Ceramics

The technique of producing objects made of fired clay, which in the European Middle Ages and Renaissance could range from the purely practical (e.g. roof tiles) through decorative floor tiles and vessels to high art (e.g. the enameled terracotta sculptures of Luca della robbia). At the merely functional level, pottery was practiced wherever suitable clay could be found not too far from a source of water and sufficient wood for fuel; local production had the advantage of minimizing the expense and hazards of transporting the heavy but fragile finished products. For major building projects, such as palaces or monasteries, kilns would be set up on site to make the necessary tiles. Stamps were used to make the patterns on two-color floor tiles, with a (usually) white slip poured into the impressed areas of the design before firing.

The major Renaissance development in the field of decorative ceramics was the type of tin-glazed pottery known as majolica. In the 15th century Valencia was a major exporter of majolica wares. Elaborately decorated and colorful Italian majolica was exported all over Europe from such centers as the Montelupo potteries in Tuscany or Faenza, near Bologna. ("Faience," the generic name by which such tin-glazed wares were known in most of northern Europe, derives from the latter.) The technique was imported into England in 1567 by potters from Antwerp. An indigenous German type of pottery was salt-glazed stoneware (German: Steinzeug), manufactured in the Rhineland from the 12th century onward; clay and a fusible stone were fired at a high enough temperature to vitrify the stone to make nonporous vessels.

Cereta, Laura

(1469-1499) Italian humanist, feminist, and scholar

From an aristocratic family in Brescia, she was educated at home by her father, who encouraged her interest in mathematics and taught her Latin and Greek. She also engaged in self-education, taking up astronomy, philosophy, theology, and the study of literature, her great favorite being petrarch. She was widowed within 18 months of being married off when she was 15, by which time she had begun corresponding in Latin with humanist scholars in Brescia and the Veneto, as well as with Casandra fedele. Her scholarly activities attracted attention, and criticism, in Brescia, to which she responded with passion, defending the right of women to be educated. In 1488 she brought out a volume of her letters, but such was the hostility to female scholarship that she published no more, although she resisted the exhortations of her male critics to retire, as they deemed fit, to the contemplative life of a nunnery.

Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de

(1547-1616) Spanish novelist, poet, and dramatist

One of the large family of a poor and unsuccessful doctor at Alcala de Henares, Cervantes had little formal education apart from a period at a Madrid school run by a follower of Erasmus. In 1569 he went to Italy, joined the Spanish army there, and was wounded in the naval battle of Lepanto (1571), losing the use of his left hand. After completing military service, he boarded a ship for Spain in 1575 with a written commendation by Don John of Austria, but was seized by Algerian pirates and held captive by the Turks in Algiers for five years while he vainly tried to raise the necessary ransom. When it was finally paid by the Trinitarian Friars in 1580 and he returned to Spain, he hoped for some reward for past services but was ignored. His marriage in 1584 was an unhappy one and his first attempt to earn a living by writing, the pastoral romance La Galatea (1585), was hardly successful. He had a somewhat better return on his early plays for the Madrid theater, but his circumstances did not improve. In 1587 he was forced to leave Madrid to work in Andalusia as a tax collector. He was imprisoned two or perhaps three times for debt or trouble with his bookkeeping and spent a number of years living in Seville. After Part I of his great masterpiece don quixote appeared (1605), he spent the final and most productive years of his life in Madrid. Despite his fame and the immense success of Don Quixote, his grave in Madrid was unmarked.

Though Cervantes wrote verse and included many poetic passages in his prose works, he acknowledged that he had little talent for it. Early lack of success in the theater did not discourage him from making a second attempt, and he collected his later plays in Ocho comedias y ocho entremeses (1615). The entremeses, one-act prose farces, proved especially congenial to his gift for comic dialogue and social satire. The 12 short stories collected in Novelas ejemplares (Exemplary Novels; 1613) contain his most interesting work after Don Quixote. A long romance, Persiles y Sigismunda, was published posthumously (1617) and translated into English two years later.

Cesalpino, Andrea

(1519-1603) Italian physician and botanist

Cesalpino was born at Arezzo, studied at Pisa, and in 1555 succeeded Luca Ghini as director of the Pisan botanic garden. He moved to the Sapienza in Rome in 1592. De plantis libri XVI (1583) starts with botanical principles; following Aristotle’s division of plants into trees, shrubs, shrubby herbs, and herbs, Cesalpino’s pioneering classification concentrated on fruits and seeds, neglecting broader affinities. The greater part of his book contains descriptions of about 1500 plants, but with less advice on their uses than the herbalists provided.

