Wrestling, at its core, is an attempt to force an opponent to submit by using holds, throws, takedowns, trips, joint locks, or chokes. Holds are attempts to immobilize an opponent by either entangling the limbs or forcing the shoulders to touch the mat, placing an opponent in a danger position. A throw is an attempt to toss a person across either the hips or shoulders, using the body as a fulcrum. A trip is an attempt by a wrestler to use legs to sweep one or both of the opponent’s legs out, forcing a fall to the ground. A takedown is an attempt to unbalance an opponent, such as by grabbing both of the legs with the arms, once again forcing a fall to the ground. A joint lock is an immobilizing lock against a limb of the opponent, such as the elbow or knee, which attempts to hyperextend the joint beyond its normal range of motion, forcing the opponent to either surrender or risk losing the limb. A choke is an attempt to cut off either the air supply or blood supply, or both, to the head, once again forcing the opponent to either surrender or suffer unconsciousness.

There are thousands of techniques in wrestling that depend on the implementation of these movements. Experienced wrestlers of any style, therefore, have a great number of techniques and combinations that they may use in combat. Strikes or percussive blows are not allowed in sport wrestling, or if they are, such techniques are purely of a secondary nature, with a throw or hold intended to be the immobilizing technique. Once blows with fists or feet become the primary weapon or balanced equally with throws and holds, then the match either becomes boxing or “all-in” fighting.

Two wrestlers at the University of Washington, ca. 1920.

Wrestling exists in many forms. There are sportive forms, in which the practitioners attempt to compete for points before judges and must play within a set of prescribed rules. Many of these sportive forms are unique to a particular culture or civilization, while other forms have gained worldwide acceptance and have been introduced into Olympic competition. Contemporary martial arts practitioners use combative forms of wrestling, and the police and military forces of many nations employ wrestling to supplement armed combat. Combative wrestling is used for self-defense purposes in environments where there are no rules. Sacred forms of wrestling are used as religious ceremonies or only practiced during religious festivals or holidays. There are even forms of wrestling that are only used for secular holidays and festivals.

There is no universal agreement as to the origin of wrestling. However, mammals of all types engage in some kind of close-in grappling when they fight. Bears hug each other in fierce grips, attempting to bite and crush their opponents. Felines, ranging from housecats to the great lions and tigers, close with each other and attempt to encircle their opponents with their fore and back legs. Primates are known to wrestle with one another both in play and in combat. The closest human relatives in the animal kingdom—gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans—have been observed to throw their fellows when playing in moves that are remarkably similar to basic wrestling throws. In addition, these creatures attempt to entangle the limbs of their opponents. It is worth speculating that many of the basic wrestling moves have been genetically imprinted in humans as instinctual methods of self-defense. Certainly the human hand, with its opposable thumb and four fingers, is ideally suited to grasping and holding.

Exactly when wrestling became a formal activity that was refined and taught, rather than an improvised activity, is unknown. It is certain, however, that wrestling has been with human society since the earliest civilizations. Wrestling in any form is a struggle between opponents that demands the ability not only to outmaneuver, but to outthink an opponent. Physical strength, although important, has always been secondary to the ability to move quickly and efficiently and to set up an opponent for a throw or hold. It has been said that wrestling matches are more like games of chess than combats, and successful wrestlers have always relied on their ability to think several moves ahead.

In this entry, wrestling will be examined in three broad contexts: historical, societal, and martial. The discussion of the historical aspect of wrestling will examine, however briefly, the development of wrestling from earliest times to the present. The treatment of the societal aspects will focus on specific types of wrestling by culture, a comparison of wrestling styles of the world, and the particular rules and limits of these styles in relation to European wrestling traditions. The discussion of the martial aspects of wrestling will examine wrestling as a martial art, as distinct from a sport. The fact that wrestling is an effective method of self-defense is often overlooked in contemporary society. Considering the myriad of techniques available to experienced wrestlers, including disarms and powerful throws, wrestling should not be characterized simply as a sport.

Western combat traditions generally are conceived of as having their origins in classical civilization. The Greeks and Romans dedicated wrestling competitions to Zeus (Roman Jupiter), the king of the gods, attesting to the importance of the activity. Our knowledge of wrestling as a formal activity, however, begins with the rise of civilization, and diverse cultural influences emerge in contemporary wrestling.

The first written records of the activity come from the Near Eastern civilizations of Babylon and Egypt, East Asia (China), and South Asia (India). Extensive descriptions of wrestling techniques in the surviving reliquaries of the Egyptian civilization date back at least to 1500 b.c. From Egypt, in fact, there comes a clear “text topic” of wrestling and fighting methods recovered from the tomb of Beni-Hassan. Various throws, holds, and takedowns are clearly illustrated through pictographs and descriptions. If, as thought by some scholars, this material was indeed conceived as a text topic of wrestling and fighting, designed to pass on instructions to future generations of students, it is one of the oldest text topics in the world. Many of the images clearly refer to techniques that are easily recognizable in modern wrestling systems: shoulder throws, hip throws, and leg sweeps.

