Japanese swordsmanship since ancient times has been a unique martial discipline of wielding a straight or curved sword using one or two hands. It evolved over more than two thousand years as an integral part of the martial culture of Japan, over time becoming an important symbol of the Japanese spirit and tradition. Swordsmanship has been practiced by court aristocracy and warriors of various affiliations as a fundamental form of fighting, together with mounted archery and halberd and spear fighting. It was first practiced to supplement other battlefield fighting methods, when close combat was inevitable. Later, it gained primacy over other forms of fighting, and eventually became transformed into a competitive sport in the modern period. The survival of swordsmanship over the centuries, and through significant transformations in the characteristics of warfare in Japan, is due to the place of the sword in Japanese culture.

The Japanese sword has always been to its bearers more than an instrument of war, marking status, social affiliation, and position or serving as a weapon with mystical powers for religious rituals. The compilers of Japanese mythology established its association with religion in the early eighth century when they recorded a battle between a fierce deity, Susa-no-o-no-mikoto, and a dragon. After slaying the dragon, the deity found an unusually long and sharp sword embedded in the dragon’s tail. He took the sword and presented it to his sister, who became the ancestral goddess of the Japanese islands and the imperial dynasty. The goddess Amaterasu (Sun Goddess) presented the sword as one of the three sacred regalia (i.e., mirror, beads, and sword) to the god who descended from the heavens to the islands. The three regalia became legitimizing symbols of the imperial dynasty’s connection to Amaterasu, marking the dynasty’s authority to rule. As such, the sword, regardless of other more practical weapons, became the symbol in the Japanese psyche of a pure heart, indomitable mind, and a sharp and decisive spirit—the ideal yamato damashii (Japanese spirit and soul).

Sword fighting in Japan began in the Jomon period (ca. tenth-third centuries b.c.), with crude stone-carved swords of approximately 50 centimeters in length that, judging from their shape, were effective for striking more than for slashing or piercing. Little is known about these prehistoric swords other than what has been unearthed in archaeological sites. Based on these findings, archaeologists have concluded that these stone-made swords were used for hunting, as symbolic instruments in religious rituals, and as instruments of warfare in actual fighting. Since they lacked the qualities of the later metal swords and those who used them were at an early stage in social development, it is highly unlikely that Jomon people developed any kind of methodological sword-fighting skills. On the other hand, having been a society of hunters and gatherers, they probably developed techniques for hunting in a group, and shared knowledge of how and where to strike various animals. Nevertheless, whatever fighting and hunting skills the Jomon people developed, it was not until later periods that techniques were developed for the use of iron swords.

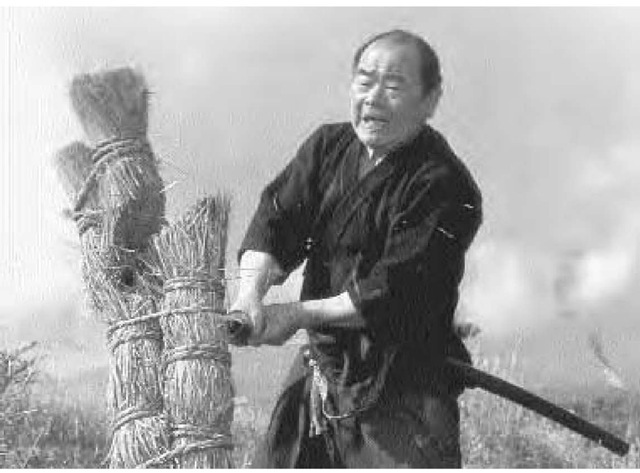

Nakamura Taizaburo in a scene from the 1979 Japanese film Eternal Budo.

Early contacts with the continent in the Yayoi period (ca. third century b.c.-third century a.d.) resulted in the introduction and importation of straight double-edged Chinese swords made of bronze. From the few remaining bronze swords most commonly found in tombs, it is clear that the quality of these swords was rather poor. Bronze swords were used to indicate the status of their holders as well as to serve in their capacity as weapons, or for religious purposes. It is interesting to note that bronze swords were shaped differently according to their function. For example, swords designed for fighting were more massive and crude, while those marking the status of its bearer were carefully crafted and designed. Furthermore, the number of battlefield bronze swords found in archaeological sites far exceeds the number of swords of the aristocracy. Based on this evidence, combined with what is known from early Chinese records of Japan, it is clear that swords and spears were used extensively in warfare associated with the consolidation of power of the Yamato king.

