Although marine mammals are regarded as accomplished , and sophisticated hunters, they too are preyed upon by a variety of terrestrial, avian, and aquatic predators. Predation is an ecological factor of significant influence on the behavior and organization of animal societies in general, and the need for protection from predation has likely been an important factor in the evolution of most marine mammal social systems. While the risk of predation is of little or no concern for some species, other exist under high levels of predatory pressure. A large portion of all marine mammals, ranging in size from the enormous blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) to the relatively small sea otter (Enhijdra lutris), are subjected to varying levels of predation. Responses to predators are complex and include detection and avoidance, fleeing, seeking habitat features for cover, and active defense by individuals as well as coordinated groups.

While the topic of predation is expansive and multidimensional, the focus of the following article centers on the hunting and consumption of marine mammals by their predators. The definition of predation used here excludes parasitism, filter feeding, scavenging (carrion eating), or browsing and is limited to situations in which an animal expends time and energy to locate living prey and exerts additional effort to kill and consume it. Therefore, predation is distinguished from other forms of foraging in that it concludes with the death of an animal that offers some resistance against being discovered and/or being harmed.

I. Predation on Sirenians

The relatively slow moving and rather lethargic behavior of sirenians (manatees, Trichechus spp., and dugongs, Dugong dugon) makes them seem particularly vulnerable to predation. However, manatees and dugongs actually have few known natural predators and appear to experience only occasional mortality due to predation. Although large sharks, crocodiles (Croc-odijlus spp.), and killer whales (Orcinus orca) are all considered to be potential predators, few records exist to confirm these suspicions. Evidence of predation, including tooth scarring indicative of unsuccessful attacks by predators, has been observed only rarely during long-term field studies on manatees (Trichechus manatus) in Florida and dugongs off Australia. The limited presence of marine predators in the relatively warm and shallow nearshore waters, rivers, and bays where these animals forage on marine vegetation may partially explain the paucity of observed predatory interactions. Further, the particularly thick skin and exceedingly dense bone characteristic of the sirenians may render them rather unpalatable and serve to deter potential predators.

Predation on sirenians does occur, however. For example, in South America, Amazon manatees (T. inunguis) are reported to be preyed on by jaguars (Panthera onca) and large sharks, and marine crocodiles mav occasionally kill dugongs throughout their distribution. Off Western Australia, predation by killer whales on adult dugongs has been reported, including one occasion when 10 killer whales were observed attacking a group of approximately 40 dugongs in shallow water. During this incident the dugongs were huddled tightly together in an an-tipredator response, while pieces of flesh and integument floated nearby in blood-stained water. Local residents of Western Australia have also implicated “black porpoises” as predators of dugongs: however, what species these “porpoises” represent is entirelv unclear. While some authors suggest that these porpoise attacks were likely to be by killer whales, such records may also refer to one of several other mammal-killing cetaceans such as the false killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens), pygmy killer whale (Feresa attenuata), or short-finned pilot whale (Globicephala macrorhi/nchus). It is conceivable, of course, that predation on sirenians is considerably higher than has been observed and reported. Predatoiy attacks on young animals, for example, may be particularly successful, and information regarding the predator-related mortality of species such as the West African (T. senegalensis) and Amazon manatees that mainly occur in areas inaccessible to researchers is largely unknown.

II. Predation on Mustelids

Although sharks and killer whales represent the primary predators of sea otters several terrestrial and avian predators have also been documented. Coyotes (Canis latrans) are known to prey on recently weaned otters in parts of Alaska, and Russian brown bears (Ursus arctos) occasionally kill otters that haul out along the shores of the Kamchatka Peninsula. Near Amchitka Island, Alaska, sea otter pups are hunted by bald eagles (Haliaeetus leuco-cephalus). Pups are particularly vulnerable to avian predation as they float unattended at the surface while their mothers are preoccupied with searching for food. The extraordinary buoyancy of young otter pups prevents them from readily submerging and greatly reduces their chances of escaping attack by diving.

Observations of bald eagles nabbing young otter pups from the surface of nearsliore waters confirm that eagles use a hunting strategy similar to that used when capturing large fish. That is, pups are gathered from the water in the talons of an eagle, flown to the nest location, and meticulously devoured. Studies conducted on Amchitka Island between the 1950s and 1970s found that up to 28% of the prey remains in eagle nests were from sea otters. Interestingly, some nests contain high levels of otter remains while other nests have none. This finding suggests that some individual eagles may actually specialize on hunting sea otter pups.

While terrestrial and avian predation account for only a small portion of sea otter mortality, sharks represent a more formidable and common predator. White shark (Carcharodon carcharias) attacks on sea otters along the California coast are thought to account for 8-15% of the total otter mortality recorded in this region. Curiously, there is little evidence from examination of white shark stomach contents to suggest that sea otters are actually eaten by the individuals that attack them. Instead, otters are stalked and killed by white sharks off California but are apparently abandoned prior to consumption. The absence of sea otter remains in white shark stomachs cannot be considered conclusive at this time, however, as only a small number of stomachs have been available for examination. Although other shark species are also suspected to occasionally kill sea otters, few specific details are available.

