In This Chapter

Understanding how medications work

Looking at commonly prescribed medications

Finding the right medication

Minimizing serious side effects

Enhancing medication compliance

One of the most important advances in the treatment of schizophrenia over the last half-century has been the discovery of antipsychotic medications — medications that reduce the troubling symptoms of schizophrenia and give people with schizophrenia the chance to live normal lives. Today, medication is considered the mainstay of schizophrenia treatment.

In this chapter, we look at the different types of medications available and their common side effects. We also cover the importance of compliance, the family’s role in helping ensure that their loved one stays on medications, and some of the difficulties you and your psychiatrist may experience in finding a medication that works. We also look at other medical therapies such as electroshock treatment and review the pros and cons of their use in conjunction with medication. (For information on psychosocial and other psychological treatments, turn to Chapter 9.)

Antipsychotic Medications

Antipsychotic medications have revolutionized the treatment of mental illness, including schizophrenia. In the following sections, we look at how and why they work, explain the difference between first- and second-generation drugs, and delve into treatment guidelines and what they mean for you. (If you’re interested in the history of these medications, check out the nearby sidebar, “The first antipsychotic medications,” for more information.)

The first antipsychotic medications

Before the discovery that certain medications could effectively reduce the symptoms of schizophrenia, most people with schizophrenia spent their time locked away from society in institutions. Various attempts were made to “treat” the disturbing symptoms of psychosis — hallucinations, delusions, suspiciousness, agitation, and disorganized thinking — but no tested treatments existed that were proven to be safe and effective.

There were some early efforts to use medications, along with other therapies, but the medications used at the time were mainly sedatives. And sedatives had to be given in such large doses that they were more likely to put people to sleep, cause confusion, or make people unable to react than they were to tame the symptoms associated with the disorder.

Then, in France, in 1952, a new medication, chlorpromazine (brand name: Thorazine) was developed for an entirely different purpose — to reduce the chance of cardiovascular shock during surgery. Serendipitously, when the medication was tried in agitated psychotic patients, doctors found that it calmed them without causing the sedation or drowsiness associated with sedatives. This was a watershed moment in the treatment of schizophrenia. It eventually led to the release of patients from institutions, a reduction in the number of psychiatric beds needed, and a new ability to treat people with schizophrenia in less restrictive settings.

Pharmaceutical companies were eager to make their own version of this new “tranquilizer,” clinicians were excited that they finally had a promising tool in their medicine bags, and researchers wanted to find out how the drug worked, because they knew it might offer clues about what was wrong with the brains of people with schizophrenia.

Understanding how medications Work on the brain

In order to understand how antipsychotics work on the brain, you need to understand how the brain is organized and how it works. The brain is an organ, and all organs of the body can be thought of as having a structure, a function, and a resultant action.

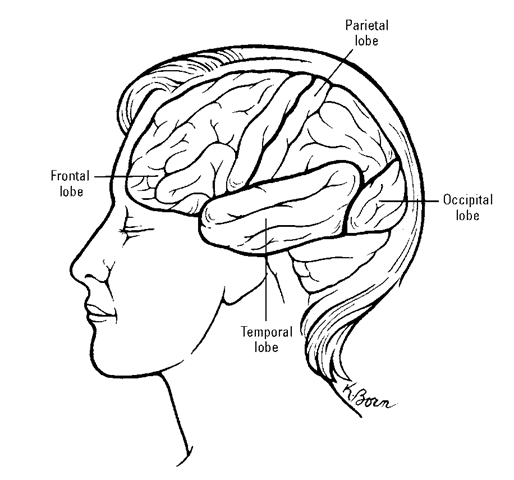

The structure of the brain (shown in Figure 8-1) is more complicated than most other organs. It has four lobes — the frontal lobe, the parietal lobe, the temporal lobe, and the occipital lobe. Within these structures, there is gray matter (made up of cells) and white matter (which is more like insulated electrical wires).

There are some 100 billion cells in the brain, although the actual number mainly decreases over the course of a person’s lifetime. Because the cells are very close to each other, they can communicate over the very small spaces between them; these spaces are called synapses. The way in which the cells communicate is both electrical and chemical. If a cell is stimulated, it produces a very small amount of a chemical, called a neurotransmitter, for a very short period of time (literally fractions of a second). This chemical stimulates the receptor on the next cell — if that cell has the matching neurotransmitter receptors. This chemical stimulation leads to a miniscule increase in electrical voltage inside the cell (brought about by opening of sodium ion channels) compared to the cell’s environment.

Figure 8-1:

The brain is divided into four lobes, making the brain one of the more complicated organs in the human body.

Based on how often the cells stimulate one another and their locations in the brain, they become organized into circuits. You can think of these circuits as “wires” that “connect” one part of the brain to another. Some of the circuits are specialized for the senses (such as sight and sound), some are specialized for thinking, and some are specialized for different moods. All these structures give rise to the function of the brain called the mind, which refers to all the conscious and automatic (unconscious) activities of thinking, feeling, sensing, and integrating (or organizing). The resultant action of the mind is behavior, what a person does (such as eating, sleeping, loving, and so on).

Through the use of precise electrical, chemical, and imaging techniques, scientists now know that medications that affect behavior work, to a large extent, by raising or lowering the amount of neurotransmitters (or the sensitivity of the transmitters) found in the different areas of the brain. In this way, a medication influences the important cell connections in the brain. If a neurotransmitter is involved with thinking, mood, or perception, it can affect the symptoms seen in schizophrenia.

Of course, the brain isn’t quite that simple. There are multiple neurotransmit-ters that can all influence each other and the cells they stimulate. Some of the major neurotransmitters are dopamine, glutamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

The earliest antipsychotic medications, which resulted in a tranquilizing effect, and all the similar antipsychotic medications that have since been developed influence the dopamine system, which is involved with the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. (See Chapter 3 for more on positive symptoms.)

Introducing first-generation medications

After the introduction of the first antipsychotic drug, chlorpromazine (brand name: Thorazine), in the early 1950s, other pharmaceutical companies marketed similar medications, which are now collectively referred to as first-generation antipsychotics. Table 8-1 identifies the most commonly prescribed first-generation antipsychotic medications.

First-generation antipsychotics are also sometimes called typical antipsychotics or conventional antipsychotics.

