Sperm whales include the cetacean families Physeteridae (the modern sperm whale) and Kogiidae (the modern pygmy and dwarf sperm whales). Modem sperm whales are represented by two genera only, but sperm whales were much more diverse in past times. Phylogenetically, sperm whales are usually thought to be close to the root of the odontocetes, and they retain many characters that are primitive for odontocetes. They do, however, also have some highly derived features and are not very similar to the primitive Eocene cetaceans (archaeocetes) that they are descended from. Physeterids and kogiids may be subsequent branches of the basal odontocete phylogenetic tree, or both may be derived from a common sperm whale ancestor, such as Ferecetotherium (Table I).

I. Physeteridae

Physeterids (including the modern sperm whale Physeter niacrocephalus) are highly specialized for teutophagy at great depths, and many parts of sperm whale anatomy show adaptations for this behavior. Some specialized morphologies are already present in the oldest known physeterid, Ferecetotherium kelloggi, from the late Oligocene of Azerbajan, but many fossil sperm whales were probably fisheaters.

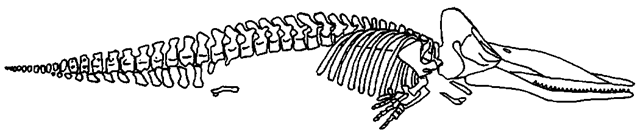

The earliest physeterid, Ferecetotherium, was small (approximately 5 m long) and had a small head. An increase in size and head size occurred in the Miocene, and modern Physeter has a body length of 16 m in females and 21 m in males. The Better Known Genera of Physeteridae and Kogiidae head of P. macrocephalus is approximately one-third the size of the body. An increase in body size happened throughout physeterid evolution (Fig. 1).

|

Physeteridae |

|

|

|

Ferecetotherium |

Late Oligocene |

Azerbajan |

|

Diaphorocetus |

Early Miocene |

Argentina |

|

Aulophyseter |

Middle Miocene |

United States, west coast |

|

Idiorophus |

Middle Miocene |

United States, west coast |

|

Orycterocetus |

Middle Miocene |

United States, east coast |

|

Placoziphius |

Upper Miocene |

Europe |

|

Scaldicetus |

Middle Miocene |

Europe, Japan |

|

Physeter |

Recent |

All oceans, except polar |

|

Kogiidae |

|

|

|

Kogiopsis |

Late Miocene |

United States |

|

Scaphokogia |

Miocene |

Peru |

|

Praekogia |

Pliocene |

Mexico |

|

Kogia |

Recent |

All temporal to |

|

|

|

tropical oceans |

Ferecetotherium had a relatively narrow rostrum. Miocene sperm whales are characterized by the widening of the rostrum. This widening took different paths in different species. In some clades, widening occurred in the maxillae and premaxillae, whereas in other clades only one of these elements enlarged. In the Miocene Diaphorocetus and Orycterocetus, the premaxilla and maxilla are nearly equal in width near the base of the rostrum, but the tip of the rostrum consists entirely of the premaxillae. In contrast, in Physeter the maxillae make up nearly all of the rostrum, and the premaxillae are only exposed near the tip of the rostrum. Widening of the rostrum was probably the result of the enlargement of the spermaceti organ, a large structure housed in a depression (the supracranial basin) on the forehead. The supracranial basin is characteristic of sperm whales, although it is relatively small in older forms. Posteriorly, this basin is bounded by the supraoc-cipital and the posterior plate of the right premaxilla, and laterally vertical plates of the frontals bound the basin. In modern Physeter, the lateral walls of the supraoccipital basin are formed by the maxillae. All physeterids, including Ferecetotherium, are also characterized by strong asymmetry of the rostrum, particularly the premaxillae and nasals.

