Appalachian Mountains. The remains of an ancient mountain belt in the eastern United States that resulted from the collision of lithospheric plates at the close of the Paleozoic era about 250 million years ago. The Appalachian system extends from northern Georgia and Alabama northeast to New England and the Canadian Maritimes. In north-central New Jersey, the Appalachians are represented by three northeast-southwest trending physiographic provinces, or land-form regions (the Ridge and Valley, the Highlands, and the Piedmont) that together cover 40 percent of the state. Kittatinny Mountain, a prominent ridge of the Appalachians, extends thirty-five miles from the New York border to the Delaware Water Gap. The highest elevation in New Jersey (High Point at 1,803 feet) is located on Kittatinny Mountain.

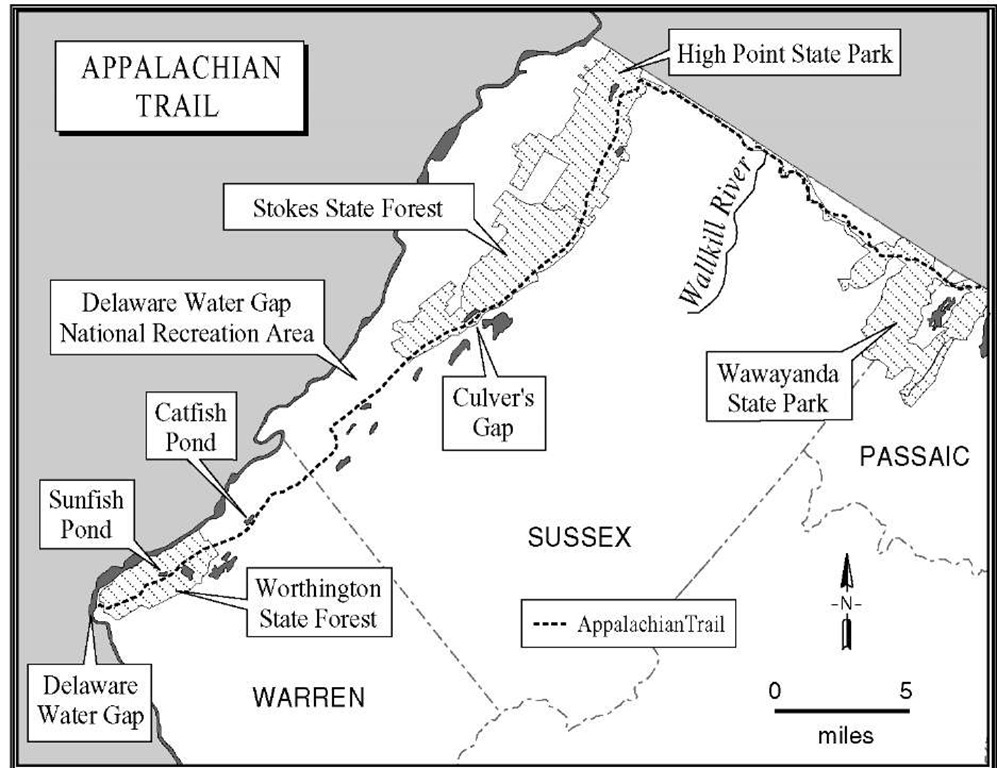

Appalachian Trail. The Appalachian Trail is a footpath extending more than 2,i00 miles from Springer Mountain, Georgia, to Mount Katahdin, Maine. A stretch of 73.6 miles passes through Warren, Sussex, and Pas-saic counties in northwestern New Jersey.

The idea for the Appalachian Trail originated in 1921 at an informal gathering at Hudson Guild Farm in Sussex County, near Lake Hopatcong. The meeting resulted in an essay by forester and planner Benton MacKaye advocating a linear Appalachian Mountain park as a tool for regional planning. The portion of the Appalachian Trail through New York and New Jersey was the first to be completed, c. 1928, through the efforts of Raymond H. Torrey and the New York-New Jersey Trail Conference.