All the first-generation medications are equally effective (on average) in controlling the symptoms of schizophrenia. However, for reasons still unknown, some people seem to respond better to one antipsychotic medication than they do to another.

| Table 8-1 | Commonly Prescribed First-Generation |

| Antipsychotic Medications | |

| Generic Name | Brand Name |

| Chlorpromazine | Largactil, Thorazine |

| Fluphenazine | Permitil, Proloxin |

| Haloperidol | Haldol |

| Loxapine | Loxitane |

| Molindone | Moban |

| Perphenazine | Trilafon |

| Thioridazine | Mellaril |

| Thiothixene | Navane |

| Trifluoperazine | Stelazine |

Among people treated with these first-generation antipsychotic agents, about 35 percent do not have a good therapeutic response (defined as still having positive symptoms after trying two or more different medications for the recommended period of time). This condition is referred to as treatment resistance and, until about 1990 and the development of second-generation medications, few other proven alternatives were available to patients or their doctors.

Moving on to a second generation of meds

In 1990, clozapine (brand name: Clozaril), an antipsychotic medication marketed outside the United States, proved to be successful in a large clinical study that looked at treatment-resistant patients (see the preceding section). Remarkably, researchers found that about one out of three previously treatment-resistant patients significantly improved after taking clozapine.

However, clozapine had a serious drawback. In about 1 percent of people, it caused a marked and sudden decrease in white blood cells — a condition that can be fatal. So, in order to prevent this problem, anyone taking clozap-ine had to have weekly white blood cell counts before their prescriptions could be renewed. After some time, the blood draw could be reduced to every two weeks, and then monthly. As you can probably predict, many potential users of clozapine weren’t happy with the idea of having to get their blood drawn so often, just to stay on this medication.

After clozapine was marketed in the United States, other pharmaceutical companies rushed to develop medications that would be as effective as clozapine without the effect of decreasing the white blood cell count. In 1994, risperidone (brand name: Risperdal) was the first of a new group of antipsychotic medications to hit the market. Collectively, these new antipsy-chotics are referred to as second-generation antipsychotics. Table 8-2 lists the most commonly prescribed second-generation antipsychotic medications.

Second-generation antipsychotic medications are also sometimes called novel antipsychotics or atypical antipsychotics.

| Table 8-2 | Commonly Prescribed Second-Generation |

| Antipsychotic Medications | |

| Generic Name | Brand Name |

| Aripiprazole | Abilify |

| Clozapine | Clozaril |

| Olanzapine | Zyprexa |

| Paliperidone | Invega |

| Quetiapine | Seroquel |

| Risperidone | Risperdal, Consta |

| Ziprasidone | Geodon |

Unfortunately, other second-generation medications haven’t proven to be as effective as clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia, but they offer one important advantage over first-generation antipsychotics: They’re far less likely to cause adverse motor side effects (such as stiffness, tremors, or Parkinsonian-like abnormal involuntary movements).

In part, as a result of the aggressive marketing of these new medications, they’re now much more widely prescribed than first-generation antipsychotics in spite of their significantly higher costs.

Following treatment guidelines

Given the large number of antipsychotic medications available, it’s not surprising that a variety of professional associations and government agencies have published treatment guidelines (also called practice guidelines).

Being the first to receive new drugs

When new medications come to market (whether for schizophrenia or any other physical or mental disorder), it’s not necessarily a good idea to be first in line to try them. There are several reasons for this:

The proof for efficacy required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is only that a new medication is more effective than a placebo, not more effective than other medications already on the market. A placebo is what used to be called a sugar pill — it looks just like the real thing, but it doesn’t have any medication in it. So, in other words, the drug just has to be better than nothing.

Because new medications have, on average, only been given to about 3,000 people before a drug is on the market, it’s not uncommon for new and possibly dangerous side effects to be discovered only after the medication has been given to hundreds of thousands of people or for longer periods of time than when the drug was being studied.

The new medication almost always costs significantly more than the older medication, especially if a generic (non-brand-name) equivalent of the older medication exists.

If your loved one is not doing well and all the older medications have been tried and failed, you may welcome the opportunity to try a new medication. Be sure to ask your psychiatrist if the new medication represents a truly new approach or is more likely a “me, too” variation of an older product. “Me, too” drugs are generally more expensive (so they’re heavily promoted by pharmaceutical manufacturers) and tend to have more unknown risks because there’s less experience using them on large numbers of people.

Treatment guidelines provide recommendations, either based on research or expert consensus, to guide practitioners on how to assess and treat various psychiatric disorders. Although these guidelines differ in detail, they consistently recommend the following for antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia:

1. Start with a single antipsychotic medication (usually a second-generation medication), and evaluate the efficacy of that medication in four to six weeks.

2. If the first medication has not reduced the patient’s symptoms, try another antipsychotic medication — either first- or second-generation.

3. If there still is no good response to treatment, try clozapine (brand name: Clozaril).

Many guidelines are also written specifically for consumers and their families. The federal government maintains an online clearinghouse of these documents at the National Guideline Clearinghouse (www.guideline.gov). Reading through practice guidelines can’t make you a doctor, but it can inform you about various treatment decisions your loved one will be making with her doctor, and it can help you raise the right questions.

Starting on an Antipsychotic Medication

Medication decisions can be complicated and frustrating. Medications for schizophrenia may have to be changed, increased, decreased, and tinkered with to obtain optimal results. This situation can be frustrating for both patients and families, not to mention expensive, if new medications need to be bought before the old ones are used up. In this section, we look at the different factors that go into finding the right medication for each patient.

Recognizing the reason for trial and error

Deciding on the perfect drug for a particular patient isn’t an easy task. Although many studies have been conducted to find the “right drug for the right patient,” trial and error is still the only way to find the drug that works best with fewest side effects for a given individual. Usually, medication decisions are made on the basis of the potential side effects associated with different medications (for example, drowsiness, abnormal movements, drop in blood pressure, or weight gain), as well as the physical and mental state of the patient.

If the patient has ever been treated with an antipsychotic medication before, it helps the doctor to know what medications were used, whether they were successful in controlling symptoms, and whether they produced any uncomfortable side effects. This is where family and friends (or the person with schizophrenia) can be extremely helpful in working with the doctor to choose an antipsychotic medication.

Patients and their families should always keep a summary of the medication someone has taken, with the information listed in more detail in Chapter 14, so they have it available when it is needed.

Selecting the proper dose

Every FDA-approved medication has a recommended dose, which is the result of studies carried out before a drug goes on the market. However, with increased experience with the drug (both by your psychiatrist and others), the dosage found to be most beneficial may change even though the labeling does not.

For example, after risperidone (the first of the second-generation medications after clozapine) was marketed, it was found that the 8-milligram dose was higher than needed in most patients, and 4 to 6 milligrams rather than 8 to 16 milligrams became the dosage commonly used. Conversely, with other second-generation drugs such as ziprasidone (trade name, Geodon) and quetiapine (trade name, Seroquel) the initial doses recommended were found to be too low. The point is that sometimes the dose the psychiatrist prescribes may be different from what the package insert says is the recommended dose.

