Archives. New Jersey has thousands of collections of records from the past, which provide valuable information to historians, scholars, genealogists, and other researchers. Most of these collections are preserved in special repositories known as archives. An archive is a special library established by an institution to collect and preserve its own records and history.

The state of New Jersey maintains an archive in Trenton to collect and preserve all official state records—vital records of births, deaths, estates, and much more—dating from the earliest colonial days to the present. County and municipal governments have established archives to collect and store their own records. Several hundred county and local historical societies also preserve and collect materials; the New Jersey Historical Society and many local historical societies maintain New Jersey archives of great value.

Many large archives contain much more than the official records of their own institutions. Princeton University, Rutgers University, and others hold vast collections of materials relating to New Jersey history, as well as special collections of rare materials. These include medieval manuscripts and ancient records from all over the world, written in many languages, on clay tablets, parchment, vellum, and palm leaves. Some public libraries, such as the Newark Public Library, maintain large archives of rare materials. Large corporations often have archives of their business records, correspondence, and official acts, and religious-affiliated institutions such as Seton Hall University and Drew University have established central archives to preserve the records of their particular denominations.

Directory of County Historical Societies in New Jersey, 2001. Freehold: Monmouth County Historical Association, 200i.

Argall, Samuel (b. c. 1580; d. Mar. 1626). Sea captain, explorer, and agent of the Virginia Company. Sir Samuel Argall was born to English landowner Richard Argall and Mary Scott of Kent. He fought for England on land and sea before serving the Virginia Company as a sea captain beginning in 1609, and set records for the speed of his Atlantic crossings. He explored the New Jersey seacoast in 1610 while seeking supplies for Virginia, and again in 1613 on his way to attack the French in Maine. He served as the deputy governor of the Virginia Company from May 15, 1617, to April 10,1619. He had neither wife nor children and died fighting the Spanish at sea near Cadiz in January 1626.

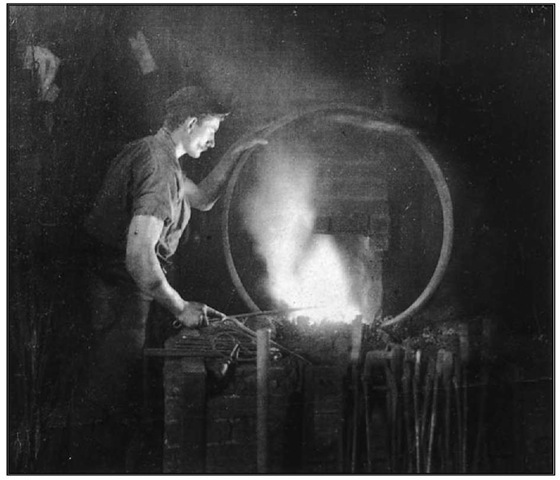

William Armbruster, The Smithy, n.d. Orange-toned carbon print, 6 x 71/8 in.

Armbruster, William (b. Mar. 24, 1865; d. Feb. 28, 1955). Photographer. William Armbruster was born in Brooklyn, New York. When he was sixteen his father, Charles, moved the family to Jersey City where he owned and operated Greenville Schuetzen Park. This large and socially prominent club— which hosted shooting matches, equestrian events, and civic functions—also served as a home for the Greenville Camera Club, and Armbruster was its most accomplished member, documenting life in the park in a straightforward manner, photographing visitors, neighbors, and family. He also composed atmospheric carbon and platinum prints of landscapes and portraits that are typical of pictorial photography at the turn of the twentieth century. Late in life Armbruster kept a summer home in the utopian community of Free Acres (Berkeley Heights), where he also found many subjects to photograph.

Armenians. Fleeing the social and political turmoil of their ancestral homeland in the Caucasus and Eastern Anatolia, the earliest Armenian immigrants started settling in New Jersey in the 1890s. For the most part, they found factory jobs in Paterson, Camden, and West Hoboken. Immigration was accelerated by the 1915 genocide of Armenians in Turkey. Since 1965, a new wave of Armenians has arrived from the Middle East and the former Soviet Union. The 2000 U.S. Census recorded 17,094 people of Armenian descent living in New Jersey. The ratio of immigrant generation to American-born is roughly 60/40.