Cesarini, Julian

(1398-1444) Italian churchman Cesarini was born in Rome and studied at Perugia and Padua, where he was a friend of nicholas of cusa. He occupied several posts in the papal Curia, and in 1425 was sent on a diplomatic mission to John, Duke of Bedford, regent of France for Henry VI. In 1426 he was made a cardinal and transferred to England, where he met Cardinal Beaufort and the humanists patronized by Duke Humfrey of Gloucester. In 1431 he was appointed papal legate in Bohemia, Germany, Hungary, and Poland, to direct a crusade against the hussites. He presided at the Council of basle, which opposed the policy of Pope Eugenius IV and attempted to limit the papal power. Later, at the Council of Ferrara, which transferred to Florence, he negotiated a settlement with the Greek Orthodox Church. In 1442 he went to Hungary to preach a crusade against the Turks, and was killed during the flight after the defeat of the Christian forces at Varna, Bulgaria.

Chain of being

The doctrine that all natural entities, whether mineral, vegetable, or animal, are linked in a single, continuous, unbroken sequence. It originated with Plato and began to lose its appeal only with the geological revolution of the late 18th century. The animal and vegetable kingdoms, it was claimed, are so connected that it was impossible to distinguish between the highest plant and the lowest animal—and so on throughout all parts of the natural world. Considered hierarchically the chain (or ladder) of being joined the lowest natural form in a continuous sequence ultimately to God himself. Further, according to the related principle of plenitude, the chain extended throughout the whole of nature. This latter view was apparently dramatically confirmed during the late Renaissance period by observations made through the newly invented microscope. Every green leaf was shown to be swarming with animal life, while the animals themselves were also shown to be similarly inhabited.

Chambers of rhetoric

Amateur literary societies in France and, more significantly, the Netherlands, active from about 1400. The rhetoriqueurs (French) or rederijkers (Dutch) were mainly middle-class townspeople who formed associations similar to guilds in order to promote their love of poetry and drama. They were mostly encouraged by the civic authorities and they reciprocated by organizing public celebrations, but the religious upheavals of the 16th century caused many of the chambers to fall under suspicion of heresy, and by 1600 their heyday was generally over.

Like the meistergesang guilds in Germany, the chambers of rhetoric were not usually innovative in their literary enterprises or particularly quick to respond to Renaissance ideas; they were however associated with the rise of secular drama in northern Europe, and the Dutch Elckerlijk (c. 1495) is probably the source for the English morality play Everyman. Significant Dutch writers associated with the rederijker tradition include: Cornelis Ever-aert (c. 1480-1556), playwright and member of De Drie Santinnen at Bruges; Matthijs de Castelein (1485-1550), author of the first Dutch treatise on poetry, De Const van Rhetoriken (1548); Colijn van Rijssele, the 15th-century author of the bourgeois drama cycle De Spiegel der Minnen (The Mirror of Love); Anna bijns, a schoolmistress at Antwerp; Dirck coornheert; and Henrick spiegel. The fanciful names adopted by the chambers were expressed in mottoes and emblems: they included De Egelantier and ‘t Wit Lavendel at Amsterdam, Het Bloemken Jesse at Mid-delburg, Trou moet Blijcken at Haarlem, De Fonteine at Ghent, and De Violieren at Antwerp. See also: duytsche academie

Chambord, Chateau de

A chateau in central France, on the left bank of the River Cosson, a tributary of the Loire, east of Blois. Erected on the site of a hunting lodge and surrounded by forest, the chateau was mainly built (1519-47) during the reigns of Francis I and Henry II and incorporated many Renaissance features. The design was by the Italian architect domenico da cortona and was executed by Jacques Sourdeau, Pierre Neveu, and Denis Sourdeau. Although the chateau was laid out in a medieval Gothic style, its 440 rooms were decorated in a classical manner typical of the Renaissance; other details include a double spiral open staircase. See Plate IV

Champlain, Samuel de

(1567-1635) French navigator, founder of Quebec, and governor of Canada

Hailed as the key figure in the establishment of French interests in North America, Champlain was born at Brouage, his father a sea captain. Champlain fought for Henry IV in the religious wars as a youth and sailed to the West Indies for Spain in 1599, before his first visit to Canada in 1603. For the next five years he explored extensively, before founding Quebec in 1608. He then devoted himself to the welfare of this community, developing the fur trade and making frequent sorties into the hinterland. He became lieutenant of Canada in 1612, but was captured by an English expedition against Quebec in 1629 and taken to England. France regained Quebec in 1632, and Champlain returned the following year to end his days there.

