Northern Paiute includes a number of seminomadic, culturally distinct, and politically autonomous Great Basin groups. "Northern Paiute" is a modern construction; aboriginally, these groups were tied together only by the awareness of a common language. Paiute may have meant "True Ute" or "Water Ute" and was applied only to the Southern Paiute until the 1850s. Their self-designation was Numa, or "People." Non-natives have sometimes called these people Digger Indians, Snakes (Northern Paiutes in Oregon), and Paviotso. The Bannock Indians were originally a Northern Paiute group from eastern Oregon.

Location. Traditionally, the groups now known as Northern Paiute ranged throughout present-day southeast Oregon, extreme northeast California, extreme southwest Idaho, and northwest Nevada. Bannock territory included southeastern Idaho and western Wyoming (the Snake River region). The highly diverse environment included lakes, mountains, high plains, rivers, freshwater marsh, and high desert. Elements of California culture entered the region through groups living on or near the Sierra Nevada. Presently, Northern Paiutes live on a number of their own reservations (see "Government/ Reservations" under "Contemporary Information"), on other nearby reservations, and among the area’s general population.

Population The Paiute population in the early nineteenth century was roughly 7,500, excluding about 2,000 Bannocks. In 1990, about 6,300 Paiutes, including Paiute-Shoshones, lived on reservations.

In 1887, the Northern Paiute Wovoka, known to whites as Jack Wilson, originated the Ghost Dance religion. It was based on the belief that the world would be reborn with all Indians, alive and dead, living in a precontact paradise. Wovoka is seen seated in this 1923 publicity photo taken during the filming of the silent-era epic The Covered Wagon.

Language With Mono, Northern Paiute is part of the Western Numic (Shoshonean) branch of the Uto-Aztecan linguistic family.

Historical Information

History People later called the Bannocks, or Snakes, acquired horses as early as the mid-eighteenth century. They soon joined the Northern Shoshone in southern Idaho in developing fully mounted bands and other aspects of Plains culture, including buffalo hunting, extensive warfare, and raiding for horses.

Early Northern Paiute contacts with fur traders such as Jedediah Smith (1827) and Peter Skene Ogden (1829) were friendly, although a party led by Joseph Walker (1833) massacred about 100 peaceful Indians. When reached by whites, the Indians already had a number of non-native items in their possession, such as Spanish blankets, horses, buffalo robes, and Euro-American goods.

Most Northern Paiutes remained on foot until the late 1840s and 1850s. Around this time, heavy traffic on the Oregon and California Trails (late 1840s) and the gold rush of 1848 brought many non-natives through their territory. These people cut down pinon trees for fuel and housing, and their animals destroyed seed-bearing plants and fouled water supplies. Mining resulted in extensive and rapid resource degradation. New diseases took a heavy toll during this period. Indians responded by moving away from the invaders or attacking wagons for food and materials. White traders encouraged thefts by trading supplies for stolen items and animals. Some Indians began to live at the fringes of and work at white ranches and settlements.

Gold and silver strikes in the late 1850s fueled the cycle of conflict and violence. Local conflicts during this period included the brief Pyramid Lake war in 1860; the Owens Valley conflicts in 1862-1863; and the Coeur d’Alene war (1858-1859), which grew out of the Yakima war over white treaty violations. In the Snake war (1866-1867), Chiefs Paulina and Weawea led the Indians to early successes, but eventually the former was killed and the latter surrendered. Survivors settled on the Malheur Reservation (Oregon) in 1871. Winnemucca, who represented several hundred Northern Paiute in the 1860s and 1870s, participated in the Pyramid Lake war and, with his daughter Sarah, went on to serve as a negotiator and peacemaker. In 1873, he refused to take his band to the Malheur Reservation, holding out for a reservation of their own. The Bannocks, too, rebelled in a short-lived war over forced confinement on the Fort Hall Reservation and white treaty violations.

