Yurok is a Karuk word meaning "downstream" and refers to the tribe’s location relative to the Karuk people. The Yurok referred to themselves as Olekwo’l, or "persons."

Location Traditionally, the Yurok lived in permanent villages along and near the mouth of the Klamath River, in northern California. Today, many live on several small rancherias in Humboldt County.

Population The aboriginal Yurok population was roughly 3,000 (early nineteenth century). In 1990, 1,819 Indians, not all of them Yurok, lived on four Yurok reservations. Other Yurok lived off-reservation. The official Yurok enrollment in 1991 was about 3,500.

Language Yurok is an Algonquian language.

Historical Information

History Some Yurok villages were established as early as the fourteenth century and perhaps earlier. Their first contact with non-natives came with Spanish expeditions around 1775. The first known contact was among Hudson’s Bay Company trappers and traders in 1827. However, the Yurok remained fairly isolated until about 1850, when a seaport was created in Yurok territory to make travel to the gold fields more accessible. The rush of settlers after 1848 led to a wholesale slaughter and dispossession of the Yurok. An 1851 treaty that would have established a large Yurok reservation was defeated by non-Indian interests. Shortly after the first white settlement was founded, Yuroks were working there as bottom-level wage laborers.

President Franklin Pierce established the Klamath River Reservation in Yurok Territory in 1855. Congress authorized the Hoopa Valley Reservation in 1864. In 1891, the Klamath River Reservation was joined to the Hoopa Reservation in an extension now called the Yurok Reservation. This tract of land consisted of 58,168 acres in 1891, but allotment and sale of "surplus" land, primarily to Anglo timber companies, reduced this total to about 6,800 acres. Three communal allotments became the rancherias of Big Lagoon, Trinidad, and Resighini.

From the mid-nineteenth century into the twentieth, many Yuroks worked in salmon canneries. Yuroks formed the Yurok Tribal Organization in the 1930s. Indian Shakerism was introduced in 1927, and some Yuroks joined the Assembly of God in the 1950s and 1960s. In a landmark 1988 case, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to protect sacred sites of Yurok and other Indians from government road building. Also in 1988, the Hoopa-Yurok Settlement Act partly resolved a long-standing dispute over timber revenues and fishing rights.

Religion With other northern California Indians, local Yurok groups practiced the World Renewal religion and the accompanying wealth-displaying white deerskin and jumping dances. Other ceremonies included the brush dance, kick dance, ghost dance, war dance, and peace dance. People who performed religious ceremonies were drawn from the ranks of the aristocracy (see "Government"). In general, religious training was related to acquiring not spirits, as in regions to the north, but rather real items, such as dentalia or food.

Government The wealthiest man was generally the village leader. About 10 percent of the men made up an aristocracy known as peyerk, or "real men." Selected by elder sponsors for special training, including vision quests, they lived at higher elevations, spoke in a more elaborate style, and acquired treasures such as albino deerskins, large obsidian knives, and costumes heavily decorated with shells and seeds. They also wore finer clothing than most Yuroks, imported special food, ate with a different etiquette, hosted ceremonial gatherings, and occasionally spoke foreign languages. The peyerk occasionally gathered as a council to arbitrate disputes. "Real women" went through a similar training experience. Since children were considered a financial drain, "real women" and their husbands practiced family limitation by sexual abstinence.

Customs Social status was a function of individual wealth, which was itself a major Yurok preoccupation. Only individuals owned land, although other resources might be owned as well by villages and descent groups. Poor people could voluntarily submit to the status of slave in order to acquire some measure of wealth. Imported dentalia shells were a major measure of wealth; they were engraved, decorated, and graded into standard measures for use as money. Other forms of wealth included large obsidian blades (also imported), pileated woodpecker scalps, and albino deerskins.

Via prayer and elicitation of wrongdoing, women doctors cured by gaining control of "pains," small inanimate, disease-causing objects within people. The misuse of curing power (sorcery) could cause individual death or group famine. Intertribal social and ceremonial relations with neighbors were frequent and friendly. Yurok villages often competed against each other in games. Unlike most offenses, certain sex crimes may have been considered crimes against the community.

The basic unit of society was small groups of patrilineally related males. Marriage was accompanied by lengthy haggling over the bride price. Most couples lived with the husband’s family. Illegitimacy and adultery, being crimes against property, were considered serious. Corpses were removed from the home through the roof and buried in a family plot. If a married person died, the spouse guarded the grave until the soul’s departure for the afterworld several days after death.

Dwellings Yuroks lived in over 50 semipermanent villages; late summer and early fall were devoted to gathering expeditions. Village dwellings were small rectangular redwood-plank houses with slanted or three-pitched roofs and a central excavated pit. Platforms lined the interior. A small anteroom was located immediately inside the entrance. They housed individual biological families. Houses of people of standing were named. People lived in temporary brush shelters while away on the gathering trips.

Rectangular plank sweat houses served as dormitories for the men and boys of a kinship unit. A "rich man," or head of a paternal kin group, built this structure for himself and his male relatives. The walls lined the sides of a deep pit, within which there was a fire for providing direct heat. Men often sweated in the afternoon, alternating sweats with immersion in chilly river water, scrubbing with herbs, and reciting prayers for good fortune. Space inside the sweat house was apportioned according to rank.