From the south, the Appalachian Trail enters New Jersey via the Delaware Water Gap, ascending Mount Tammany and Kittatinny Ridge, which it follows for 45 miles. In Worthington State Forest and the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, the trail passes Sunfish Pond, Raccoon Ridge, and Catfish Fire Tower before entering Stokes State Forest and ascending Culver’s Gap. From there it passes Culver Fire Tower and approaches Sunrise Mountain, where a large pavilion was constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1937-1938. Entering High Point State Park, it passes near High Point Monument before leaving Kittatinny Ridge to go through the Kittatinny Valley. Traversing woods, fields, and swamps, it crosses the Wallkill River before ascending PochuckMountain and passing through the Vernon Valley, where a 150-foot suspension bridge and 3,ooo-foot boardwalk were constructed across the Pochuck River floodplain in the late 1990s. Ascending 800-foot Wawayanda Mountain, the Appalachian Trail enters the Highlands, passing through Wawayanda State Park and entering New York State on Bearfort Mountain.

The Appalachian Trail was constructed and is primarily maintained by volunteers from local hiking organizations. Seven shelters for backpackers have been constructed along the New Jersey section of the Appalachian Trail, spaced an average of ten miles apart; there is also one campground. Since the 1970s, state and federal authorities have acquired land to buffer the Appalachian Trail from adjacent development, particularly in the Vernon and Wallkill valleys. The portion of trail between Wawayanda Mountain and Kittatinny Ridge was completely relocated away from highways onto a protected corridor by the late 1980s, and numerous bridges and sections of boardwalk were constructed. Several thousand backpackers hiking some or all of the Appalachian Trail pass through New Jersey annually.

Appel Farm Arts and Music Center. Founded in i960 and located on a 176-acre farm, Appel Farm Arts and Music Center is a nonprofit regional arts center located in Upper Pittsgrove Township. The center’s programs include a residential summer arts camp for children ages nine through seventeen, a nationally renowned folk festival held on the first Saturday in June, a professional concert series, community and school arts outreach, and a conference center. Ap-pel Farm serves over fifty thousand people annually.

Applejack. A liquor made from apples, applejack is also known as apple brandy, apple whiskey, cider spirits, or "Jersey Lightning.” Applejack has mainly been produced by distilling hard cider. Because of the adaptability of the imported trees and the ease of manufacturing cider, which ferments naturally, apples were the primary source of alcohol in early America. It was safer to drink than water, and was therefore consumed in great quantities. In New Jersey, known for the quality of its apples, applejack was already being produced by the late seventeenth century, and in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries "Newark cider” was exported to much of the country. Stills that rendered the mildly alcoholic cider into more potent and portable applejack were widespread in the state as early as the mid-eighteenth century. Most large farms distilled small quantities for household consumption, but by the early nineteenth century commercial distillers were using huge cider stills with capacities of over a thousand gallons; in i834 there were 388 distilleries in the state. New Jersey never had a monopoly on applejack production but, as the name "Jersey Lightning” suggests, it was closely identified with the liquor. During Prohibition, bootleg Jersey applejack was popular, in part because it was thought to be safer to drink than other forms of moonshine. Legitimate distillers rebounded somewhat after the i933 repeal, but rising apple prices and changes in American drinking habits proved fatal to almost all of them. The sole survivor, Laird and Company of Scobeyville, is the oldest operating distillery in the United States; although its apples are no longer grown in New Jersey, the company continues to produce and market applejack, in addition to bottling and importing less traditional spirits.

Apollo Muses. Apollo Muses supports and presents arts programs in central New Jersey. The organization was founded in i984 by Eric Gustafson of Peapack-Gladstone to help young professional artists find opportunities to perform their music, dance, theater, and poetry, as well as to show their paintings and sculpture. The organization also arranges for distinguished veteran artists to share their experiences. The organization has supported programs in New Jersey schools, libraries, and museums, as well as at Carnegie Hall, New York University, and the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center in New York.