Killer whales are known predators of sea otters, but the small number of observed attacks suggests that otters are not preferred prey. Nonetheless, a substantial increase in the number of killer whale attacks on sea otters was documented between 1992 and 1996 and corresponded with a notable decline in sea otter population levels over a large part of their western Alaska distribution. It is unclear if this increase in observed killer whale attacks was due to a greater observation effort or represents a real increase in sea otter predation. If this change is merely related to increased observation effort, then killer whale predation on sea otters may not be as uncommon as previously suggested. However, if this finding represents a true increase in the rate of sea otter attacks, it may be related to the relatively recent declines of other killer whale prey, such as Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) and harbor seals (Phoca vitulina).

III. Predation on Pinnipeds

Of all the marine mammal groups, pinnipeds are probably subjected to the highest level of predation. While some pinniped species experience little or no predation pressure, others are hunted so intensively that important aspects of their natural history, including reproductive strategies, have evolved in response. Not even the largest pinnipeds such as the walrus (Odobenus rosmarus), bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus), and elephant seals (Mirounga spp.) are free from predation. Terrestrial predators of pinnipeds are particularly abundant in the subpolar and polar regions of the Northern Hemisphere, usually appearing in the form of polar bears (Ursus maritimus) and Arctic foxes (Vulpes lagopus). Southern Hemisphere ice seals are free from land predators, but instead have fierce aquatic predators such as the leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) to contend with. Pinnipeds in temperate and tropical latitudes experience reduced terrestrial predation but are subjected to increased levels of attack by aquatic predators such as sharks and killer whales. When comparing Northern Hemisphere Arctic pinnipeds to Southern Hemisphere Antarctic pinnipeds, clearly divergent predator avoidance tactics are apparent. Arctic pinnipeds escape land predators by fleeing into the water whereas Antarctic pinnipeds escape aquatic predators by retreating onto ice.

All pinnipeds require a land or ice substrate for pupping, and this facet of their natural history makes them particularly vulnerable to attack in regions where terrestrial predators are present. Golden jackals (Canis aureus), for example, are common at a Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) colony on the western coast of Mauritania and have been reported to consume freshly dead monk seals and are suspected to also prey on living pups. Freshwater pinnipeds in Russia’s Lake Baikal and in the Caspian Sea (Pusa sibirica and P. caspica, respectively) have no aquatic predators, but instead have an unusually high number of terrestrial adversaries. Wolves (Canis lupus) and eagles prey on newborn Caspian seals, and brown bears occasionally hunt Baikal seals. Ringed seal pups (Pusa hispida) inhabiting Finland’s Lake Saimaa and Russia’s Lake Ladoga are preyed upon by red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and are also suspected to suffer some level of mortality due to attacks by ravens (Corous conn), wolves, dogs, and wolverines (Gulo gulo). Similarly, brown bears, wolves, and avian predators, including eagles and ravens, sometimes also kill spotted seals (Phoca largha) in the Sea of Okhotsk. Glaucous gulls (Larus hyperboreus) and ravens may occasionally kill ringed seal pups, and gulls sometimes peck at the eyes of gray seal pups (Hali-choerus grypus), resulting in some level of mortality.

Additional terrestrial predators also hunt pinnipeds at their haul-out sites. Coyotes, for example, prey on harbor seal pups in the Pacific Northwest and are responsible for at least 16% of the pup mortality within Puget Sound, Washington. Similarly, bears and mountain lions (Felis concolor) may have historically preyed on elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris) along the California coast. In the Southern Hemisphere, mountain lions have been reported to prey on southern sea lion pups (Otaria flavescens). South African fur seals (Arctocephalus pusillus) that breed along the mainland coast of the southern Africa continent are preyed upon by brown hyenas (Hyaena brunnea) and black-backed jackals (Canis mesomelas), and South American sea lion pups (Arctocephalus australis) are probably attacked by mountain lions.

Arctic foxes have been described as hunters of small animals and birds and as a scavenger of marine mammal remains left by polar bears. However, in parts of the eastern and western expanses of the Beaufort Sea, this fox is considered an active predator of newborn ringed seal pups. In early spring, ringed seals birth and rest in “subnivean birth lairs”—ice caves complete with breathing holes constructed beneath the snow. These lairs provide both shelter from cold temperatures and protection from predators by providing a physical barrier that makes it more difficult for surface predators to detect a newborn pup. Nevertheless, foxes and polar bears enter and kill pups concealed within their subnivean homes with relative frequency. Keen olfaction allows foxes to locate lairs that may be buried under as much as 150 cm of snow. In the Beaufort Sea, Arctic foxes enter about 15% of the birth lairs present within an area. Although the annual average predation rate by Arctic foxes on ringed seal pups is about 26%, rates as high as 58% have been recorded. Ringed seals are also preyed upon by polar bears and may occasionally be attacked by red foxes, wolverines, wolves, dogs, and several avian predators. As such, ringed seals are subjected to perhaps the highest level of predation experienced by any of the marine mammals.

A. Polar Bears

Throughout their circumpolar range, the major prey of polar bears consists of pinnipeds. Polar bears are versatile predators and are well adapted for catching Arctic pinnipeds. Predation is particularly heavy on pups, as they represent an easily obtained food resource. Foraging strategies employed by polar bears range from sit-and-wait tactics to active stalking and pursuit of seals on ice and in the water. When stalking seals on ice, bears “creep” along with their heads held low, often momentarily hiding behind snowdrifts and irregularities in the ice. Despite their relative stealth and excellent ability to detect prey by olfaction, bears often have little success sneaking up on seals. Observations of bears hunting, and in at least one instance capturing, free-swimming seals in ice-free waters have also been reported. One of the sit-and-wait strategies employed by polar bears occurs while hunting ringed seals. Ringed seals forage for food under ice-covered waters throughout the winter and must therefore maintain breathing holes in which to surface. Polar bears seek out such breathing holes and often patiently await the arrival of an unsuspecting seal. When a seal surfaces in the hole for a breath of air, the bear quickly grasps it and drags it from the water onto the ice.

