Alessi, Galeazzo

(1512-1572) Italian architect Alessi was born in Perugia and later (1568) designed the principal doorway for the cathedral there. He visited Rome in the late 1530s and his style was formed by his enthusiasm for classical architecture, especially as mediated by michelangelo. His most distinguished work combines the dignity of the classical orders with sumptuous detail, as exemplified in the courtyard of the Palazzo Marino, Milan (1553-58). From 1549 onward he designed a number of notable buildings in Genoa, among them the church of Sta. Maria Assunta di Carignano (begun 1552) and some fine villas and palaces in the Strada Nuova (now the Via Garibaldi), which he himself may have laid out. Other examples of his work appear in the Certosa di Pavia (sarcophagus of Giangaleazzo Visconti), at Brescia (the upper part of the Loggia), and Bologna (gateway to the Palazzo Communale; c. 1555). His style was much admired and influenced buildings as far afield as Spain and Germany, especially after rubens published Palazzi di Genova (1622), a study in which Alessi’s Genoese work features prominently.

Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia)

(1431-1503) Pope (1492-1503)

He was born at Xativa, Spain, studied law at Bologna, and was first advanced in the papal service by his uncle Alfonso Borgia, Pope Calixtus III, under whom he became head of papal administration, a post which he held ably for 35 years (1457-92). Political corruption and immorality in the Vatican reached their height under Alexander, deeply involved as he was in the struggle between the leading Italian families for power and wealth (see borgia family). His contribution to the secularization of the Curia probably enhanced the spreading popularity throughout Italy of preaching friars who condemned the papacy and called upon clergy and laity to repent.

Alexander’s pontificate was set against the background of the Wars of italy. When charles viii of France invaded Italy (1494), seizing Rome and Naples, Alexander helped organize the League of Venice, an alliance between Milan, Venice, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire, which was successful in forcing Charles to leave Italy. However, in the interests of the Borgias, particularly of his son Ce-sare, he later adopted a pro-French policy and aided the French invasion that led to their occupation of Milan in 1499. Monies from the jubilee year, proclaimed by Alexander in 1500, were diverted to Cesare to help him finally crush the Orsini and Colonna families. The marriages of Alexander’s daughter Lucrezia borgia were also directed towards political ends.

During Alexander’s pontificate Spain laid claim to the New World, following the discoveries of columbus, and it was Alexander who determined the Spanish and Portuguese spheres of influence there (see tordesillas, treaty of). He is also remembered as a patron of artists and architects, including bramante and pinturicchio. The diary of Johann Burchard (died 1506), Alexander’s master of ceremonies, gives an intimate account of life close to this most notorious pope; it was published under the title Historia arcana (1597) and in an English version as At the Court of the Borgia (1963).

Alfonso I

(1395-1458) King of Naples (1442-58) and (as Alfonso V) king of Aragon (1416-58)

Known as Alfonso the Magnanimous, he was admired as a model prince and a devout Christian. The son of a Castil-ian prince, who became Ferdinand I of Aragon in 1412, and of Leonor of Albuquerque, he was brought up in Castile and moved to Aragon in 1412. In 1415 he married Maria of Castile; their marriage was unhappy and childless. After succeeding to Aragon in 1416 Alfonso angered his subjects by relying on Castilian advisers, but he did follow the Aragonese tradition of expansion in the Mediterranean. In 1420 he set out to pacify his Sicilian and Sardinian subjects and to attack the Genoese in Corsica. He arrived in Naples in 1421 and persuaded Queen Joanna (Giovanna) II to adopt him as her son and heir in exchange for his help against the Angevin claimant to the throne of Naples. After quarreling with Joanna in 1423 he returned to Spain and busied himself with Spanish problems until her death in 1435. Alfonso then returned to Naples to claim his throne and succeeded in driving out his main rival, rene of anjou, after seven years of struggle. He left the government of his other territories to viceroys and settled permanently in Naples from 1443. He reorganized its finances and administration and made his court at Naples a brilliant center of learning and the arts. Understanding the importance of presenting himself as a Renaissance prince, Alfonso employed some major humanist figures about his court: Lorenzo valla wrote several of his most significant works during his decade in Naples, while Antonio beccadelli and Bartolomeo Facio (or Fazio; c. 1400-47) combined work in Alfonso’s secretariat with writing accounts of his reign. The triumphal arch at the Castel Nuovo in Naples (built 1453-66) commemorates Alfonso’s grand entry into the city in 1443. He died in battle against Genoa, leaving Naples to his illegitimate son, Ferrante (ferdinand i); his other domains passed to his brother John.