Even earlier records dating back to the ancient Near Eastern civilizations of Sumer (ca. 3500 b.c.) and Babylon (ca. 1850 b.c.) attest to wrestling as being one of the oldest human activities. For example, the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh clearly describes wrestling techniques used by the hero and his antagonists. The early chronicles of Japan list wrestling as one of the activities practiced by the gods. In fact, every culture on the planet appears to have developed some form of wrestling, making it one of the few human activities that can be said to be universally practiced.

In East Asia, Mongolia and China both developed indigenous wrestling systems. Murals of grappling techniques paid tribute to the art in fifth-century b.c. China. Chinese shuaijiao (shuai-chiao) continues to be practiced and has been disseminated internationally. The name literally means “throwing” and “horns,” possibly a reference to the early helmets with horns that were worn by shuaijiao practitioners. Because of an apparently unbroken line of succession from this early period, shuaijiao may be the oldest continuously practiced wrestling system in the world. Shuai-jiao wrestling involves powerful throws; the competitor who is the first to land on any part of his body above the knee loses. It is surmised that shuai-jiao was originally a battlefield art. Today, shuaijiao exists as a wrestling style that is extremely popular in China, Taiwan, and Mongolia. Historically, it is likely to have influenced Western wrestling via traditional Russian systems and modern sambo.

In addition, there may be a South Asian link to Western wrestling through India. Beginning with the early civilizations of the Indus River valley (ca. 2500-1500 b.c.), there are pictographs and illustrations of figures who are clearly wrestling. In the Hindu religious text the Mahabharata, wrestling is described in detail. Even today, wrestling is practiced at village festivals in India and Pakistan. Like other forms of wrestling, competitors attempt to throw one another for points. Submission holds are neither frequent nor particularly appreciated. There are forms of all-out wrestling competition as well, known as dunghal, where practitioners fight until one submits or the contest is stopped because of injury. An argument can be made for a connection to the West via Alexander the Great’s expeditionary forces into South Asia in the third century b.c., whose members included adepts at both wrestling and pankration (all-in fighting). In the absence of written records, however, cross influences between Indian and Western wrestling traditions must remain speculative.

Not until the Greeks, however (ca. 1000 b.c.), were wrestling techniques and descriptions of champions systematically recorded in written forms in Western cultures. When the Olympic Games were initiated, wrestling was one of the original events, as was boxing. When pankration was added in 776 b.c., all three Greek unarmed combat systems were in place as Olympic events.

The goal of Greek wrestling was simple: Combatants were to force their opponents to submit without the use of striking. As a result, all holds and throws were permissible, with the exception of arm and leg locks and choke holds. Although the participants began from a standing position, it is likely that many of the events were concluded on the ground after a throw or a trip was used to force one of the competitors to the ground. When thrown, a competitor was lifted from a standing position and thrown to the ground. Examples include throwing an opponent over the shoulders or hips, with the shoulder or hip acting as a fulcrum, or facing an opponent and using the leg strength to lift and deposit the victim on the ground. Since the stadiums in which the wrestling matches were held had dirt floors, a powerful throw could momentarily stun.

Following the throw, trip, or takedown, a Greek wrestler attempted to maneuver the opponent into a submission hold. The purpose of the hold was to immobilize the opponent and place him in a danger position, such as when his shoulders touched the ground. This placed Greek wrestling at odds with pankration, in which any holds were allowed, including those that might dismember joints or choke an opponent into unconsciousness. Besides being included in the Olympics, wrestling was practiced at all athletic festivals, including those that were local, strictly intracity competitions. It was also mandatory for Greeks preparing for armed combat to study the rudiments of wrestling, boxing, or the pankration. Olympic Games, which honored the Greek deities, were ostensibly a religious form of expression. The sportive and military applications, however, were obvious. Wrestling, therefore, addressed three different spheres of life in the Greek world: religion, sport, and military training.

Despite the overall love of wrestling by Greek civilization, this martial art was not universally appreciated. Plato, in The Republic, stated that wrestlers were of dubious health and could fall seriously ill whenever they departed from their diet. In addition, several commentators expressed frustration at the many wrestling contests, including Olympic events, that were, as they believed, fixed. Still, the modern sport of wrestling in the Western world owes its roots to the practices of the ancient Greeks, beginning three thousand years ago.