The ringed seal is a main staple of the polar bear diet, although in the Canadian Arctic bearded seals and harp seals (Pagophilus groenlandicus) are taken to a lesser extent. Haip and hooded seals (Cijstophora cristata) are particularly vulnerable to predation on the spring pupping grounds, where polar bears may kill more pups than can be consumed. In Alaska, most of the ringed seals attacked by polar bears are over 6 years of age, while in the Canadian Arctic it is mainly 1- to 2-year-old seals that are killed. Polar bears are largely unsuccessful hunting adult ringed seals due to their nearly constant an-tipredator vigilance. This vigilance behavior is characterized by constant head lifting and scanning of the nearby environment for the presence of predators. In late spring, polar bears enter a period of intense feeding that corresponds with the onset of the ringed seal pupping season. During this time, bears prey heavily on pups by digging into birth lairs; adult female seals attempting to protect their pups are also occasionally killed.

Walruses are occasionally preyed upon by polar bears, but this massive obobenid represents a formidable adversary quite capable of killing predatory bears. The extent of polar bear predation on walruses is not well known and is likely to vary from region to region. Walrus calves, young juveniles, and sick individuals are most vulnerable to polar bear predation. While hunting walruses, bears often cause entire hauled-out herds to “stampede” into the water by rushing toward them. Although most individuals in the stampede easily escape approaching bears, calves, or young animals may be crushed or injured in the ensuing chaos, making subsequent capture substantially easier.

B. Pinnipeds

Several pinniped species are recognized as predators of other pinnipeds and, in some locations, are responsible for a significant portion of the annual mortality incurred by regional populations. The most ferocious pinniped predators include the leopard seal in the Southern Hemisphere and the walrus in the Northern Hemisphere. In addition, several sea lion species are notorious for feeding on pinnipeds. Two types of pinniped-pinniped predation occur, one at the intraspecific level (within species) and another at the interspecific level (between species). In some cases, particular individuals (usually males) specialize in the predation of pinnipeds. For instance, young male Steller sea lions are known to prey on harbor seals off Alaska and have been noted to account for approximately 4-8% of the mortality reported for Northern fur seal pups (Callorhi-mis ursinus) at St. George Island, Alaska. Adult male Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) may also prey on other pinnipeds, as was recorded for one individual at Ano Nuevo, California, that was observed feeding on a small California sea lion (Zalophus californianus). Similarly, Southern sea lions have been observed preying on South American fur seals, and at Punta San Juan, Peru, over 8% of the fur seal pups are killed by marauding sea lions during the breeding season. Off Mac-quarie Island in the sub-Antarctic, one young male New Zealand sea lion (Phocarctos hookeri) was thought to be responsible for the mortality of 43% of the fur seal pups (Arcto-cephalus gazella and A. tropicalis) from a particular year. At the Snares Islands. New Zealand. New Zealand sea lions have also been observed to prey on New Zealand fur seal pups (Arcto-cephalus forsteri). Finally, gray seals have been reported to consume pups of their own species, but it is unclear if this represents actual predation or merely cannibalistic scavenging of beach-cast carcasses.

1. Walruses Walruses are primarily bottom or benthic feeders whose diet consists largely of bivalve mollusks, a variety of invertebrates, and fish. In addition, they also prey on marine mammals and are known to feed on bearded seals, ringed seals, spotted seals, harp seals, and young walruses. Adult and subadult male walruses are typically responsible for pinniped kills, but females in the Chukchi Sea have also been observed eating seals. Some walruses are habitual predators of other marine mammals. Individuals that regularly attack seals develop massive chest and shoulder muscles, have long and slender tusks, and their upper torsos and normally ivory-colored tusks are stained amber from consuming the oil-rich blubber of their prey. In general, walruses kill pups and young individuals, but on occasion mature adult pinnipeds are also taken. Observations of attacks on harp seal pups and bearded seals are characterized by walruses impaling the prey with their tusks. Although very little of the skeletal muscle and bone of their mammalian prey are consumed, walruses methodically devour most, if not all, of the highly caloric hide and blubber.

Only since the 1970s have reports of seal-eating walruses become common. This relatively recent phenomenon has been linked with the almost doubling of the Pacific walrus population between the 1960s and the early 1980s. Although Pacific walrus numbers are currently thought to be in decline, the nearly 20-year increase in population size certainly elevated the probability of contact between walruses and other pinniped species and may help explain the greater use of seals as a food source in the past several decades.

2. Leopard Seals The leopard seal is known to prey on penguins, sea birds, fish, squid, krill, and pinnipeds. In certain parts of their range, pinnipeds are an important part of the leopard seal diet, whereas in other areas pinnipeds are rarely taken. Leopard seals commonly hunt a variety of pinnipeds, but young crabeater seal pups (Lobodon carcinophaga) are probably the most frequently attacked and form an important part of the leopard seal diet between November and January. After January, crabeater seal pups have physically developed to the point where they are better able to escape leopard seal predation, and the rate at which they are taken declines.