Beginning in 1859, the United States set aside land for Northern Paiute reservations. Eventually, a number of small reservations and colonies were created, ultimately to lose much of their land to non-Indian settlers. Most Northern Paiutes, however, drifted between reservations, combining traditional subsistence activities with growing dependence on local Anglo economies. Conflict on several reservations remained ongoing for decades (some issues are still pending) over issues such as water rights (Pyramid Lake, Walker River), white land usurpation, and fisheries destruction (Pyramid Lake). Refugees from the Bannock war were forced to move to the Yakima Reservation; from there many ultimately moved to the Warm Springs Reservation.

The government also established day and boarding schools from the late 1870s into the 1930s, including Sarah Winnemucca’s school at Lovelock. Sarah Winnemucca, who published Life Among the Paiutes in 1884, also worked tirelessly, although ultimately unsuccessfully, for a permanent Paiute reservation. Northern Paiute children also attended Indian boarding schools across the United States. Most traditional subsistence activities ceased during that period, although people continue to gather certain foods. New economic activities included cattle ranching at Fort McDermitt, stock raising, haying, and various businesses.

In 1889, the Northern Paiute Wovoka, known to the whites as Jack Wilson, started a new Ghost Dance religion. It was based on the belief that the world would be reborn with all Indians, alive and dead, living in a precontact paradise. For this to happen, Indians must reject all non-native ways, especially alcohol; live together in peace; and pray and dance. This Ghost Dance followed a previous one established at Walker River in 1869.

Family organization remained more or less intact during the reservation period. By about 1900, Northern Paiutes had lost more than 95 percent of their aboriginal territory. Most groups accepted the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) and adopted tribal councils during the 1930s. Shamanism has gradually declined over the years. The Native American Church has had adherents among the Northern Paiute since the 1930s, and the Sweat Lodge Movement became active during the 1960s.

Religion Power resided in any animate or inanimate object, feature, or phenomenon. Any person could seek power for help with a skill, but only shamans acquired enough to help, or hurt, others. A power source would expect certain specific behaviors to be followed. Most power sources also had mythological roles.

Shamans, male and female, were religious leaders. Their power often came in a recurring dream. They cured by sucking, retrieving a wandering soul, or administering medicines. Disease could be caused by soul loss, mishandling power, or sorcery. Some shamans could also control weather. Special objects as well as songs, mandated by the power dream, helped them perform their tasks. Power could also be inherited or sought by visiting certain caves.

The sun was considered an especially powerful spirit, and many people prayed to it daily. Some groups celebrated rituals associated with communal food drives or other food-related events.

Government Nuclear families, led (usually) by senior members, were the main political and economic unit. Where various families came together, the local camp was led by a headman who advised, gave speeches on right behavior, and facilitated consensus decisions. The position of headman was often, although not strictly, inherited in the male line. Camp composition changed regularly. Other elders were selected to take charge of various activities such as hunts and irrigation projects.

The traditional headman system was replaced at least in part by the emergence of chiefs during the mounted, raiding years of the 1860s and 1870s. Headmen returned during the early reservation years, however, followed by elected tribal councils beginning in the 1930s.

Customs Extended families came together semiannually (on occasions such as the fall pinon harvest) to form communities with distinct but not exclusive subsistence areas. Groups were generally named with relation to a food that they ate, a particular geographical region, or another category. After contact, some bands were named after local chiefs (e.g., Winnemucca).

Parents suggested marriages for children in their mid to late teens. Sometimes two or more siblings married two or more siblings. An exchange of presents and cohabitation formalized a marriage, with the couple usually living with the wife’s family for the first year or so. A man could have more than one wife (additional wives might include his wife’s sisters or his brother’s widow).

New parents were subject to various food and behavior restrictions. Important ceremonies were the girls’ puberty rite and the annual mourning ceremony. The former included running to and from a hill for five to ten mornings and making piles of dry brush along the way, bathing, and ritual food restrictions. Boys performed a ceremony at time of their first large game kill. They stood on a pile of sagebrush and chewed the meat and sage, placing it on their joints to make them strong.

