Kalarippayattu (Malayalam; kalari, place of training; payattu, exercise) is a compound term first used in the twentieth century to identify the traditional martial art of Kerala State, southwestern coastal India. Dating from at least the twelfth century in the forms still practiced today, but with roots in both the Tamil and Dhanur Vedic martial traditions, kalarippayattu was practiced throughout the Malayalam-speaking southwestern coastal region of India (Kerala State and contiguous parts of Coorg District, Karnataka), where every village had its own kalari for the training of local fighters under the guidance of the gurukkal (honorific, respectful plural of guru) or asan (teacher). Martial masters also administer a variety of traditional Ayurvedic physical/massage therapies for muscular problems and conditions affecting the “wind humor,” and set broken bones. According to oral and written tradition, the warrior-sage Parasurama, who was the founder of Kerala, is also credited with the founding of the first kalari and subsequent lineages of teaching families. Between the twelfth century and the beginning of British rule in 1792, the practice of kalarippayattu was especially associated with subgroups of Hindu Nayars whose duty it was to serve as soldiers and physical therapists at the behest of the village head, district ruler, or local raja, having vowed to serve him to death as part of his retinue. Along with Nayars, some Cattar (or Yatra) Brahmans, one subgroup of the Ilava caste given the special title of chekor, as well as some Christians and Sufi Muslims, learned, taught, and practiced the martial art. Among at least some Nayar and Ilava families, young girls also received preliminary training until the onset of menses. We know from the local “Northern Ballads” that at least a few women students of noted Nayar and Ilava masters continued to practice and achieved a high degree of expertise. Some Ilava practitioners served the special role of fighting duels (ankam) to the death to resolve disputes and schisms among higher-caste extended families.

There was an almost constant state of low-grade warfare among local rulers from the twelfth century onward. Warfare erupted for a variety of reasons, from caste differences to pure and simple aggression. One example of interstate warfare that exemplifies the ideal bond between Nayar martial artists and their rulers is the well-documented dispute between the Zamorin of Calicut and the raja of Valluvanadu over which was to serve as convener of the great Mamakam festival held every twelve years. This “great” festival celebrated the descent of the goddess Ganga into the Bharatappuzha River in Tirunavayi, in northern Malabar. Until the thirteenth century, when the dispute probably arose, the ruler of Valluvanadu possessed the right of inaugurating and conducting the festival. The Zamorin set out to usurp this right. After a protracted conflict, the Zamorin wrested power by killing two Vellatri princes. The event created a permanent schism between the kingdoms. At each subsequent festival until its discontinuation in 1766 following the Mysorean invasion, some of the Valluvanadu fighters pledged to death in service to the royal house attended the Mamakam to avenge the honor of the fallen princes by fighting to the death against the Zamorin’s massed forces.

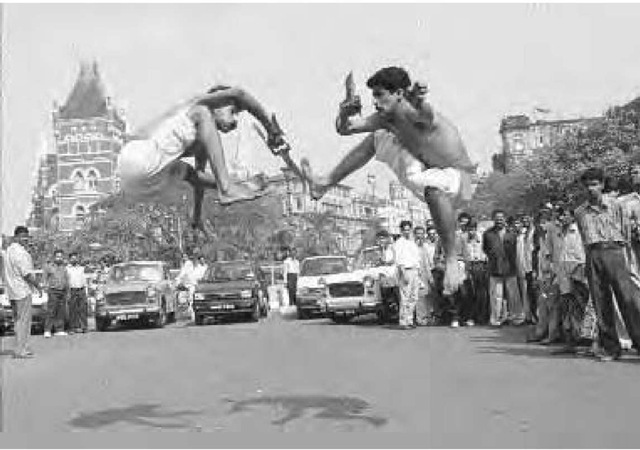

Satish Kumar (left) and Shri Ajit (right) perform a dagger fight in Bombay, December 27, 1997. The duo are in Bombay to promote Kalarippayattu, the ancient physical, cultural, and martial art of the state of Kerala in southern India.

So important was kalarippayattu in medieval Kerala that both its heroic demeanor and its practiced techniques were constantly on display, whether in actual combat, in duels, or in forms of cultural performance that included mock combats or displays of martial skills and dances and dance-dramas where the heroic was on display. Kalarippayattu directly influenced the techniques and content of numerous traditional forms of performance such as folk dances; ritual performances such as the teyyam of northern Kerala where deified heroes are worshipped; the now internationally known kathakali dance-drama, which enacts stories of India’s epic heroes based on the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and puranas; and the Christian dance-drama form, cavittu natakam, which used martial techniques for stage combat displaying the prowess of great Christian heroes like St. George and Charlemagne.

