Chilcotin![]() , "inhabitants of Young Man’s River." The Chilcotin were culturally related to the Carrier, the interior Salish tribes, the Bella Coola, and the Kwakiutl. They are occasionally classified among Plateau groups.

, "inhabitants of Young Man’s River." The Chilcotin were culturally related to the Carrier, the interior Salish tribes, the Bella Coola, and the Kwakiutl. They are occasionally classified among Plateau groups.

Location The territory of the Chilcotin is along the headwaters of the Chilcotin River and the Anahim Lake district and from the Coast Range to near the Fraser River, British Columbia.

Population The Chilcotin population stood at approximately 1,500 in the seventeenth century. It increased to possibly 3,500 in the late eighteenth century. There were about 500 Chilcotins in the mid-1990s.

Language Chilcotin is an Northern Athapaskan language.

Historical Information

History Chilcotins first encountered non-natives in either 1793 or 1815. Fort Alexandria, a trading post, was established in 1821. A gold strike around the Fraser River around 1860 led to the large-scale invasion of Indian lands and widespread destruction of resources, with no compensation. Indian villages and even graves were looted by the newcomers.

There was a serious smallpox epidemic in about 1862. Chilcotins sent out war parties to attack road builders. Several warriors, including Chiefs Tellot, Elexis, and Klatsassin, were captured and hanged. After the epidemics and the fighting, many survivors worked on non-native-owned ranches, since Indians were explicitly excluded from preempting land, and much of their land was confiscated.

Missionaries helped established villages that became reserves. They also significantly influenced the selection of chiefs, or headmen. Some groups merged with the Shuswap and Carrier on the Fraser River at that time. Most were located on three reserves by 1900 and were largely acculturated. "Stonies," or Stone Chilcotin bands, remained semitraditional in the western mountains. In the early twentieth century, most people hayed and/or sold a few head of cattle or some furs for a living. There was little contact with the outside world until the 1960s.

Religion Boys, and girls to some extent, went into seclusion at adolescence to acquire a guardian spirit. Spirits could be any natural phenomenon and gave the person songs and dances as well as protective power. A person who acquired many spirits might become a shaman and engage in curing and seeing what most people could not.

Shamans could use their power for evil as well as good, although evil against an individual was generally considered to be practiced only for the general good. Illnesses that were not soul related were treated by medical specialists. Souls were said to be capable of leaving the body.

Government Three or four autonomous bands were each composed of camp groups. Bands were defined as people sharing a wintering territory. There was no overall leadership, and the people never came or acted together.

Customs Bands were divided into social classes of nobles, commoners, and slaves. Nobles and commoners were arranged into clans, the most powerful of which was Raven. Descent was bilateral.

Although sharing was highly valued, some people accumulated more material goods than did others. In those cases, the surplus was generally given away—effectively exchanged for prestige—in feasts. High rank was obtained by giving potlatches. When a member of the nobility died, clans gave large potlatches, at which they gave away most of his possessions.

Early adolescence was a time for adult training. Boys focused on endurance and survival skills. Girls were isolated during their first menstrual period, at which time they observed several behavioral restrictions and performed domestic tasks. Marriage occurred shortly after this adult training. Most marriages were arranged by parents with input from the children.

Women generally did all the camp work; men were responsible for getting animal foods, fighting, and making tools. The dead were buried in the ground, cremated, or simply left under a pile of rocks or branches. People amused themselves by playing bone and dice games, snowsnake (sliding a spear along a trench in the snow for distance), ring and arrow, and athletic contests. Social control was largely internalized. Extreme violators were ostracized or, rarely, killed.

As with many Native American tribes, material goods became evenly distributed through potlatch ceremonies. Here, oxen meat is being prepared in anticipation of a potlatch in 1924.

Dwellings People generally lived in rectangular, pole-framed, earth-covered lodges with bark or brush walls and gable roofs. An open space at the top served as a smoke hole. There were also small, subterranean winter houses and dome-shaped sweat houses.

Diet Men hunted a variety of animals including caribou, elk, mountain goat, sheep, and sometimes bear. Smaller animals like marmots, beaver, and rabbits were trapped, as were fowl. Men and women caught fish such as trout, whitefish, and salmon. Women gathered camas and other roots as well a variety of berries.

Key Technology Baskets and water containers were made primarily of birch bark. Women wove rush mats and learned from the Shuswap to make coiled baskets. Fish were taken using a variety of nets and spears. Hunting equipment included the bow and arrow and stone-tipped spear. A digging stick helped women to gather camas and other roots. Food-related equipment included horn spoons, bone knives, and wooden pestles. Other tools, such as scrapers, adzes, and awls, were made mainly of bone and stone. The people also had the fire drill and made drums and flutes.

Trade Chilcotins acquired salmon from the Shuswap and Bella Coola. They also imported shell ornaments, cedar-bark headbands, wooden containers, and stone pestles from the Bella Coola. They sent dried berries, paints, and furs to the Bella Coola and furs, dentalium shells, and goat-hair blankets woven by the Bella Coola to other tribes. Snowshoes were exported in the later historical period.