Alfonso II

(1448-1495) King of Naples (1494-95) The son of ferdinand i (Ferrante) and Isabella of Naples, Alfonso, who was cowardly and cruel, was very unpopular. Before succeeding his father, he was associated with and blamed for much of his father’s misrule. Through his marriage to Lodovico Sforza’s sister, Ippolita, and through his sister’s marriage to Ercole d’Este of Ferrara, Alfonso was involved in various Italian conflicts. He defeated Florence at Poggio (1479) and the Turks at Otranto (1481). When charles viii of France was advancing on Naples early in 1495 Alfonso abdicated in favor of his son, Ferdinand II (Ferrantino), and died later the same year.

Algebra

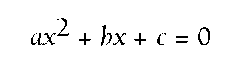

While ancient mathematicians made enormous contributions to geometry and arithmetic, their achievements in algebra were less impressive. A tendency to solve problems geometrically, and the failure to develop a convenient symbolism, had led the Greeks in a different direction, but the subject was developed by Indian and Muslim mathematicians, who bequeathed to the Renaissance a number of simple rules for the solution of equations. While Renaissance mathematicians made significant advances in the theory of equations, they proved less successful in developing an adequate symbolism. There was little uniformity of symbolism, and notation was cumbersome and unhelpful. The simple equation

where x is the unknown, and a,b,c, stand for given numbers could not have been written before 1637. The equality sign (=) was introduced by Robert Recorde in 1537, and the custom of equating the function to zero was established by Rene Descartes in 1637.

Exponents proved more troublesome. In his In artem analyticam isagoge (1591) Francois viete had, following the Greek custom, written A2, A3, as AQ, and AC, where the Q and C stood for "quadratus" and "cubus" respectively. The modern convention of A2 and A3 dates, once more, from Descartes, as does the use of letters of the alphabet to stand systematically for the unknowns. The 16th-century Italian mathematicians tartaglia and car-dano would have written the equation

as cubus p: 6 rebus aequilis 12 which translates as a cube plus 6 things equals 12.

Despite the opacity of their notation, Tartaglia and Car-dano still managed to make the first major breakthrough in modern algebra. Neither Greek nor medieval mathematicians had worked out a suitable algorithm for the solution of cubic or higher equations. Algebra seemed stuck at the level of quadratics. In this latter field bombelli had shown how quadratics could be solved by completing the square, while solution by factorization was first worked out by Harriot. Linear equations, by contrast, tended to be solved by a number of traditional rules. Known by such names as "the rule of false position" and "the method of scales," they could be applied quite mechanically.

There remained the cubic equation. In 1535 Tartaglia publicly solved 30 cubics in a competition with the Italian mathematician Scipione del Ferro. Four years later he revealed his algorithm to Cardano, who unhesitatingly published his own variant of the solution in Ars magna (1545). Cardano also reported on the solution of the biquadratic or quartic discovered by his pupil Ludovico Ferrari (1522-c. 1560). To advance further, however, required the possession of techniques unknown to Renaissance mathematicians.