Aquifers. Aquifers are water-bearing geological formations that can store and transmit substantial amounts of groundwater to wells and springs. The formations can be either unconsolidated (e.g., Kirkwood-Cohansey Formation in the Coastal Plain of southern New Jersey) or consolidated (e.g., Stockton Formation in central New Jersey). The most productive aquifers in the state are the sandy formations in the Coastal Plain (e.g., Potomac-Raritan-Magothy) and the sand and gravel deposits in buried glacial valleys in northern New Jersey (e.g., Ramapo River Valley in Bergen County). The least productive aquifers are the diabase and argillite formations in central New Jersey (e.g., Sourland Mountains) that are poorly fractured, with very limited capability to transmit water.

Arbitration. In the last decade, there has been a huge increase in the number and type of disputes submitted to arbitration. The benefits of arbitration are well known: this process is less costly, less time-consuming, and probably more equitable than is adjudication.

Under the New Jersey Arbitration Act, individuals must submit to court-annexed or mandatory arbitration if they are filing a civil claim alleging personal injury, and if the amount of monetary damages sought is less than either $15,000 for a claim arising from an automobile accident or $20,000 for injuries arising from other claims. New Jersey is one of only six states that mandate arbitration, and there are a number of facets that are unique to the state’s arbitration procedure, such as the requirement that the parties exempt themselves from arbitration if they seek medical expenses in excess of $4,500 or if the case involves novel or complex features. Under state law, parties have a right to appeal their arbitration awards in court, and there is little penalty for those who have not participated in the arbitration process in good faith. An award arising from court-annexed arbitration can be vacated only if there is evidence that the arbitrators have engaged in fraud, corruption, or other wrongdoing.

In addition to mandatory arbitration, parties can agree to submit to arbitration as part of a contract. For a court to uphold a voluntary arbitration agreement, there must be clear and unambiguous evidence of the parties’ intent to arbitrate. The contract must state that arbitration will proceed in accordance with all federal and state statutory and common law, and that all remedies and rights established under these laws will be recognized. At present, some state agencies, including the New Jersey Division on Civil Rights, are seeking to expand the use of mediation, which has less formal procedures and may provide greater opportunities for participation by the disputants.

Archaeology. New Jersey’s first archaeological excavations occurred during the mid-nineteenth century and were carried out by avocational archaeologists coming from a natural science tradition. With few exceptions, these early archaeologists studied the state’s aboriginal past.

Charles Conrad Abbott (1843-1919), generally regarded as the state’s first archaeologist, conducted pioneering excavations on his family’s property, Three Beeches, near Trenton. Abbott’s interest focused on New Jersey’s Native American inhabitants. In his excavations, he discovered ancient stone tools, which he termed "paleoliths.” These artifacts, found in gravel deposits along the Delaware River, appeared similar to stone tools found in Pleistocene deposits in Europe. Citing these similarities, Abbott argued vociferously that human occupation of the New World dated back some forty thousand years.

Abbott’s theories generated considerable interest in New Jersey’s prehistory. Under the sponsorship of the Peabody Museum of Harvard University (1889-1891,1893-1895) and the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893-1895), Abbott’s protege, Ernest Volk, excavated sites in and around Trenton, searching for traces of early human presence. Although Volk discovered extensive archaeological evidence for prehistoric occupation of the Delaware Valley, his work failed to support Abbott’s claims about the earliest arrival of humans in the New World.

Ultimately, Abbott’s theories were disproved. Nonetheless, he was an important figure in the development of North American archaeology. The Abbott Farm, his family homestead, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976. It is one of two archaeological sites in New Jersey to be accorded this honor, and it remains one of the most important sites in the mid-Atlantic region.

In the late nineteenth century, researchers from the Smithsonian Institution carried out other pioneering excavations in New Jersey. Charles Rau investigated Native American shell heaps near Keyport, while Frank Hamilton Cushing examined the Tuckerton Shell Mound.