Parallel tooth scars resulting from unsuccessful leopard seal attacks are quite common on crabeater seals. A study of crabeater seals in 1976 reported that 78% of 85 adult seals handled for research purposes had scars resulting from interactions with leopard seals. Fresh wounds were far more common on subadults than adults, suggesting that immature animals up to the end of their first year were most likely to be attacked, and it is thought that pups younger than 6 months are probably unlikely to survive encounters with leopard seals. The relatively high level of predation on crabeater seals is believed to represent a food source potentially more important to leopard seals than either krill or penguins.

C. Sharks

Sharks represent an important predatory threat to a variety of temperate and tropically distributed pinnipeds. It is probable that all pinniped species, with the exception of inland lake seals, experience some level of shark predation. While the extent of shark attack on pinnipeds is not understood, it is nevertheless thought to play an important role in the population dynamics, life history, and behavior of some pinniped populations. For example, the high incidence of attacks by tiger (Ga-leocerda cuvier) and white-tip reef sharks (Trianodon obesus) on Galapagos fur seals (Arctocephalus galapagoensis) is thought to have contributed to their exceptionally long 3-year period of maternal investment. It has been suggested that this extended period of maternal care reduces the amount of time pups need to spend in the water foraging, which in turn significantly reduces the risk of shark predation.

White sharks are a common predator of pinnipeds, with seals, sea lions, and fur seals regarded as preferred prey in some regions of the world because of the high lipid stores contained within their blubber. Gray seals and harbor seals are commonly hunted by white sharks off eastern Canada, and northern elephant seals, Steller sea lions, harbor seals, and California sea lions represent common shark prey in the northeastern Pacific. Southern Hemisphere white sharks focus their attacks primarily on fur seals off South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, South America, and the Galapagos Islands, but also occasionally prey on New Zealand and Australian (Neophoca cinerea) sea lions.

Off central and northern California, the diet of white sharks consists mainly of pinnipeds. In particular, white sharks are a major predator of northern elephant seals throughout their entire breeding range, with seals of all age and sex classes vulnerable to attack. A large white shark is capable of killing and consuming elephant seals weighing as much as 2200 kg and approximately 3.5 m in length.

The hunting behavior of white sharks on northern elephant seals has been well described near the Farallon Islands off northern California. White sharks typically attack elephant seals at or near the surface and usually within several kilometers of the islands. In most cases, white sharks approach their prey from below and to the rear, grasp them in their teeth and carry thein underwater, release them, and then wait for the prey to die; usually as a result of excessive blood loss. Many shark attacks are unsuccessful, as evidenced by the high incidence of shark-related lacerations and scars on the bodies and appendages of pinnipeds that escape capture (Fig. 1). The nature of these injuries suggests that when attacked from the rear, foreflipper swimming sea lions are more likely to escape than are hindflipper swimming elephant and harbor seals. Most sea lions with evidence of shark-related injuries have lower body and hindflipper injuries, whereas the majority of surviving elephant and harbor seals bear upper body injuries. While sharks sometimes inflict massively disfiguring wounds on pinnipeds, most injured seals that make it to land appear to survive. However, pregnant elephant seals that withstand shark-related injuries usually lose their pups, give birth to a stillborn, abandon the pup shortly after birth, or fail to wean the pup successfully.

In tropical regions, white sharks are less numerous and white-tip reef, gray reef (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos), and especially tiger sharks represent the major pinniped predators. Tiger sharks hunt monk seals (Monachus schauinslandi) of all ages off the northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Although other predators like hammerhead (Sphyrna sp.) and mako (Isurus sp.) sharks also occur off northwestern Hawaii, they apparently do not attack monk seals with any regularity. Gray reef sharks are frequently present when tiger sharks kill monk seals, but their presence is thought to represent scavenging rather that direct predation.

Figure 1 Northern elephant seal with a shark-inflicted wound near the hindflippers.

A high number of monk seals bear shark-inflicted wounds and scars, indicating that not all predatory attacks are successful. Adult male monk seals seem to have the highest incidence of scarring, suggesting that animals of other age classes are less likely to survive attack. Highly scarred males may also be attributed to the elevated aggressiveness in males during the breeding season and their propensity to attack or chase approaching tiger sharks. In addition to direct kills of monk seals, the severity and timing of nonfatal injuries to individual females may reduce overall reproductive success. Field observations confirm that female monk seals suffering major, but nonfatal, shark-related injuries have shorter mean lactation periods and overall lower pup survival. It has been suggested that the combination of lethal and nonlethal tiger shark attacks on Hawaiian monk seals may be hindering the recovery of this endangered population.

Pinnipeds (and cetaceans) are regularly tormented by a diminutive pest called the cookie-cutter shark (Isistius brasiliensis). This small squaloid shark ranges in size from 14 to 50 cm and inhabits deep tropical and subtropical waters of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. By use of rasping jaws and teeth well suited to cutting, cookie-cutter sharks attach themselves to their marine mammal victims and remove small circular plugs of skin and blubber. Although these attacks are nonlethal, they represent a peculiar form of predation that falls outside the definition set forth at the beginning of this article, but is nevertheless of importance to recognize.

D. Killer Whales

The diet of killer whales varies considerably between and within geographic regions. Some forms of killer whales, termed “transients,” are mammal eaters, whereas others, termed “residents,” base their diet on fish. Mammal-eating killer whales have been observed to hunt at least 14, and are suspected to take as many as 24, species of pinnipeds. With the exception of inland lake seals and monk seals (Monachus spp.), all pinniped species probably endure some level of killer whale predation.

