“The three manly games” of Mongolia are horse racing, archery, and wrestling. It is important to understand that all three of the heavenly games, as they are also called, are tied closely to the pastoral nomadic traditions of the Central Asian steppe. Today, these disciplines are still held in reverence, but for the most part have been codified into martial sport, with much of the military application no longer practiced or obvious.

The culmination of the sporting year in Mongolia falls during the second week of July. The festival, known as Naadam, lasts one week, during which all three sports reach their annual competitive pinnacle.

Mongolian folk wrestling as a sport dates well back into antiquity and holds a position of unrivaled cultural importance. Today Mongolian wrestling is generally held outdoors on grass, with no time limits and no weight classes. Wrestling tournaments are held during most holidays.

The objective is to get the opponent to touch any part of his back, elbow, or knee to the ground. Each match is supervised by two men who act as both referees and “corner men.” These men determine the winners and prompt the individual wrestlers to action when necessary. These individuals are arbitrarily appointed to each wrestler prior to each match. They also direct the action away from the spectators and other matches in progress. There is also a panel of judges who are solely spectators and not actively involved with the matches. They serve as the final word in disputes about takedowns and handle the logistics of the tournament.

Each wrestler has a rank, which is determined by the number of rounds successively won in each Naadam festival. (A round for an individual is made up of one match, with the winner moving to the next round and the loser being eliminated from the tournament. The winner then waits for the remainder of the matches to finish before the next round commences.) Rank can only be attained during the Naadam festival, and therefore it is not uncommon for a wrestler to wrestle his whole career without rank, though he may be successful in other tournaments throughout the year. The ranks (in order from lowest to highest) are unranked, bird, elephant, lion, and titan. The privilege of rank is that the highest-ranked wrestlers choose their opponents in each round. In addition, after each match, the lower-ranked wrestler passes under the right arm of the senior, win or lose.

Mongolian wrestling matches begin with each wrestler exhibiting a ritual dance of a great bird in flight. At the end of a match the victorious wrestler again engages in a more elaborate version of the dance. There are two popular opinions as to the type of bird being imitated. Some say the bird in question is a great falcon, while others say it is an imitation of the Garuda bird from Buddhist mythology. If the dance is done correctly, it is intended to exhibit the wrestler’s power and technique, and also serves to loosen the muscles prior to the match. In Inner Mongolia the dance is one of an eagle running before it flies. While performing the dance, the wrestler is supposed to mentally focus on Tengri (sky) and gazar (earth)—sky, or heaven, for skill and blessing and earth for stability and strength.

The attire of each wrestler is the point of most divergence between the

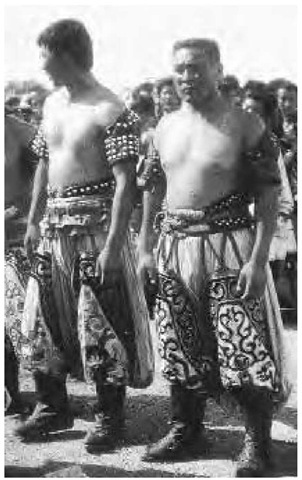

Two Inner Mongolian wrestlers await the match.

Mongolian and Inner Mongolian versions of this wrestling style. The Mongolians wear a traditional Mongolian cap (which is removed by the referees prior to each match), traditional Mongolian boots, and briefs and a short tight-fitting top, both made out of heavy cloth and silk, though today rip-stop nylon often replaces the silk. The top has long sleeves and comes midway down the back. The front of the top is cut away, exposing the chest. A rope is attached to both sides of the top and is tied around the stomach. This keeps the top on the wrestler and is used as a grip point for the opponent.

Inner Mongolians wear a heavy leather top with metal studs, which is short-sleeved and exposes much less of the chest. In addition they wear long, baggy pants and a more ornate boot. They do not use the cap at all, but do have the addition of a necklace, called a jangga, for wrestlers of rank.

Legend says that the increased exposure of the chest and the switch to briefs in Mongolia were the result of the success of a female wrestler disguised as a man several hundred years ago.

In addition to the difference in dress, Inner Mongolian wrestling has several traditions and rules different from those practiced in Mongolia. The Inner Mongolian wrestler cannot grab an opponent’s leg with his hands. In addition, any part of the body above the knee touching the ground signals a loss. Another major feature change is that in certain tournaments a circle is used as a ring boundary and a time limit is employed.

In both versions of the wrestling form, a variety of throws, trips, and lifts are employed to topple the opponent. In both versions, strangles and striking are illegal. The absence of groundwork in Mongolian wrestling is grounded (so to speak) in history. The Mongol military was entirely composed of cavalry units (except in the case of conscripts); therefore a soldier on the ground would likely be trampled by horses or killed by his opponent with a weapon. Though no longer explicitly practiced, wrestling on horseback was also a tradition that was found in Mongolia.