Finding a doctor who is familiar with the most up-to-date research on dosing, and who has experience gleaned from treating a large number or people with schizophrenia, is essential to receiving the correct dose of medication for your loved one, guided by what it says on the package insert.

The characteristics of the person receiving the medication are another important factor that influences dosing. For example, on average, heavier people will be prescribed higher doses than lighter people. Older people, children, and people with other health problems (heart, liver, or kidney problems, for example) will also receive lower doses.

Most pharmacies now provide printed information about the medications they’re dispensing. It’s a good idea to read this information, especially when a new medication is prescribed. The U.S. National Library of Medicine has a Web site (http://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov), where you can find consumer-friendly and trustworthy information about most medications; you can access it by entering either the generic or brand name of the drug. Many other sites provide information about drugs, but you need to assess the quality of the site (see Chapter 10).

Looking toward personalized medicine

A psychiatrist isn’t able to use a crystal ball to consistently select the right drug for a patient. Instead, psychiatrists have to resort to a regimen of trial and error. This is frustrating to patients who sometimes say they’re being used as human guinea pigs, and it’s also frustrating to doctors who want to get it right the first time. But it isn’t all that different from treatment for many other medical disorders (such as high blood pressure, arthritis, and so on).

In both general medicine and psychiatry, there’s reason to hope that this may soon change. As more knowledge is gained about the human genome, it appears that small differences in genes may lead to differences in response to different medications. As research proceeds, it may become possible to analyze a person’s individual genome and select the right drug from the get-go. This approach has been called personalized medicine.

Choosing the form of medication: Tablets, pills, liquids, or injections

The form and route of administration is another decision to be made with some medications. Many antipsychotic medications not only come in different oral forms, but also may be given by injection in slow-release and rapid-acting forms.

Swallowing tablets, pills, or liquids

Many medications are taken orally (by mouth), but there can be difficulties using oral medications. Some people have a hard time swallowing pills, and others avoid taking their medications by only pretending to swallow pills and later spitting them out (known as cheeking).

Although tablets and capsules are the most common oral forms for antipsy-chotic medications, there are also liquid preparations (useful for older adults and children), which can be added to some juices or squirted into the mouth. There are also quick-dissolving tablets, which when placed under the tongue, dissolve and are absorbed quickly; these are useful when people have difficulty swallowing or if they’re cheeking the medication.

Cheeking sometimes leads to a diagnosis of “treatment-resistant schizophrenia” when, in fact, the medication never had a chance to have a therapeutic effect. If cheeking is suspected (although it is sometimes very difficult to detect), blood samples can be taken to see if medication is, in fact, in the person’s system.

Injectable medications

Injection, usually into muscle (either the shoulder or buttocks) is another route of administration, but one that is not very popular in the United States. Not all first- or second-generation antipsychotics are available in injectable form, and there are two very different kinds of injectable medications that are given for different purposes: rapid-acting and slow-release (depot).

Rapid-acting forms

A rapid-acting form of injection (such as haloperidol, chlorpromazine, olanzapine, or zyprasidone) is usually given when a psychotic person is very agitated, aggressive, and uncooperative, either at a doctor’s office or in a clinic or hospital. Although no one likes injections, the purpose of doing this is to rapidly calm the patient so that he will be more cooperative in taking oral medication and more amenable to verbal or behavioral therapies.

These injections are not given as a punishment (as is sometime portrayed in movies or topics); instead, they should be thought of in the same way that an injection is given to someone who can’t breathe after a bee sting. It is a temporary measure to get a potentially dangerous or out-of-control situation under control, and assure the patient’s safety until he’s amenable to other treatment.

Slow-release forms

Another type of injectable antipsychotic medication is purposely designed as a slow-release form. (These are depot (extended-release) forms of some first- and second-generation antipsychotics that can be given by mouth.) The advantage of the injections is that they can be taken roughly once or twice a month, avoiding the daily medication hassles that often occur when people have schizophrenia (see the “Why people refuse to take or stop taking medication” section, later in this chapter).

Slow-release antipsychotic injections are known as depot medications in the medical community. You may hear members of your loved one’s medical team refer to the medication by this term.

One distinct advantage to slow-release injections is that if a person taking a slow-release antipsychotic starts showing more symptoms, a clinician can rule out noncompliance as the cause.

There are two slow-release first-generation antipsychotics available in the United States: haloperidol (brand name: Haldol) and fluphenazine (brand name: Prolixin). A slow-release form of the second-generation antipsychotic risperidone (brand name: Consta) is also available.

As of this writing, slow-release forms of olanzapine and a risperidone metabolite (paliperidone) are currently under review at the FDA for possible marketing.

Another advantage to slow-release injections is that if your loved one is not doing well, the oral form of the medication can be given (increasing the dose) without the person having to take an entirely new medication. Also, when someone moves from an inpatient to outpatient setting and it may take some time before the person gets appointment see her doctor, a long-acting medication can smooth the transition until she’s seen.

Deciding on dosing schedules

Some medications are taken only once a day, while others are taken every few hours. This is partly based on a medication’s pharmacology (how long its effect lasts), sometimes how large a dose needs to be given, and whether the treatment is just being started or has been taken for some time.

Certain antipsychotic medications have a long half-life (the time it takes for half the medication to leave the body) and even if they’re given only once a day, they can have an effect for a full 24 hours. Others have a shorter half-life and must be given two or more times a day to have their continued desired effect.

The measure half-life is used because it allows a comparison of the duration of effect (action) of similar medications and, therefore, how often during the day the medication has to be taken.

Obviously, if a person with schizophrenia objects to taking medication or is forgetful, or if no one is around to be sure he takes his medication, a medication with a longer half-life is better. If this situation applies to your loved one, you may want to raise the issue with his doctor.

Missing a single dose of a medication given only once a day is more significant than missing a single dose of a medication given several times a day. Making up for missed doses of medication by giving a larger amount at the next dose is usually not possible — in fact, doing so can actually cause an overdose. If your loved one misses a dose, continue with the next regular dose, and don’t try to make up for missed doses.

Very often, when medication is first started, it will be prescribed in smaller doses several times a day. Then, as blood levels build up and if there are no serious adverse effects (such as drowsiness, dizziness, fainting, and so on), the frequency of administration can be reduced. Usually the dose to be given once a day is increased and is preferably taken just before bedtime.

Tying the time of administration to a daily activity (especially waking up in the morning or before going to bed in the evening) is helpful as a reminder to take medication. It’s also helpful (and sometimes necessary) to take the medication at the same time(s) every day so blood levels never get too high or too low.