Pinnipeds comprise a substantial part of the diet for some transient killer whale populations, and observations of predatory events have been witnessed in a variety of locations from around the world. In subpolar and polar areas, where killer whales are most abundant, reports of attacks on pinnipeds are particularly common. Killer whales attack pinnipeds in both offshore and nearshore regions and often in close proximity to terrestrial haul-out sites (Fig. 2).

Of all the pinniped species hunted by killer whales, southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonina), southern sea lions, harbor seals, Steller sea lions, walruses, and California sea lions have been recorded most commonly as prey species. Approximately 62% of the transient killer whale attacks observed since the mid-1970s off British Columbia and Washington have been on harbor seals. Harbor seals are particularly abundant in this part of the world and appear to be relatively easy prey for killer whales to capture and kill, perhaps accounting for the apparent dietary preference on this pinniped species. Steller sea lions, which account for about 7% of all observed attacks, are far more difficult to capture, and the large size obtained by adult males combined with their pronounced canines make attack potentially more dangerous. Other less frequently taken pinniped prey include California sea lions and northern elephant seals.

Figure 2 Killer whale patrolling a harbor seal haul-out site.

Pinnipeds are attacked by lone killer whales and by groups ranging in size from 2 to 30 or more, but the majority of reported attacks are by pods of 10 or less. Killer whales have often been referred to as “pack hunters” because of their tendency to often forage cooperatively and employ coordinated maneuvers to capture mammalian prey. A well-described example of this coordination was witnessed in the Antarctic, where a group of killer whales was observed to work together to generate a wave large enough to sweep a crabeater seal off an ice floe and into the water so that it could be captured.

Killer whales use a variety of strategies to kill pinnipeds, including ramming them with their rostrums or heads, flinging seals and sea lions high into the air with an abusive slap of their tail flukes, and violently shaking prey while grasped tightly in their mouths. Transient killer whales employ great stealth and remain silent while hunting so as not to announce their presence to potential prey. Although transients typically hunt for prey near to shore where they are hidden by wave action and turbulence, they are also capable open water foragers. When whales encounter potential prey in open water, one observed hunting strategy is for group members to take turns rushing the prey and striking it with their flukes or ramming it with their heads. Once killed, the pinniped prey is shared among group members, similar to the food-sharing behavior observed in social carnivores such as lions and wolves.

At Peninsula Valdes, Argentina, and on Possession Island in the Crozet Island Archipelago, killer whales intentionally strand themselves in an effort to hunt sea lions and elephant seals that are on or near the beach. Southern seal lions and southern elephant seals are hunted off Peninsula Valdes, whereas on Possession Island, whales typically take newly weaned southern elephant seal pups. In general, pups and small adult seals are most vulnerable, but adults are also occasionally killed. Once a seal or sea lion has been captured from the beach or nearshore area, it is usually held in the mouth of a killer whale by one of the flippers or taken crossways in the mouth and shaken vigorously. Sometimes, captured pups are exchanged between members of the killer whale pod. Intentional stranding behavior also occurs in the absence of prey, suggesting that adult killer whales may actually teach their youngsters the finer aspects of this foraging strategy.

IV. Predation on Cetaceans

Although killer whales and sharks are responsible for most attacks on whales, dolphins, and porpoises, other cetaceans such as false killer whales, pygmy killer whales, and pilot whales also represent a potential predatoiy threat. In addition to these aquatic predators, one terrestrial predator, the polar bear, successfully hunts beluga whales (Delphinaptertis leucas) and narwhals (Monodon monoceros) in Arctic areas. River dolphins appear to be the only cetacean group free from natural predation, although it has been suggested that freshwater caiman in South America may occasionally take young dolphins. Finally, killer whales are likely to experience little or no mortality related to predation.

A. Blackfish

Three members of the delphinid family, including the false killer whale, pygmy killer whale, and short-finned pilot whale, are thought to be hunters of other cetaceans. Each of these species has teeth and jaws suitable for killing and handling large mammalian prey, and all have been observed to at least occasionally prey on other dolphins. Of these three “blackfish,” the false killer whale is best known for attacks on small pelagic dolphins and also has a record of harassing humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae) and sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus). A series of observations, mainly by marine mammal observers onboard purse-seine boats fishing for yellowfin tuna in the eastern tropical Pacific, have detailed false killer whale attacks on pantropical spotted and spinner dolphins (Stenella attenuata and S. longirostris). Although nearly two dozen attacks were recorded, false killer whale predation on cetaceans outside of the eastern tropical Pacific is rare, suggesting that the high incidence of attack on the yellowfin tuna grounds may be site and circumstance specific. That is to say, false killer whales may be utilizing a prey resource related to tuna fishing operations (i.e., dolphins being released from temporaiy capture in fishing nets) that is unavailable outside of the eastern tropical Pacific.

Large whales, such as sperm whales and humpback whales, are also subjected to predatory advances by false killer whales. A school of false killer whales has been observed harassing a sperm whale group off the Galapagos Islands. In this event, no sperm whale mortality was recorded, but the false killer whales did inflict at least superficial injury to several individuals and elicited noticeable fear reactions. Similar, albeit uncommon, events have also been suggested for interactions between false killer whales and humpback whales.

Pygmy killer whales have also been observed in predatory attacks on small dolphins during fishery operations in the eastern tropical Pacific, although observations of this nature are less common than those recorded for false killer whales. The predatory habits of pygmy killer whales on other cetaceans are poorly understood. In captivity, this species has been implicated in the death of a young pilot whale and a dusky dolphin (Lagenorhijnchus obsairus), but it is unclear if these events led to consumption of the victim.

