Labrador or Ungava Inuit![]() , actually two groups of northeastern Inuit once differentiated by dialect and custom. Reflecting recent political developments, many people of the latter group now refer to themselves as Inuit Kapaimiut, "People of Quebec."

, actually two groups of northeastern Inuit once differentiated by dialect and custom. Reflecting recent political developments, many people of the latter group now refer to themselves as Inuit Kapaimiut, "People of Quebec."

Location From the late sixteenth century on, these people have lived on the northern half of the Labrador peninsula, especially along the coasts and the offshore islands. There is some controversy as to whether or not Inuit groups ever occupied land bordering the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Contemporary communities are either located in Labrador or Nunavik (Quebec north of the 55 th parallel).

Population The Labrador Inuit population in the mid-eighteenth century was between 3,000 and 4,200, about two-thirds of whom lived in the south. The mid-1990s Inuit population of Labrador and Nunavik was approximately 12,000 people.

Language The people speak dialects of Inuit-Inupiaq (Inuktitut), a member of the Eskaleut language family.

Historical Information

History This region has been occupied since about 2500 B.C.E., probably at first by people emigrating in waves from the Northwest. Norse explorers arrived circa 1000 C.E. The ancient Dorset culture lasted until around the fourteenth century, when it was displaced by Thule immigrants from Baffin Island. Around 1500, some Thule groups began a slow migration to the southern Labrador coast.

The people encountered Basque and other European whalers in the late fifteenth century. Inuit whaling technology was more advanced at that time. Contacts with non-native explorers, particularly those looking for the fabled northwest passage to Asia, continued throughout the sixteenth century. Early contacts between the Inuit and non-natives were generally hostile.

Whale and caribou overhunting, combined with the introduction of non-native diseases, led to population declines in the north by the late seventeenth century. The first trade centers were established in the north during the eighteenth century, although trade did not become regular there until close to the mid-nineteenth century.

In the eighteenth century, especially after the 1740s, sporadic trade began with the French fishery in the south. Moravian missions, schools, and trading posts, especially to the south, gradually became Inuit population centers after the mid- to late eighteenth century. Missionization began in Arctic Quebec in the 1860s. A mixed British-Inuit population (known as "settlers") also became established in the south from the mid-eighteenth century on. This influential group slowly grew in size and spread northward as well. Increased trade activity in the south in the mid-nineteenth century led to Inuit population declines as a result of alcohol use and disease epidemics. Fox trapping for the fur trade began in the early nineteenth century.

In the north, by later in the century, some families intermarried with non-native traders and otherwise established close relations with them. Fur trade posts became widespread in the north in the early twentieth century. Native technology began to change fundamentally and permanently during that period. Shamanism, too had all but disappeared, as most people had by then accepted Christianity, although not without much social convulsion.

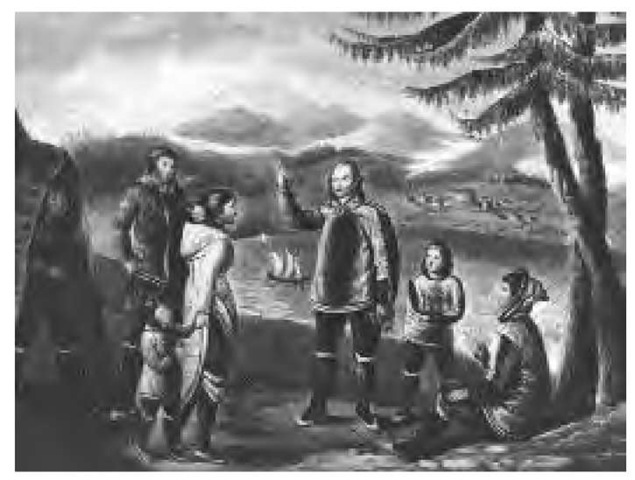

In this eighteenth-century painting, a Moravian missionary speaks to Inuit at Nain, Labrador. Moravian missions, schools, and trading posts from the mid— to late eighteenth century gradually became Inuit population centers.

In the south, the Moravians turned the Inuit trade over to the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1926. There was an increasing government presence in the 1930s and 1940s. Few or no inland groups remained in Arctic Quebec after 1930, the people having moved to the coast. About the same time, the bottom dropped out of the fox fur market. Trade posts disappeared, and many people went back to a semitraditional mode of subsistence and technology.

The far north took on strategic importance during the Cold War, about the same time that vast mineral reserves became known and technologically possible to exploit. The federal Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources (1954) encouraged the Inuit to abandon their nomadic life. Extensive Canadian government services and payments date from that time. Local Moravian missions ceded authority to the government when Labrador and Newfoundland entered the Canadian confederation in 1949.

Some of Labrador’s native communities were officially closed in the 1950s and their residents relocated. Most wage employment was of the unskilled and menial variety. By the 1960s, most people had abandoned the old ways. With radical diet changes, the adoption of a sedentary life, and the appearance of drugs and alcohol, their health declined markedly.