Chancellor, Richard (died 1556) English navigator and mathematician

In his early years he lived in the household of Sir Henry Sidney, where his tutor was John dee. Chancellor applied his mathematical abilities, which Dee rated very highly, to improving navigational techniques, but apparently his first practical experience of seamanship was on a voyage to Chios in 1550. In 1553 he joined the three-ship muscovy company expedition searching for the northeast passage. Although his ship was only one to reach Russia, he completed the hazardous winter journey overland from Archangel to Moscow to negotiate trade terms with Tsar Ivan IV He consolidated Anglo-Muscovite links on subsequent visits in 1555 and 1556, but died in a shipwreck off Scotland while returning from his final journey. His interesting account of Russia was published by hakluyt.

Chanson

A French polyphonic song of the medieval and Renaissance periods. A generic term, "chanson" encompasses rondeaux, ballades, and virelais. machaut can be regarded as the first major chanson composer. In the second half of the 14th century composers regularly set poems polyphonically, usually in three parts, in a rhythmically complex manner. The chansons of dufay were refined, with a rich texture, inventive melodies, and rhythmic variety. Chanson style changed radically around 1500; Josquin des pres and his contemporaries treated each voice independently, and the new technique of imitative counterpoint was used with repetition of phrases. In Paris in the 1530s and 1540s the music printer Pierre Attaig-nant published many chansons, notably those by sermisy and janequin; the Parisian chanson was much simpler in style and more chordal. In the 1550s and 1560s composers used more word-painting, with more variety of texture, though the genre never attained the scope of the madrigal.

Chapman, George

(c. 1559-1634) English poet, playwright, and translator

Little is known for certain about Chapman’s life; he may have been born near Hitchin in southeast England and have attended both Oxford and Cambridge universities without taking a degree. His earliest published poems, The Shadow of Night (1594) and Ovid’s Banquet of Sence (1595), are remarkable mainly for their obscurity; Chapman was never one to wear his learning lightly, a failing also apparent in his continuation of marlowe’s Hero and Leander (1598). He probably began writing for the stage in the mid-1590s, producing such comedies as An Humorous Day’s Mirth (1599) and All Fools (1605). Satirical allusions to the Scots in Eastward Ho! (1605) incurred the displeasure of King James I, causing Chapman and his coauthors Ben jonson and John Marston to be briefly imprisoned. Chapman’s best play is his tragedy Bussy d’Ambois (1607), the hero of which is his finest dramatic creation. Chapman’s greatest achievement, however, was his translation of the whole Homeric corpus: the complete Iliad in rhymed 14-syllable lines appeared in 1611, followed by the Odyssey in rhymed decasyllables (1614-15) and the Homeric hymns (1616).

Charlemagne, legend of

The cycle of narratives, also known as "the matter of France," that accumulated during the Middle Ages around the Frankish king Charlemagne (c. 742-814; emperor 800-814) and his knights (paladins). Much of the earliest material focuses on Charlemagne himself as the divinely appointed champion of Christianity against Islam, but the part of the Charlemagne cycle that really kindled the medieval imagination was the incident in 778 when the rearguard of the Frank-ish army was ambushed by Basques while returning from an abortive campaign in Spain and was annihilated at Roncesvaux in the Pyrenees. This historical kernel grew into the Old French Chanson de Roland (c. 1100), the epic tale of the rearguard’s last stand under its commander Roland against overwhelming hordes of Saracens. The poem was translated into German as the Rolandslied (mid-12th century), and further material was added to the Roland theme in Spanish and Italian poems on the hero’s exploits prior to Roncesvaux and in laments for the slaughtered knights. Grotesque, magic, and erotic elements were also attached to the Roland story, particularly in Italy, and pulci’s Morgante attempts to blend these with the story of Roncesvaux. Roland, Italianized as Orlando, also appears as the hero of the two greatest Italian romantic epics, boiardo’s Orlando innamorato and ariosto’s Orlando furioso, in which the materia cavalleresca of Charlemagne’s wars against the pagans provides the general narrative framework.

