these cognitive impairments — in preventing social and vocational recovery from schizophrenia, as well as interfering with the therapeutic benefits of other psychological inteventions — been recognized. As a result, treatment of cognitive impairment has become a therapeutic goal using biologic (see Chapter 8) and/or psychosocial approaches. Through a variety of techniques, CR — not to be confused with cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) — attempts to do one of the following:

Restore or improve thinking skills in either all or some deficit areas

Teach the person with schizophrenia ways of compensating for cognitive impairment

Modify the environment in which the person with schizophrenia functions to reduce her dependence on cognitive success in order to succeed.

Although attempts at cognitive rehabilitation began almost 40 years ago (in a more limited way), there is still no one commonly accepted or preferred way to carry out the training. Increasingly, repetitive skills training (learning through repeated use) is done on the computer, while other forms still use paper and pencil. Part of teaching consumers to compensate for their disabilities stresses organizing information instead of having to remember individual things. For example, CR encourages the use of lists and other aids placed in the environment to help the person with schizophrenia to remember what needs to be done and to keep organized.

Despite the fact that CR training varies from program to program, it’s clear that improvements in cognitive functioning do occur. Not enough studies have been conducted to determine how long the improvements last after training stops, or whether cognitive improvement also improves psychosocial functioning.

Combining other forms of psychiatric rehabilitation, such as social skills training and coaching, with specific cognitive remediation training seems to bring about greater changes in psychosocial functioning than CR alone. Rehabilitation programs often combine pure CR training along with other rehabilitation methods. Some of these combined programs include cognitive remediation therapy (CRT), neuropsychological educational approach to rehabilitation (NEAR), cognitive adaptation training (CAT), and cognitive enhancement therapy (CET). (You don’t need to know detailed information about these various programs, but it’s useful to be familiar with these names so when you hear the terms used, you can identify them as an approach to cognitive remediation.)

This is a time when many new methods are being tried to enhance cognitive functioning. We believe that when more widely standardized and tested psychosocial and biological (medication) approaches become available, combining them may lead to vast improvements in treatment. Better success may also be found by devising treatments that are more specific to a person’s individual impairments.

One of the biggest drawbacks to the use of CR today is the lack of programs and practitioners trained to provide CR. Some researchers are developing methods for families to be able to apply these methods on their own. For example, having family members remind the person with schizophrenia to compensate for memory problems by diligently writing things down and keeping lists or having someone who is highly distractible only undertake one task at a time (as opposed to multitasking).

The New York State Office of Mental Health has produced a handbook for friends and family members titled Dealing with Cognitive Dysfunction Associated with Psychiatric Disabilities. You can download for free at www. omh.state.ny.us/omhweb/cogdys_manual/CogDysHndbk.pdf.

Expanding Psychosocial Options

Consumer choice should be a major factor in selecting treatments. For choices to be informed, your loved one needs to know more about the risks and benefits of various treatments and be able to compare each of them in terms of their cost and effectiveness. This may be a tall order until your loved one reaches a certain point in the process of recovery.

Moreover, in the real world, most communities do not provide the full range of psychosocial, individual, group, self-help, and cognitive remediation treatments that are necessary to facilitate optimal treatment. The growth of the patient and family advocacy movement holds much hope for stimulating more interest and funding in these types of treatments.

The bottom line: Working together, consumers, families, and professionals need to:

Identify an individual’s particular strengths and deficits.

Find out about the availability of psychosocial rehabilitation practitioners and programs in the community.

Develop an individualized plan to minimize, remediate, or adapt to deficits created by the illness.

Become advocates to ensure that there are effective and self-affirming choices available to maintain and/or restore the dignity, self-worth, and productivity for people with schizophrenia.