With improvements in metallurgy, most importantly iron casting, iron blades replaced the unsatisfactory bronze swords. The Kofun period (third-fifth centuries a.d.), when the Japanese acquired the knowledge of iron casting, marked the first significant turning point in the making and wielding of swords. By the Asuka period (fifth-sixth centuries), the Japanese were making good-quality, straight, single-edged swords that were placed in a decorated scabbard. These swords were by far more effective in cutting down an opponent than anything the Japanese had previously produced. The production and use of the sword as an effective weapon required warriors to practice wielding and stabbing. The precision with which a warrior had to wield his sword required more definite, predetermined movements, thus marking the first true swordsmanship, unsophisticated though it may have been.

The transition from sword techniques for the straight sword to those for a curved sword necessarily occurred at the same time that such curved swords were first produced. This transition occurred gradually during the tenth century, when straight swords were still used by warriors but curved swords had begun to appear. In the tenth century, Japanese makers were already experimenting with single-edged curved swords and were producing some double-edged curved swords as well. By the tenth century, with the rise of the two most important warrior families—Taira (also Heike) and Minamoto (also Genji)—and consequently, with improvements in military technology, Japanese warriors chose the single-edge curved sword. The preferred curved blade allowed for only one effective cutting edge at the outer side of the blade, while the inner side of the curvature was no longer sharpened, leaving it thick. The Japanese preference for a curved blade resulted from the nature of Japanese armor and the development of equestrian fighting skills. The hard leather or metal Japanese armor vis-a-vis the light Chinese armor, together with limitations incurred due to the seated position on a horse, gave the curved sword a better cutting power, and it was easier to draw while on horseback.

The use of swords was first recorded in the Nihon Shoki and in the Sujin-ki, where the term tachikaki to refer to sword fighting first appeared. These records provide only fragmentary information on the use of swords. More specific information on sword fighting in ancient and premodern Japan appears in the Gunki (War Tales), namely the Hogen monogatari (Tale of the Hogen), Heike monogatari (Tale of the Heike), and Taiheiki (Record of Great Peace). These and other sources indicate that from the late Heian period until the late Kamakura period, swordsmanship on the battlefield was secondary to mounted archery, which was the primary method of warfare, and to wielding halberds (naginata) and spears (hoko). Furthermore, it is clear that swords were mostly used after the warrior dismounted from his horse to engage in close combat. Mounted swordsmanship is only recorded in some picture scrolls, which rarely show warriors holding a sword while on horseback. An examination of picture scrolls further indicates that until the late Kamakura period the sword was held in the right hand only, since the design of the handle (tsuka) kept the handle short, the material hard, and the profile narrow, thus making it difficult to grip. By the Nanbokucho period (fourteenth century) the design of the sword changed to allow a better hold, making the sword more practical in battle. Descriptions of sword fights, as recorded in the Taiheiki, and examination of remaining swords from that period attest to their superior quality and to their increasing importance on the battlefield, though mounted archery seems to have maintained its primacy.

From the mid-fifteenth century, following the Onin War, Japanese swordsmanship entered an important period that lasted a century and a half. During this time, sword techniques were developed by warriors who focused their martial training on swordsmanship. The Onin War between the Yamana and Hosokawa clans on one side and Shiba and Hatakeyama clans on the other was only the beginning of almost a century of civil war, starting in Kyoto and its neighboring provinces, and later spreading countrywide. Continuous and intensive warfare, the need to keep a constant state of military readiness, and above all, the necessity of maintaining a technological advantage and a level of fighting skills higher than those of neighboring armies prompted a significant change in the approach to military training, taking it to a higher, more sophisticated, and systematic level.

Continuous civil strife brought two developments that were consequential for the formation of early schools of swordsmanship. First was the interest of the daimyo (provincial lord) in protecting his military prowess by having efficient fighting methods developed for and acquired by his army. To protect the integrity of his army, the daimyo was interested in keeping these fighting skills unique to his domain, thus being able to maintain a leverage of surprise over his enemies. Second, guarded borders and limited mobility made the intermixing of military knowledge less likely (though not impossible), as teachers of swordsmanship were now more clearly identified with and served under a single daimyo. Though distinct schools of swordsmanship, each with an identifiable skillful and charismatic founder, did not develop until the late sixteenth century, the factors mentioned above set the stage for this development in the 1500s.