Charles V

(1500-1558) Holy Roman Emperor (1519-56); also Charles I of Spain (1516-56), archduke of Austria, and duke of Burgundy

A hapsburg prince, the son of Philip (the Handsome) of Burgundy and Joanna (the Mad) of Castile, Charles inherited vast territories from each of his four grandparents. He succeeded maximilian i as Holy Roman Emperor, inheriting from him Austrian and other German territories. From Mary, heiress of Burgundy, Charles inherited the Netherlands, Franche-Comte, and other territories near the Rhine. From ferdinand ii and isabella i came Spain, Spanish territory in North Africa and the New World, and various Italian territories and claims. By his wife, Isabella of Portugal (1503-39), Charles begot the future philip ii of Spain; two of his illegitimate children—margaret of parma and Don john of austria—also played prominent roles in the late 16th century.

Charles was an earnest, but not particularly intellectual, man. His favorite painter was titian. A devout, if rather unimaginative Catholic, he took his great responsibilities seriously and was determined to protect his faith both against the attacks of the ottoman turks, who reached the gates of Vienna in 1529, and against the Protestants.

Charles was born in Ghent and educated in the Netherlands, where he succeeded his father in 1506 and assumed personal rule in 1515. He was later faced with serious revolts in some Netherlands cities, notably the revolt of Ghent, which was ruthlessly suppressed in 1540. In Spain too there were rebellions early in his reign (see co-muneros, revolt of the), but order was restored by 1522. Charles worked hard to reach an understanding with his Spanish subjects in the 1520s; during his reign Spanish power in the New World was developed and the monarchy in Spain became more unified and centralized.

In Germany, despite some attempts to reach a compromise, as for instance at the colloquy of regensburg, Charles had to confront the Protestant challenge and years of sectarian warfare until the Peace of augsburg (1555) suspended the religious struggle. In Italy, as Maximilian I had done, Charles continued to dispute French claims. The Wars of italy were the most obvious expression of Hapsburg-Valois rivalry for mastery in Europe.

In 1556, exhausted by the burdens of his inheritance, Charles retired to the Spanish monastery of Yuste. His inheritance was divided; Spain, the Netherlands, and other Spanish territories went to his son, Philip II of Spain. Austria, other German territories, and the Holy Roman Empire passed to his brother, ferdinand i.

Charles VIII

(1470-1498) King of France (1483-98) The only son of Louis XI and Charlotte of Savoy, Charles was frail and not very intelligent. During his minority (1483-91), Anne de Beaujeu, his sister, and her husband were regents. They administered France soundly and by arranging Charles’s marriage (1491) to Anne, heiress of Brittany, eventually secured Brittany for the French royal domain. This marriage infuriated Anne’s erstwhile fiance, maximilian i, and presaged the long Hapsburg-Valois conflict. On attaining his majority Charles was able to pursue his dreams of conquest, chivalry, and a crusade against the Turks. His first step was to assert French claims in Italy. After making costly treaties to buy off possible enemies, Charles invaded Italy (1494). He met little opposition; savonarola welcomed him as a liberator to Florence, the pope opened the gates of Rome, and Naples surrendered without a fight. Charles was crowned king of Naples (May 1495), but France’s enemies formed a league against her. Charles abandoned Naples to the Aragonese and fought his way back to France, where he died while preparing another Italian invasion.

Charles Borromeo, St.

(1538-1584) Italian churchman Born at Arona, Borromeo was destined from childhood for the Church and in 1560 was appointed cardinal archbishop of Milan by his maternal uncle, Pope Pius IV Until Pius IV died (1565) Cardinal Borromeo served in the Curia, playing an important part in the later sessions of the Council of trent and drafting the Roman catechism. After 1566 he devoted himself to the archdiocese of Milan. He reformed its administration, improved the morals of clergy and laity, supported the Jesuits, helped establish seminaries and religious schools, and aided the poor and sick. His heroic efforts during an outbreak of plague (1576-78) were much admired. A leading figure in the counter-reformation, he was canonized in 1610.