When the Romans conquered the Greeks, in approximately 146 b.c., they found in the Greek world much that they admired and copied. Although they were impressed by Greek athletic preparation and by events such as wrestling, the art of wrestling as a sport never became popular in the Roman world. The Romans added no innovations to Greek wrestling; they used the techniques that had been developed over the previous centuries and adapted them to their own temporal and religious festivals. The Romans themselves much preferred the blood sports of the empire, such as fights between gladiators or animals. As a result, wrestling suffered a loss of prestige. When Christianity became the official religion of the empire in the fourth century a.d., and later when the empire fell and chaos ensued, organized sports and high-level athletic techniques such as wrestling declined as well. Although wrestling continued to be practiced, most notably for combat training, in the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) until the empire’s demise in a.d. 1453, the authority of the Eastern Orthodox Church prevented wrestling from obtaining status as a sport. The Greek love of wrestling, with its innovations and techniques, had come to an end.

Contemporaries of the Romans, however, maintained wrestling systems. The Celts were notable in this regard. Roman writings (e.g., Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic War) describe Celtic life, including armed and unarmed combat, and note that Celtic festivals included wrestling. At least two variants of these forms of wrestling still exist: Cornish wrestling, practiced in the British area of Cornwall, and Breton wrestling, practiced in the French area of Brittany. Not surprisingly, these are also two of the last remaining outposts of Celtic life on the European continent, with Cornish, a Celtic language, still being spoken into the twentieth century, and Breton, also a Celtic language, still spoken in Brittany in the twenty-first century.

Various wrestling systems, both combative and sporting, appeared in the city-states and nations that arose in Europe following the fall of the Roman Empire. For example, in the area of what is today Germany, Austria, and the Czech Republic, as early as the thirteenth century there are indications that knights and men-at-arms used wrestling techniques in hand-to-hand combat. Later, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, German fighting guilds systematically taught wrestling techniques, known as Ringen, and disarming techniques, collectively known in German as Ringen am Schwert (wrestling at the sword), as part of their curricula. The Fechtbuch (fighting topic) of Hans Talhoffer offers several pages of illustrations on what today would be classified as “getting inside the opponent,” when an unarmed grappler moves within the effective fighting range of a sword or other weapon and removes it from the armed combatant. Several other Fecht-buchs from this and later time periods clearly show methods of throwing, takedowns, and armlocks that indicate that wrestling as a combat art was in use in Europe in the Middle Ages. One exponent of wrestling, Ott the Jew, was apparently so respected in his native Austria that he was even able to transcend the boundaries of anti-Semitism that existed in European societies during this period.

The Italians, as well, developed wrestling styles and grappling systems for combat. In one of the most famous treatises of the late Middle Ages, the Italian master Pierre Monte describes wrestling as the foundation of all fighting, and goes on to state that any form of weapons training must include knowledge of how to disarm. Monte criticizes wrestling techniques of other nations, most notably the Germans, in which he believed the practice of fighting on the ground was dangerous. This evidence suggests that various schools and theories of wrestling existed in Europe during this time.

In Scandinavia as early as a.d. 700-1100, wrestling called for competitors to grasp their opponents by the waist of their pants and attempt to throw them. The person who fell to the ground first would lose. This reflected the idea that a person once thrown on a battlefield would be at the mercy of an individual with a weapon. This wrestling tradition eventually became extinct in the Scandinavian countries, but persisted in one of the last outposts to be settled by the Vikings: Iceland. Today, this wrestling variant still exists in the Icelandic sport of Glima, an Icelandic word meaning “flash.” Instead of trousers, participants wear a special belt known as a climubeltae, which simulates the wearing of trousers. A climubeltae consists of a wide belt worn around the waist with two smaller belts worn around the thighs. Competitors attempt to throw their opponents by grasping the climubeltae, and as in the ancient art from which it descends, the person who falls first or is thrown so as to touch the earth with any part of his body above the knee loses. This art form has been revived in Scandinavia and is practiced at festivals reenacting and celebrating Viking culture around the region.

Farther east, in Russia, wrestling systems developed among indigenous tribes that were later officially adopted as a part of its national culture. The ancient chronicles of the country, most notably the Lay of Igor’s Campaign, describe warriors using wrestling techniques as part of their training. This would seem to indicate that Russian warriors developed wrestling as an unarmed combat skill for use in battle. The Mongols invaded Russia in the thirteenth century, and later the Russians reversed this by moving into former Mongol-dominated regions as the Mongolian Empire began to fall apart. This move brought the Russians into contact with many different peoples, many with their own styles of wrestling. As a result, regional styles evolved. For example, traditional Siberian wrestling resembles Japanese sumo and Korean ssiritm in many respects. Other regions of Russia developed systems very similar to modern Greco-Roman and freestyle.