Allen, William

(1532-1594) English Roman Catholic scholar and cardinal (1587)

Refusal to comply with the conditions of the Protestant settlement under Elizabeth I obliged him to relinquish his academic post at Oxford and in 1565 to go into permanent exile. He devoted his life to the training of priests for missions to England to reclaim the country for the Roman Catholic Church, establishing colleges for that purpose at douai (1568), Rome (1575), and Valladolid (1589), and instigating the Douai-Reims translation of the Bible into English. However, his backing for the attempted Spanish invasion of England in 1588 alienated many English Catholics. He died at the english college, his foundation in Rome.

Alleyn, Edward

(1566-1626) English tragic actor and theatrical impresario

Having made his reputation on the London stage in the 1590s, he went into partnership with Philip Henslowe (died 1616) to build the Fortune Theatre (1600). In 1604 they became joint masters of the royal bear-baiting establishment. Alleyn’s performances in roles such as marlowe’s Faustus earned him comparisons with the classical Roman actor Roscius. A shrewd businessman, he amassed a considerable fortune from his theatrical and other properties, using it to buy up the manor of Dulwich, southeast of London, where he founded (1616-19) "the College of God’s Gift," now the public school Dulwich College.

Allori, Alessandro

(c. 1535-1607) Italian painter Allori was active in Florence, where he studied under his uncle bronzino, of whom he was a close follower. A visit to Rome (1554-56) also brought him under the influence of michelangelo, which is visible in his frescoes from the early 1560s in SS. Annunziata, Florence. He was patronized by Francesco I de’ Medici and contributed paintings in the manner of Bronzino to the duke’s Studiolo in the Palazzo Vecchio. Other work for the Medici includes decoration in the Salone of their villa at Poggio a Caiano. His later works, among them a Birth of the Virgin (1602; SS. Annunziata, Florence) and an Ascension (1603; San Michele, Prato), are in a softer, more relaxed style. His son Cristofano (1577-1621) followed the emerging baroque tendency in Florentine art. Cristofano’s best-known picture, Judith (Palazzo Pitti, Florence), incorporates portraits of the artist and his wife.

Altdorfer, Albrecht

(c. 1480-1538) German painter, print maker, and architect

The son of an illuminator, Altdorfer became a citizen of his home town of Regensburg in 1505. A member of Re-gensburg city council since 1519, he was appointed surveyor of public buildings in 1526. In 1535 he was chosen as an ambassador to Vienna, possibly because of his knowledge of the region.

Together with Wolf huber and the young cranach, Altdorfer was a chief exponent of the socalled "Danube style". Possibly influenced by the pastoral poetry of Kon-rad celtis, these painters delighted in portraying the lush vegetation and dreamy enchantment of the German woods. This fascination with the luxuriance of nature is strongly apparent in Altdorfer’s tiny Berlin Satyr Family (1507). Despite the emphatically Germanic location of this scene, the figures are Italian in derivation; the artist copied engravings after mantegna from as early as 1506. In the Berlin Nativity (c. 1512) Altdorfer utilized dramatic lighting effects and one-point perspective with brilliant effect. This fundamental bent towards Mannerism developed still further in the eerie viewpoints and stunning colors of the now dismantled altarpiece (1517) for St. Flo-rian near Linz. The high point of Altdorfer’s career is his Munich Battle of the Issus (1529), one of the great visionary paintings of all time. Depicted from an almost astral viewpoint, the forces of Alexander the Great pursue the hordes of Darius into Asia. The background landscape curves to reveal the rim of a spherical earth upon which Cyprus and the North African coast may be plainly seen, upside down, as though viewed from the north and an immense height. Altdorfer was also outstanding as a draftsman of chiaroscuro drawings and a designer of woodcuts. He was arguably the most individual genius in German painting of the 16th century.

Altichiero

(1320/30-1395) Italian painter Altichiero was born at Zevio, near Verona, and was mainly active in Verona and Padua. His style was influenced by giotto and he himself had numerous followers. Frescoes by him can be seen in San Stefano and Sant’ Anastasia in Verona and in the Santo and Oratorio di San Giorgio in Padua.