Battlefield swordsmanship reached its highest level and produced a number of schools of swordsmanship during the last three decades of the sixteenth century, when civil war intensified dramatically in what is known as the Sengoku period (late sixteenth century), a period in which Japan was in a state of gekokujo (those below overthrow those above). Though expert swordsmen had been assigned to teach swordsmanship since the late Heian period, and some fourteenth-century swordsmen even formed what may be considered systematized teachings, it was only in the Sengoku and early Tokugawa (seventeenth-century) periods that these experts formed clearly defined schools, with written records, sets of techniques, and established genealogies.

A color woodblock print of a duel between Ario Maru and Karieo Maru created by Ichiyusai Kuniyoshi.

The formation of schools was possible because warriors who participated in battles and were able to achieve high skills in swordsmanship as a result of their extensive battlefield experience could rely on the name they created for themselves to attract the attention of potential patrons and followers. Indeed, patronage by prominent warriors was not hard to find because of the demand for such teachers. Ultimately, the cause for a new emphasis on sword fighting was the result of the new firearm technology, which rendered mounted archery especially inferior and vulnerable, thus making foot soldiers carrying swords replace the mounted warrior. In addition, a culture of specialized schools of art, theater performance, and craftsmanship was already in place and operating long before the formation of distinct schools of swordsmanship. Consequently, when Sengoku and early Tokugawa warriors sought to establish swordsmanship traditions, they relied on those existing schools for a model.

Two more factors contributed to the formation of specialized schools of swordsmanship. First, social mobility during the Sengoku period provided almost anybody with an opportunity to achieve recognition and advance to a higher social status. For many, swordsmanship was the way to realize their ambition. Those who mastered swordsmanship and made names for themselves on the battlefield or in challenge duels, even those of peasant origin who served as low-ranking foot soldiers, could look for rewarding positions such as being sword instructors in the service of a daimyo. Thus, self-training and perfection of techniques became essential, and they were achieved by embarking on a musha shugyo (warrior training), an increasingly popular practice since the Sengoku period. The second reason was social and political reconstruction following the erection of castle towns as domain headquarters. The large population of warriors, now removed from the countryside and relocated in these towns, was fertile ground for the sword master, who could target a large number of potential disciples without having to travel. Furthermore, sword teachers hired by the daimyo were given a residence, a place to teach, and a stipend. The benefits of becoming a teacher included prestige and a stable income, which were especially valuable later in the Tokugawa period when many samurai had lost their stipends.

The Tokugawa period (seventeenth-nineteenth centuries), during which Japan enjoyed countrywide peace and a single warrior government, had a dual effect on swordsmanship, making swordsmanship a more refined and complex martial discipline while detaching it from its battlefield context. As a result, it was transformed into a martial discipline for small-scale combat. Under new military and social conditions created by the Tokugawa shogunate, samurai were required to carry two swords, but mounted warfare or even fighting in full armor was for the most part completely abandoned. Warriors began wearing long and short swords tucked in their sashes in a tight and stable fashion as a status marker, which separated samurai from the rest of the population. Carrying swords for the purpose of engaging in battle was no longer common among Tokugawa samurai.

In addition, formation of a rigid samurai class, removal of the samurai from the countryside and placing them in urban centers or domain headquarters, and changing their function to administrators significantly reduced the need to acquire high skills in any form of fighting. Nevertheless, though many samurai became administrators, others became part of a police and inspection force. They did not abandon their martial training. Instead, they had to develop methods and techniques to solve new problems and challenges. As a result, schools of swordsmanship had to adjust existing fighting techniques and develop new ones, such as fast drawing, to accommodate much greater maneuverability on one hand and violent encounters associated with urban life on the other.

The consequences were far-reaching, as swordsmanship was no longer simply one martial discipline among others used in warfare for the sole practical purpose of survival. Tokugawa swordsmanship took on multiple forms to fit within the Tokugawa social and military context. One form of swordsmanship focused on predetermined codified sets of movements against an imaginary opponent (kata) and developed into modern iaido.

Another form subscribed to combat simulation by conducting duels using wooden or bamboo swords in sportslike duels, which included exhibition matches and formal recognition of winners, eventually evolving into modern kendo. Yet other schools chose to try and preserve swordsmanship in its early Tokugawa form, that of a real battlefield fighting skill. Though schools of swordsmanship combined all of these forms in their teachings, individual schools emphasized one form over the others, allowing for a clear separation of swordsmanship forms after the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate and the abolition of the samurai class.