Some medications need to be taken with food in order to be fully absorbed; others need to be taken on an empty stomach. In addition, some medications need to be taken alone — taking them with other pills at the same time could reduce the effectiveness of the drugs. Be sure your loved one follows the doctor’s instructions on how to take medications. If you and your loved one aren’t sure, ask. When and how someone takes medication can make a big difference.

Managing Medication Adjustments

Taking antipsychotic medications often isn’t as straightforward for people with schizophrenia as it is for someone with a physical condition.

Medications may need to be changed, doses may need adjusting, and keeping a list of when to take multiple medications can be daunting for anyone, especially a patient struggling with mental-health issues.

There are some general rules for managing a regimen of antipsychotic medications, however, that apply in most cases. After your loved one starts on medication, it’s important that she does the following:

Take it as prescribed — the correct number of pills or capsules, the prescribed number of times per day, and with the prescribed time intervals in between. For example, a medicine taken twice a day usually should be taken 12 hours apart unless the doctor gives other directions (for example, take with meals).

Tell the psychiatrist how she’s been doing since the last time she was seen. Are her symptoms better, the same, or worse?

Tell the psychiatrist if she’s having any new or different symptoms or health problems. These may be related to the medication, and the doctor will want to make that determination.

Switching and adding medications

Even when your loved one follows doctor’s orders and does everything he’s supposed to do, the first medication he takes may not work right away. Let’s say he’s been taking a prescribed medication for four to six weeks and the symptoms that brought him to the doctor aren’t that much better or some others symptoms (possibly related to the medication) are giving him problems. It’s possible that the medication may not be the right one for him. In that case, your loved one, his doctor, and you have a variety of alternatives to choose from in terms of deciding on the next steps. These include

Raising or lowering the dose of the current medication Switching to another medication

Adding another medication from a different class of drugs (discussed later in this chapter)

Adding another medication from the same class of drugs

Good reasons for switching include:

When the symptoms for which the medicine was prescribed don’t improve or even get worse

When the medication is giving your loved one other symptoms (for example, drowsiness, sleeplessness, weight gain, or dizziness) that are making her life more difficult

When you or your loved one wants the doctor to consider whether another medication may be better for her (either a medication that’s more effective or one with fewer side effects)

When everyone has decided that you should make a switch and there’s a clear rationale for doing so, the question always arises of how long it’ll take and how you’ll know if it was a good idea. Some of the questions you’ll want to discuss with the doctor, if you all agree to switch medications, include the following:

Are you switching my loved one to a drug for the same indication as the one she was taking before, within the same class of drugs?

The term indication is used to identify a diagnosis or symptom that a drug is designed to treat. When pharmaceutical manufacturers go to the FDA, they provide evidence of the safety and effectiveness of a drug for a specific indication. When a drug is used for indications other than the one or ones for which it was approved, a practice that is legal, the use is considered off-label.

Will you be adding a new medication to her older one — but for the same indication?

How is the switch going to be made? Will it be abrupt or will there be a gradual reduction of the original medication as the new one is gradually increased?

Are there any side effects we should be aware of or report to you if they occur?

When and how (in person, by phone) should we talk again?

When medications are being changed, doctors will generally want to see patients more often or communicate with them by phone. If this isn’t arranged, be assertive and ask for an appointment if you have any concerns.

For a real-life story about a patient who switched medications several times before landing on the right combination, check out the “Brett’s story” sidebar in this chapter. Note: At one point when Brett was switching medications, his doctor recommended hospitalization so that he could be monitored more closely. It’s worth pointing out that most switching of medications only rarely requires a move to an inpatient setting. Various factors — medical, psychiatric, and logistical — are used to determine whether hospitalization is necessary.

Combining medications

People with schizophrenia (or any other chronic condition for that matter) very commonly take multiple medications. There are different reasons why multiple medications are prescribed, but when two medications from the same treatment class (in this situation, antipsychotics) are given together, this is called co-prescribing or polypharmacy. It’s important for patients and their families to understand the basics of polypharmacy.

The most common situations in which antipsychotic polypharmacy make sense include the following:

When schizophrenia is treatment-resistant, or doesn’t respond to the usual antipsychotic therapy

When some of the symptoms of schizophrenia respond to treatment but others do not

When there are significant side effects that make it impossible for the person to take a higher dose but where a higher dose is needed to control some symptoms of the disorder

Distinguishing between rational polypharmacy and irrational polypharmacy is important. Although polypharmacy has gotten a bad rap, if done for the right reasons and carried out in a logical way, it can be beneficial (refer to the nearby sidebar, “Brett’s story,” for an example). Logically enough, this is called rational polypharmacy.

An example of irrational polypharmacy would be a doctor concurrently starting a person with schizophrenia on two different antipsychotic medications at the same time, without trying one alone and with no prior history suggesting that this practice would be safe and beneficial to the person.

If a psychiatrist starts two medications at the same time, it is impossible to determine which one is causing problems or desired effects.

Another problem may occur if a second medication is added without fully stopping the first (called an incomplete taper). In this case, if the person improves, it may be believed that it is the “combination” that is working when, in fact, it may just be the second medication, and using one medication would be just as effective, less likely to cause side effects, and considerably less expensive!

Brett’s story

Brett’s treatment experience provides an example of how and why rational polypharmacy takes place. A 20-year-old honors student and standout athlete, Brett had never experienced any psychiatric symptoms before. During his junior year, he started hearing threatening voices and believed that he was being followed by aliens. He bought a gun to “protect himself.”

Brett became so fearful that he started placing phone calls to the police asking them for protection. His fraternity brothers were worried about him and got him to see the psychiatrist on campus, who diagnosed Brett with schizophreniform disorder (because his symptoms were of less than six months’ duration — see Chapter 4). Brett was hospitalized on the psychiatric ward and treated with a second-generation antipsychotic agent, olanzapine (brand name: Zyprexa).

Within two weeks, the voices stopped, and Brett no longer felt threatened by aliens. He was discharged from the hospital to outpatient care and continued to take his antipsychotic. He seemed to be doing well — except he gained about 25 pounds over a relatively short period of time, and he was having trouble concentrating on his studies.

As midterms approached, both Brett and his psychiatrist noticed that his symptoms were worsening. He couldn’t sleep, couldn’t study, and started feeling like someone was messing with his mind. The psychiatrist and Brett both thought that the stress of midterms was too great and, after a meeting among Brett, his parents, and the doctor, everyone agreed that the most prudent thing would be for Brett to take a temporary leave of absence from school and return home.

