Savate (from the French for “shoe”) is an indigenous martial art of France and southwestern Europe that developed from the fighting techniques of sailors, thugs, and soldiers. Although it has a reputation for being a kicking style, savate also includes hand strikes and grappling, as well as weapons. Two separate sports have derived from savate, the first a form of sport kickboxing called Boxe Frangaise, the second a form of fencing with sticks called la canne de combat. Two related arts, called chausson (French; deck shoe) and zipota (Basque; boot), also existed but today are considered part of the style of savate called “Savate Danse de Rue.”

The use of kicking techniques in Western martial arts like boxing and wrestling probably started with the Greeks and Romans in the art known as pankration. The early history is often vague, but sword manuscripts from the 1400s, such as Talhoffer Fechtbuch, also included sections on wrestling that included kicking and striking techniques along with grappling. Several of these manuals were recently collected together in a German topic on wrestling that shows what appears to be the continuation of savate-like techniques from 1447 to 1700. The earliest references to savate itself come from literature and folklore: In the 1700s a poem describes a sa-vateur (practitioner of savate) as part angel and part devil. In Basque folklore, the heroic half-bear, half-man Basso Juan uses zipota, the Basque form of savate, in his fights. In the mid-1700s, the term chausson, from the type of shoe worn on board ship, was being used to describe the fighting techniques of French, Spanish, and Portuguese sailors. As time passed, the more northern style of foot fighting was called savate while the southern style was called chausson. Chausson was more a form of play or sport, while sa-vate was more combative.

In 1803, Michel “Pisseux” Casseux opened the first salle (training hall) of savate in Paris. He had codified the techniques of savate into fifteen kicking techniques and fifteen cane techniques. About the same time, Emile Lamand began teaching savate in Madrid. Lamand adopted the local style of knife fighting (called either navaja, for a type of knife, or saca tripas [gut puller]) into his savate. As the popularity of savate increased, more sa-vatiers (old spelling) began teaching formally. Due to the poor reputation of savate at that time, the word sabotage was used in French for the act of mugging someone and a savateur was considered a brutal thug.

Some of this disapproval changed during the time of the Lecour brothers. The banning of swords within the city limits of Paris to restrict dueling caused a great increase in interest in savate by the nobility and upper class. The use of la canne (the cane) and the baton (walking stick) for self-defense and to settle disagreements became common, and many noted swordsmen took up la canne and savate. Hubert Lecour was a professional soldier and maitre d’armes (master of arms) as well as a savateur who had taught lancers in Spain the techniques of baton for defense when unhorsed. His skill and ability to popularize the art gained him many students, such as Alexander Dumas, Lord Seymour, and the duke of Orleans. The latter, a noted duelist, is credited with introducing many rapier, saber, and court sword techniques into la canne. Savate became so popular that Napoleon III mandated its use in training soldiers. During this period, the sport of canne de combat developed from the techniques of canne d’armes and fencing.

The association of savate with the French military led to savate’s exportation to many of the French colonies. In addition, French and Basque emigrants to North America carried the art with them. Depending on the length and strength of the influence, savate survived in formal salles (Ivory Coast, Algiers, French Indochina), as an informal art associated with boxing or wrestling (South Texas, Idaho, Quebec) or as a local preference for using one’s feet (Louisiana). The survival of zipota in South Texas among the Basque settlers is well documented: Zipota maitre Isdro Chapa was a retired boxing champion as well as a noted boxing coach in Laredo, Texas, who trained his fighters in zipota for use in the streets. This art had been passed down in the local boxing gyms for generations until one of his students, his nephew Paul-Raymond Buitron III, renewed the ties to the European lineage by studying in France. There is compelling evidence of its influence in South America, as well. The high arcing kicks of chausson and its practice of kicking with one hand on the floor for balance are believed to have been incorporated into Brazilian capoeira. Great similarities are seen in the techniques, salute, and dress of the old practitioners of chausson and capoeira. The presence of chausson players among the sailors in Salvador, Brazil, has been established, and French cultural influence was strong in Brazil in the 1900s. Capoeira master Bira (“Mestre Acordeon”) Almeida said in a 1996 personal communication with the author that the connection between the arts is probable and “that Chausson is one of the grandparents of Capoeira.”