The entire region has experienced growing ethnopolitical awareness and activism since the 1970s. During that period, the Labrador Inuit Association (LIA) reached an accommodation with local biracial residents ("settlers") regarding representation and rights. The LIA is associated with the Inuit Tapirisat of Canada (ITC). This advocacy group works to settle land claims and to facilitate interracial cooperation. It also supports and funds local programs and services, including those relating to Inuit culture.

Religion Religious belief and practice were based on the need to appease spirit entities found in nature. Hunting, and specifically the land-sea dichotomy, was the focus of most rituals and taboos, such as that prohibiting sewing caribou-kin clothing in certain seasons. The people also recognized generative spirits, conceived of as female and identified with natural forces and cycles. Their rich cosmogony and mythology was filled with spirits and beings of various sizes, some superhuman and some subhuman.

Male and female shamans (angakok) provided religious leadership by virtue of their connection with guardian spirits. They could also control the weather, improve conditions for hunting, cure disease, and divine the future. Illness was perceived as stemming from soul loss and/or the violation of taboos and/or the anger of the dead. Curing methods included interrogation about taboo adherence, trancelike communication with spirit helpers, and performance.

Government Nuclear families were loosely organized into local groups of 20 to 30 people associated with geographical areas (-miuts). These groups occasionally came together as roughly 25 (perhaps 10 among the Ungava) small, fluid bands that were also geographically identified. The Ungava Inuit also recognized three regional bands (Siqinirmiut, Tarramiut, Itivimiut) that were identified by intermarriage and linguistic and cultural similarities.

The harpooner or boat owner provided leadership for whaling expeditions. The best hunters were often the de facto group leaders. Abuse of their authority was likely to get them killed. Still, competition for leadership positions was active, with people dueling through song and woman exchange. Women also competed with each other through singing. Local (settlement) councils helped resolve conflicts that arose in situations without a strong leader, especially in the south.

Customs Women were in charge of child rearing as well as skin and food preparation. They made the clothes, fished, hunted small animals, gathered plant material, and tended the oil lamps. Men hunted and had overall responsibility for all forms of transportation. They made and repaired utensils, weapons, and tools. They also built the houses.

Children were named for dead relatives regardless of sex; they were generally expected to take on the sex roles of their namesake, as opposed to those of their own sex. Children were occasionally brought up in the roles of the opposite gender for economic reasons. Adults occasionally married transvestites.

People married simply by announcing their intentions, although infants were regularly betrothed. Good hunters might have more than one wife (especially in the south), but most had only one. Divorce was easy to effect. Some wife exchanges were permitted within defined family partnerships; these relationships were considered as a kind of marriage.

Infanticide was rare and usually practiced against females; cannibalism, too, occasionally occurred during periods of starvation. Children were highly valued and loved, especially males. Adoption was common. The sick or aged were sometimes abandoned, especially in times of scarcity. Corpses were buried in stone graves covered by broken personal items.

Tensions were relieved through games; duels of drums and songs, in which the competing people tried to outdo each other in parody; and some "joking" relationships. Ostracism and even death were reserved for the most serious cases of socially inappropriate behavior. Murders led to ongoing blood feuds.

Dwellings The typical winter house was semiexcavated and made of stone, whalebone, and wood frames filled with sod and stone with a skin roof. Floors were also stone; windows were made of gut. Each house held up to 20 people; spaces were separated by skin partitions. The people also built mainly temporary domed snow houses. Conical and/or domed sealskin or caribou-skin tents served as summer housing. There were also large ceremonial and social structures (kashim) as well.

Diet Labrador Inuit were nomadic hunters, taking game both individually and collectively. Depending on location, they engaged in a number of subsistence activities, such as late summer and fall caribou hunting, whaling, and breathing-hole sealing in winter. They hunted seals from kayaks in spring and summer. Men and women fished year-round. People also ate birds and their eggs as well as walrus and bear (polar and black). Women gathered numerous berries and some roots as well as some shellfish and sea vegetables. Coastal hunters traveled into the interior in spring to hunt caribou, reemerging on the coast in the fall.

The results of a hunt were divided roughly equally, with those who played more important roles getting somewhat better (but not generally larger) shares. Food was eaten any number of ways, including frozen, raw, decayed, partially or fully boiled, and dried. Drinks included blood and water. There was some ritual division of "first fruits," particularly those obtained by adolescent boys or girls.

Key Technology Special harpoons, floats, and drags were used in whaling. Caribou were generally shot with bow and arrow or speared from kayaks. Birds were shot, snared, or brought down with bolas. Fish were caught with hooks, weirs, and spears.

Most tools were fashioned from caribou antlers as well as stone, bone, and driftwood. Specific tools included bone or ivory needles; thread of sinew, gut, or tendon; sealskin containers; whalebone and wooden utensils; wooden goggles with narrow eye slits; the bow drill; and soapstone (steatite) pots.

