Pinnipeds reproduce in a wide range of marine habitats, including various forms of ice, tidal flats, rock outcrop-pings, and coastal beaches (Scheffer, 1958). Some species form annual breeding aggregations at traditional locations known as rookeries. These reproductive sites are an integral component of the animals’ life history patterns, resulting from a complex suite of adaptive factors involving physiology, morphology, ecology, and distribution. Rookery-breeding pinnipeds exhibit varying forms of polygyny (Boness, 1991); this mode of social organization is believed to have evolved as a consequence of two key traits; parturition on solid substrate and offshore marine foraging (Bartholomew, 1970). The influence of these traits in conjunction with phylogenetic and ecological constraints has likely influenced the development of the polygynous mating systems observed on rookeries today (Em-Iin and Oring, 1977; Stirling, 1983; Boness, 1991; Boyd, 1991).

Rookery-breeding pinnipeds are subdivided into two families: Otariidae and Phocidae. Rookeries are formed by all otariids (15 species) and three phocids [2 species of elephant seal.

Mirounga angustirostris and M. Iconina, and gray seals, Hali-choerus grtjpus (Reeves et al, 1992; Rice, 1998)]. This article describes the salient social-biological, physical-geographical, and environmental characteristics of pinniped rookeries and provides information on the ecological context in which they occur.

I. Social-Biological Characteristics

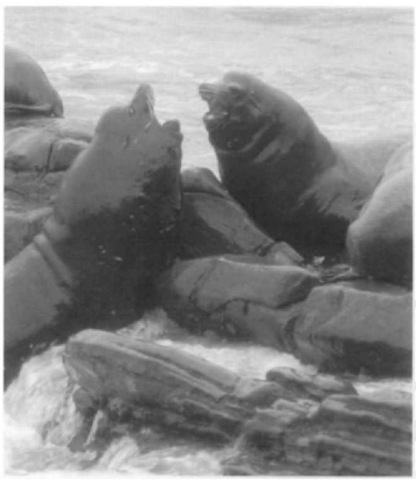

Rookeries are formed at specific times and locations, which optimize the reproductive success and survival of offspring (Bartholomew, 1970; Stirling, 1983; Boyd, 1991). After foraging at sea during die nonbreeding season, adult males return to rookeries and begin establishing territories shortly before or about die same time as die arrival of parturient females. Overt aggression, frequent direat vocalizations, and ritualized boundary displays are common among males when establishing and defending territories (Fig. 1). Males also attempt to herd females in an effort to keep diem widiin their areas of influence (Fig. 2). Adult females come ashore to find suitable parturition sites and tend to be highly gregarious. Parturient females frequently direaten one another either vocally or visually and are often aggressive toward offspring of other females. Otariid females suckle their pups for about 4-12 mondis, although longer periods have been documented for some species (Oftedal et al, 1987; Bowen, 1991). Lactation of rookery-breeding phocid females lasts about 0.5 (gray seals) to 1.0 (elephant seals) month. Estrus occurs early in lactation for otariids and late in lactation for phocids (Oftedal et al, 1987). Most copulations occur on land at or near the parturition site, but a few species commonly breed aquaticaUy in the intertidal zone where males maintain aquatic territories. Otariid females intermittendy leave the rookery to forage between suckling periods, and phocid females fast on land during die entire lactation period. Thus, some pinnipeds rookeries may be occupied continuously, but most breeding is completed within a relatively short time period of about 2 months.

Figure 1 Adult male California sea lions (Zalophus californi-anus) compete for territories at San Miguel Island, California

Figure 2 A much larger and darker adult male California sea lion attempts to block an adult female from leaving his territory at San Miguel Island, California (NMFS, George Antonelis).

Sexual dimorphism is apparent on pinniped rookeries, as adult males usually have distinctly different characteristics and are larger than females. Each sex and species emits stereotypic vocalizations for long- and short-distance communication (Stirling and Warneke, 1971; Miller, 1991). Males emit loud longdistance threat calls toward other males. Lactating otariid females also emit loud pup attraction calls on rookeries to locate their offspring among hundreds of pups. Short-distance threat vocalizations are common on all pinniped rookeries and have less amplitude than long-distance calls. Noise from rookeries initially may be perceived as a cacophony of sounds, but what seems to be chaos is really a well-organized social structure that has evolved over millions of years.

II. Physical-Geographical Characteristics

Pinniped rookeries are typically found on remote offshore islands, akhough some occur on mainland beaches. Rookeries are formed near shoreline just above the tidal zone in a variety of substraits, including sand, cobble or boulder beaches, rock shelves, and caves. Breeding aggregations usually occur within several hundred meters of the shoreline and also may occur on hillsides or cliffs overlooking the ocean (Fig. 3). Low-growing vegetation such as low grasses or shrubs is common on some rookeries.

The formation of rookeries on substrate near but above the tidal zone provides several functions that reinforce continued use of each site. To ensure survival to weaning, neonates are usually born in locations where high tides do not wash them away from their mothers or compromise their ability to thermoregu-late (Fig. 4). The gregariousness of females at these nearshore locations facilitates the ability of territorial males to monopolize estrous females, a key component of their complex polygynous mating system (Emlin and Oring, 1977). During anomalous conditions, however, storm surf associated with El Nino events has flooded pinniped rookeries, resulting in significant neonatal mortality and disruption of their polygynous social structure (Trillmich and Ono, 1991). Such events demonstrate the need for rookeries to occur above normal fluctuations in tide height.

Figure 3 California sea lions are highly polygynous and form dense aggregations on rookeries commonly found along the shoreline at breeding sites on the California Channel Islands (NMFS, George Antonelis).

Although pinniped rookeries must be.located above the tidal zone, they must also be close enough to the water to facilitate access for thermoregulation, foraging trips by lactating females, or escape from terrestrial predators. During high air temperatures in tropical and temperate environments, many rookery-breeding otariids are known to move regularly to the intertidal zone for cooling.

Figure 4 A female California sea lion suckles her pup in a location protected from the surf on San Miguel Island, California (NMFS, George Antonelis).

III. Environmental Characteristics

Environmental characteristics related to the formation, timing, and use of pinniped rookeries vary among species and are likely stimulated by proximate factors such as photoperiod, nutrition, and climate, which ultimately relate to survival and reproductive success (Boyd, 1991). The relative importance of these factors is believed to differ according to species on spatial and temporal scales. Pinniped rookeries occur most commonly during the spring and summer months when climatic conditions are relatively warm and the frequency of inclement weather diminishes. Such conditions increase the probability of offspring survival, especially in subpolar climates. Rookery-breeding phocids are the exceptions and form aggregations on rookeries in the fall and winter.

Most rookeries occur in locations where oceanographic conditions result in high productivity. High productivity increases the availability of potential prey resources vital for the foraging success of otariid females, which must feed intermittently during lactation. Rookery-breeding phocid females do not forage during lactation and rely completely on the energy stores obtained before parturition. The availability of prey near rookeries is therefore much more important to otariids than to phocids. However, the availability of prey for pups either before or after weaning may be an essential component for successful transition to foraging self-sufficiency for the young of most pinnipeds born on rookeries.