Hubert Lecour’s brother, Charles, like one of his teachers, Michel Casseux, was fond of fighting and accepted challenges from fighters of any style. One should note that at this time the differences between boxing, wrestling, and savate were less defined than today, and many fighters competed in all three. Charles Lecour’s fight with the boxer Owen Swift of England ended in a draw, with Swift’s legs wrecked and Lecour’s face battered. Lecour then spent two years with Swift in England learning and adapting the punches of English boxing to savate. From this, the sport of Boxe Frangaise, the first sporting form of kickboxing, began in 1832. Charles Lecour also challenged a maitre of chausson, Joseph Vingtras, over his comments that savate lacked malice. Chausson was still practiced as a separate art at the time. The bout was well attended. Vingtras’s loss to Lecour led to the absorption of chausson’s techniques into savate.

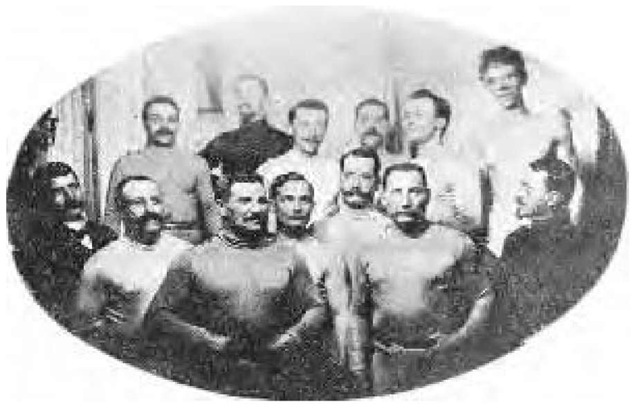

Two champions of savate (French boxing), J. Charlemont and V. Casteres (front row, third and fourth from left).

Due to the popularity of savate, the police in Paris requested and obtained a new law that sentenced anyone caught fighting with hands or feet in the street to immediate long-term enlistment in the army. The savateurs’ response led to the development of Lutte Parisienne (Parisian Wrestling), a form of grappling that hides its techniques as much as possible. Hubert Le-Broucher and Louis Vigneron were the savateurs most responsible for codifying these techniques. Vigneron techniques emphasized powerful projection throws and pinning techniques, while LeBroucher emphasized choking and neck-breaking techniques. At the same time, the savateurs in the police force began actively developing Panache (literally, plume; used to mean swagger, flourish), the use of clothing and other everyday objects to gain a quick advantage in a fight.

By the late 1870s, savate had become very popular in France. During this time Joseph Charlemont, a former legionnaire exiled to Belgium for some indiscretions, systematized the teaching of Boxe Frangaise, la Canne et Baton (cane and walking stick), and Lutte Parisienne into grades. He also developed the glove system to rank his students. Colored sashes or colored cuffs on the gloves were used. Panache was taught only to silver gloves as a final polish reserved for the highest ranks. His son, Charles Charlemont, became perhaps the greatest savateur of the time. Charles Charlemont fought and defeated the boxer Joe Driscoll in a bout called “the Fight of the Century” in 1899. This victory led to the exportation of savate to other countries, like the United States and the United Kingdom, where it was taught to the armed forces as “Automatic Defense.” Even cartoon and fictional characters such as Batman and Mrs. Peel of The Avengers television series and 1998 motion pictures have used savate in their martial arts arsenals.