Similarly, few records regarding pilot whale predation on other cetaceans are available. Although pilot whales are not generally known to prey on marine mammals, records from the eastern tropical Pacific suggest that this species does chase, attack, and may occasionally eat dolphins during fishery operations. The incidence at which these predatory events occur, however, is very low. In captivity, pilot whales have been noted to eat stillborn and young dolphins. Short-finned pilot whales have been observed harassing sperm whales in the Gulf of Mexico and off the Galapagos Islands, and although such harassment has been observed to be nonlethal, these events nevertheless often elicit a pronounced fear response, called a “marguerite formation” by sperm whale groups. The marguerite is a defensive formation in which group members form a heads-in and tails-out circular arrangement resembling the petals of a flower. By placing the powerful flukes, a source of potential danger for predators, toward the outside and containing particularly vulnerable individuals, such as calves, on the inside of the formation, sperm whales can usually defend themselves from harm. This marguerite response has also been noted for sperm whale groups under lethal attack by killer whales and when being hunted by whalers. Therefore, the formation of a marguerite in response to pilot whale harassment suggests that sperm whales do at times appear to be threatened by this species. It remains unclear, however, if such harassment by pilot whales represents actual predatory intent or if such interactions are merely practice hunting attempts or social play.

As suggested by the accounts presented here, interactions of false killer whales, pygmy killer whales, and pilot whales with other cetaceans are not particularly common. Of the lethal attacks recorded to date for each of these three blackfish species, all have been in relatively unnatural situations. That is, attacks have occurred either in captivity where species that might normally avoid each other are maintained in the same confines or centered around the eastern tropical Pacific tuna fishing operations where smaller dolphins may become available prey due mainly to capture fatigue. Therefore, it is difficult to assess the regularity of marine mammal predation by these several species, and the scarcity of observed predatory events suggests that marine mammal prey is likely to be secondary to an otherwise fish-and squid-based diet.

B. Sharks

Sharks represent a significant predatory threat to some populations of dolphins. Crude estimations of predation rates, as determined by the proportion of dolphins within a study population possessing shark-inflicted scars and injuries, vary greatly. Shark-related scars on odontocetes are particularly notable for some populations, whereas others go seemingly untouched.

Results from several long-term photoidentification studies of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus and T. aduncus) have documented shark bite scars rates as low as 1% off southern California, an intermediate rate of 22% in western Florida, and up to about 37% off eastern Australia. The frequency of scars may also vary for different dolphin species within the same region. For example, off South Africa, where humpbacked dolphins (Sousa chinensis) and bottlenose dolphins overlap in distribution and habitat use, the former species has substantially more scarring related to shark attack than the latter.

Interestingly, the proportion of individuals bearing crescent-shaped shark bite wounds is considerably higher for nearshore species than it is for their offshore counterparts. This apparent discrepancy may be attributable to a variety of factors. To date, most long-term studies on dolphin populations have been conducted nearshore, increasing the opportunity to observe shark scarring. Alternative explanations include the idea that predation on oceanic dolphin is less common overall or that shark attacks in the open ocean are generally more successful. One theory that may at least partially explain why nearshore dolphins have higher rates of scarring is related to habitat features. The habitat of nearshore cetaceans offers a variety of “cover” features, such as kelp and surf, which may make escape from a predator more successful, whereas oceanic species have no such cover and depend solely on fleeing or the protection offered by conspecifics within their social group to escape fatal attack.

Tiger sharks, dusky sharks (Carcharhinus obscurus), white sharks, and bull sharks (C. leucas) are most often implicated in attacks on nearshore dolphins and porpoises. Other sharks, including oceanic white tip and hammerhead sharks, have also been observed to occasionally attack dolphins. Tiger sharks are notorious predators of spinner dolphins off the Hawaiian Islands, whereas white sharks prey on a variety of odontocetes, ranging in size from the small harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) to more substantial beaked whales, and perhaps even newborn mysticete whales. Evidence of shark predation on baleen whales is relatively uncommon, but a report of a tiger shark attacking a young humpback whale has been recorded. Similarly, large sharks (and killer whales) were observed circling a group of sperm whales in which one adult female was giving birth, but no direct attack was noted. Although the number of observations regarding shark attack on large whales is few, it is reasonable to assume that some predatory events probably do occur at least occasionally.

While predation by sharks is of particular concern for cetaceans in the tropics and subtropics, attacks in other regions also occur. The remains of a complete southern right whale dolphin (Lissodelphis peronii) fetus as well as the genital region of an adult female were found in the stomach of a sleeper shark (Somniosus pacificus) off coastal Chile. In addition, Greenland sharks (S. squamulosus) have been reported to prey upon narwhals in the eastern Canadian Arctic, and franciscana dolphins (Ponotoporia blainvillei) have been found in the stomachs of seven-gilled (Heptranchias perlo) and hammerhead sharks off Brazil. While each of these accounts is suggestive of predation, they should be considered with caution, as it is unclear if the aforementioned sharks actually attacked living dolphins or if the remains identified from stomach content analyses were attributable to scavenging.

C. Polar Bears

Although pinnipeds are the principal marine mammal prey of polar bears, they also actively hunt and occasionally consume narwhals and beluga whales. Polar bears off western Alaska, for example, have been observed “fishing” beluga whales and narwhals out of small openings in the ice (Fig. 3), sometimes killing numbers far greater than can possibly be eaten. In one particular event, polar bears killed and dragged onto the ice at least 40 ice-entrapped beluga whales, and in a similar episode, a single male polar bear was seen to successfully capture 13 beluga whales from a small opening in the ice over a short period of time.