Large evolutionary changes also occurred in the mandible. In modern sperm whales, the maxilla (upper jaw) is much wider than the mandible as a result of the widening of the rostrum and a narrowing of the mandible. These give the lower jaw a peculiar undersized image. This mismatch evolved gradually in physeterids. Ferecetotherium has a primitive mandible, not unlike that of archaeocetes. In late Eocene archaeocetes, the lower margin of the mandible is horizontal, but the mandibular depth increases posteriorly and teeth are present on the ascending ramus. Physeterid specializations in the mandible of Ferecetotherium include the parallel edges of the ramus, the superior displacement of the mandibular condyle, and the reduced coronoid process.

As a rule, modern Physeter only has teeth in the lower jaw, although occasionally an individual is found with upper teeth. Upper teeth are still present in physeterids from Oligocene through middle Miocene. Teeth in Physeter are positioned in the upper edge of the mandible. In Ferecetotherium, posterior teeth are rooted in the upper edge of the mandible, but anterior teeth (except the first tooth) are implanted more laterally. The latter condition occurs in all teeth of Kogia. All physeterids have homodont and polydont teeth, as do most extant odontocetes. The tooth crowns of physeterids are small, and their roots are more shallow than those of archaeocetes.

In physeterid evolution, the length of mandibular symphysis increased from one-twelfth of the length of the mandible in the Oligocene to one-fourth in the Miocene, and one-half in Physeter. The mandible of Ferecetotherium has 27 teeth, whereas that of Diaphorocetus has 14. In the middle Miocene Aulo-physeter morricei, upper teeth, if present at all, were only lodged in the gums, and all upper teeth were lost in the upper Miocene Placoziphius duboisii.

The great differences in the shape of the face and jaws between early physeterids and modern ones suggest that the teu-tophagic specializations of Physeter may not have been present in extinct relatives. It is possible that Oligocene and Miocene physeterids were ichthyophagous, as were most cetaceans. Modern sperm whales feed on deep-sea squid, and it is likely that early physeterids were not deep-sea animals.

The forelimb of physeterids is very different from that of Eocene cetaceans, but similar to that of other odontocetes. The humerus is shortened and the elbow is immobile. The hand forms a flat, smooth surface with no differentiation of individual fingers, causing the entire limb to be an effective nidder. In early physeterids, the head of the humerus changed considerably. The humeral head of Ferecetotherium is deviated externally and faces caudally, but the tubercles are situated anteriorly, as in archaic cetaceans. Whereas Ferecetotherium retains a greater and lesser tublercle of the humerus, the lesser tubercle of Miocene physetends is enlarged greatly and the greater tublercle reduced. Phy-seter has a weak lesser tubercle, set medially on the humerus.

Figure 1 Skeleton of Physeter macrocephalus, the modern sperm whale. Note the disproportion-ally large head and the supracranial basin.

II. Kogiidae

One genus with two modern species constitutes the Kogiidae (Kogia breviceps and K sima). Kogia is similar to Physeter, but the body of Kogia is much smaller (body length approximately 4 m) and the head is smaller (one-sixth to one-eighth of the body). The spermaceti organ is smaller than in Physeter, the blowhole more posterior, and the rostrum shorter. Proportions of the head in Physeter embryos are similar to those of adult Kogia. This suggests that these cetaceans are closely related and that Physeter has a more derived facial morphology.

Kogiids are poorly represented in the fossil record, and most specimens are incomplete. The genus Kogiopsis is known from a single mandible, and fragmentary skulls are known for Miocene Scaphokogia and Pliocene Praekogia. Another trend in the evolution of kogiids is the reduction of dental enamel. This trend started in the Miocene. In modern Kogia some enamel covers the tips of the teeth, whereas Miocene kogiids lack all enamel.

Phylogenetically, Scaphokogia is a basal branch of kogiids, retaining primitive morphologies of rostrum, premaxillae, and intermaxillary groove. It is, however, more derived than other kogiids in having a well-developed supracranial basin. Scaphokogia may represent an early, specialized branch of kogiids, the subfamily Scaphokogiidae. These went extinct near the end of the Miocene. Praekogia is closely related to Kogia in that both the nasal passages are anterior due to poorly developed telescoping.