In 1912 the New Jersey Geological Survey, working in cooperation with the Department of Anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History, began the state’s first formal archaeological survey. Archaeologists Alanson Skinner, Leslie Spier, and Max Schrabisch directed the fieldwork. A preliminary report of the survey, published in 1913, listed roughly one thousand sites: camps, burial grounds, rock shelters, and shell heaps. Schrabisch and Spier continued the survey in 1913, with Schra-bisch focusing on Sussex County, where he located numerous rock shelters. Spier investigated sites in and around Plainfield in Union County, as well as portions of Gloucester and Salem counties. In 1914 and 1915 Schrabisch carried out further fieldwork in Warren and Hunterdon counties. The results of this survey were published in three reports by the New Jersey Geological Survey. Later, working on his own, Schrabisch investigated Native American sites in the northern portion of the state and adjacent sections of Pennsylvania and New York. Although much of this early work was undertaken without a clear understanding of how long Native Americans had inhabited New Jersey and focused more on artifacts than context, these studies remain valuable sources of information about New Jersey’s prehistoric past.

During the 1930s, Dorothy Cross (Jensen), a professor of anthropology at Hunter College, supervised the New Jersey Indian Site Survey, a project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) designed to employ out-of-work laborers. Between 1936 and 1938, Cross identified numerous sites, and she later reported her findings in two lavish volumes published with the assistance of the New Jersey State Museum and the Archaeological Society of New Jersey. The first volume (1941) provides an overview of New Jersey prehistory and detailed descriptions of thirty-nine sites investigated by the survey. The second volume (1956) focuses on Cross’s excavations at the Abbott Farm.

Until the 1930s, historic sites in New Jersey received less archaeological attention than prehistoric ones. (Notable exceptions were Charles Conrad Abbott’s investigation of a seventeenth-century Dutch site in Burlington County in the 1890s and Max Schrabisch’s testing at a Revolutionary War site at Pluckemin in 1916 and 1917.) Crews of Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers under the direction of National Park Service archaeologists carried out extensive formal excavations at Morristown National Historical Park, identifying the remains of soldiers’ huts, earthworks, and other structures associated with the Revolutionary War.

In the second half of the twentieth century Herbert Kraft of Seton Hall University, following in the footsteps of Abbott and Cross, studied numerous Native American sites in the upper Delaware Valley. Excavations probed Harry’s Farm, the Pahaquarra Site, and the Minisink Site (also a National Historical Landmark). The latter, located along the Delaware River in Sussex County, New Jersey, and Pike County, Pennsylvania, has yielded a wealth of information on New Jersey’s Native Americans in the late prehistoric and early historic periods. Kraft’s excavations at these sites set a new standard for archaeology in New Jersey. His book The Lenape: Archaeology, History, and Ethnography (1986) remains the definitive summary of New Jersey’s prehistory.

Since the 1970s the amount of archaeological research in the state, at both historic and prehistoric sites, has grown considerably. Much of this work was spurred by federal legislation enacted in the 1960s and 1970s. As a result, extensive excavations were carried out in Paterson, New Brunswick (including nearby Raritan Landing), Trenton, and along the Morris Canal and the Delaware and Raritan Canal. Highway construction in the area around Trenton also led to a massive reinvestigation of the Abbott Farm site.

Institutions holding major archaeological collections from New Jersey include the New Jersey State Museum, the Seton Hall University Museum, the University of Pennsylvania Museum, the Peabody Museum at Harvard University, and the Smithsonian Institution. The State Museum maintains a database of registered sites in the state, and the Historic Preservation Office in the Department of Environmental Protection serves as a repository for archaeological reports.

The Archaeological Society of New Jersey, the only statewide organization dedicated to studying New Jersey’s archaeological heritage, was founded in 1931. Active today, it continues to publish its annual Bulletin.

During the twentieth century, archaeology in New Jersey developed from a dilettante’s passion to a scientific endeavor often mandated by federal and state regulations. Ongoing archaeological studies are reshaping our understanding of New Jersey’s Native American heritage and historic development.

Architecture. Because of the diverse nature of its settlement, New Jersey’s seventeenth- and eighteenth-century architecture is complex and varied, with forms and materials related to location and ethnicity. Initially settled by Dutch, Swedes, and Finns, New Jersey after 1664 passed into the hands of English proprietors, many of whom were Quakers. They offered religious freedom, which attracted English and Scots-Irish immigrants of several religious persuasions from various parts of Great Britain. During the latter part of the eighteenth century, Germans settled in the northwestern part of the state. These groups brought differing vernacular traditions, which they adapted to the New World. Their buildings vary in materials and plan.