As early as 1898, three Armenian congregations conducted services in rented halls in New Jersey. Holy Cross Armenian Church, built in Union City in 1906, serves the oldest congregation to remain in its original location. The Armenian Presbyterian Church was relocated to Paramus in 1972. Other Apostolic/Orthodox churches are found in Elberon, Livingston, Ridgefield, Fair Lawn, and Tenafly. In the 1990s, the Sacred Heart Catholic Armenian Church was established in Little Falls. The twenty-five-year-old Hovnanian Armenian School in New Milford serves approximately 150 full-time students, from pre-kindergarten to eighth grade.

Between the 1930s and 1970s, Asbury Park was a favorite summer rendezvous spot for Armenians from all along the East Coast. The Lincoln, Fenimore, Hye, and Van hotels were operated by Armenians, and Armenian music and dancing were featured every weekend.

Art. Notwithstanding the state’s significant position between New York and Philadelphia, historically two of America’s most prominent centers of artistic activity, the contributions of New Jersey’s artists have suffered from a lack of attention by the critics and the media. Yet it is clear that several of the nation’s most important artists have lived and worked in the Garden State.

Although New Jersey artists did not lead but essentially followed the subject matter and styles developed outside the state, some distinguished New Jersey practitioners nevertheless can be identified. As early as the eighteenth century, when portraiture served a purpose aside from being an accepted art form, prominent portrait painters established their homes and studios in New Jersey, and others visited and worked in the state. The wax portraiture of Bordentown’s Patience Lovell Wright (1725-1786); the paintings and sculpture of her son Joseph (17561793); and the portraits of John Watson (16851768) of Perth Amboy, for example, have remained impressive and lasting works of art. In 1783, just before the conclusion of the American Revolution, Joseph Wright is known to have created a life mask of George Washington at his headquarters at Rocky Hill, and also portrayed him in both painting and sculpture. Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828), America’s most important early portrait painter, worked for a short period in Borden-town, and the portrait and history painter Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), who also took part in the Battle of Trenton, painted in New Jersey. In the nineteenth century, even as new art forms developed, portraiture remained an important feature of the work of several New Jersey artists, including Henry In-man (1801-1846), who maintained a studio in Mount Holly beginning in 1832, and Lilly Martin Spencer (1822-1902), who settled in Newark in 1858.

New Jersey artists also played a major role in the development of nineteenth-century landscape, marine, and seascape painting. Picturesque areas including the Jersey Meadows, the New Jersey Shore, and the Falls at Passaic attracted several artists. Indeed, the development of the Hudson River school, the nation’s most important group of nineteenth-century landscape painters, was largely due to the talent and efforts of Asher B. Durand (1796-1886), who became a resident of Jefferson Village (now Maplewood) in 1869. And in 1878, George Inness (1825-1894), generally acknowledged as one of America’s preeminent painters of subjective and idealized landscapes, and Worthington Whittridge (1820-1910), a major Hudson River school painter, were residents of Montclair and Summit respectively.

Women artists were also represented in nineteenth-century landscape painting circles, most notably Julia Hart Beers Kempson (1835-1913), who lived and worked in Metuchen. In the area of marine painting, Winslow Homer (1836-1910) visited the New Jersey Shore in 1869, where he painted one of his most famous works, Long Branch, New Jersey. And the Atlantic City paintings of William Trost Richards (1833-1905), the marine paintings of James Buttersworth (1817-1894), and the steamship portraits of Antonio Jacobsen (1850-1921) attest to the popularity of subject matter related to New Jersey’s proximity to the ocean.

During the middle of the nineteenth century, after New Jersey artists had the opportunity to participate in the activities of the Art-Unions in New York and Philadelphia, the popularity of those organizations led to the 1850 establishment in Newark of the New Jersey Art-Union. Paintings were selected for annual prize drawings, including works by landscape painters William Mason Brown (1828-1898) and Jasper Francis Cropsey (18231900). Other selected paintings generally featured still life, genre, and history, and since prints made after them were distributed to all Art-Union members, those subjects had a positive influence on the development of taste for American themes. But the life of that organization was short; following the demise of the New York Art-Union due to a perceived violation of state lottery laws, its Newark counterpart was disbanded in 1853.

During the nineteenth century, still life, animal, genre, and history painting also flourished in New Jersey. The fruit paintings of Hoboken’s Paul Lacroix (fl. 1831-1870); the animal portraits of Susan Waters (1823-1900) of Bordentown; the flower paintings of Paul de Longpre (1851-1911), who lived for a time in Short Hills; and the best-known resident still-life painter, John Frederick Peto (1814-1907) of Island Heights, attest to a great interest in these subjects. Genre and history painters, such as Karl Witkowski (1860-1910), William Tylee Ranney (1813-1857), Lilly Martin Spencer, Robert Walter Weir (1803-1889), and the important Civil War artist, Julian Scott (18461901), also lived and worked in the state. Religious painting in nineteenth-century New Jersey was represented in the work of Rembrandt Lockwood (1815-after 1889) and William Page (1811-1885).