Beluga whales regularly swim into extremely shallow estuary and river channel areas. On rising tides, whales penetrate far into rivers and creeks, often moving into waters so shallow that they can rest on the bottom while a considerable portion of their body remains above the surface. This behavior can sometimes result in partial stranding, but the animals are typically able to free themselves. On occasion, however, complete stranding occurs accidentally, during which time individual belugas remain beached until the return of the incoming tide. At least some beluga whale mortality results from polar bears feeding on stranded individuals. In addition to opportunistic foraging on temporarily beached whales, individual bears have been observed wading into shallow waters and chasing whales passing near to shore. Predatory polar bears also actively stalk free-swimming belugas from ice edges. In this situation, bears either roam along the ice edge or remain motionless while awaiting a group of beluga whales to move within striking range. When a whale passes near enough, a polar bear will launch itself from the ice and onto the back of the unsuspecting beluga. In one incident, a single polar bear was observed to use this hunting tactic to capture and kill two beluga whale calves within 24 hr. This hunting technique requires that bears time their jumps accurately and, more amazingly, handle and debilitate their prey in an aquatic medium. Further, once dead, the beluga must be pulled from the water and dragged onto the ice. In cases where this hunting technique has been observed directly, the captured belugas are generally young, smaller individuals.

Figure 3 Polar bear hunting beluga whales.

Polar bears have also been observed to attempt attacks on belugas while swimming in pursuit of them. Thus far, no successful attacks have been documented for this aquatic hunting tactic, and on at least one occasion, a group of belugas was seen to chase a polar bear out of the water with group-coordinated threat behavior including tail lashing and repeated close approaches toward the swimming bear. Aquatic stalks by polar bears are largely unsuccessful due to the greater mobility and speed of whales in the water. In fact, the willingness of belugas to closely approach bears in the water, either out of curiosity or in a possible attempt to harass them, suggests that they have little fear of this predator when it is waterborne.

In contrast to the inshore habits of beluga whales, narwhals prefer deeper water and are commonly sighted in considerable numbers offshore of beluga groups in the eastern Canadian Arctic. Polar bear predation on narwhals has been observed rarely, with the few attacks reported consisting of narwhals stranded on tidal flats or entrapped by ice. In one incident, three adult female narwhals stranded on a tidal flat were consumed by a single polar bear. All three of the narwhals bore extensive claw marks and their blubber had been stripped dor-sally from the head area back to the tail stock.

D. Killer Whales

In addition to pinnipeds, dugongs, and sea otters, mammal-hunting killer whales (termed transients) also prey upon a variety of dolphins and porpoises, and even occasionally attack sperm and baleen whales. Transient killer whales are relentless hunters, spending up to 90% of each daylight period searching for food. In addition to marine mammal prey, terrestrial animals such as deer (Odocoileus hemionus) and moose (Alces dices) are also taken occasionally. In these cases, killer whales opportunistically intercept individual deer and moose as they swim between coastal islands.

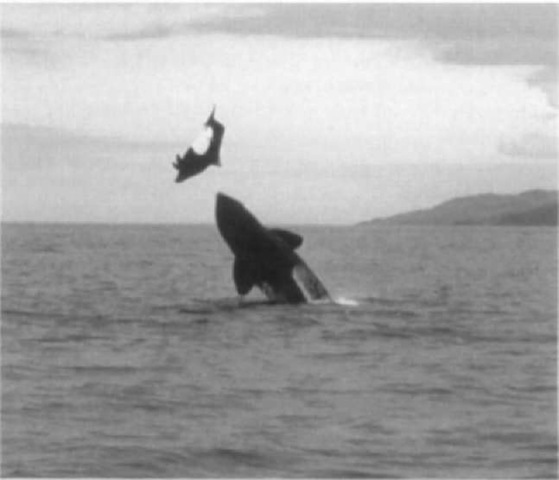

More than most other marine mammals, killer whales are social hunters, often working together to capture prey in a coordinated manner resembling that of pack-hunting social carnivores such as hyenas, wolves, and lions. Transients typically form slightly larger groups while hunting dolphins and porpoises, as compared to group sizes observed during pinniped attacks. Most hunts of small cetaceans have some component of chase, making more individuals necessaiy to prevent prey escape. Sometimes these high-speed chases result in a killer whale leaping free from the water with a dolphin or porpoise in its mouth. When dolphin prey are assembled in relatively large schools, killer whales often attempt to separate one or a few individuals from the group before commencing active pursuit. Once a prey item becomes exhausted, killer whales then attempt to kill the animal by breaching onto it, ramming it from below, tossing it into the air, or grasping it in their teedi (Fig. 4).

A variety of dolphins and porpoises are hunted by killer whales. Off New Zealand, common dolphins (Delphinus del-phis) are attacked most commonly, but bottlenose dolphins and dusky dolphins (Lagenorhijnchus obscuriis) are also hunted. Stomach content analysis of a stranded killer whale off southern Brazil found the remains of three franciscana dolphins. In the Gulf of Mexico, a pod of killer whales chased and killed a pantropical spotted dolphin, and Pacific white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhijnchus obliquidens), Dall’s poipoise (Phocoenoides dalli), and harbor porpoises are some of the more commonly hunted small cetaceans off the west coast of North America. In addition to these relatively small cetaceans, larger prey, including northern bottlenose whales (Hyperoodon ampullatus) and long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas), are also hunted occasionally by killer whales. In Arctic waters, killer whales sometimes herd beluga whales into shallow inlets and creek openings where they then rush into the group to capture young animals. Further, killer whales have been seen feeding on beluga whales and narwhals in open waters and on animals trapped by sea ice.