Early descriptions of New Jersey houses mention several building materials, including brick, stone, and vertical planking, undoubtedly over a wooden frame. Log construction also was used from the late seventeenth through the mid-eighteenth century, although few examples survive. It was a handy and inexpensive building material, adopted by almost all groups, although probably brought to this country by settlers from northern Europe. In southwestern New Jersey the log-building techniques are thought to have been introduced by the Finns and Swedes. The best known of the surviving examples is the one-room Nothnagel Cabin in Gibbstown, Gloucester County, which accords with a seventeenth-century description of a Swedish cabin as having a corner fireplace. Germans coming into the northern Delaware Valley from Pennsylvania are believed to have introduced log construction to the northwestern counties. Often, as in the two-story Seigle Homestead in Warren County, the logs have been masked by clapboarding.

Congregationalists moved down from New England into the Newark area, bringing a medieval tradition of heavy timber framing. In this type of construction, posts and beams with diagonal braces form one or more "boxes,” which then are sheathed in clapboard. This method spread through the northeastern part of the state. Again, few examples survive in pristine condition. One is the house built circa 1690 on the William Robinson Plantation in Clark. Another is a section of Rockingham, a house along the Millstone River near Kingston. Several buildings in Cape May County, which again was settled by New Englanders, also are framed in this manner.

Brick came into use quite early in the southwest, where William Penn urged the early Quaker settlers to use this fireproof material. What he might not have anticipated is that they would develop a distinctive, highly decorative form of brick patterning. This features a bond known as Flemish checker, combining black or blue-gray glazed headers (the short end of the brick) with red stretchers. Gable ends are ornamented with dates and the builder’s initials and sometimes with elaborate patterns of diamonds, zigzags, or flowers.

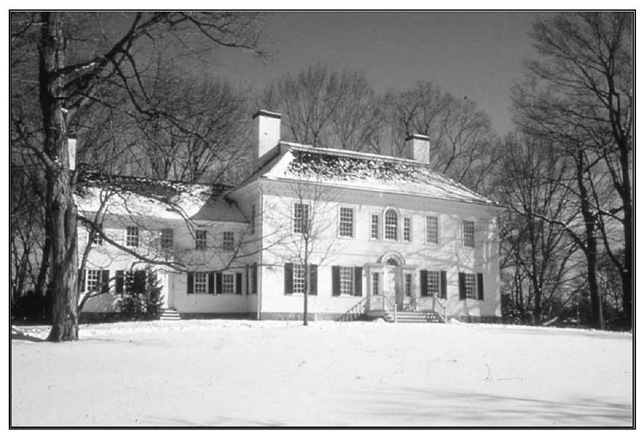

The Ford Mansion in Morristown was Gen. George Washington’s headquarters from December 1779 through June 1780.

The Dutch entered New Jersey in two streams. One, from the Hudson River Valley, came from a masonry tradition, generally expressed in stone, as in numerous houses in Bergen County. The other group emigrated from Long Island, where frame was prevalent. In contrast to the English braced frame, Dutch construction employed a series of bents, with each beam resting directly on posts.

Building vernacular structures with traditional plans, construction methods, and materials continued well into the nineteenth century. But contemporaneous with these were a series of high styles. The earliest of these styles, the Georgian or Anglo-Palladian, depended on symmetry, balance, and rational geometry. The most common house form became two-and-a-half-stories high and one or two rooms deep, with a center stair hall flanked by rooms of equal size to either side. Smaller houses might utilize two-thirds of this plan, that is, a side hall, usually with two rooms to one side. The brick Trent House, circa 1719, in Trenton is a remarkable example of early Georgian design. Another house museum in the Georgian style is the mid-eighteenth-century Dey Mansion in Wayne, which mingles Dutch and English influences. One of the finest Anglo-Palladian houses executed in wood is the Ford Mansion (1772-1774) in Morristown, now part of the National Historical Park. Its handsome Palladian doorway and the matching window on the second floor are derived from an English pattern book.