Just after the turn of the twentieth century, New Jersey art schools and organizations began to flourish, particularly in Newark. And before World War I, both the Newark and the Montclair museums opened to the public, due to the efforts of patrons and collectors such as William T. Evans and Louis Bamberger. Some New Jersey artists began to take leading roles in the development of newer art historical movements. Born in Woodstown, Everett Shinn (1876-1953) was a prominent member of the Ashcan school, led by the artist Robert Henri (1865-1929), a style emphasizing contemporary urban realism. In 1911, Shinn was responsible for the Trenton City Hall murals. George Bellows (1882-1925), who painted in a similar style, also depicted polo scenes that he observed in 1910 on a visit to Lakewood. Guy Pene Du Bois (1884-1958), a former student of Henri’s who became a writer as well as a realist painter, lived in Nutley.

With the coming of the Great Depression, the New Deal spawned the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to help unemployed artists create easel paintings as well as mural projects for public buildings. One of the most important examples produced in New Jersey was the Newark Airport Aviation murals by the Armenian-born Arshile Gorky (1904-1948); unfortunately these works disappeared during World War II and are known today only through photographs. Other commissioned WPA paintings include those of the renowned social realist, Ben Shahn (1898-1969), who lived and worked in the Jersey Homesteads (renamed Roosevelt after the president’s death in 1945) where, in 1937, he completed the extant monumental mural in a local elementary school depicting the history of the Jewish flight from oppression and search for better working conditions in the New World. Adolf Konrad (b. 1915) also worked under the auspices of the WPA; and for the rest of the twentieth century, this "painter laureate of Newark” has continued to paint in a highly subjective form of realism.

Before World War II, New Jersey’s artists remained more interested in realism than in newer art movements, including impressionism, precisionism, and cubism; this tendency was evident in the inventory of the major prewar Newark gallery, Rabin and Kreuger. Naturally, there were exceptions, for example, Van Dearing Perrine (1869-1955), an impressionist, who concentrated on scenes of the Palisades, and Stuart Davis (1892-1964), who developed an American form of cubism. But realism dominated the work of many artists including George Overbury "Pop" Hart (18681933), Walt Kuhn (1877-1949), and one of the most significant of all New Jersey artists, John Marin (1870-1953), who developed his own form of expressionism mixed with realism in several scenes related to his hometown of Weehawkin. After World War II, as the center of the art world essentially shifted from Paris to New York, New Jersey artists certainly became aware of the newest trends, but for many years, realism continued to be favored over abstract expressionism and other modern art movements. Ben Shahn lived until 1969, continuing his social realist work, and his Roosevelt neighbor, Jacob Landau (1917-2001), continued to portray controversial scenes of catas-trophies and injustice. Gregario Prestopino (1907-1984), also a resident of Roosevelt, carried on his relationship with the Ashcan school paintings until quite late into the twentieth century. At the same time, in the work of the most important husband-and-wife artistic team in the history of New Jersey, Elsie Driggs (1898-1992) andLeeGatch (1902-1968), Driggs developed a style heavily influenced by the modernism of the precisionists, creators of an American form of cubism, while Gatch’s work evolved over time into a form of abstract expressionism.

Other contemporary New Jersey artists have either absorbed the newest art movements or paralleled their development. For example, Harry Devlin (1918-2002), of Mountainside, a writer and architectural historian as well as an artist, produced highly successful architectural compositions exhibiting the strong influence of contemporary photorealism; George Brecht (b. 1926), formerly of New Brunswick, is considered the father of conceptional and interactive art; Richard Anuszkiewicz (b. 1930), of Englewood, after moving away from the abandon of abstract expressionism, has created his own form of "scientific art” containing blocks of colors, organization, and symmetry; and Lucas Samaras (b. 1936), formerly of West New York, has created a radical means of expression by evoking various states of mind through the art of assemblage.

Arthur Kill. Arthur Kill is a fifteen-mile-long tidal strait that separates Staten Island from northern New Jersey. The kill connects with the Kill van Kull and Newark Bay to the north and with Raritan Bay in the south. The Arthur Kill receives tidal water from both the north and the south, resulting in a long flushing time of about two weeks. It is part of the New York-New Jersey harbor estuary, a series of connecting tidal waterways that receives freshwater drainage from a 16,290-square-mile area. Its banks are heavily populated and highly industrialized, and it is a major shipping lane.

