Acoma![]() is from the Acoma and Spanish Acoma, or Acu, meaning "the place that always was" or "People of the White Rock." "Pueblo" is from the Spanish for "village." It refers both to a certain style of Southwest Indian architecture, characterized by multistory buildings made of stone and adobe, and to the people themselves. The Rio Grande pueblos are known as eastern Pueblos; Zuni, Hopi, and sometimes Acoma and Laguna are known as western Pueblos.

is from the Acoma and Spanish Acoma, or Acu, meaning "the place that always was" or "People of the White Rock." "Pueblo" is from the Spanish for "village." It refers both to a certain style of Southwest Indian architecture, characterized by multistory buildings made of stone and adobe, and to the people themselves. The Rio Grande pueblos are known as eastern Pueblos; Zuni, Hopi, and sometimes Acoma and Laguna are known as western Pueblos.

Location: Acoma is located roughly 60 miles west of Albuquerque, New Mexico. The reservation consists of three main communities: Sky City (Old Acoma), Acomita, and McCartys. The traditional lands of Acoma Pueblo encompassed roughly five million acres. Of this, roughly 10 percent is included in the reservation.

Population: The pueblo’s population was perhaps 5,000 in 1550. In 1990, 2,548 Indians lived at Acoma Pueblo; the tribal enrollment was roughly 4,000.

Language: Acoma is a Western Keresan dialect.

Historical Information

History All Pueblo people are thought to be descended from Anasazi and perhaps Mogollon and several other ancient peoples. From them they learned architecture, farming, pottery, and basketry. Larger population groups became possible with effective agriculture and the development of ways to store food surpluses. Within the context of a relatively stable existence, the people devoted increasing amounts of time and attention to religion, arts, and crafts.

In the 1200s, the Anasazi abandoned their traditional canyon homelands in response to climatic and social upheavals. A century or two of migrations ensued, followed in general by the slow reemergence of their culture in the historic pueblos. Acoma Pueblo was established at least 800 years ago.

Acoma Pueblo was first visited by non-Indians in 1539, probably by Estevan, an advance scout of the Coronado expedition. The following year the people welcomed Hernando de Alvarado, also a member of Coronado’s group. In 1598, Juan de Onate arrived in the area with settlers, founding the colony of New Mexico. However, that year Acomas killed some of his representatives, for which they faced a Spanish reprisal in 1599: The Spanish killed 800 people, tortured and enslaved others, and destroyed the pueblo. The survivors rebuilt shortly thereafter and began a process of consolidating several farming sites near Acoma, which were later recognized by the Spanish as two villages.

Onate carried on the process, already underway, of subjugating the local Indians; forcing them to pay taxes in crops, cotton, and work; and opening the door for Catholic missionaries to attack the Indians’ religion. The Spanish renamed the pueblos with saints’ names and began a program of church construction. At the same time, they introduced such new crops as peaches, wheat, and peppers into the region. In 1620, a royal decree created civil offices at each pueblo; silver-headed canes, many of which remain in use today, symbolized the governor’s authority. In 1629, the Franciscan Juan Ramirez founded a mission at Acoma and built a huge church there.

The Pueblo Indians organized and instituted a general revolt against the Spanish in 1680. For years, the Spaniards had routinely tortured Indians for practicing traditional religion. They also forced the Indians to labor for them, sold Indians into slavery, and let their cattle overgraze Indian land, a situation that eventually led to drought, erosion, and famine. Pope of San Juan Pueblo and other Pueblo religious leaders planned the revolt, sending runners carrying cords of maguey fibers to mark the day of rebellion. On August 10, 1680, a virtually united stand on the part of the Pueblos drove the Spanish from the region. The Indians killed many Spaniards but refrained from mass slaughter, allowing them to leave Santa Fe for El Paso.