Amadeo, Giovanni Antonio

(1447-1522) Italian marble sculptor

He was born in Pavia and is documented from 1466 working on sculpture for the magnificent new Certosa (Carthusian monastery) in his native town; in 1474 he was made jointly responsible with the brothers Mantegazza for its huge polychrome marble facade. Between 1470 and 1476 he carved the monuments and reliefs of the Colleoni chapel in Bergamo and in 1490 was employed on Milan cathedral. Apart from portraits, in which his work was influenced by classical prototypes, his sculpture was mostly carved in relief, with religious themes predominating.

Amberger, Christoph

(c. 1500-61/62) German painter Amberger was born at Augsburg and probably trained there under Hans burgkmair and Leonhard beck. In 1548 he met titian, then visiting Augsburg. Amberger’s Berlin portrait of Charles V (c. 1532) was influenced by the Netherlandish court painter Jan vermeyen, who was at Augsburg in 1530. References to the Venetian painters palma vecchio and Paris bordone appear in Amberger’s

Vienna portraits of a man and a woman (1539) and his Munich Christoph Fugger (1541). In the Berlin portrait of Sebastian munster (c. 1552), Amberger eschewed this international mannerist style in favor of a more traditional German approach. His altar for Augsburg cathedral (1554) is similarly conservative, translating the late Gothic architectual motifs of holbein the elder into a contemporary Italianate idiom.

Ambrosiana, Bibliotheca

The chief library of milan, founded by the bishop of Milan, Cardinal Federico Bor-romeo (1564-1631), who named it after St. Ambrose, patron saint of the city. It was the first public library in Italy and opened on December 8, 1609, with a collection of over 30,000 books and 12,000 manuscripts housed in the palace built by Borromeo between 1603 and 1609 on the site of the Scuole Taverna. The library was enriched by many private donations and bequests, as well as by the acquisitions of its agents traveling abroad.

Ambrosian Republic

(1447-50) A Milanese regime established immediately after Duke Filippo Maria Visconti (see visconti family) died without an heir. Twenty-four local notables—"captains and defenders of liberty"— named the republic in honor of St. Ambrose, Milan’s patron. Divisions within the ruling group, discontent from the lesser bourgeoisie, rebellion in subject cities, and the hostility of Venice brought the republic close to collapse. In autumn 1449 Francesco sforza, a condottiere formerly in Duke Filippo Maria’s employ and married to the duke’s illegitimate daughter, besieged the city; in March 1450 the republic surrendered and Sforza was installed as duke of Milan.

Amerbach, Johannes

(1443-1513) Swiss printer and publisher

He studied in Paris and then returned to Basle to set up a printing house (1475) with the principal aim of producing good texts of the works of the Church Fathers (see also patristic studies). He gathered round him a circle of scholars that included reuchlin, and in 1511 employed a Dominican, Johannes Cono of Nuremberg (1463-1513), to instruct his sons and any other interested parties in Greek and Hebrew in his own house, which became a virtual academy for northern European scholars. This intellectual tradition was continued by Amerbach’s successor, froben.

Ames, William (Amesius)

(1576-1633) English Puritan divine

Ames was born at Ipswich. Having gained a reputation as a controversialist while at Cambridge, he left England for the Netherlands after being forbidden to preach at Col chester by the bishop of London. Here he soon made a name for himself as the champion of Calvinism in his debate with the minister of the Arminians (see arminianism) at Rotterdam in 1613. Between 1622 and 1633 he was professor of theology at Franeker university in Friesland, where his reputation was such that he attracted students from all over Europe. Ill health led to his resignation and he died at Rotterdam a few months later.