With the reduced stress at home, Brett felt better — his sleep improved, and he no longer had thoughts of anyone controlling his mind. However, his weight continued to increase and within a month, he gained another 15 pounds. He was also becoming more sluggish.

When Brett started to think about returning to school the next semester, he began to have doubts. His memory wasn’t as good as it used to be, and he was very self-conscious about his weight gain. He didn’t know how his fraternity brothers would react to him. His thoughts about aliens began to crop up again.

His psychiatrist didn’t want to increase his dosage, because of the substantial weight gain it had caused in the past. Instead, he suggested switching to another second-generation medicine that was less likely to exacerbate the problem. The dose of olanzapine was reduced as the new medication, ziprasidone (brand name: Geodon), was increased, until the olanzapine was stopped entirely. Brett’s weight dropped, but he became increasingly suspicious and reported that the voices were commanding him to protect the human race from danger.

The psychiatrist tried Brett on another second-generation antipsychotic, aripiprazole (brand name: Abilify). Although Brett did not gain weight on aripiprazole, the voices and delusions became so severe that the psychiatrist suggested another voluntary hospitalization to adjust the medication in a safe and secure setting where he could be observed medically. The psychiatrist gradually stopped the aripipra-zole and gradually restarted olanzapine but at a lower dose than before. When Brett started to improve, the psychiatrist didn’t raise his olanzapine dose any further (to avoid any additional weight gain), but he added a first-generation antipsychotic, haloperidol (brand name: Haldol) in a small dose because it’s known to be good for controlling hallucinations and delusions and doesn’t cause significant weight gain.

On this regimen of antipsychotic polypharmacy, Brett continued to improve so that he was well enough to return to school the following semester.

Coping with Common Side Effects

In order to be effective, a medication interacts with body systems to bring about therapeutic (desired) effects. Because medications rarely have an effect on just one single biological system in the body, along with the therapeutic effect comes other unwanted or side effects.

When these side effects are undesirable, they’re called adverse effects. Adverse effects can be mild or severe, and from a medical point of view they’re either not serious or serious (for example, requiring hospitalization or causing lasting disability). Regardless of whether a side effect is serious from a medical point of view, and regardless of the reason your loved one is taking a medication, no one likes to put up with annoying side effects — these side effects are often one of the reasons for noncompliance (see “Why people refuse to take or stop taking medication,” later in this chapter).

Some side effects only become a problem when the person has another physical or mental disorder. For example, a medication can cause urinary blockage in a man who has an enlarged prostate, but the same drug poses no problem in a woman or a young man with a normal prostate. Such side effects are more of an unknown when a drug is brand new and is less likely to have been used by a large number of people.

Side effects vary from medication to medication. The most common side effects are usually mild, not serious, and transient — but they can still be annoying enough to discourage people with schizophrenia from continuing to take the medication. Because every individual is biologically unique, people vary widely in the side effects that affect them and how bothersome they feel (regardless of whether the side effects are medically serious).

Even side effects that are not medically serious (for example, dry mouth, blurred vision, drowsiness, or drooling) can lead to noncompliance with medication regimens and should be taken seriously by everyone involved in a patient’s care.

When your doctor prescribes an antipsychotic medication, he should tell your loved one what side effects she may experience and which of them are serious enough that she should call or visit the doctor if they occur. Your loved one should tell the doctor about all new or worsening physical symptoms she’s experiencing because they could be medication-related.

Three kinds of side effects associated with antipsychotic medications are serious enough to have a doctor consider a change in treatment: movement disorders, weight gain, and metabolic problems. These side effects vary widely between first- and second-generation antipsychotics and among the different medications within these two different generations.

Antipsychotic medications are potent and effective treatments for schizophrenia. It may take some time to find the right drug(s) at the right dose(s). Careful vigilance, monitoring, and management to reduce side effects are essential to improve compliance and maximize medication effectiveness.

Movement disorders

Movement disorders occur as a side effect especially of first-generation antipsychotic medications — most often those that are called high-potency drugs (drugs that are very strong in small doses) or drugs that are given in high doses.

Among the most commonly used first-generation antipsychotics, haloperidol (brand name: Haldol) and fluphenazine (brand name: Prolixin) are two that often give rise to these side effects. The side effects are caused by the drugs interfering with the central nervous system structures in the brain that play a role in controlling motor functions.

Sometimes the side effects come on suddenly at the beginning of treatment and cause the patient to feel jittery and unable to stay still. This condition is called akathisia. Although it can be extremely frightening, it usually can be controlled rather quickly by reducing the dose or adding a counteracting medication. Other dramatic motor symptoms (such as back stiffness, the eyes rolling up in the head, or the neck turning to one side), called dystonias, can occur when medication is first started.

Although these symptoms usually aren’t life-threatening, they should be attended to immediately because they’re uncomfortable and frightening. No person should have to put up with these controllable side effects.

With continued treatment, some people develop a group of symptoms termed pseudoparkinsonian symptoms, because they look like, but aren’t really due to Parkinson’s disease. These symptoms include tremors (frequently of the fingers, but sometimes of the tongue and/or head); stiffness of the body, face, and limbs; and difficulty initiating movements. Again, dose reduction or the use of counteracting medications, called antiparkinsonian agents — such as benztropine (brand name: Cogentin) or diphenhydramine hydrochloride (brand name: Benadryl) — is usually very helpful.

After prolonged use of a medication, some patients may develop a neurologic syndrome called tardive dyskinesia (meaning, late occurring abnormal movements). If not diagnosed early, this condition can become chronic and occasionally is irreversible. With this syndrome, arms, legs, mouth, tongue, and even the body trunk may begin to move slowly and uncontrollably causing

abnormal involuntary movements. Usually the person with the disorder is not particularly troubled by it, but it’s very noticeable to others. Needless to say, this condition can be very stigmatizing to the person with the movements. The first time you notice any sign of these movements, report them immediately to your loved one’s clinician, who will likely prescribe another medication.

Although tardive dyskinesia tends to occur in people who have used first-generation medications, in some rare instances it has been diagnosed in people using second-generation medications. It is not clear whether this is due to their having used first-generation medications in the past. Elderly people, women, and people with mood symptoms are more likely to develop tardive dyskinesia.

Weight gain

Although not immediately recognized as a problem when second-generation antipsychotic medications first came into use, weight gain has turned out to be a significant adverse side effect, especially for some of these medications. In particular, clozapine (brand name: Clozaril) and olanzapine (brand name: Zyprexa) have been associated with rapid and profound weight gain in many patients taking these medications.