The Pueblos experienced many changes during the following decades: Refugees established communities at Hopi, guerrilla fighting continued against the Spanish, and certain areas were abandoned. By the 1700s, excluding Hopi and Zuni, only Taos, Picuris, Isleta, and Acoma Pueblos had not changed locations since the arrival of the Spanish. Although Pueblo unity did not last, and Santa Fe was officially reconquered in 1692, Spanish rule was notably less severe from then on. Harsh forced labor all but ceased, and the Indians reached an understanding with the Church that enabled them to continue practicing their traditional religion. Acoma resisted further Spanish contact for several years thereafter, then bowed to Spanish power and accepted a mission.

In general, the Pueblo eighteenth century was marked by smallpox epidemics and increased raiding by the Apache, Comanche, and Ute. Occasionally Pueblo Indians fought with the Spanish against the nomadic tribes. The people practiced their religion, more or less in secret. During this time, intermarriage and regular exchange between Hispanic villages and Pueblo Indians created a new New Mexican culture, neither strictly Spanish nor Indian, but rather somewhat of a blend between the two.

Mexican "rule" in 1821 brought little immediate change to the Pueblos. The Mexicans stepped up what had been a gradual process of appropriating Indian land and water, and they allowed the nomadic tribes even greater latitude to raid. As the presence of the United States in the area grew, it attempted to enable the Pueblo Indians to continue their generally peaceful and self-sufficient ways and recognized Spanish land grants to the Pueblos. Land disputes with neighboring Laguna Pueblo were not settled so easily, however.

During the nineteenth century, the process of acculturation among Pueblo Indians quickened markedly. In an attempt to retain their identity, Pueblo Indians clung even more tenaciously to their heritage, which by now included elements of the once-hated Spanish culture and religion. By the 1880s, railroads had largely put an end to the traditional geographical isolation of the pueblos. Paradoxically, the U.S. decision to recognize Spanish land grants to the Pueblos denied Pueblo Indians certain rights granted under official treaties and left them particularly open to exploitation by squatters and thieves.

After a gap of more than 300 years, the All Indian Pueblo Council began to meet again in the 1920s, specifically in response to a congressional threat to appropriate Pueblo lands. Partly as a result of the Council’s activities, Congress confirmed Pueblo title to their lands in 1924 by passing the Pueblo Lands Act. The United States also acknowledged its trust responsibilities in a series of legal decisions and other acts of Congress. Still, especially after 1900, Pueblo culture was increasingly threatened by highly intolerant Protestant evangelical missions and schools. The Bureau of Indian Affairs also weighed in on the subject of acculturation, forcing Indian children to leave their homes and attend culture-killing boarding schools. In 1922, most Acoma children had been sent away to such schools.

Following World War II, the issue of water rights took center stage at most pueblos. Also, the All Indian Pueblo Council succeeded in slowing the threat against Pueblo lands as well as religious persecution. Making crafts for the tourist trade became an important economic activity during this period. Since the late nineteenth century, but especially after the 1960s, Pueblos have had to cope with onslaughts by (mostly white) anthropologists and seekers of Indian spirituality. The region is also known for its major art colonies at Taos and Santa Fe.

Religion In traditional Pueblo culture, religion and life are inseparable. To be in harmony with all of nature is the Pueblo ideal and way of life. The sun is seen as the representative of the Creator. Sacred mountains in each direction, plus the sun above and the earth below, define and balance the Pueblo world. Many Pueblo religious ceremonies revolve around the weather and are devoted to ensuring adequate rainfall. To this end, Pueblo Indians evoke the power of katsinas, sacred beings who live in mountains and other holy places, in ritual and dance. Each pueblo contains one or more kivas, religious chambers that symbolize the place of original emergence into this world.

In addition to the natural boundaries, Pueblo Indians created a society that defined their world by providing balanced, reciprocal relationships within which people connect and harmonize with each other, the natural world, and time itself. According to tradition, the head of each pueblo is the religious leader, or cacique, whose primary responsibility it is to watch the sun and thereby determine the dates of ceremonies. Especially in the eastern pueblos, most ceremonies are kept secret.