The Arthur Kill was heavily impacted in the 1960s by low oxygen levels due to the dumping of raw sewage, and still has relatively high levels of heavy metals such as mercury, zinc, cadmium, and lead. In January 1990, 567,000 gallons of number 2 fuel oil leaked into the kill from an underwater pipe at the Exxon Bayway refinery. This created a major hazard for invertebrate and fish communities, killing 20 percent of the salt marsh vegetation and many fish and fiddler crabs, and impacting the herons, egrets, raccoons, and other animals that fed on fish and invertebrates. Some species, such as snowy egrets, suffered lowered reproductive success for several years following the spill.

The Arthur Kill supports a variety of ecosystems, including tidal mudflats, tidal creeks, and salt marshes that grade into uplands supporting shrubs and trees. Much of the kill shoreline is lined with bulkheads and riprap, but about 55 percent of the shoreline is natural mudflats and marshes. The Arthur Kill supports a rich community of fiddler crabs, ribbed mussels, snails, and a diversity of other invertebrates, and a diverse fish community of resident and seasonal migrant species. The salt marshes, composed of cordgrass and salt hay, provide primary productivity, nutrient cycling, and habitat, as well as supporting nesting marsh hawks, ducks, blackbirds, and rails. The marshes and the mudflats provide prime foraging areas for herons, egrets, and ibises that nest on Prall’s Island and Isle of Meadows. These islands have traditionally housed some of the largest heronries anywhere in New York and New Jersey. Gulls and double-crested cormorants also nest on these islands and abandoned piers. Many hawks overwinter in the Arthur Kill. The Arthur Kill is also important for local residents who fish, crab, boat, and engage in other recreation on the water and in adjacent parks and uplands.

Washed-up debris on the shore of Prall’s Island in the Arthur Kill.

Art PRIDE New Jersey. Incorporated in 1986, Art PRIDE New Jersey is a nonprofit organization that promotes and supports arts groups throughout the state. ArtPRIDE’s over two hundred members helped increase state arts funding from $3 million in fiscal year 1984 to a present appropriation of $18 million in fiscal year 2003. In 2000, ArtPRIDE successfully advocated for passage of the New Jersey Cultural Trust Act, which will, as stated in the act, "help build endowments, create institutional stability, and fund capital projects.” The organization hosts the annual ArtPRIDE Congress and keeps the arts on the public policy agenda by providing information and research to federal, state, and local elected officials.

Asbury Park. 1.4-square-mile city in Monmouth County. New York City brush manufacturer James Bradley purchased five hundred acres from Ocean Township in 1871 and named the community for the first bishop of the Methodist Church in America. He incorporated the town, bordered by Deal Lake to the north and Wesley Lake to the south, in 1874 and guided its development as a resort for physical and mental rejuvenation until his death in 1921. Bradley fulfilled his primary intent—to design a white, middle-class resort with gardens, parks, and lakes— with the goal of having the entire beachfront and boardwalk owned by the city rather than private citizens. The city’s specialized districts included hotels, business, amusement, and the cottage community—an early experiment in urban planning. A temperance resort more like Ocean Grove than the gamblers’ haven of Long Branch, the town also catered to the more worldly pursuits of billiards, bowling, and dancing. Railroad service began in 1875, bringing thousands of people to the summer resort each day. Starting in 1873, the town supported several daily, weekly, monthly, and summer-only newspapers with particular and distinct foci—temperance, religion, African Americans, labor, and society. Asbury Park operated the first trolleys in the state in 1877 and constructed the first comprehensive citywide sewer system on the New Jersey coast in 1881.

Until 1970 Asbury Park was a popular family resort, with promenades, piers, water pageants, band concerts, children’s carnivals, and baby parades. Hundreds of hotels, motels, cottages, and guesthouses supported the burgeoning tourist trade. Day-trippers and group excursionists arrived by train from Philadelphia and New York. Visitors and residents could spend the day lounging on the beach, then dress up to view exclusive-engagement films at one of the five palatial movie theaters, and cap off the evening with a stroll on the boardwalk. Children enjoyed pony rides on the beach and swan-shaped pad-dleboat rides on Wesley Lake. The Cookman Avenue business district attracted shoppers from towns throughout the county. In the mid-1960s a fire from a dropped cigarette destroyed the boardwalk and most of the rides and concessions; owners rebuilt everything in time for the following season. Asbury Park earned honorable mention as an All-American City in 1961 and 1963.