The period of the two world wars was as devastating to savate as the preceding times were beneficial. By the end of World War II, it is estimated that 40 percent of France’s men had been killed in combat. Because of sa-vate’s popularity in the military and police forces, the percentage of sava-teurs killed was even greater. After World War II, one of Charlemont’s senior students, Comte Pierre Baruzy, could only find thirty-three silver gloves remaining from the over 100,000 savateurs known before World War I. This remnant led to the rebirth of savate in the modern world. However, the social conditions in Europe led to an increased emphasis on the sporting forms. Two organizations were formed after World War II, a Sa-vate and a Boxe-Frangaise Federation. Originally, judo was also one of the arts affiliated with these federations. As savate spread to other countries with similar martial traditions, an International Federation formed. In the 1970s, the two French Federations merged, and the dominance of the sport form within the association began. In the late 1970s, Lutte Parisienne was removed from the normal course of study. In 1982, a special committee for la canne and the other weapon arts was formed. While many instructors, including Comte Baruzy, opposed this and continued to teach the entire system, savate was being broken into individual disciplines with little overlap. This fragmentation continued until the 1990s when the la Canne et Baton practitioners finally developed their own organizations separate from the Savate-Boxe Frangaise Federation. During this time, savate as a complete combat art was still taught in isolated salles like that of Maitre Jean-Paul Viviane and in the police and military clubs like that of Maitre Robert Paturel. In 1994, a young American professeur (senior rank instructor), Paul-Raymond Buitron III, was charged by his maitres with developing a curriculum that requires mastery of all of the disciplines of savate as well as the formation of the International Guild of Savate Danse de Rue. Buitron was already trained in zipota when he studied savate in France, and he became the first American to earn his silver glove in France as well as the first American licensed to teach savate’s disciplines. Maitre Buitron III reintegrated the disciplines and developed a series of training sets to teach the techniques and logic of all of savate. By this effort, he preserved the full martial dimension of savate and has been called “the second Baruzy” in recognition of the amount of effort this required.

Savate Danse de Rue today trains students in the traditional disciplines of savate as one system. For technical ranks, a glove system is used: blue, green, red, white, yellow, and three grades of silver. Red is considered equal to a first-degree black belt. The basic body movements are taught from Boxe Frangaise and chausson. A pivoting of the body generates power, and kicks are focused on the toes, heel, or sole of the shoe. The trademark kicks of savate are the fouette, a spiraling kick that is vaguely similar to a roundhouse kick, and the coup de bas, a low-hitting kick. Seventeen different kicks are recognized, as well as their spinning, jumping, and main a sol (“hand on the floor”) variations. Officially, fourteen hand strikes are used, but this is a low number, as all open-hand strikes are basically considered as one type. Head, shoulder, elbow, knee, and hip strikes are also taught. After mastering bare-handed techniques, the student is introduced to the weapon system, called la canne et baton or canne d’armes. The savateur is taught in the following order: la canne (walking stick), couteau (knife), larga (cutlass or bowie), double canne, baton (heavy staff), rasoir (straight razor), firearms, and fouet (whip). The weapons are practiced against similar weapons, as in canne versus canne, against other weapons, as in canne versus couteau, and against unarmed foes. All of the weapons can be and are expected to be combined with the striking or kicking techniques as well as with grappling. The savateur’s goal is to flow between these techniques smoothly. Along with the weapon techniques, the grappling techniques of Lutte Parisienne are introduced through a series of two-person exercises. The techniques of Lutte Parisienne, derived from Western wrestling, use both projecting and breaking techniques. However, the techniques are done in such a way as to damage, not restrain, the opponents, allowing the savateur’s speedy escape. In addition, many techniques are designed to look accidental or to be hidden from witnesses. Later, the techniques of zipota are introduced to teach one how to handle multiple opponents. Zipota teaches a variety of infighting techniques and rapid changes of direction. Finally, when preparing for the first silver glove, the student studies Panache. Panache uses any available object to gain an advantage in a fight, giving it the name of “the art of malice.” For example, hats, vests, overcoats, scarves, and briefcases are used to distract or damage an assailant. The upper two grades of silver add more complicated lutte sets. In addition, familiarity with the sporting forms of Boxe Frangaise and canne de combat is required.

Despite the training of a silver glove, savateurs of that rank are not considered capable of teaching on their own. Specialized training in how to teach, the logic behind the methods of training, and the techniques are required. The colored sash recognizes teaching rank: orange for coach, purple for initiateur (one who initiates), maroon for aide moniteur (assistant monitor), and black and green for moniteur (monitor). Those who hold the honorific titles of professeur, maitre, and grande maitre wear black and red, red, and white or pure white respectively. Of the technical ranks, silver gloves wear a black and blue sash.

Students are also classed as eleves (students), disciples (disciples), and donneurs (teachers). Anyone below the silver glove is an eleve unless he has earned a teaching rank. The silver gloves and instructors below moniteur are considered disciples, or apprentices. This implies a personal relationship with a professeur who trains them in the art. Moniteurs and higher are called donneurs, as they give back to the art.