Government Pueblo governments derived from two traditions. Elements that are probably indigenous include the cacique, or head of the Pueblo, and the war captain, both chosen for life. These officials were intimately related to the religious structures of the pueblo and reflected the essentially theocratic nature of Pueblo government. A parallel but in most cases distinctly less powerful group of officials was imposed by the Spanish authorities. They generally dealt with external matters and included a governor, two lieutenant governors, and a council. In addition, the All Indian Pueblo Council, dating from 1598, began meeting again in the twentieth century.

Customs One mechanism that works to keep Pueblo societies coherent is a pervasive aversion to individualistic behavior. Children were traditionally raised with gentle guidance and a minimum of discipline. Pueblo Indians were generally monogamous, and divorce is relatively rare. The dead were prepared ceremonially and quickly buried. A vigil of four days and nights was generally observed.

Acoma Pueblo recognized roughly 20 matrilineal clans. The economy was basically a socialistic one, whereby labor was shared and produce was distributed equally. In modern times photography by outsiders is discouraged. At Acoma, a formal, traditional education system under the direction of the kiva headmen includes courses on human behavior, human spirit, human body, ethics, astrology, child psychology, oratory, history, music, and dance.

Dwellings Acoma Pueblo featured three rows of three-story, apartment-style dwellings, facing south on top of a 350-foot-high mesa. The lower levels were reserved mainly for storage. The buildings were constructed of adobe (earth and straw) bricks, with beams across the roof that were covered with poles, brush, and plaster. The roof of one level served as the floor of another. The levels were interconnected by ladders. As an aid to defense, the traditional design included no doors or windows; entry was through the roof. Baking ovens stood outside the buildings. Water was primarily obtained from two natural cisterns. Acoma also features seven rectangular pit houses, or kivas, for ceremonial chambers and clubhouses. The village plaza is the spiritual center of the village, where all the balanced forces of the world come together.

Diet Before the Spanish arrived, people living at Acoma Pueblo ate primarily corn, beans, and squash. Mut-tze-nee was a favorite thin corn bread. They also grew sunflowers and tobacco and kept turkeys. They hunted deer, antelope, and rabbits and gathered a variety of wild seeds, nuts, berries, and other foods. Favorite foods as of circa 1700 included a blue corn drink, corn mush, pudding, wheat cake, corn balls, paper bread, peach-bark drink, flour bread, wild berries, and prickly pear fruit. The Acomas also raised herds of sheep, goats, horses, and donkeys after the Spanish introduced these animals into the region.

Key Technology Irrigation techniques included dams and terraces. Pottery was an important technological adaptation, as was weaving baskets and cotton and tanning leather. Farming implements were made of stone and wood. Corn was ground using manos and metates.

Trade All Pueblos were part of extensive Native American trading networks that reached for a thousand miles in every direction. With the arrival of other cultures, Pueblo Indians also traded with the Hispanic American villages and then U.S. traders. At fixed times during summer or fall, enemies declared truces so that trading fairs might be held. The largest and best known was at Taos with the Comanche. Nomads exchanged slaves, buffalo hides, buckskins, jerked meat, and horses for agricultural and manufactured pueblo products. Pueblo Indians traded for shell and copper ornaments, turquoise, and macaw feathers. Trade along the Santa Fe Trail began in 1821. By the 1880s and the arrival of railroads, the Pueblos were dependent on many American-made goods, and the Native American manufacture of weaving and pottery declined and nearly died out.

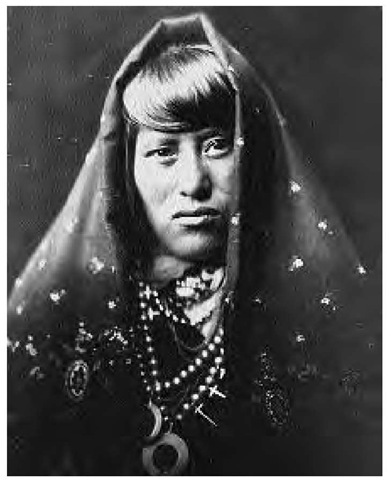

Notable Arts In the Pueblo way, art and life are inseparable. Acoma women produced excellent pottery; men made fine weavings as well as silver necklaces. Songs, dances, and dramas also qualify as traditional arts. Many Pueblos experienced a renaissance of traditional arts in the twentieth century, beginning in 1919 with San Ildefonso pottery.