With this more formal style, the influences of New York and Philadelphia overrode that of traditional cultural differences. The Trent House, for example, is clearly related to James Logan’s Stenton in Germantown, on the outskirts of Philadelphia. The College of New Jersey in Princeton turned to a Philadelphia builder-architect, Robert Smith, for its main building, Nassau Hall, and its president’s house (1754-1756). In contrast, in Perth Amboy the provincial council chose a New York builder-architect, John Edward Pryor, for the Proprietary House. Most builders, however, remain anonymous, like the designer of the Ford Mansion, although he clearly had access to English pattern books by Batty Langley. But, in fact, most of New Jersey’s Anglo-Palladian buildings are simplified versions of high-style prototypes. Like the Conover House in Freehold or the Burrowes House in Matawan, they merely feature Anglo-Palladian massing and center- or side-hall plans with rather plain decorative details such as paneling and classically derived decorative motifs. Regional preferences for materials persisted—wood in East Jersey and masonry in West Jersey.

In the post-Revolutionary, or Federal, period, basic design principles of symmetry and axial organization continued, but walls often appeared as a thin membrane, openings became larger, and detailing more delicate. Decoration remained based on motifs from classical antiquity. Now, however, it was influenced by the more delicate forms unearthed in late eighteenth-century excavations at Herculaneum and Pompeii. The Morris County Courthouse (1827), for example, is basically an Anglo-Palladian building, but with attenuated pilasters and blind arches over the windows. Again, few New Jersey design sources can be identified and dependence on adjacent metropolitan centers remained strong. Several buildings are direct echoes of Philadelphia prototypes. The transitional Georgian/Federal Burlington County Courthouse (1796) in Mount Holly is a copy of Congress Hall in Philadelphia; Merino Hill (1810) in Wrightsville, Monmouth County, is based on the Bingham House, also in Philadelphia; the Presbyterian Church (17921795) in Bridgeton, Cumberland County, echoes Saint Peter’s in the same city. Other designs were based on pattern books. A number of widely scattered buildings derive from designs published by the New England builder-architect Asher Benjamin. Examples include the Edward Sharp House (1812) in Camden City, the Castner Parsonage (18151819) in Asbury, Warren County, and Fenwick Manor (1827) in New Lisbon, Burlington County.

Although classical motifs, such as pediments and columns, had formed the decorative vocabulary of both Georgian and Federal architecture, they had not been derived from antique models. In the early years of the new United States, however, Rome was looked at as a font of republicanism and Greece as the birthplace of democracy.

Because of this, their architecture was viewed as something to be emulated. Full-blown Greek Revival never was as prominent in New Jersey as in New York State, Vermont, and Ohio. Nevertheless, some important examples survive, although others have been demolished. Mercer and Middlesex counties erected ambitious Greek Revival courthouse complexes in 1838 and 1839. The former was by Princeton builder-architect Charles Steadman, the latter by New Brunswick native Minard Lafever, a cousin of the New York architect of the same name. Although these failed to survive growth in central New Jersey, two more rural temple-front courthouses did better, the Hunterdon County Courthouse in Flemington (1828; perhaps most famous as the site of the Lindbergh kidnapping trial) and the Sussex County Courthouse in Newton (1847).

A few houses with colossal colonnaded porticoes were built, such as Mead Hall (1833), now the main building of Drew University in Madison, Morris County, and Drumthwacket (1834-1836) in Princeton, now the governor’s mansion. Most dwellings expressed the style more modestly. The Nassau Street Presbyterian Church (1836) in Princeton is an early example of a temple-form in antis facade, designed by Thomas U. Walter, and became a prototype for several churches built in the 1840s. Flemington, in Hunterdon County, has a particularly rich group of impressive Greek Revival buildings designed by a local builder-architect, Mahlon Fisher. Among them are Fisher’s own house (1845-1846) and the Reading-Large House (1847), the latter with the extravagant detailing typical of later phases of the style. Again, however, as in earlier periods, the vast majority of buildings are vernacular, distinguished as Greek Revival only by such features as attic windows or small porticoes with classical columns.