Amman, Jobst

(1539-1591) Swiss-born print maker and designer of stained glass

The son of a choirmaster and teacher of rhetoric, Amman worked first as a stained-glass designer in his native Zurich before moving, successively, to Schaffhausen, Basle, and Nuremberg. Although he is not documented as an assistant of Virgil solis, he was effectively the latter’s successor as the leading book illustrator in Nuremberg. His voluminous output included numerous ornamental and heraldic prints and title-pages, as well as narrative illustrations. He received numerous commissions from humanists and editors, such as Sigmund Feyerabend of Frankfurt. In 1574 he married the widow of a Nuremberg goldsmith and became a citizen of his adopted city. On account of his commissions he traveled widely: to Augsburg (1578), Frankfurt and Heidelberg (1583), Wurzburg (1586-87), and Altdorf (1590). Amman’s penetrating portraits, such as Hans Sachs and Wenzel Jamnitzer, and his genre works and studies, such as the Series of Animals, constitute his finest work.

Ammanati, Bartolommeo

(1511-1592) Italian sculptor Born near Florence, Ammanati trained in the workshop of Pisa cathedral, where his first independent work is found (1536). In 1540 he tried to make his mark in Florence with a private commission for the tomb of Jacopo Nari, but it was sabotaged by the jealous bandinelli, leaving only the effigy and a good allegorical group of Victory (both Bargello, Florence). Ammanati left for Venice, where he was helped and influenced by his fellow-countryman Jacopo sansovino. His principal sculptures in north Italy were Michelangelesque allegories for the palace and the tomb of the humanist Marco Benavides (1489-1582) in the Eremitani church in Padua.

After Pope Julius III was elected (1550) Ammanati moved to Rome, where he executed all the sculpture on the monuments to members of the pope’s family in San Pietro in Montorio. The portrait effigies and allegories are among Ammanati’s masterpieces. Moving with vasari to Florence, he entered the service of the Medici dukes. His spectacular fountain of Juno has six over-life-size marble figures mounted on a rainbow (components now in the Bargello). Ammanati’s best-known sculpture is the fountain of Neptune in the Piazza della Signoria, Florence (c. 1560-75). The central figure was carved out of a colossal block of marble already begun by Bandinelli before his death (1560); this inhibited Ammanati’s treatment. More successful are the surrounding bronze figures of marine deities, fauns, and satyrs, modeled and cast under his supervision. These figures and his Ops, a female nude statuette that Ammanati contributed (1572-73) to the Studiolo of Francesco de’ Medici, epitomize his style, which concentrates on grace of form at the expense of emotion. Ammanati rivalled Vasari as a mannerist architect, with his amazingly bold but capricious rustication in the courtyard of the Palazzo Pitti (1558-70) and his graceful bridge of Sta. Trinita (1567-70). By 1582 the counter-reformation had so strongly influenced the sculptor that he denounced on moral grounds the public display of nude sculpture.

Amsdorf, Nikolaus von

(1483-1565) German Lutheran theologian

Probably born at Torgau on the Elbe, Amsdorf studied at Wittenberg, where he later met luther. He soon became a close friend and one of Luther’s most determined supporters. Amsdorf assisted in the translation of the Bible and accompanied Luther to the Leipzig conference (1519) and the Diet of worms (1521). He became an evangelical preacher, spreading word of the Reformation at Magdeburg (1524), Goslar (1531), Einbeck (1534), and Schmal-kald (1537). John Frederick, Elector of Saxony, appointed him bishop of Naumburg-Zeitz in 1542, a post he held until 1547. In 1548 he helped found the university of Jena, and, in the same year actively opposed the Interim of augsburg. From 1552 until his death he lived at Eisenach, remaining a conservative and influential Lutheran.

Amsterdam

A Netherlands city and port on the Ijs-selmeer, an inlet of the North Sea. As a small fishing village Amsterdam gained toll privileges from Count Floris V of Holland in 1275 and prospered during the Renaissance to become Holland’s largest commercial center by the late 15th century. Political developments, combined with the expansion of trade, fishing, and shipbuilding, made 16th-century Amsterdam one of the greatest European financial and commercial centers. Its citizens rejected Spanish rule and adopted the Calvinist cause under the leadership of william the silent (1578); they profited from the Spanish recapture of Antwerp (1585) and the subsequent closure of the River Scheldt to trade. By the early 17th century Amsterdam had close to 100,000 inhabitants and could claim to be not only Europe’s financial capital but also a center of world trade, especially the tea and spice trades. Its institutions included the Dutch East India Company (founded 1602), the Amsterdam exchange bank (founded 1609), and the Amsterdam stock exchange. The Nieuwe Kerk is the city’s most notable surviving Renaissance building.