Notable Arts The people made fine coiled basketry with designs of humans and animals as well as geometric shapes.

Transportation Although most travel was overland, men carved spruce-bark and dugout canoes, some with pointed prows like those of the interior Salish. Snowshoes were used for winter travel. Goods were carried in skin sacks with tumplines.

Dress Dress generally consisted of moccasins, buckskin aprons, belts, and leggings. Cold-weather gear included caps; robes of marmot, hare, or beaver; and woven wool and fur blankets. Men’s hair was generally no longer than shoulder length, although women grew their hair long and often wore it in two braids. The people used a number of personal ornaments of bone, shell, teeth, and claws. Both men and women painted or tattooed their faces and greased their bodies, face, and hair in cold, windy weather.

War and Weapons Weapons included clubs with stone heads, the bow and arrow, spears, and daggers. There was some use of hide or slat armor. Chilcotin enemies included the Carrier and Shuswap, although there was much friendly intercourse as well with these groups. Trespass was a reason to fight, as were murder and feuding. Fighters wore red and black face paint. Ritual purification, including vomiting, took place after a raid. Those who had killed lived apart from others for a time.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations The Alexandria Band owns 13 reserves with a total of 1,142 hectares of land. Band population in the mid-1990s was 135, with 59 living on reserves. The band is affiliated with the Ts’ilhqot’in Tribal Council. A chief and councilors are elected according to provisions of the Indian Act.

The Alexis Creek Tribal Government owns 37 reserves on almost 4,000 hectares of land. Band population in the mid-1990s was 496, with 345 living on reserves. A chief and councilors are elected according to provisions of the Indian Act.

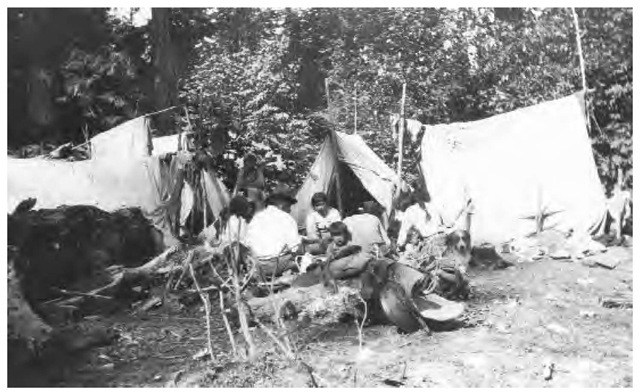

Mrs. Sam Zulin and her three children, pictured in 1924 while visiting Bella Coola, British Columbia.

The Stone Band owns five reserves on 2,146 hectares of land. Band population in the mid-1990s was 304, with 189 living on reserves. A chief and councilors are elected according to provisions of the Indian Act. The band is affiliated with the Ts’ilhqot’in National Government.

The Tl’etinqox-t’in Government (formerly the Anaham Band) owns 19 reserves on 5,656 hectares of land. Band population in the mid-1990s was 1,111, with 599 living on reserves. A chief and councilors are elected according to provisions of the Indian Act. The band is affiliated with the Ts’ilhqot’in National Government.

The Toosey Band owns four reserves on 2,582 hectares of land. Band population in the mid-1990s was 201, with 95 living on reserves. A chief and councilors are elected according to provisions of the Indian Act. The band is affiliated with the Carrier-Chilcotin Tribal Council.

Westernmost Chilcotin Indians at breakfast at a temporary camp while visiting Bella Coola, British Columbia, in 1924.

The Xeni Gwet’in First Nations Government (formerly the Neneiah Valley Band) owns eight reserves on 1,383 hectares of land. Band population in the mid-1990s was 350, with 259 living on reserves. A chief and councilors are elected according to custom. The band is affiliated with the Ts’ilhqot’in National Government.

Economy The following are important economic activities for the band members: Alexandria Band— farming and forestry; Alexis Creek and Stone Bands—farming, cattle, ranching, and forestry; Tl’etinqox-t’in Government and Xeni Gwet’in First Nations Government—farming, cattle ranching, and trapping; Toosey Band—individual farming and cattle ranching, a heavy equipment company, and trapping.

Legal Status The bands listed under "Government/ Reservations" are recognized by Canada.

Daily Life The westernmost people still cross the mountains to visit the Bella Coola. Public lands containing natural resources from which Chilcotins traditionally derived subsistence have steadily decreased since the 1960s. Children attend various band and/or provincial and/or private schools. Band facilities include an office (Alexandria Band); offices, a community hall, warehouses, and schools (Alexis Creek Band); a community center, schools, offices, and a fire station (Stone Band); offices, a community hall, schools, a carpentry building, and the Native Law Center (Tl’etinqox-t’in Government); offices, a community hall, a fire station, and a machine shed (Toosey Band); and offices, a community hall, and a rodeo field (Xeni Gwet’in).