The dead were wrapped in skin blankets and buried with their favorite possessions. Houses and other property were burned. Mourners cut their hair, wailed, and covered their faces with ashes and pitch. The mourning period lasted a year. Suspected witches were burned.

Northern Paiutes held athletic contests and played a number of games, such as the hand game, the four-stick game, and dice games.

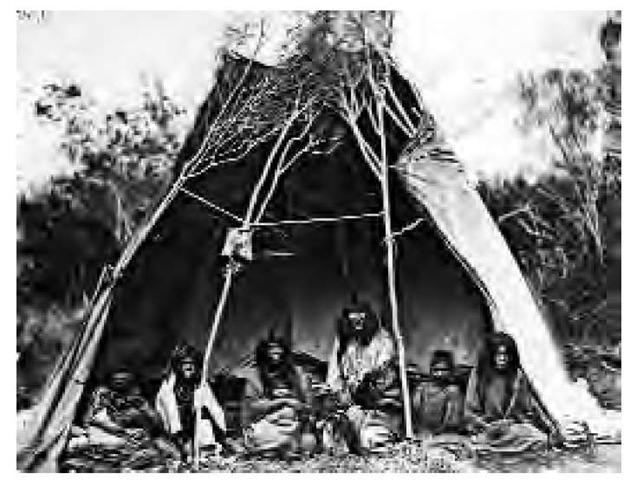

Dwellings Dwelling style and type was marked by great seasonal and regional diversity. Wickiups, used mostly in summer, were huts of brush and reeds over willow pole frames. Winter houses in the north were a cone-shaped pole framework covered with tule mats and earth. Some western groups included a mat-covered entryway. All had central fires. In the mountains, people built semisubterranean winter houses of juniper and pine boughs covered with branches and dirt. Dispersed winter camps consisted of two or three related families (roughly 50 people). In late prehistoric times, the Bannock used buffalo skin tipis during winter.

A Bannock family in camp at the head of Medicine Lodge Creek, Idaho, in 1871. Dwelling style and type was marked by great seasonal and regional diversity.

Diet Diet also varied according to specific location. Plants supplied most food needs. They included roots, bulbs, seeds, nuts, rice grass (ground into meal), cattails, berries, and greens. Roots were either eaten raw or sun dried and stored. Pine nuts and acorns were especially important. Animal foods included fowl (and eggs), squirrel, duck, and other small game as well as mountain sheep, deer, buffalo, and elk. Rabbits were hunted in communal drives. Small mammals were either pit roasted, boiled, or dried for storage. Lizards, grubs, and insects were also eaten. Trout and other fish were crucial in some areas, less important in others. Fish were usually dried and stored for winter. Some groups cultivated wild seed-bearing plants. The Bannock fished for salmon in the Snake River and hunted buffalo in the fall.

Key Technology Seed beaters, conical carrying baskets, and twined trays for gathering plant material were just some of the baskets produced by Northern Paiute women. Women shelled and ground seeds and nuts with manos and metates or wood or stone mortars and stone pestles. They used fire-hardened digging sticks to extricate roots. Fish were taken with spears, harpoons, hooks, weirs, nets, basket traps, and poison. Irrigation was carried out with dams of boulders and brush and diversion channels. Diapers and similar items were made of softened bark or cattail fluff.

Some pottery was made after about 1000. Tule and cattails were used for many purposes, such as houses, boats, matting, bags, clothing, duck decoys, and sandals. Hunting technology, which differed according to location, included the bow and arrow, traps, corral, snares, deadfalls, and stone knives. Arrow shafts were straightened, smoothed and polished with stone tools, and kept in skin quivers.

Trade Northern Paiutes obtained some Shoshone mountain sheep horn bows in trade. They also traded fish, moccasins, and beads for pine nuts, fly larvae, and shells. Their trade partners included the Maidu, other Paiute groups, and the Western Shoshone. The Bannock traded for war horses with the Nez Perce.

Notable Arts Rock art in the region is at least several thousand years old. People also made various stone, wood, and/or clay art objects. Baskets, mainly twined, were largely utilitarian.