Amyot, Jacques

(1513-1593) French bishop and classical scholar

Born at Melun and educated at Paris university, he became professor of Latin and Greek at Bourges, where he began his work of translating classical authors: Heliodorus (LHistoire ethiopique, 1548), Longus (Daphnis et Chloe, 1559), and, above all, plutarch. His translation of Plutarch’s Lives, finally completed under the patronage of Francis I in 1559, supplied the writers and playwrights of several generations with characters and situations. Retranslated into English by North (1579), this was Shakespeare’s major source for his Roman plays. Amyot’s version of Plutarch’s Moralia appeared in 1572, completing a task that made him deservedly hailed by his contemporaries as "le prince des traducteurs." Favored by four successive French kings and tutor to two of them, Amyot was finally made bishop of Auxerre in 1570, where he spent the rest of his life.

Anabaptists

A variety of separate religious movements on the radical wing of the reformation. The Anabaptists emerged from the underprivileged layers of society, often with exceptionally radical social, economic, and religious programs. Features common to all included the practice of adult baptism (hence the term "Anabaptists," coined by their enemies), a belief in continual revelation, and a doctrine of separation from the unconverted. Consequently they gained a reputation as dangerous revolutionaries, intent on the destruction of the established social and religious order.

Anabaptist activity in Munster

(1532-35) marks the peak of their political influence. Religious radicals such as the preacher Bernhard Rothmann (c. 1495-c. 1535) and the merchant Bernhard Knipperdollinck (c. 1490-1536) combined to turn Munster into an Anabaptist city, a situation temporarily condoned by Landgrave philip of hesse. The existing order in Munster was overthrown in 1534 by Dutch Anabaptists led by Jan Matthysz., a baker of Haarlem, and John of Leyden (Jan Leyden) who hoped to turn the city into a New Jerusalem from which the spiritual conquest of the world could be directed. Matthysz. ordered the confiscation of all property and destruction of all books except the Bible. His followers’ iconoclasm brought about the destruction of much of Munster’s heritage of religious art. The prince-bishop besieged the city, and Matthysz. was killed during a sortie (April 1534). John of Leyden then proclaimed himself "king" and introduced polygamy. The prince-bishop captured the city in June 1535, and the following January the surviving Anabaptist leaders were tortured and executed. The end of the Anabaptist "kingdom" of Munster was not the end of Anabaptism, which had extended into other parts of northern and central Europe. The chief centers of activity were Saxony, Zurich, Augsburg and the upper Danube, Austria, Moravia, the Tyrol, Poland, Lithuania, Italy, the lower Rhine, and the Netherlands. Groups in these places often held differing doctrinal views, although united in their rejection of infant baptism. Menno Simons (see men-nonites) was the leader of one such group. Others were the Melchiorites or Hoffmanites (called after their leader Melchior Hoffman) in the Netherlands; the Hutterites (after their leader Jakob Hutter) in Moravia; the socalled Zwickau Prophets in Saxony; and the Swiss Brethren. All were liable to often savage persecution from their Catholic and Protestant neighbors.

Anamorphosis

In art, an image distorted in such a way that it only becomes recognizable when viewed from a particular angle or under certain other conditions. The transliteration of the Greek word (meaning "transformation") did not appear until the 18th century, but is generally used to refer to earlier compositions. Plato (Sophist, 236) was the first to make mention of the idea. It was re-introduced explicitly by Daniele barbaro in his Pratica della perspettiva, published in Venice in 1568/69, with the following definition: "Often, and with no less pleasure than amazement, one may gaze on some of those pictures or cards showing perspectives in which, if the eye of s/he who looks at them be not placed at a particular point, something totally different from what is depicted appears, but, contemplated afterwards from its correct angle, the subject is revealed according to the painter’s original intention."

