Ki is an essential psychobiological force, which may be cultivated by and utilized in the practice of the martial arts. Throughout history, the goals of martial artists have varied between victory in combat and self-cultivation and enlightenment. One of the major theoretical assumptions of the traditional martial arts in China and Japan is an animatistic concept of impersonal power known as qi (ch’i) in Chinese or ki in Japanese. Most often described as a bioelectric life force or psychophysical energy, qi is also commonly referred to as vital breath, subtle energy, and directed intention. Qi is thought to circulate through all living things, and even though it is often a vague concept, most traditional martial arts prescribe methods of cultivating and directing this subtle energy for higher-level students. The benefits are said to include longevity, good health, power to heal injuries, and power to injure opponents and to break objects.

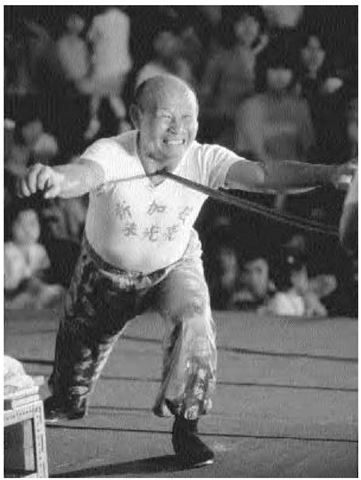

Qigong masters demonstrate the power of qi by bending swords or spears thrust into their throats.

According to traditional Sino-Japanese medical theory, qi not only permeates the universe, it also flows through the human body along paths or meridians. The flow of qi can be regulated through acupuncture, massage, or mental intent. Indeed, some researchers suggest that qi is both emotional and physiological.

Qi is particularly important in the Daoist-influenced Chinese internal martial arts, taijiquan (tai chi ch’uan), baguazhang (pa kua ch’uan), and xingyiquan (hsing i ch’uan) and in the Japanese arts most affected by aiki- jujitsu. Martial artists learn to concentrate qi in the lower dantian (a spot in the lower abdomen about three inches below the navel) and sometimes use special breathing, relaxation, and visualizations to control and direct the qi throughout their bodies.

Martial arts applications of qi theory vary but basically range from use of kiai (Japanese; spirit yell, energy unification ), in which the lower abdomen forcefully expels air with a shout such as “To,” to the development of ESP-like abilities, such as the ability to anticipate an opponent’s attack. There are many other paranormal claims made, including the ability to sense danger before it happens, control the weather, and heal with qi.

Meditation using qi energy, such as qigong (exercise or effort focused on exercising qi) meditation, appears to have physiological effects on the body and brain. Shih Tzu Kuo notes that the deep relaxation that comes with meditation reduces stress, lowers blood pressure, lowers adrenaline and lactate, and reduces oxygen consumption.

Critics of the qi concept suggest that qi is not a separate force but is simply the correct utilization of breath, mental focus, body weight, timing, and physics. By synchronization of these factors one can achieve a synergistic effect without recourse to such mystical concepts as qi.

Qi is closely associated with breath but appears in several varieties in Daoist lore. Jing Qi is a yin (the passive or negative element of the two complementary forces of yin and yang in Chinese cosmology) form of qi closely associated with sexual energy. Yuan Qi is the original energy that one inherits with one’s body and, according to some Daoists (Taoists), when Yuan Qi is finally dissipated, one dies. Shen, or heavenly qi, is associated with spiritual energy. Qi also can be seen as the bridge of energy that connects the physical body/essence to the spiritual body. Cultivation of qi is a vital part of many Asian meditative systems, and these systems have been very influential in the development of traditional martial arts.