Before weight gain was recognized as a problem, patients weren’t advised to monitor their diets or encouraged to exercise. Doctors also made no attempt to switch drugs or avoid other medications that also may cause weight gain, compounding the problem. Many patients gained significant amounts of weight on these medications, which put them at risk for cardiac and other physical problems.

Today if weight gain starts to be a problem and is recognized, patients can be tried on other second-generation antipsychotic drugs that are less likely to cause weight gain (such as ziprasidone or aripiprazole). If a medication is working particularly well and your doctor doesn’t want to change medications, she may prescribe medication to counteract weight gain instead of changing medications.

When families aren’t aware of the properties of these medications, they simply blame the weight gain on the person’s eating habits (for example, too much junk food) or lack of exercise, which creates conflicts between patients and families. Watching a relative become free of positive symptoms but gain so much weight that his physical health and appearance are severely compromised is very painful. Worsening this problem, negative symptoms can interfere with a person’s motivation to exercise or take care of himself.

You may want to suggest to your loved one that he get help for what’s a very difficult problem to solve on his own. Suggest that your loved one discuss his weight problem openly with his psychiatrist and internist, and perhaps a nutritionist. By adjusting your loved one’s medications, they may be able to make weight loss easier (although there is no magic bullet for weight loss, and he’ll still need to watch his diet and get regular exercise). You may want to suggest that the person join a health club or take part in an exercise program at a mental-health program.

Try to be as supportive as possible in a situation that’s largely not under your loved one’s control. Don’t inadvertently sabotage your loved one’s efforts at treating his illness or controlling his weight.

Metabolic problems

Along with the problem of weight gain, doctors noticed that some people on antipsychotic medications developed elevated blood sugar, which led to a diagnosis of Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Occasionally, this came on suddenly, and the patients had such severe problems with sugar metabolism that they had to be hospitalized due to a life-threatening metabolic situation.

Much more frequent has been the need to medically treat the diabetes with either oral antidiabetic drugs or with insulin, and to develop strategies to manage diet and exercise. In fact, wellness and fitness approaches have become much more frequent in the care of people with long-standing schizophrenia. These programs are offered by many psychosocial rehabilitation programs in the community.

It’s vital for doctors and families to encourage regular health checkups for people with schizophrenia. Be sure that the physician caring for a person with the disorder is aware of the potential physical health problems associated with the use of these medications. Be sure that your loved one follows up with periodic laboratory tests as recommended by her psychiatrist or other physician.

Although they’re hard to find, some physicians specialize in the medical care of people with psychiatric illnesses. You might ask your loved one’s psychiatrist to recommend an internist who is experienced working with people with schizophrenia.

Frequently associated with the sugar metabolism problem has been another dietary metabolic problem, namely lipid (fat) metabolism of the type seen with coronary artery disease. When elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels occur, they can be treated with statin drugs (such as Lipitor) as well as with diet and exercise.

Other side effects

Other medication-induced problems can also occur. Most first-generation and some second-generation antipsychotic agents (including risperidone) cause a rise in the hormone prolactin. In some males, high prolactin levels can cause enlarged breasts (which can prove quite embarrassing, especially in adolescents and young adults) and may also be implicated in irregular or missed periods in females. Small hormone-producing but benign (not cancerous) pituitary tumors have also been associated with first-generation antipsychotic medications.

Finally, a life-threatening (but fortunately, very rare) side effect known as neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), characterized by high fever, confusion and hypotension (low blood pressure), is a real medical emergency that must be treated immediately — otherwise, the patient may die. Patients and their families should be alerted to the remote possibility of NMS by their doctors and immediately call the psychiatrist (who may well suggest that the person with schizophrenia go to an emergency room right away).

Other Classes of Medications Used to Treat Symptoms

Although schizophrenia is most commonly associated with symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized thinking, symptoms such as depression, anxiety, or sleep disorders also can occur during the course of this chronic illness.

Different classes of drugs are used as additional treatments: Mood symptoms often require antidepressants or mood stabilizers to control them, while problems with anxiety, nervousness, and sleep problems can be treated (usually for short periods of time) with anti-anxiety agents or sleeping pills (also called hypnotics).

Negative symptoms and cognitive impairments are two other categories of symptoms that need to be addressed in treatment, but because there aren’t any FDA-approved medications for their treatment, we discuss them in Chapter 10, on research.

Antidepressants

Symptoms of depression (such as feeling blue or hopeless, lack of interest in people or things, changes in appetite or sleeping patterns) may occur during

the course of schizophrenia, but they’re not the primary or most prominent symptoms. Nonetheless, they can be quite disabling to the person with the disorder and discouraging to loved ones and caregivers as well.

That’s why it’s fairly common for doctors to prescribe antidepressant medications (such as Elavil or Zoloft) along with antipsychotics to control the symptoms of depression. Care must be taken when antidepressants are used — the uplifting effects of these drugs can worsen the positive symptoms of schizophrenia, particularly when the antidepressant is initially prescribed or when the dose is raised.

Suicide rates are markedly elevated in people with schizophrenia so identifying and treating depression can be life-saving. Although the person in the throes of depression may not believe it, depression is a treatable illness.

Knowing just how much antidepressant is needed can be a bit of a balancing act. Providing good feedback to the physician about how your loved one is dong (for example, sleeping better or sleeping worse; becoming more or less aggressive; becoming more or less interested in news, TV, and the world around her) can really help the doctor adjust medication appropriately. Depression at times can become so severe that a person feels suicidal. (See Chapter 14 for more about the risk of suicide in schizophrenia.)

Sometimes when positive symptoms are treated and people with schizophrenia have a better grip on reality, the awareness of the very real setbacks and losses they have encountered as a result of their illness can lead to depression. Whenever someone feels depressed, it’s important that he tell his clinician and family. However, it’s also important for family members to be aware of the possibility of depression, watch for its symptoms, and if it is severe, encourage their loved one to tell his doctor.

Mood stabilizers

For some people with schizophrenia, mood symptoms of elation (excessive energy and activity) may occur along with, or independent of, symptoms of depression. The elation may become edgy (sarcastic and aggressive) and border on hypomania (which is characterized by not needing sleep, as well as rapid and continuous talking).

If these symptoms occur or cycle with depression, medication known as mood stabilizers (medications that are used to even out moods) can be helpful. One of the most widely used mood stabilizers is lithium. Although there is some question about whether lithium relieves depression, it is a virtual godsend in preventing, shortening, and controlling elated or manic behavior.

