Hippopotamuses are stocky, large, semiaquatic, hoofed mammals that are classified as members of the family Hippopotamidae (order Artiodactyla). There are two extant species. The endangered pygmy hippopotamus, Cho-eropsis liberiensis, inhabits the dense forests of western Africa. The much larger common hippopotamus. Hippopotamus am-phibius (see Fig. 1), has a broader geographic range that includes manv of the water systems of sub-Saharan Africa.

I. Anatomy and Behavior

Due to its secretive nature, field observations of the pygmy hippopotamus are rare, so little is known of the ecology and natural history of this species. The animal is knockwurst-shaped, weighs approximately 150-250 kg. is basically hairless, and has a broad muzzle with prominent canine teeth. Choeropsis is thought to be more solitary and less aquatic than Hippopotamus.

Figure 1 Possible phylogenetic relationships among Cetacea (top) and artiodactyl ungulates—hippopotamuses (middle) and ruminants (bottom). Molecular data support the relationship on the left, and gross anatomical comparisons imply the relationship on the right. Molecular data suggest that cetaceans and hippopotamuses share aquatic specializations that may be further evidence of their close phylogenetic kinship.

The huge common hippopotamus ranges in size from approximately 1000 to 3500 kg. Like the pygmy hippopotamus, Hippopotamus amphibius is nearly hairless. The skin lacks sebaceous glands and is underlain by a thick layer of insulating fat. The limbs are short and stubby, and the skull is huge with the orbits and nostrils positioned dorsally. Hippopotamus individuals spend a large proportion of their lifetimes in rivers, lakes, or swamps. They are capable swimmers and are able to stay submerged for over 5 min. At dusk, the common hippopotamus advances to the land to graze on grasses and at dawn returns to the safety of the water to loll about, digest, and rest. H. amphibius is highly gregarious and, under some environmental conditions, this species concentrates into large herds of over 100 individuals. Groups of 10 to 20 animals are more typical. The males are territorial and battle viciously when competing for mates, but a variety of ritualized social behaviors limit intermale conflicts to some degree. Because of their enormous size and dangerous gape, adult common hippopotamuses have few natural enemies beside humans.

II. Fossil Record

The paleontological record of Hippopotamidae is quite rich in the Pleistocene and the Pliocene, the last five million years of geologic history. In fact, during some time intervals, five or more hippopotamid species were contemporaneous. The geographic distribution of hippopotamids was also more extensive in the not so distant past; hippopotamids ranged into Europe, Asia, North Africa, and Madagascar. In the Pleistocene, there were hippopotamuses in Great Britain! So the current complement of two extant species is a mere relic of past hippopotamid diversity.

Despite their relative abundance in the Plio-Pleistocene, definitive hippopotamids only extend back into the fossil record approximately 15 million years. The earliest described genus, Kenyapotamus, is found at several localities in East Africa (Pickford, 1983), but the evolutionary history of hippopotamids prior to 15 million years ago is obscure and may only be illuminated by further fossil discoveries.

III. Phylogeny of Hippopotamids

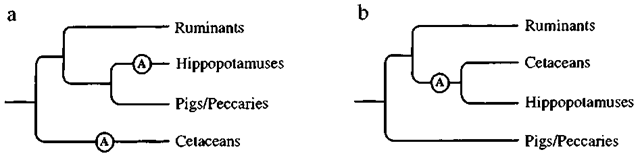

Semiaquatic hippopotamuses are not classified as marine mammals, the main focus of this topic. However, hippopotamuses recently have been implicated as close evolutionary relatives of cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) and are thus relevant to this volume. The phylogenetic origins of Hippopotamidae are not clearly characterized, but among living species, mammalogists have traditionally aligned hippopotamuses closest to pigs and peccaries with ruminating ungulates (cattle, antelopes, deer, giraffes, chevrotains, and camels) considered their next closest evolutionary kin (Fig. 2a; Gentry and Hooker, 1988 and references therein). Based on morphological similarities, hippopotamuses and these other hoofed mammals are classified as members of the mammalian order Artiodactyla, even-toed ungulates. Hooves in which the axis of symmetry runs between the third and fourth digits, the so-called paraxonic condition, characterize all species in this group.

Figure 2 Tivo phylogenetic hypotheses of hippopotamus origins that have different implications for the evolution of aquatic features. Acquisitions of aquatic traits shared by hippopotamuses and cetaceans are represented by open circles with “A” inside, (a) If hippopotamuses group within Artiodactyla, even-toed ungtdates, and are only distantly related to Cetacea, aquatic specializations were derived independently in hippopotamuses and whales, (b) If cetaceans are the closest living relatives of hippopotamtises, shared aquatic specializations of these taxa may have been acquired only once in their common ancestors.

According to the majority of the gross anatomical evidence, cetaceans are only distantly related to hippopotamids (Fig. 2a). Therefore, the common aquatic specializations of cetaceans and hippopotamuses traditionally have been interpreted as convergences. In this case, independent adaptation to an aquatic environment was hypothesized to have driven the parallel evolution of grossly similar characteristics, such as near hairlessness, a thick layer of insulating fat, the lack of sebaceous glands, the lack of scrotal testes, and the ability to nurse offspring underwater. These features are common to all extant cetaceans and one or both extant species of hippopotamus.

Recently, a radically different interpretation of hip-popotamid phylogeny has been presented. Examination of diverse genetic data suggests that cetaceans, not other artio-dactyls, are the closest relatives of hippopotamids (Fig. 2b; Gatesy, 1998; Ursing and Arnason, 1998; Nikaido et al., 1999). In this scheme, whales are simply highly derived members of “Artiodactyla.” Therefore, at least some of the common aquatic specializations of hippopotamuses and whales could be interpreted as further evidence of a close evolutionary relationship between these mammals (Fig. 2b). The recent discovery of fossil whales with fully functional hindlimbs and paraxonic feet lends further credibility to close phylogenetic ties between whales and artiodactyls. If genetic data portray an accurate picture of hippopotamid origins, the seemingly ungainly hippopotamus may offer additional clues to the evolutionary derivation of the most graceful of marine mammals, the cetaceans (Fig. 2).