Another important feature of Tokugawa swordsmanship was the association of swords and swordsmanship with divinities and related religious practices. As mentioned earlier, the establishment of a school was accompanied by compiling written records concerning its origins. These records normally included the founder’s biography and some historical information relating to the school, but often they also included legends and myths of sacred secret transmission of knowledge from legendary warriors, supernatural beings, or from the divinities themselves to the founder’s ancestors. Such divine connection provided the school with authority and “proof” of superior skills in an increasingly competitive world of swordsmanship. More importantly, the divine link to Japan’s history and mythology, in addition to the symbolic role of the sword as a mark of a samurai’s identity, instilled the notion of the sword as the mind and soul of the samurai. Practicing swordsmanship, then, took on the added importance of being a way to bring back and strengthen samurai ideals of earlier generations of warriors.

The Meiji Restoration (1868), which marked the end of warrior rule and the start of civil government in Japan, declared the Tokugawa practice of wearing two swords illegal. Centuries of warrior rule and culture came to an official end, sending traditional schools of swordsmanship into a decline, while swordsmanship itself evolved into a modern version in which the practitioners use sturdy protective gear and bamboo swords and follow prescribed rules of engagement in competition. When the Taisho (1912-1926) government added this modern swordsmanship (eventually called kendo) to the school curriculum, it immediately set it on a course to become a national martial sport. However, to preserve swordsmanship in its pre-kendo form, some schools of swordsmanship emphasized the sole practice of kata using metal swords that resemble real blades.

The practice of swordsmanship by focusing on kata is now known to many as iaido. Some kendo practitioners who reach advanced levels in kendo turn to iaido as a higher, more realistic form of swordsmanship. At any rate, the preservation of swordsmanship in kata practice follows the example of many other traditions, namely ikebana and Kabuki, among others. By attempting to perfect a predetermined set of movements, practitioners can focus on their own body movements and state of mind without being distracted by real opponents. Thus, the kata provides a vehicle for what many Japanese have always valued highly—self-improvement and character building. Even when the iaido practitioner performed the kata with a practice partner, the emphasis remained on perfection of movements and attaining a spiritual connection between the practitioners. Nevertheless, the use of wooden or metal practice swords did allow for the preservation of the combative nature of swordsmanship in kata practice, and when iaido was evaluated by the American occupation forces after World War II, it was indeed classified as a method of warfare.

Under the American occupation following the Pacific war, Japan went through a social and cultural transformation that, in the decades that followed, popularized sports competition. The American command in Japan restricted any form of martial art practice, including kendo, in official educational institutions. In response to this policy, the Japanese made a radical change to the nature of kendo by placing strong emphasis on the use of bamboo swords, which were unlike weapons of war, and re-forming kendo as a competitive sport devoid of its martial essence. Permission to practice kendo in schools in its new form was granted only in the early 1950s. For almost a decade and a half of American occupation, teachers and students who were devoted to the preservation of martial traditions and who, in many cases, were also hard-line nationalists practiced swordsmanship behind closed doors. Shortly after the Occupation ended, the Japanese government lifted the restriction on kendo, and it quickly became part of schools’ curricula once again. Similarly, kendo practice in the police force was resumed, leading to the revival of what is commonly referred to as “police kendo.” Although post-Occupation kendo includes both sports competition and traditional forms, it is much more a sport than a practical martial art. Consequently, the increasing popularity of kendo as a competitive sport, together with diminishing interest in premodern martial traditions among younger Japanese, has made old-style swordsmanship anachronistic. Moreover, the concept of swordsmanship as a fighting skill of premodern warriors has lost its meaning for the common Japanese. Therefore, the image of kendo in contemporary Japan is that of bamboo swords, body protection, rules, umpires, and tournaments. Nevertheless, it is still viewed as a practical way for building stamina and perseverance, which are viewed by Japanese as the heart of true Japanese spirit.

Currently, kendo is one of the most widely practiced forms of competitive martial sport. It remains part of school education, and is a popular choice of practice for Japanese policemen. Premodern forms of swordsmanship are gradually becoming a thing of the past, or a feature of entertainment that belongs in samurai movies. At any rate, the remaining schools of swordsmanship that teach traditional kata, or those schools where the emphasis is on actual sword fighting and less on rigid forms, have been pushed aside under the pretext of not being practical in a modern lifestyle. However, in a society where traditions die hard, it is still possible to find old forms of swordsmanship living together with the new.