In 2000, the population of 16,930 was 25 percent white, 62 percent black, and 16 percent Hispanic. The median household income in 2000 was $23,081.

Asbury Park postcard. By the late nineteenth century, a distinct and growing African American and working-class district had developed across the railroad tracks in West Park, where residents were confined to segregated housing amid the laundries and auto repair shops. They were welcome as hotel staff but were excluded from the resort’s amusement district and beach. West Park grew as a shadow resort, fostering recreational activities deemed morally unsuitable for the middle-class vacationers. A July 1970 riot damaged and destroyed much of the downtown business district and injured almost two hundred civilians and police. Longtime residents believe the riot sparked the mass exodus of businesses and homeowners. Hotels not boarded up or demolished were converted to apartments for senior citizens and the mentally ill, who had been discharged from Marlboro State Hospital to community outpatient care. The once-vibrant boardwalk, anchored by Convention Hall and the Paramount Theatre on the north and by the Casino and Palace Amusements on the south, awaits either destruction by the next hurricane or redevelopment of the beachfront with state or private funds. Gone are the rides and arcades; only a few scattered, boarded-up buildings remain. While the north end valiantly hangs on with the restored Paramount Theatre and Berkeley-Carteret Hotel, the south end of the boardwalk has fallen into disrepair. Today Asbury Park is seeking to recover. One hopeful sign is that Palace Amusements—the former home of the Aurora Ferris wheel—has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Asbury Park Press. The second-largest newspaper in the state, the Asbury Park Press circulates primarily in Monmouth and Ocean counties. It was founded as a weekly newspaper on July 10, 1879, by Dr. Hugh S. Kinmonth, above his pharmacy on Cookman Avenue in Asbury Park. That first edition of theShorePress, as itwas called, sold250 copies. Kinmonth sold the paper sixteen years later to his nephew, J. Lyle Kinmonth. The younger Kinmonth transformed the paper into a daily and renamed it the Daily Press. He also introduced a Sunday newspaper, a popular innovation in the late nineteenth century. Kinmonth relocated the newspaper operation to a new building on Mattison Avenue in 1912, but four years later the building was destroyed by fire. He replaced the structure with a five-story building and continued to expand his news operation. When Kinmonth died in 1945, ownership of the newspaper passed to its senior executives, Wayne D. McMurray and Ernest W. Lass. McMurray was at the helm for twenty-nine years and Lass for thirty-five. When McMurray died in 1974, he willed his ownership in the newspaper to Jules L. Plangere, Jr., then secretary and general manager.When Lass died in 1980, his son, E. Donald Lass, became president and editor. The newspaper left Asbury Park in 1985 and relocated to new headquarters in Neptune, although it retained the Shore resort’s name on its masthead.

In 1995 the privately owned New Jersey Press, the holding company for the Asbury Park Press, expanded its influence with the purchase of the Home News and the News Tribune, two Middlesex County newspapers. Those papers were combined to form the Home News and Tribune (later shortened simply to the Home News Tribune), which began publishing on October 9,1995.

Ashbridge, Elizabeth (b. 1713; d. May 16, 1755). Preacher and writer. Born in Cheshire, England, Elizabeth Ash bridge was the only child of Thomas and Mary Sampson. She eloped at fourteen with a stocking weaver who died three months later. Estranged from her parents, she stayed for a time with relatives in Ireland, one of whom was a Quaker. In 1732 she decided to immigrate to New York. Forced into indenture by the ship’s captain, for three years she served a cruel master, paying off the last year of her contract in 1735. In 1736 she married a schoolteacher named Sullivan, and the two lived in New Jersey, where most of her later autobiographical narrative takes place. Her husband opposed her 1738 conversion to Quakerism, and in an attempt to isolate her from the Quaker community, Sullivan instigated a number of moves in the ensuing years, to Freehold in East Jersey, Bordentown, and Mount Holly. In 1740 Sullivan died, and six years later Elizabeth married Aaron Ash bridge, a Quaker from Chester County, Pennsylvania, and was soon an influential preacher in Quaker circles. In 1753 she was granted permission to travel back to Europe to pursue her ministry. She fell ill and died in Ireland. Ash bridge is best known for her autobiography, Some Account of the Fore Part of the Life of Elizabeth Ash bridge… Written by Her Own Hand Many Years Ago, which details her spiritual and temporal struggles.