Two Outer Mongolian wrestlers in the middle of a tournament.

Archery is a skill for which the Mongols of antiquity were famous. The Mongol empire at its zenith owed its success to the bow and the hoof. The image of Mongol soldiers astride their mounts raining waves of arrows down upon their enemies is recorded in many histories throughout the Eurasian continent.

No account of Mongolian archery is complete without first examining the construction of the bow (num). The steppe bow, which shares some design features with the Turkish bow and is sometimes called the Chinese bow, was the primary weapon of the nomad. The steppe bow is what is today called a recurve or a reflex bow. This means that both ends of the bow curve back forward away from the archer. This feature greatly increases the power of the bow. The bow is made from composite materials of different types of wood, bone, and sinew, and is held together by a protein-based glue. The handle is made from lacquered birch bark.

According to bow makers, each material adds specific qualities to the bows: “wood for range, horn for speed, sinew for penetration, glue for union, silk bindings for firmness, lacquer for guard against frost and dew.” By the Han period, the nomads of Central Asia were employing bows of this design. The extremes in temperature found on the steppe would quickly warp other styles of bows, especially single-material bows.

The steppe bow was short, about 4 feet long, and had an extreme range of up to 500 yards in battle. The mounted archer could get off between six and twelve shots per minute. In antiquity the pulls of the bows often exceeded 100 pounds, sometimes in the range of 110-120 pounds pull. One of the advantages of a recurve bow is that after the initial pull, the bow “works with the archer” and is easier to hold at full draw.

The manner in which the bow is drawn (or in this case pushed) is also unique, in that the bow is primarily pushed away from the string rather than the string being solely pulled away from the bow. This feature has a twofold purpose. Not only is the bow stronger and often more flexible than the string, but it is an advantage, biomechanically, to push rather than pull.

The “Mongolian grip” used on the string is also unique. This grip can be identified by how the thumb hooks the string and is placed between the middle and forefinger. Traditionally, the archer wore a metal, bone, or antler ring on the thumb. Once the Chinese adopted this style of bow, the thumb ring was also sometimes made out of jade in China. The ring had a square stud on the palm side of the ring, which helped the archer in getting and maintaining his/her grip on the bowstring. In addition, the thumb ring helped the archer maintain control over the string, which, when the bow is completely drawn, is at an acute angle.

Arrowheads were constructed primarily out of bone and horn. Even today in sporting archery, bone arrowheads with squared-off tips are the standard. Modern arrows today are approximately 75 centimeters in length. Most modern bows have pulls in the 50-70 pounds pull range.

In times past, archery was practiced both afoot and mounted. Today mounted archery is rarely practiced. Though there still exist several styles of archery within Mongolia, there has been a gradual shift toward a standardized version for competitive reasons.

During archery competitions, contestants fire from afoot at targets that are traditionally made from sheep gut and are individually approximately 8 centimeters by 8 centimeters. The distance from archer to target is between 35 meters and 75 meters, depending upon the style of archery.

Archers shoot twenty arrows at two separate target constructions. One construction is a wall of stacked targets approximately 50 centimeters high and 4 meters long. The second target is a square made up of thirty individual targets. Scorers relate how the archer is faring via style-specific singing. There is some divergence in targets, bows, and ranges depending upon the style of archery in question.

Traditionally, the central feature of Mongolian society was the horse. The horse was used in every facet of steppe life. Herding, hunting, and war all took place on horseback. This lifestyle allowed the nomads to constantly perfect the major skills that gave them the military success that carried them across the world. Nomads learned to ride as soon as they could walk. Children were often placed on sheep to practice riding when they were still too small for horseback.

Horse racing in Mongolia is over natural terrain tracks that range in distance from 15 to 35 kilometers. The riders are children usually between 5 and 12 years of age. Today most races include the use of saddles, but sometimes riders, as they commonly did in the past, use modified saddles or no saddle at all.

Horse breeders pay close attention to and place equal emphasis on both mare and sire when making breeding decisions. Horses are not usually raced until about 2 years of age. As for the winners, both horse and rider are celebrated equally. Prizes are given for the first few finishers. Ceremonial songs are sung for the victorious horses. An interesting side note is that the last-place finisher also receives a ceremonial song of encouragement and promise for a strong showing next year.

Clearly, the traditional martial arts of Mongolia grew directly out of the methods of economic production dictated by life on the steppe. In essence, a Mongol was in constant preparation for war, as the horse and bow were tools of daily survival as well as war. Today we find the remnants of these methods in competitive archery and horse racing. Wrestling also is a traditional Mongolian pastime, which continues today in popularity and has widespread participation. Overall, Mongolian martial arts have become national sports as the combative uses have decreased over time. Nevertheless, today the passion among the people for their sports is still strong, and their sports elicit memories of the traditional lifestyle, which is still held in high regard.