Charles the Bold

(1433-1477) Duke of Burgundy (1467-77)

The son of philip the good, Charles was a rash man, who inherited extensive territories. His great ambitions were to gain a royal title and to win Alsace and Lorraine, the lands dividing his domains in the Netherlands from those in the Franche-Comte. He came close to realizing his first ambition, when Emperor Frederick III was on the brink of making Burgundy a kingdom. In pursuit of his second ambition he acquired power in Alsace and attacked Lorraine (1475). Alarmed at the prospect of a Burgundian kingdom stretching from the North Sea to the Alps, his neighbors combined against him. He died fighting the Swiss at Nancy and left his daughter Mary as his heiress. Her marriage to maximilian i conveyed most of the Burgundian inheritance to the house of hapsburg.

Charron, Pierre

(1541-1603) French writer and moralist Born in Paris, he was one of a family of 25 children. After studying law at Orleans and Bourges he practiced as an advocate but became disenchanted with the profession. He turned to the Church and enjoyed a distinguished career as a preacher, becoming chaplain-in-ordinary to Margaret of Valois, first wife of Henry of Navarre. In 1588 he returned to Paris determined to join a religious order, but, when none would accept him because of his age, he retired to Bordeaux where he became close friends with montaigne. Charron published anonymously a treatise on Les Trois Verites (The Three Truths; 1593), which combined an apology for Catholicism with an attack on du plessis-mornay. He died in Paris of a stroke.

Charron’s most important work was De la sagesse (On Wisdom; 1601). The main thesis of this work was the incapacity of reason to discover truth and the need for tolerance on religious questions. The work was severely censured by the Sorbonne and was a forerunner of 17 th-century deism.

Chaucer, Geoffrey

(c. 1343-1400) English poet Born the son of a rich London wine merchant, Chaucer was brought up in the household of the earl of Ulster. Captured by the French near Reims while serving with the English army, he was ransomed by Edward III (1360). He then visited Spain (1366) before joining the royal household in 1367. In 1369 or 1370 he produced his first important poem, The Book of the Duchess, commemorating the recently dead Blanche of Lancaster. He made two visits to Italy, the first on business with the Genoese (1372-73), the second (1378) negotiating with Bernabo Visconti of Milan. From 1374 to 1386 he was a customs controller in the port of London. Poems of the early 1380s include The House of Fame, The Parliament of Fowls, and Troilus and Criseyde. Around 1387 he began work on The Canterbury Tales. From 1385 he was associated with the county of Kent in some of his many official capacities and probably lived there until he moved to a house near Westminster Abbey in 1399. He was interred in the abbey the following year.

Acknowledged by his Renaissance successors as the greatest of earlier English writers, Chaucer was an important figure to them on several counts, despite what seems to us the thoroughly medieval nature of his poetry. First, his learning was singled out for special admiration, for instance in the dedication to the first complete edition of his works, published in 1532. The moral lessons implicit in his poetry particularly appealed to an age which held that "wholesome counsel and sage advice" (William Webbe, Discourse of English Poetry, 1586) should be mingled with "delight."

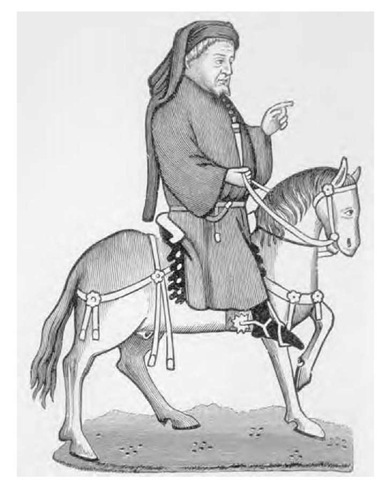

Geoffrey Chaucer An engraving based on an illumination in the Ellesmere manuscript (c. 1410) of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. This is the earliest known likeness of the poet. Mary Evans Picture Library

However, it was in his role of "Dan Chaucer, well of English undefyled" (Spenser, the faerie queene IV ii 32) that he most influenced the literature of the English Renaissance. caxton’s proem to his second edition of The Canterbury Tales (1484) praises Chaucer as "that noble and grete philosopher" who "enbelysshed, ornated, and made faire our Englisshe," and the theme was taken up by several subsequent writers on the development of the vernacular, although sidney in his Defence of Poesie was more guarded: "I knowe not whether to mervail more, either that hee [Chaucer] in that mistie time could see so clearly, or that wee in this cleare age, goe so stumblingly after him. Yet had hee great wants, fit to be forgiven in so reverent an Antiquitie."