A number of today’s masters trace their lineage of practice back generations to the era when a special title (Panikkar or Kurup) was given by the local ruler. K. Sankara Narayana Menon of Chavakkad was trained by his father, Vira Sree Mudavannattil Sankunni Panikkar of Tirur, who in turn was trained by his uncle, Mudavangattil Krishna Panikkar Asan, who learned under his uncle, and so on. As recorded in the family’s palm-leaf manuscript, the Mundavannadu family was given the title An-chaimakaimal by the Vettattu raja in recognition of its exclusive responsibility for training those who fought on the Raja’s behalf and its “responsibility for destroying evil forces” in the region. Similarly, Christian master T. Tuttothu Gurukkal traces his family tradition back to Thoma Panikkar, who held the rank of commander-in-chief (commandandi) for the Christian soldiers serving the Chmpakasserry raja until his fall in 1754.

Kalarippayattu declined under British rule, due to the introduction of firearms and the organization of police, armies, and government institutions along European institutional models, but survived under the tutelage of a few masters in scattered regions of Kerala, especially in the north. During the modern era kalarippayattu was first brought to general public attention during the 1920s in a wave of rediscovery of indigenous arts. In 1958, two years after the founding of a united, Malayalam-speaking Kerala State government, the first modern association, the Kerala Kalarippayat (sic) Association, was founded under the leadership of Govindankutty Na-yar, with fifteen member kalari, as one of seventeen members of the Kerala States Sports Council. Despite increasing public awareness within the north Malabar region in particular, and in the state capital, kalarippayattu continued to be little known as a practical martial and healing art to the general public in Kerala and in India as late as the 1970s. Since then kalarip-payattu has become known throughout Kerala, India, and more recently throughout the world.

Historically there were many different styles and lineages of kalarip-payattu, including Arappukai, Pillatanni, Vatten Tirippu, and Dronamballi Sampradayam. A number of distinctive styles were suppressed or lost, especially during the nineteenth century in the south of Kerala, where a greater effort took place to suppress the authority of the Nayars and to centralize power along European institutional models. Although the Kerala Kalarippayat Association officially recognizes three styles of kalarippay-attu according to the rough geographical area where each originated, that is, northern, central, and southern styles, what is called southern-style kalarippayattu today is also known as varma ati or adi murai, and it is best discussed separately, since its myth of origin and techniques of practice, though clearly related to kalarippayattu, are different enough to warrant separate consideration. The remainder of this entry focuses primarily on northern style, with a brief description of central style.

The traditional practice of kalarippayattu is informed by key principles and assumptions about the body, consciousness, the body-mind relationship, health, and exercise drawn from Kerala’s unique versions of yoga practice and philosophy, South Asian medicine (called Ayurveda [Sanskrit; science of life]), and religious mythology, practices, and histories. The Malayalam folk expression “The body becomes all eyes” encapsulates the ideal state of the practitioner, whose response to his environment should be like Brahma the thousand-eyed—able to see and respond intuitively, like an animal, to anything. To attain this ideal state of awareness, traditional masters emphasize that one must “possess complete knowledge of the body.” This traditionally meant gaining knowledge of three different “bodies of practice”: (1) the fluid body of humors and saps, associated with Ayurveda, in which there should be a healthful congruence of the body’s humors through vigorous, seasonal exercise; (2) the body composed of bones, muscles, and the vulnerable vital junctures or spots (marmmam) of the body; and (3) the subtle, interior body, assumed in the practice of yoga, through which the internal “serpent power” (kundalini sakti) is awakened for use in martial practice and in giving healing therapies.

Training toward this ideal began traditionally at the age of 7 in specially constructed kalari, ideally dug out of the ground so that they are pits with a plaited coconut palm roof above. The kalari itself is considered a temple, and in Hindu kalari from seven to twenty-one deities are considered present, and worshipped on a daily basis, at least during the training season. After undergoing a ritual process of initiation into training and paying respects to the gurukkal, the student in the northern style of kalar-ippayattu begins by oiling the body and practicing a vigorous array of “body preparation” exercises, including poses, kicks, steps, jumps, and leg exercises performed in increasingly complex combinations back and forth across the kalari floor. Most important is mastery of basic poses, named after animals such as the elephant, horse, and lion, comparable to yoga postures (asanas), and steps that join one pose to another. Repetitious practice of these vigorous physical forms is understood to eventually render the external body flexible and “flowing like a river” as students literally “wash the floor of the kalari with their sweat.”

In addition to the techniques described above, the central style includes distinctive techniques performed within floor drawings, known as kalam, traced with rice powder on the floor of the kalari. Special steps for attack and defense are learned within a five-circle pattern so that the student moves in triangles, or zigzags. In addition, some masters of central style teach cumattadi, sequences of “steps and hits” based on particular animal poses and performed in four directions, instilling in the student the ability to respond to attacks from all directions.

Traditionally, preliminary training took place during the cool monsoon period (June-September), and also included undergoing a vigorous full-body massage given with the master’s feet as he held onto ropes suspended from the ceiling of the kalari. As with the practice of yoga, special restrictions and observances traditionally circumscribed training, such as not sleeping during the day while in training, refraining from sexual intercourse during the days when one was receiving the intensive massage, not waking at night, and taking milk and ghee (clarified butter) in the diet. From the first day of training students are admonished to participate in the devotional life of the kalari, including paying respects to and ideally internalizing worship of the guardian deity of the kalari, usually a form of a goddess (Bhagavati, Bhadrakali) or Siva and Sakti, the primary god and goddess worshiped in Kerala, in combination.