The dosage of lithium must be monitored carefully (by laboratory testing of lithium levels in the blood), because there is a very small difference between an effective therapeutic level and one that is toxic. When the levels are adjusted, however, the medication can be taken over prolonged periods of time with only occasional blood monitoring unless the person develops diarrhea, vomiting, or profuse sweating and fluid loss or dehydration. Under these circumstances, lithium administration must be suspended and the dosage adjusted again.

Besides lithium, other mood stabilizers that are regularly used as anticonvul-sant drugs are also in common use. These medications are, for the most part, being used off label (meaning, they haven’t been approved for the treatment of schizophrenia — although several have been approved for the treatment of bipolar disorder). The most common mood stabilizers in this class are valproate (brand name: Depakote) and lamotrigine (brand name: Lamictil). These medications are not without their own side effects (such as weight gain or a severe and life-threatening rash called Stevens-Johnson syndrome), and they should be used only when there is an established need and when prescribed by experienced clinicians.

Because of its propensity for weight gain, some patients call Depakote “Depa-bloat.” The same cautions we provide earlier pertaining to excessive weight gain need to be considered when using this medication as well.

Antianxiety medications

It’s not unusual for people with schizophrenia to feel nervous, jittery, or tense. Generally, antipsychotic medications reduce or take the edge off these symptoms. In fact, some antipsychotic drugs are used for the treatment of anxiety (without schizophrenia). Sometimes however, something more specific or potent may need to be used to address these uncomfortable symptoms.

The most common class of antianxiety agents are the benzodiazepines (such as Librium, Valium, Xanax, and Clonapin), which are prescribed medications. However, these medications have a dependence/addiction potential and should be used only for short periods of time with good monitoring.

This same class of drugs contains some compounds that are sold and used as sleeping pills. Frequently anxiety can be accompanied by the inability to fall asleep and, thus, antianxiety benzodiazepines may be given at night to help induce sleep. There are, of course, other hypnotic medications (for example, Ambien or Lunesta), but it’s better to avoid using too many medications, especially when they may produce physical or mental dependence.

Anxiety may sometimes be experienced as a result of akathisia (feelings of inner restless) that are a side effect of certain antipsychotic medications (especially first-generation ones). The proper treatment is either to reduce the dose of antipsychotic medication or to switch to another, perhaps second-generation, antipsychotic agent. Remember: Using an antianxiety medication instead of removing the cause of the anxiety is not the best course of action — it’s better to figure out the root cause of the anxiety and solve that problem rather than relying on medications.

In many people with schizophrenia, one of the first symptoms of worsening or relapse is difficulty sleeping. If this is the case, increasing the dose of the antipsychotic agent is generally preferable to taking a sleep medication. Don’t hesitate to ask a doctor what he thinks is the cause of your loved one’s sleeplessness before asking for a prescription for a sleep medication.

Adhering to Medications

Studies show that most people don’t take prescribed medication properly. Many families are frustrated by relatives who are unwilling to take medication at all or who are unwilling or unable to take it consistently. Others find that their loved ones go off medication as soon as it begins working and they start to feel better. This doesn’t only hold true for psychiatric medications. Many other chronic physical illnesses, such as diabetes or hypertension, demand long-term compliance (sticking to a prescribed treatment regimen), and people aren’t always willing to comply with a doctor’s orders over the long haul.

Large studies of compliance to all types of medications prove that people are less likely to recognize the importance of taking medications for chronic conditions like Type 2 diabetes (where compliance rates are estimated at only 20 percent) or high cholesterol than they are for disorders that have noticeable physical symptoms. Families and doctors need to reinforce the importance of taking these medications regularly.

Taking any medication can be a catch-22; almost every medication that works has potentially undesirable side effects. The worse the side effects, the less likely it is that a person will take the medication prescribed as ordered. But when schizophrenia is inadequately or inappropriately treated, the effects on a person’s quality of life and that of the people around him can be devastating. The person is more likely to be hospitalized, abuse alcohol and/or drugs, be jailed, or become homeless. With no proper treatment in sight, families feel a sense of hopelessness and despair.

Because medications are the most important tool in the psychiatrist’s arsenal, doctors need to maintain an open dialogue with reluctant patients and their families to fully explain the risks and benefits of these medications. Every effort needs to be made to find a medication that’s not only effective, but acceptable to the patient and her family.

Why people refuse to take or stop taking medication

Although the reasons why people refuse to take or stop taking antibiotics or cholesterol-lowering medications are similar to the reasons why they don’t adhere to antipsychotic drug regimens, psychiatric symptoms add some additional barriers, including uncomfortable side effects, lack of insight into the illness, disorganized thinking, the high costs of medication, and attitudes toward psychiatric medications. We cover all of these in the following sections.

Uncomfortable side effects

Antipsychotic drugs have many side effects, ranging from annoying to potentially serious health concerns. Although the symptoms vary from drug to drug, many patients report that antipsychotic drugs make them feel drowsy, stiff (sometimes patients report feeling like zombies), confused, unclear, or not like themselves. Sometimes symptoms of the illness become confused with side effects of the medication.

Many times, these side effects become more tolerable over time, but often they’re uncomfortable enough that they cause a person with schizophrenia to stop taking her medication before the side effects subside.

Side effects (described in the “Coping with Common Side Effects” section, earlier in this chapter) must be viewed as valid concerns that need to be addressed to see how they can be prevented or avoided.

Lack of insight into the illness

When schizophrenia first appears, you may be baffled and frustrated by the fact that your loved one doesn’t seem to realize that anything is wrong with him. One study estimated that approximately half of all individuals with schizophrenia and 40 percent of those with bipolar disorder don’t recognize their symptoms. The degree of insight a person has can vary over the course of the illness but, in most cases, it is most impaired when the disease first appears.

Why insight is so compromised remains an area of controversy. It could involve some denial, with the patient unwilling to admit that she’s sick. But more likely it’s a deficit in cognition (thinking) in the brain. Regardless of the cause, lack of insight often becomes a source of misunderstanding and conflict between patients and their relatives. The relatives just wish they could shake the person and make her understand. The patient feels like her relative is trying to control her behavior (which is true, to some degree, but for good reason).

One family member told us a story about her husband who had been ill during most of their marriage but refused to take medication for more than two decades. He never accepted his diagnosis, even though he was becoming progressively more psychotic and dysfunctional — and the couple was at the brink of financial ruin. He would substitute aspirin for his prescribed medication (saying that all pills looked the same) and often refused to take medication at all. Only after multiple hospitalizations, including a ten-month inpatient stay, did he come to terms with his illness and his need for medication.

Disorganized thinking

When thinking is disorganized, understanding or following any rules or regimens — including how and when to take a complex mix of medications — is difficult. Drug regimens can be extremely complicated for people with schizophrenia, who often need to take multiple pills to effectively control different symptoms. Not only does it require remembering which pills to take at which times, with or without food, but also which prescription needs to be refilled when.