For the painter, anamorphosis is a special application of the laws of perspective. Shapes are projected outside themselves and dislocated in such a way that they re-form when they are seen from another viewpoint. The practice of anamorphosis shows that artistic technique could have other aims than that of restoring a third dimension (the sole aim recognized in alberti’s treatises). The "curious" perspective of anamorphosis is, rather, a stimulus to fantasy and an illustration of the fleeting, oblique nature of pictorial truth. The earliest examples of the technique in the Renaissance are met with in the notebooks of leonardo da vinci. The two best-known examples of anamorphosis in painting are the skull in holbein’s Ambassadors (1533; National Gallery, London) and Guilim (William) Scrots’s portrait of the future King edward vi (1546; National Portrait Gallery, London). The latter, displayed at Whitehall Palace, apparently had some special viewing device attached to it to enable the head to be seen in correct perspective.

Anatomy

Renaissance anatomists worked almost exclusively in the tradition established by the 2nd-century Greek physician Galen (see galenism, renaissance). The tradition is clearly seen in the Anathomia (1316) of Mondino de’ Luzzi, the leading textbook of the early Renaissance. It suffered from two basic weaknesses. In the first place, because of constraints on human dissection, anatomists had often been forced to work with Barbary apes and domestic animals. For this reason they readily followed Galen in describing the rete mirabile, a vascular structure they had all supposedly seen at the base of the human brain, despite the fact that it is found in the ox and the sheep but not in man. Once such fictions as the rete mirabile and the five-lobed liver entered the literature, they seemed impossible to eliminate. Secondly, anatomy was made to serve the misguided Galenic physiology. If Galen’s system needed septal pores to allow blood to pass directly from the right to the left side of the heart, they were conveniently "seen" and reported. To overcome these difficulties it would be necessary to prefer the evidence of nature to the authority of an ancient textbook.

The first real signs of such a transfer of allegiance can be seen in the early 16th century. Monographs revealing this tendency were produced by leonardo da vinci, Berengar of Carpi (died 1530), Charles estienne, Gunther of Andernach (1487-1584), Jacobus Sylvius (1478-1555), and, above all, vesalius. The new-style monograph used the full resources of Renaissance artists and printers to provide, for the first time, detailed realistic illustrations, whereas earlier works had provided no more than extremely crude stylized diagrams. Moreover, anatomy was becoming a subject of serious artistic study in its own right, with Leonardo and Antonio del pollaiuolo leading the way, followed closely by michelangelo. A detailed account of the fruits of anatomical studies for artists appears in lomazzo’s Trattato (1584). The first printed anatomical figures appeared in the Fasciculo de medicina (1493); 50 years later the De fabrica of Vesalius contained some 250 detailed blocks by Jan Steven van calcar. At last anatomists had something objective against which to judge their own observations. They soon came to realize that items such as septal pores and five-lobed livers could not be found in the human body.

Once having seen that the traditional account of human anatomy was questionable, anatomists could begin the serious task of restructuring their discipline. Part of this task involved the construction of a new vocabulary. Many terms such as "pancreas" and "thyroid" came from Galen himself; others came from Arabic and Hebrew sources; the bulk, however, came from Renaissance anatomists. The Renaissance also saw the emergence of the new discipline of comparative anatomy. belon in 1551 had written on the anatomy of marine animals, while Carlo Ruini in his Anatomia del cavallo (1599) tackled the anatomy of the horse. On the basis of such detailed monographs Giulio Casserio (1561-1616) could at last present genuinely comparative material in his De vocis auditusque organis (1601), a study of the vocal and auditory organs of man, cow, horse, dog, hare, cat, goose, mouse, and pig.