Transportation Hunters and travelers wore snowshoes in winter. Water transportation was by tule boat. Some groups, especially the Bannock, used horses from the mid-eighteenth century on.

Dress Again, there was much regional variation based on the availability of materials. Women tended to wear tule or skin skirts, aprons, or dresses, with rabbit-skin or hide capes in winter, the edges of which were sometimes fringed and beaded. They also wore tule or hide moccasins and basket caps. Men wove the rabbit-skin blankets on a loom.

Men wore breechclouts, buckskin (or rabbit-skin or twined-sagebrush) shirts, and rabbit-skin or hide robes or capes and caps in winter. Other winter wear included rabbit-skin socks and twined-sagebrush-bark or badger-skin boots. Both sexes wore hide or sagebrush-bark leggings during winter or while hunting. They also wore headbands and feather decorations in their hair. Men plucked their facial hair and eyebrows. Shell necklaces and face and body paint were usually reserved for dances.

War and Weapons Bannock enemies included the Blackfeet and sometimes the Crow and the Nez Perce. They fought with wood and horn bows and stone-tipped arrows, spears, buffalo hide shields, and clubs.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations The following are reservations, colonies, and rancherias that have significant Northern Paiute populations:

Duck Valley Reservation, Owyhee County, Idaho, and Elko County, Nevada (1877; Shoshone and Paiute): 289,819 total acres (in Nevada and Idaho); 1,021 Indians (1990); organized under the IRA; constitution and by-laws adopted, 1936; tribal council.

Fallon Reservation and Colony, Churchill County, Nevada (1887; Paiute and Shoshone): 5,540 acres; 356 resident Indians (1990); 900 enrolled members (1992); seven-member tribal council.

Fort McDermitt Reservation, Malheur County, Oregon, and Humboldt County, Nevada (1892; Paiute and Shoshone): 35,183 acres; 387 resident Indians (1990); 689 enrolled members (1992); eight-member tribal council.

Lovelock Indian Colony, Pershing County, Nevada (1907): 20 acres; 80 resident Indians (1990); 110 enrolled members (1992); five-member tribal council.

Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, Washoe County, Nevada (1917; Washoe and Paiute): 1,984 acres; 262 resident Indians (1990); 724 enrolled members (1992); seven-member tribal council.

Summit Lake Reservation, Humboldt County, Nevada (1913): 10,500 acres; 6 resident Indians (1990); 112 enrolled members (1992); five-member tribal council.

Pyramid Lake Reservation, Lyon, Strorey, and Washoe Counties, Nevada (1874): 475,689 acres, including all of Pyramid Lake; 959 resident Indians (1990); 1,798 enrolled members (1992), almost all of whom live on the reservation; ten-member tribal council.

Walker River Reservation, Churchill, Lyon, and Mineral Counties, Nevada (1871): 323,406 acres; 822 residents (1993); 1,555 enrolled members (1993); seven-member tribal council.

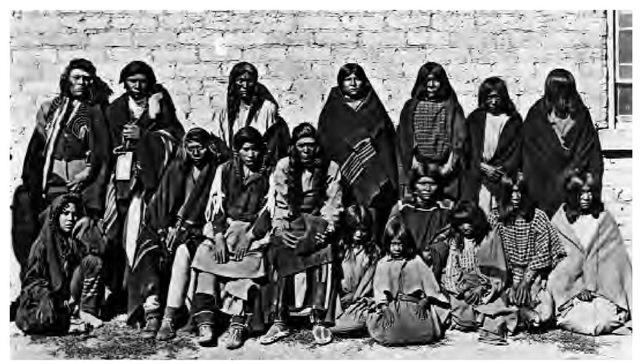

Bannock prisoners at the Snake River Reservation in Fort Hall, Idaho, September 1878.

Winnemucca Indian Colony, Humboldt County, Nevada (1971): 340 acres; 17 enrolled members (1992); five-member tribal council.