Diet Acorns and salmon were riverine staples; other fish and shellfish were also eaten along the coast. Yuroks also ate sea lions, elk, deer, small game, and various roots and seeds.

Key Technology Baskets were used for a number of purposes. Many items, including houses and canoes, were fashioned of wood. Salmon were taken with weirs, poles, and nets as well as with harpoons. Yuroks may have had systems of higher mathematics.

Trade Yuroks traded canoes to the Karuk and other neighboring peoples.

Notable Arts Baskets were particularly well made, as were wood products such as sweat house stools and headrests; dugout canoes with seats, footrests, and yokes; and hollowed treasure chests.

Yurok village dwellings, like the ones pictured in this 1890 photograph, were small rectangular redwood-plank houses with slanted or three-pitched roofs and a central excavated pit.

Transportation Yuroks traveled both river and ocean on square-ended, dugout redwood canoes.

Dress Ceremonial regalia included headdresses with up to 70 redheaded-woodpecker scalps. Every adult had an arm tattoo for checking the length of dentalia strings. Everyday dress included unsoled, single-piece moccasins, leather robes (in winter), and deerskin aprons (women). Men wore few or no clothes in summer. They generally plucked their facial hair except while mourning.

War and Weapons The Yurok were not a hostile people by nature, but they feuded constantly. An elaborate wergild system, intimately connected to social status, was used to redress grievances. In their occasional fighting among themselves or with neighboring tribes—for offenses ranging from trespass and insult to murder—they avoided pitched battles, preferring to attack individuals or raid villages. Their fighting seldom resulted in many casualties. Young women were sometimes taken captive but were usually returned at the time of settlement. All fighting ended with compensation for everyone’s losses.

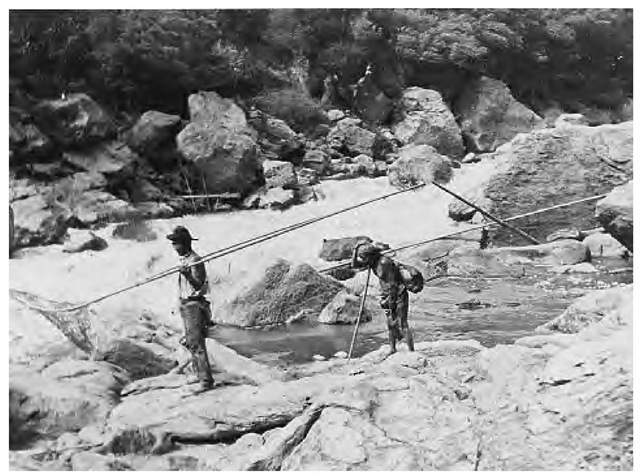

Yurok men fish on the Klamath River (1908). Among the Yurok, acorns and salmon were riverine staples; other fish and shellfish were also eaten along the coast.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations Yuroks may be found on the Hoopa Extension (Yurok) Reservation (1891; roughly 7,800 acres), the Berry Creek Rancheria (Butte County; 1916; 33 acres [Maidu]), the Resighini Reservation (Del Norte County; 1938; 228 acres [Coast Indian Community]), the Trinidad Rancheria (Humboldt County; 1917; 47 acres [Cher-Ae-Heights community]), the Big Lagoon Rancheria (Humboldt County; 1918; 20 acres; 19 Yurok and Tolowa in 1996), the Blue Lake Rancheria (Humboldt County), and the Elk Valley Rancheria (Del Norte County; 1906; 100 acres, with Tolowa and Hoopa). The first election for a Yurok Tribal Council was scheduled for 1997.

Yurok warriors wore headdresses such as this at their annual Jump Dance. The headdress, a mosaic of woodpecker scalps and bluebird feathers attached to albino deerskin, is almost 30 inches wide.

Economy Logging and fishing (commercial and subsistence) are the most important local economic activities. People also leave the communities for work in the Bay area and elsewhere. Trinidad Rancheria owns a bingo parlor, and Big Lagoon Rancheria has invested in a major hotel. The Yuroks also manage two fish hatcheries.

Legal Status The Yurok Tribe, the Big Lagoon Rancheria (Yurok and Tolowa), and the Coast Indian Community of Yurok Indians of the Resighini Rancheria are federally recognized tribal entities, as are the Hoopa Extension Reservation, the Trinidad Rancheria, the Blue Lake Rancheria, the Berry Creek Rancheria, and the Elk Valley Rancheria. In 1983, the Yuroks and the Tolowas won a protracted battle with the United States for control of a sacred mountainous site in the Six Rivers National Forest.

Daily Life Many Yuroks live semisubsistence lives of hunting, fishing, and gathering. Some still speak the Yurok language. Since the 1970s there has been a revival of traditional arts such as basket weaving and woodworking, along with some traditional ceremonies, such as the Jump and Brush Dances. Sumeg, a re-created traditional plank hamlet, was dedicated in 1990. The few peyerk who survive are almost all elderly.

The Tsurai Health Center (Trinidad Rancheria) serves the Yurok population. The application of dioxin by the U.S. Forest Service and timber companies to retard the growth of deciduous trees poses a major health problem in the area. Important ongoing issues include increasing the land base, construction of decent and affordable housing, the institution of full electrical service, protection of Indian grave sites and declining salmon stocks, and economic development.