The A.W. Demarest House, c. 1880-1900, in Upper Saddle River is a significant example of Queen Anne style architecture.

To look at ancient Rome and classical Greece for inspiration was a romantic notion. So although the Greek Revival continued the classical tradition of Anglo-Palladianism, it also was the first of the romantic revivals that dominated in the pre-Civil War period. The country’s first major Italianate villa, Riverside (1838-1839; demolished), was built in Burlington City. Three later examples by its architect, John Notman, survive in Princeton. The Italianate became a popular style for buildings of all types. Many houses were based on pattern books; once again location in relation to New York and Philadelphia to some extent determines their source. Thus Freehold, in Monmouth County, has several Italianate houses derived from the influential publications of A. J. Downing, a landscape architect based in Newburgh, New York, while houses drawn from a Philadelphia pattern book by John Riddell are largely confined to Burlington City. By this time, however, widespread dissemination of publications began to break down regional differences; examples from Philadelphian Samuel Sloan’s books are scattered throughout the state. Not all Italianate buildings are freestanding. Jersey City and Hoboken have streets of well-preserved brownstones, emulating the row houses of New York City. The treatment of their doorways, windows, and heavy cornices derives from the Italian palazzo.

The early Gothic Revival is also well represented in domestic and church architecture. Important examples include the Nicholls Cottage, the boyhood home of Charles Follen McKim of McKim, Mead, and White, and the gatehouse in Llewellyn Park in West Orange. These were designed by A. J. Davis, who, in collaboration with developer Llewellyn S. Haskell, also laid out this early planned, romantic suburb (1857). In Ho-Ho-Kus, Bergen County, New York architect William Ranlett transformed an early Dutch stone house, known as The Hermitage, into a fanciful Gothic cottage (c. 1850). Victorians were concerned with suitability. Gothic, because of its association with English and French medieval religion, was considered particularly appropriate for churches. The ecclesiological movement, which called for a return to medieval rites and medieval architecture, produced a spate of important Episcopal churches at midcentury. New Jersey has examples by New Yorkers Richard Upjohn and Frank Wills and Philadelphian John Notman.

One of the less common of the romantic styles, because of its associations with death and entombment, was the Egyptian Revival. Philadelphia architect John Haviland designed two public buildings in the style. One, Trenton State Penitentiary (1836), was the first major Egyptian Revival building in the United States, and had worldwide influence as a model for prisons. The other was the Essex County Courthouse (1838; demolished).

In the decades from the end of the Civil War to the end of World War II, the population of New Jersey almost trebled, and construction of buildings expanded accordingly. A popular post-Civil War style was the French Second Empire, distinguished by the mansard roof. Although this had relatively little impact on major projects, builders erected many dwellings, again often based on pattern books, in all parts of the state. The form of the Gothic Revival known as Carpenter’s Gothic enjoyed special popularity at the Shore. Significant concentrations of houses with elaborate jigsaw trim survive in Ocean Grove and Cape May.

More formal masonry High Victorian Gothic appeared in such buildings as William A. Potter’s Chancellor Green Library (1873) at Princeton University. The Jersey Shore was also a fertile ground for the Stick and Shingle styles. Although few examples in the former style remain, the Dr. Emlen Physick House (1879) in Cape May, attributed to Frank Furness, is now a museum. What is generally considered Charles McKim’s first Shingle style house, the Moses Taylor House (1877), is in Elberon.

The last three decades of the nineteenth century and the first three of the twentieth century introduced a plethora of new styles—Queen Anne, Beaux Arts Classical, Renaissance Revival, Romanesque Revival, and Colonial Revival. New Jersey clients often continued to turn to New York and Philadelphia architects. From the former city these included McKim, Mead, and White; Carrere and Hastings; J. Cleveland Cady; John Russell Pope; Delano and Aldrich; Albro and Lindeberg; Cass Gilbert; Bruce Price; and William Lawrence Bottomley. Among the Philadelphians were Cope and Stewardson, Mellor Meigs and Howe, Wilson Eyre, G. W. and W. D. Hewitt, William L. Price, and Day and Klauder. Boston firms that worked in the state included Cram and Ferguson and Peabody and Stearns. At the same time, the architectural profession was becoming established locally. Henry Hudson Holly maintained an office in New York, but many of the designs he published were for New Jersey clients. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, local practitioners flourished, among them Guilbert and Battelle, William E. William, Sr., and W. Halsey Wood in Newark; Arnold Moses of Camden, who designed New Jersey’s senate chamber; William A. Poland in Trenton; and Joy Wheeler Dow, who worked in Millburn and other northern suburbs.