Yerington Reservation Colony and Campbell Ranch (Yerington Reservation and Trust Lands), Lyon County, Nevada (1916/1936): 1,653 total acres; 354 resident Indians (1992); 659 enrolled members (1992); organized under the IRA; constitution and by-laws adopted, 1937; seven-member tribal council.

Burns Paiute Indian Colony, Burns Paiute Reservation and Trust Lands, Harney County, Oregon (1863): 11,944 acres; 151 resident Indians (1990); 356 enrolled members (1992); five-member tribal council.

Warm Springs Reservation, Clakamas, Jefferson, Marian, and Wasco Counties, Oregon (1855; Confederated Tribes: Northern Paiute, Wallawalla [Warm Springs], and Wasco Indians): 643,507 acres; 2,818 resident Indians (1990); 123 enrolled members (1993). Decisions of the 11-member tribal council are subject to general review by referendum. The IRA constitution was adopted in 1938 (see also Wishram in Chapter 5).

Cedarville Rancheria, Modoc County, California (1914): 17 acres; six resident Indians (1990); 22 enrolled members (1992); Fort Bidwell Reservation, Modoc County, California (1897): 3,330 acres; 107 resident Indians (1990); 162 enrolled members (1992); five-member community council.

Bridgeport Indian Colony, Mono County, California (1976): 40 acres; 37 resident Indians (1990); 96 enrolled members (1992); five-member tribal council.

Susanville Rancheria, Lassen County, California (1923; Paiute, Maidu, and Pit River Indians): 140 acres; 154 Indians (1990); business council.

Benton (Utu Utu Gwaitu) Paiute Reservation, Mono County, California (1915): 160 acres; 52 resident Indians (1990); 84 enrolled members (1991); five-member tribal council.

Women are generally as active as men on tribal councils.

Economy Economic activities differ at each location. Some have no economic resources at all. Most feature some cattle ranching, agriculture on the larger reservations, and tribal businesses such as smoke shops, minimarts, and especially government (tribal) employment. Fishing and recreational activities dominate the economy at Pyramid Lake. Walker River is a member of the Council of Energy Resource Tribes (CERT). Some Indians work at off-reservation jobs. A few are able to support themselves with crafts work.

Legal Status The following Northern Paiute bands, locations, and peoples are federally recognized tribal entities: Cedarville Rancheria, Bridgeport Paiute Indian Colony, Burns Paiute Indian Colony, Fort Bidwell Indian Community, Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribes, Lovelock Paiute Tribe, Paiute-Shoshone Tribe of the Fallon Reservation and Colony, Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, Reno-Sparks Indian Colony, Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Reservation, Summit Lake Paiute Tribe, Susanville Indian Rancheria, Utu Utu Gwaitu Paiute Tribe, Walker River Paiute Tribe, Winnemucca Indian Colony, and Yerington Paiute Tribe. The Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation is a federally recognized tribal entity. The Pahrump Band of Paiutes has applied for federal recognition, as have the Washoe/Paiute of Antelope Valley, California.

Daily Life Traditional kinship relations remain relatively strong among the Northern Paiute. Although there are various language preservation programs and activities, such as the dictionary and grammar produced by the Yerington tribe, few young Northern Paiute children outside of Fort McDermitt learn to speak their native language. Health, education, and outmigration continue as significant areas of concern.

Most Northern Paiutes are Christians, although some also practice elements of their traditional religion. Others participate in regional religions such as the Native American Church, the Sweat Lodge Movement, and the Sun Dance. The Sun Dance at McDermitt Reservation, introduced in 1981, varies considerably from sun dances held among Utes and Northern and Eastern Shoshones. It includes a pipe ceremony, a peyote ceremony, and a sweat lodge ceremony. Women can dance unless they are menstruating or are pregnant. Men and women pierce themselves. This ceremony is part of the Traditional-Unity Movement.

In 1991, the Truckee River compact confirmed water rights for Pyramid Lake and Fallon; it also granted compensation for water misappropriated earlier.