Figure 4 Killer whale attacking a Dall’s porpoise.

An interesting study of contrasts exists for transient killer whales off British Columbia and in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Although transients in both regions feed exclusively on marine mammals, harbor seals are the most common prey item of whales off British Columbia, whereas transients in Prince William Sound prey about equally on harbor seals and Dall’s poipoises. Low harbor seal abundance in Prince William Sound may account for the apparent preference for porpoise prey in this region.

Although killer whales tend to focus their predatory attentions on pinnipeds and small odontocetes, numerous reports of attacks on sperm whales have also been recorded. In most cases, the sperm whale groups being attacked contained one or more calves. Sperm whales are likely to be difficult for killer whales to kill, as they are excellent deep divers and can escape predation by descending to depth, possess sizable teeth capable of inflicting significant injuries, and actively defend group members when threatened. Regardless of the difficulty in hunting sperm whales, field observations from the Pacific noted killer whales successfully killing at least one adult member of a sperm whale group and fatally injuring at least several others.

Killer whales have been noted to hunt all of the mysticete species except lor pygmy right whales (Capcrea marginata), but observations of attacks on baleen whales are not common. As is true for sperm whales, baleen whales are also difficult to kill, requiring extended elfort and coordination between pod members. A typical strategy employed by killer whales during large whale hunts consists of first fatiguing the prey by active pursuit, followed then by delivery ol a debilitating attack. It has been suggested that attacking killer whales may grasp large whales by the flukes and pectoral flippers in an attempt to slow or stop their movement or perhaps drown their prey by pulling them underwater.

In the Gulf of California, researchers watched from a small airplane as a group ol 15 killer whales attacked and killed a Bryde’s whale (Balaenoptera edeni). During this event, the killer whales repeatedly swam onto the back and head ol the Bryde’s whale, a behavior speculated to be useiul in hindering life-sustaining respiration of the animal under attack. A similar incident was recorded oil British Columbia where killer whales were observed to exhaust and kill a fleeing minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata). Humpback whales are also attacked by killer whales, but unlike the more passive escape tactics employed by some oi the other mysticetes, humpbacks deiend themselves aggressively from killer whales by thrashing at them with their tail flukes and flippers.

Of all the mysticetes, gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) are probably most frequently attacked by killer whales. On an almost predictable basis, gray whales are attacked by “California” killer whales in Monterey Bay each April and Mav (Fig. 5). Young calves making their first northward migration are particularly vulnerable, even while under the watchful eye oi their mothers. Records irom beach cast gray whales along the coast of the Chukchi Sea show a similar pattern to that observed off California; whales with the highest incidence of killer whale-induced injuries (i.e., tooth scarring) were generally under 10 m long, suggesting that killer whales in this region also select young gray whales as their primary predatory target.

Figure 5 Killer whale attack on California gray whales.

Figure 6 Young western gray whale with evident killer whale tooth scarring.

Direct observations of killer whale attacks on large whales are relatively few, but several lines of evidence suggest that predatory interactions may occur more often than suspected. The presence of killer whale tooth rakes on the bodies, flippers, and flukes of many large whales can reach remarkably high proportions (Fig. 6). Photoidentification studies on humpback whales off Newfoundland and Labrador in the north Atlantic found that 33% of the individuals identified had killer whale-inflicted tooth rakes on their bodies. Scars on the flukes oi 20-33% oi humpback whale calves suggest that predation may be focused on young animals. A similar pattern has also been observed for western gray whales in the Sea of Okhotsk, where nearly 34% oi all whales pho-toidentified possess killer whale tooth rakes. In this case, the western gray whale is highly endangered, making any level of killer whale predation a potentially important source oi mortality. Bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) from the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Sea populations have relatively low rates or killer whale tooth scarring, ranging from about 4 to 8% of the observed individuals. In contrast, 31% oi bowhead whales in the Davis Strait population show evidence of scars from killer whales.

The relatively high incidence of killer whale tooth scarring on some regional populations oi large whales suggests that predatory attempts are probably more regular than indicated by field observations alone and that many attacks are unsuccessiul. Tooth rakes may not be truly indicative oi predation attempts by killer whales, however, but may instead represent capture practice or instruction of predatory techniques for younger members of the pod. Finally, rake marks may also result from killer whales testing large whales to assess the presence oi particularly vulnerable individuals that may be separated easily from a group and killed.

Although killer whales exert considerable time and energy in pursuit and capture of large whales, they consume relatively little or their victims. Reports from whaling ship logbooks and more recent field observations suggest that killer whales often preierentially consume only the tongue, lips, and portions of the ventrum of large whales before abandoning them. This phenomenon is little understood and stands in stark contrast to the behavior of terrestrial predators that consume all or most of their mammalian prey.

E. Humans

A review of predation on marine mammals would be incomplete without some mention of humans as predators. No other predator has the ability to harvest marine mammals at the same rate or intensity as humans. While killer whales or polar bears may take tens of animals over relatively short periods of time, humans are capable of sometimes killing hundreds of individuals within hours. Although the ecology of the world’s oceans is in part maintained by predator-prey interactions, human exploitation of marine mammal populations can have devastating consequences.