In the 1930s, after the overthrow of the Russian Empire and the building of the Soviet Union, the Russians developed their own form of wrestling for the entire nation: sambo. Sambo was intentionally created from the native fighting and wrestling techniques of the Russians, those of the more than 300 nationalities of the Soviet Union, and elements of Japanese judo. Sport sambo allows throws, holds, leg and arm locks, and takedowns. Combat variants also exist. Today, even after the demise of the Soviet Union, sambo enjoys international popularity.

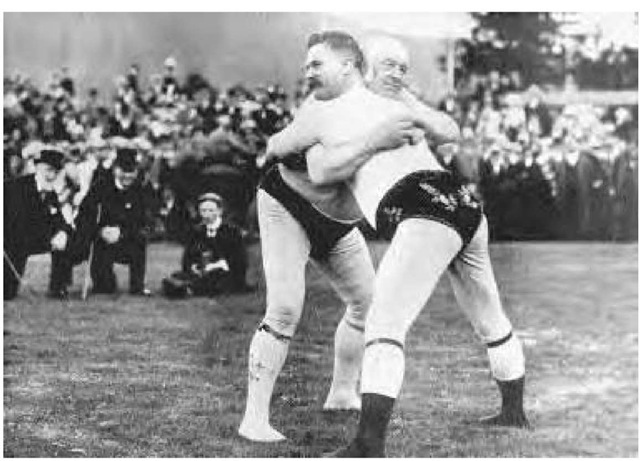

One of the giants of the Cumberland style of wrestling, George Steadman (left), and Hex Clark during a match.

The United States developed its own systems of wrestling as well. Many of the early English settlers brought with them their native systems when they settled in the “New World,” including Cornish and Cumberland/Westmorland-style wrestling from England. In the nineteenth century, catch-as-catch-can wrestling, originally from England, became popular in America. Catch-as-catch-can was a combat/sport form of wrestling in which most holds and throws/takedowns were allowed. In this respect, catch-as-catch-can was similar to Greek wrestling at the height of its popularity. Some have even compared it to pankration, although strikes were not allowed. From this catch-as-catch-can tradition, in the later nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, professional wrestling became an established sport in the country. Wrestlers such as Karl Gotch and “Farmer” Burns often challenged all comers in matches in which participants would wrestle until one surrendered. Unfortunately, however, the sport did not survive, and today the only representative from this “golden age” of American wrestling is the gaudy showmanship and theater of make-believe “professional” wrestling, currently touted as “sports entertainment.” There are attempts to revive the art, however. Today, there is a form of wrestling known as pancrase in Japan that resembles catch-as-catch-can.

Two official amateur wrestling systems exist today that may be defined as international styles because they have attempted to impose a rule structure that is uniform in application and that is intended to allow wrestlers from all nations to participate: Greco-Roman and freestyle wrestling. Both types are Olympic events. Freestyle wrestling allows competitors to grasp any part of the body and use the legs for sweeps and takedowns. Greco-Roman allows only the upper body to be used; the legs cannot be employed to sweep the opponent, nor can they be touched for grabs or takedowns. Both forms of wrestling are similar in that competitors attempt to pin their opponents by forcing the shoulders to touch the mat. Freestyle wrestling is practiced worldwide and is the most popular form of the sport. In North America, high school and college students compete in freestyle wrestling tournaments with modified rules, such as changes in the time allowed to pin an opponent. Greco-Roman is most popular in Europe. Due to the lack of worldwide acceptance of this style, however, there is talk at the present time of removing this category from Olympic competition.

Wrestling has traditionally been a male pursuit, but with the close of the twentieth century, female wrestling began to receive greater acceptance. Judo has allowed female competition for a number of decades, and in 1987, the Soviet Union allowed female sambo competitions. There is still no worldwide sanctioning body for female Greco-Roman or freestyle wrestlers. However, with the growing demand for gender equality and the passage of laws enforcing it in the United States and many European nations, it is likely that female participation in wrestling will be allowed internationally.

Wrestling is a martial art and sport that transcends national boundaries and cultural identities. Beyond the general criteria presented at the beginning of this entry, hundreds of recognized regional variants of wrestling exist in the world. A small listing includes the following: trente, from Romania and Moldavia; kokh, the national wrestling system of Armenia; Georgian jacket-wrestling, which resembles judo in many respects; dumog, one of the better-known wrestling systems from the Philippines; Schwingen, the national wrestling system of Switzerland; tegumi, a wrestling system from the island of Okinawa; lutte Parisienne, the French combat wrestling system that is often associated with the art of savate; and Corsican wrestling, from the Mediterranean island of Corsica.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, it is safe to assume that wrestling will continue to grow in popularity throughout the world. The fate of specific cultural forms of wrestling is unknown; perhaps as the world narrows into a global village these forms of wrestling will cease to be practiced. Yet, even with this possibility, the growth of wrestling as a world sport and method of combat will continue.