Transportation Spanish horses, mules, and cattle arrived at Acoma Pueblo in the seventeenth century.

Dress Men wore cotton kilts and leather sandals. Women wore cotton dresses and sandals or high moccasin boots. Deer and rabbit skin were also used for clothing and robes.

War and Weapons Though often depicted as passive and docile, most Pueblo groups regularly engaged in warfare. Weapons included clubs, darts, spears, and stones. The great revolt of 1680 stands out as the major military action, but they also skirmished at other times with the Spanish and defended themselves against attackers such as Apaches, Comanches, and Utes. They also contributed auxiliary soldiers to provincial forces under Spain and Mexico, which were used mainly against raiding Indians and to protect merchant caravans on the Santa Fe Trail. After the raiding tribes began to pose less of a threat in the late nineteenth century, Pueblo military societies began to wither away, with the office of war captain changing to civil and religious functions.

An Acoma Pueblo woman (1910). Acoma women produced excellent pottery, while men made fine weavings as well as silver necklaces. Women wore cotton dresses and sandals or high moccasin boots.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations Acoma Pueblo, located on the aboriginal site in central New Mexico, has been continuously occupied for at least 800 years. The pueblo consists of roughly 500,000 acres of mesas, valleys, arroyos, and hills, with an average altitude of about 7,000 feet and roughly 10 inches of rain per year. Several major land purchases have added considerably to the land base since 1977. Only tribal members may own property; almost all enrolled members live on the pueblo. Acoma has been a member of the All Indian Pueblo Council since 1680. The cacique (a theological appointment, from the Antelope clan) appoints tribal council members, the governor, and his staff.

Economy Acomas grow alfalfa, oats, wheat, corn, chilies, melon, squash, vegetables, and some fruits. They also raise cattle. Acoma has coal, geothermal, and natural gas resources. Nearby uranium mines served as major employers until the 1980s. Since then, the tribe has provided most jobs. Tribal income is generated through fees charged tourists to enter Sky City (Old Acoma) as well as the associated visitor’s center, and the tribe has plans to develop the tourist trade further. Arts and crafts (pottery, silverwork, leatherwork, and beadwork) also generate some individual income.

Legal Status The Pueblo of Acoma is a federally recognized tribal entity.

Daily Life Although the project of retaining a strong Indian identity is a difficult one in the late twentieth century, Pueblo people have strong roots, and in many ways the ancient rhythms and patterns continue. Many Pueblo Indians, though nominally Catholic, have fused pieces of Catholicism onto a core of traditional beliefs. Since the 1970s control of schools has been a key in maintaining their culture. Health problems, including alcoholism and drug use, continue to plague the Pueblos. Indian Health Service hospitals often cooperate with native healers.

At Acoma, many of the old ceremonies are still performed; the religion and language are largely intact, and there is a palpable and intentional continuity with the past. Nineteen clans remain, each organized by social function. Almost all people speak Acoma and English; many older people speak Spanish as well. Many people live in traditional adobe houses, with outside ovens, but increasingly one finds cement-block ranch and frame houses with exterior stucco. Most people live below the mesa, in the villages of Acomita or McCartys.

Acoma remains a relatively closed society, like other Keresan pueblos, especially as regards religious matters. Acoma shares a junior/senior high school and a full-service hospital with neighboring Laguna Pueblo. Since the uranium mines closed, Acoma has suffered high unemployment rates. The mines have also left a legacy of radiation pollution, resulting in some health problems and the draining of the tribal fishing lake.