In the early twentieth century, the influence of the Arts and Crafts movement began to be felt. Commuting suburbs burgeoned in this period with bungalows, four-squares, and other house types, frequently based on the publications of Gustav Stickley. Stickley himself developed his country estate, Craftsman Farms (1909-1912) in Parsippany-Troy Hills. Through the twentieth century, New Jersey’s rapidly developing suburbs provided streets lined with Georgian Revival, Dutch Colonial, Tudor, and Mediterranean designs. In the years following World War II, traditional house forms and styles often gave way to split-level and ranch houses.

New Jersey was slow to accept modernism. Nevertheless, the Depression years of the 1930s witnessed construction of some notable Art Deco buildings. The headquarters of Jersey Bell in Newark, completed just before the stock market crash in 1929, was the most prominent of a number of buildings erected in that style by the company. Newark also gained two important transportation terminals in 1935: Penn Station, a late work by the firm of McKim, Mead, and White, and the original terminal at Newark Airport. A monumental, multibuilding Art Deco complex, the Jersey City Medical Center, was under construction through most of the 1930s. William Lescaze designed an International Style office building for the Kimble Glass Factory in Vineland, while Antonin Raymond was the architect for a small Art Moderne office building in Trenton.

The period following World War II saw the gradual emergence of modernism and postmodernism, although much building in New Jersey remains conservative. Examples include four Usonian houses by Frank Lloyd Wright, Bell Laboratories at Holmdel (1962) by Eero Saarinen and Kevin Roche, Louis Kahn’s bathhouses and master plan for the Jewish Community Center (1957-1964) in Trenton, and several buildings by Robert Venturi at Princeton University. One of the best-known architects practicing in New Jersey is Michael Graves, who designed, among other buildings, the environmental pavilion at Liberty State Park in Jersey City and the Ploeck House in Warren Township. Other nationally known New Jersey firms are the Robert Hillier Group and the Grad Partnership.

New Jersey’s early settlers produced a rich variety of vernacular buildings derived from the traditions of several European countries, and thus exhibiting the greatest architectural diversity to be found in the original thirteen colonies. By the eighteenth century, affluent citizens chose high-style architecture. Although prevailing forms were widely disseminated, the historic East Jersey/West Jersey split continued to be expressed, with the former influenced by New York and the latter by Philadelphia. These preferences continued well into the twentieth century, with many patrons choosing architects from the two metropolises. By the end of the nineteenth century, New Jersey was less dependent on out-of-state practitioners, but followed national trends rather than exhibiting identifiable regional characteristics.

Despite the state’s high population density, a surprising number of examples of the architecture of all periods have survived. Some, especially those with strong historical associations, are preserved by the Historic Sites section of the state’s Division of Parks and Forestry. Others are in the hands of local historical societies and other private groups. Still others, far outnumbering those held publicly or by organizations, remain in the hands of private owners. Cities such as Burlington and Salem display rich collections of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century architecture. Other early buildings can be found in still-rural areas, particularly in the southern and northwestern sections of the state. Victorian architecture is well represented along the Shore in towns such as Cape May, Ocean Grove, and Spring Lake. Other fine examples from the second half of the nineteenth century can be found in suburbs developed at that time, such as Maplewood, Montclair, and Millburn-Short Hills. Cities such as Newark exhibit a range of building types dating from the eighteenth century to the present. So do smaller towns, such as Princeton, where both town and gown display a panorama of American architecture, with the university having retained major architects to fulfill its needs from the mid-eighteenth century onward.