Written aids like schedule charts or graphs, or physical aids such as pill boxes, which separate pills not only by day of the week but also by time of day can be very helpful to those struggling with disordered thinking. Help from others in keeping scheduling straight may also be necessary.

High costs of prescription meds

The costs of prescription medication can be financially crushing especially for individuals who live on fixed or limited incomes, and those whose health insurance doesn’t cover the cost of medications. According to the Kaiser Health Foundation, the wholesale prices for the 50 most often prescribed brand-name medications increased by nearly 8 percent in 2007. Many of the second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics that psychiatrists are likely to prescribe either are still under patent or are toward the end of their patents, which means they will soon become available in generic form. The pharmaceutical industry tries to encourage patients to switch to similar, but newer, “me-too” drugs that are higher priced.

If patients are enrolled in Medicaid or Medicare, they may have outpatient prescription drug coverage, but state policies differ regarding copayments, the number of prescriptions that can be filled, and the specific drugs that are covered.

Some patients try to save money by taking pills less often than prescribed, or by dividing prescriptions in half to make them last longer. This can make treatment seem ineffective and can lead to the doctor “tinkering” with medications, when in reality the patient isn’t taking the dose prescribed. Chapter 7 provides information about some of the prescription assistance programs that help provide support for people on limited incomes.

Attitudes toward psychiatric medications

There’s still a great deal of stigma attached to taking medications for a mental disorder as compared to taking them for physical problems. Sometimes, patients see taking medication as a constant reminder that they have an illness they don’t want to have, so they either won’t start medications or suddenly stop. Other times, people go off their medications as soon as they feel better, not realizing that stopping the medication will result in relapse. Some patients and their families believe that the more medication you take, the sicker it means you are — which is simply not true.

It’s a common tendency for patients to feel that they want to try going off medication to see if everything will be all right. Usually people are feeling good because the medication is working. Many times, doctors want to try to reduce dosages or eliminate one or another medication, and this may be possible, but it needs to be done under the close supervision of the prescribing physician to prevent relapse.

Another common complaint made by patients and families, and mentioned earlier in this chapter, is that they’re being used as “guinea pigs” because their doctors have to depend on trial and error. To some extent, this is true — but patients (and their families) need to understand that medication regimens must be individualized for the person, because what works for one person may not work for another and what once worked for your loved one may not work for him now. This is often hard to accept, because it makes it evident the very real limitations of what the medical profession knows and doesn’t know about schizophrenia and its treatment.

What you can do to ensure your loved one takes his medications

As much as possible, try to get your loved to take her medications at the same time each day. Here are some ways she can remember to do that:

Associate taking medication with a daily routine (brushing her teeth or eating breakfast, for example) or a visual cue (for example, a kitchen counter).

Use a divided pill container to help your loved one keep track of her medicines that have already been taken and those that haven’t.

Make sure that your loved one’s doctor explains — and you and your loved one understand — the reason she’s taking each medication and the risks of not taking them. If your loved one knows why she’s taking the medication, she may be more likely to stay on track.

Ask your loved one’s psychiatrist to minimize the number of daily doses whenever practical (remembering that short-acting drugs may require more doses).

Don’t let running out of pills serve as an excuse for not taking them. Remind your loved one not to wait until the last day to refill a prescription; retail pharmacies aren’t required to keep every type of medication in stock, so you want to make sure your loved one renews her prescriptions about a week before they’ll run out. If she uses a mail-order pharmacy, make allowances for the time it will take for the medications to get to her door.

People often stop taking their medications because they are experiencing annoying side effects. Remind your loved one to report any uncomfortable side effects to her doctor before she stops. A change in dose, change in the medication, or change in the time they are taken may remedy the problem.

When Medication Doesn’t Seem to Work

There are times when the best attempts at finding a workable medication or combination of medications fails. Even after trying several antipsychotic medications at different doses, in different combinations, and with various other medications alongside — and with use of non-medication treatments (such as psychotherapy, peer support, psychosocial rehabilitation, and so on) — an individual’s symptoms may remain severe and unresponsive to treatment. Even after obtaining a second opinion (see Chapter 5), you and the doctor may come to the conclusion that there are no other options available at the moment.

In situations like these (which, fortunately, are relatively infrequent), if a person is in continued psychic and possibly physical distress either electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) or other physical treatments (see Chapter 10) may be worth trying.

Few treatments have been so misunderstood and vilified as electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), commonly referred to as electroshock therapy. Sometimes ECT is even confused with the controversial approaches that use powerful

shocks to modify behavior — they have nothing in common except that they both use electrical energy. Although certainly not a first-line treatment for schizophrenia, several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of ECT when used in difficult cases — and even when used as a long-term follow-up treatment for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

ECT is given in a humane and precisely measured way, using general anesthesia and muscle relaxants to avert any pain or physical fractures, which could be caused by the seizures that are induced by passing an electrical current through the brain. The team (usually comprised of an anesthesiologist, psychiatrist, and nursing personnel) that administers ECT should be carefully trained and experienced, and should use one of the electronic devices that can deliver very programmed amounts and types of electrical current waves. Under these circumstances, ECT is generally safe — although, like all physical treatments, it can have side effects. The most common side effect of ECT is temporary memory loss, which infrequently can be more prolonged.

ECT can be a life-saving treatment for patients with agitation associated with schizophrenia that can’t be controlled (called intractable agitation) or with treatment-resistant catatonic schizophrenia (see Chapter 4). When a person with schizophrenia hasn’t responded to other treatments, ECT can also make the difference between a person being hospitalized indefinitely or becoming an outpatient.

Before rejecting ECT or a suggested therapy, you and your loved one should talk to the doctor about the ins and outs of the procedure. Don’t rely on negative media portrayals such as those you may have seen in One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest as your source of information. Those movies also show insulin shock treatment, a procedure that is no longer used.

Although no one can say for sure precisely how or why ECT works (which is also true for many other treatments in medicine), there is clear clinical evidence that is it both safe and effective when given under proper medical supervision under the proper circumstances.

Looking back at previous medical therapies

In the past, many treatments that seem completely senseless or terribly inhumane in hindsight were tried in an effort to control the symptoms of schizophrenia. These treatments ranged from uncomfortable but harmless treatments (such as cold baths) to potentially medically dangerous treatments (such as

injections of insulin to induce low blood sugar and coma), as well as permanently damaging treatments (such as lobotomies). There is little evidence that any of these now-abandoned treatments were generally effective, especially in treatment-resistant cases.