The exercise, sweating, and oil massage are understood to stimulate all forms of the wind humor to course through the body. Long-term practice enhances the ability to endure fatigue by balancing the three humors, and it enables the practitioner to acquire the characteristic internal and external ease of movement and body fluidity. The accomplished practitioner’s movements “flow,” thereby clearing up the “channels” (nadi) of the internal subtle body.

Only when a student is physically, spiritually, and ethically ready is he supposed to be allowed to take up the first weapon in the training system. If the body and mind have been fully prepared, then the weapon becomes an extension of the body-mind. The student first learns wooden weapons (kolttari)—first long staff, later short stick, and then a curved stick known as an otta—through which empty-hand combat is taught. After several years of training, combat weapons are introduced, including dagger, spear, mace (gada), sword and shield, double-edged sword (curika) versus sword, spear versus sword and shield, and flexible sword (urumi). In the distant past, bow and arrow was also practiced, but this has been lost in the kalar-ippayattu tradition. All weapons teach attack and defense of the body’s vital spots.

Empty-hand techniques are taught either through otta or through special “empty-hand” techniques (verumkai) taught as part of advanced training. For example, C. Mohammed Sherif teaches eighteen basic empty-hand attacks and twelve methods of blocking, which were traditionally part of at least some northern Kerala styles. Eventually, students also should begin to discover applications that are implicit or hidden in the regular daily body exercises. In some forms of empty-hand training, special attention is given to application of techniques to striking or penetrating the vital spots (marmam) of the body—those junctures that are so vulnerable that an attack on them can in some cases lead to instant death. The earliest textual evidence of the concept of the vital spots dates from as early as the Rig Veda (ca. 1200 b.c.), in which the god Indra is recorded as defeating the demon Vrtra by attacking his vital spot with a vajra (thunderbolt). By the time that Susruta wrote the classic Sanskrit medical text in the second century a.d., 107 vital spots had been identified as an aid to surgical intervention. Over the years the notion of the vital spots has been central to martial and healing practices, since the master must learn the location of the vital spots to attack them, to provide the emergency procedure of a “counter-application” with his hands when an individual has been injured by having a vital spot penetrated, or to avoid them when giving therapeutic massages.

Martial practice, like meditation, is understood to tame and purify the external body (sthula-sarira), as it quiets and balances the body’s three humors. Eventually the practitioner should begin to discover the internal/subtle body (suksma sarira) most often identified with Kundalini/tantric yoga. For martial practitioners this discovery is essential for embodying power (sakti) to be used in combat, or for healing through the massage therapies. Long-term training involves the development of single-point focus (eka-grata) and mental power (manasakti). A variety of meditation techniques have traditionally been practiced as part of the development of these subtler powers and abilities, so that martial artists could conquer themselves, that is, their fears, anxieties, and doubts, as well as gain access to specific and subtler forms of sakti for application.

These subtler aspects of practice include simple forms of vratam— simply sitting in an appropriately quiet place and focusing one’s mind on a deity through repetition of the deity’s name. A more advanced technique is to sit in the cat pose, facing the guardian deity of the kalari, and repeat the verbal commands for a particular body exercise sequence while maintaining long, deep, sustained breathing. Repetition of such exercises is understood to lead to dharana—a more concentrated and “higher” form of one-point concentration. Subtler and secretive practices include becoming accomplished in particular mantras. Ubiquitous to Hinduism from as early as the Vedas and to all aspects of kalarippayattu practice from ritual propitiation of the deities, to administering massage, and to weapons practice are repetition of mantras. Usually taking the form of a series of sacred words and/or syllables, which may or may not be translatable, these are considered “instruments of power . . . designed for a particular task, which will achieve a particular end when, and only when, . . . used in a particular manner” (Alper 1989, 6). Kalarippayattu masters in the past had a “tool box” of such mantras, each of which had specific purposes: (1) mantras for worship of a specific deity; (2) personal mantras to develop the character of the student; (3) mantras associated with particular animal poses to gain superior power and actualization of that pose; (4) weapons or combat mantras used for a specific technique to give it additional power; (5) all-purpose mantras to gain access to higher powers of attack or defense; and (6) medical/healing mantras used when preparing a particular medicine or giving a particular treatment. These secrets are given only to the most advanced students, and many masters are loath to teach them today. When they are taught, a student is told never to reveal the mantras since to do so would “spoil the power of the mantras.”

Although kalarippayattu has undergone a resurgence of interest during the 1980s and 1990s, its traditional practice can, when compared to more overt streetwise forms of karate and kung fu, seem anachronistic to young people wanting immediate results in order to practice a martial art that looks like what they see at the cinema.