Soapstone lamps burned beluga oil (north) or caribou fat (south and interior). The latter provided light but not much heat. In the interior and more southern areas, people also molded caribou tallow candles in goose-leg skins. They started fires with pyrite, flint, and moss. Coiled baskets and woven willow mats were made around Hudson Bay.

Trade Southeastern groups imported wood for bows and arrows from the Beothuk Indians of Newfoundland. Inlanders and coastal residents exchanged dogs, ivory, caribou, and sealskins. The Inuit of present-day Quebec and those of modern Labrador engaged in regular trade. There was limited trade and contact between southern groups and the nearby Naskapi/Montagnais (Innu).

Notable Arts Art objects included woven grass baskets and carved ivory figures. There were also some petroglyphs in steatite quarries.

Transportation Travel was fairly well developed, allowing people to move with relative ease to exploit the various regions of their territory. Several types of kayaks were used generally for hunting sea mammals, birds, and caribou. Umiaks (larger, skin-covered open boats that might hold up to 30 people) were generally rowed by women on visits to offshore islands or during seasonal migrations. They were also used in the south for autumn whale hunting. Wooden sleds were pulled by dogs, who also carried some gear. Temporary boats might be made of caribou skin stuffed with branches. Long-distance walking, on snowshoes in winter, was common (snowshoes may not be native).

Dress Dress throughout Labrador was originally similar to that of the Baffinland Inuit. It consisted mainly of caribou-skin and sealskin clothing and boots. Skins of other animals were used as needed. Some island people made clothing of bird skins, especially those of ducks.

Coats probably had long flaps at the rear. Waterproof outerwear was made from gut. Other gear included sealskin boots (women of some groups wore theirs hip high) and mittens. In some areas, boots had corrugated soles made of looped leather strips.

Better hunters had newer and better clothing. Decoration was also age- and sex-appropriate. Ivory, wood, and other materials were used in clothing decoration. Some items were used as amulets or charms, whereas others were basically decorative. Women generally tattooed their faces, arms, and breasts after reaching puberty. Men occasionally tattooed noses or shoulders when they had killed a whale. Both men and women wore hair long, but women braided, rolled, and knotted theirs.

War and Weapons Inuit and Indians generally avoided each other out of mutual fear. The East Cree killed Inuit whenever possible. Intergroup and intragroup conflict regularly led to bloodshed. Hunting equipment doubled as weapons.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations Major Inuit communities in Labrador include Aqvituq (Hopedale), Nunainguk (Nain), Marruvik (Makkovik), Kikiak (Rigolet), Northwest River, Qipuqqaq (Postville), and Happy Valley/Goose Bay. Government is by locally elected community council, some dominated by "settlers."

Nunavik communities include Aupaluk, Chisasibi (also Cree), Ivujivik, Kangirsujuaq, Kangirsuk, Kangiqsualujjuaq, Kuujjuarapik, Kuujjuaq, Puvirnituq, Salluit, Tasiujaq, and Umiujaq. The Kativiq Regional Government is responsible for municipal services and various policies. There is also a local school board.

Economy Art, craft, food, and many other cooperatives date from the late 1950s. The Torngat Fish Producers Cooperative Society runs local fisheries operations. The Makivik Corporation, set up under the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) (see "Daily Life"), manages tens of millions of dollars in development funds and represents the Inuit of northern Quebec on environmental, resource, and constitutional issues. Other JBNQA corporations manage interests in air transport, construction, communications, and cultural activities. Many people depend on government employment and assistance. Subsistence, especially fishing, is most important in northern Labrador. Associated cultural behaviors and traditions, such as sharing, remain correspondingly relatively strong.

Legal Status Inuit are considered "nonstatus" native people. Most Inuit communities are incorporated as hamlets and are officially recognized. The communities listed under "Government/Reservations" are provincially and federally recognized.

Daily Life The Northern Quebec Inuit Association (1971) approved the JBNQA in 1975. It provided for local and regional administrative power as well as some special rights in the areas of land use, education, and justice. There was also monetary compensation. This controversial agreement divided the Inuit on the issue of aboriginal land rights. The opposition, centered in the locally based cooperative movement, formed the Inuit Tungavingat Nunami (ITN). This group rejects the JBNQA, including the financial compensations, carrying on its opposition activities through local levies on carvings.

A cultural revival beginning in the 1980s led to the creation of museums, cultural centers, and various studies and programs. Newspapers, air communication, television, and telephone reach even remote villages. Education is locally controlled from grades 1-12, although the curriculum differs little from those in non-native communities. Issues there include mineral and other development versus protecting renewable resources. Many local committees and associations, such as the Labrador Women’s Group (1978), provide needed social, recreational, and other services. Many Labrador Inuit still experience some ongoing racial conflict.

Traditional and modern coexist, sometimes uneasily, for many Inuit. Full-time doctors are rare in the communities. Housing is often of poor quality. Most people are Christians. Culturally, although many stabilizing patterns of traditional culture have been destroyed, many remain. Many people live as part of extended families. Adoption is widely practiced. Decisions are often taken by consensus.