Except for the polar bear (Ursus maritimus), all marine mammals feed exclusively in aquatic environments, and mostly in the world’s oceans. The depths at which they hunt for and capture prey and the time spent submerged vary among pinnipeds, cetaceans, sea otters, and sirenians as a function of physical and physiological adaptations among these taxa, environmental conditions (e.g., coastal or pelagic, tropical or polar, season), and body size, age, and health of individuals. All are ultimately tied to the sea surface to periodically breathe, yet natural selection has operated to minimize the time needed there and to maximize the amount of time that may be spent submerged hunting and capturing prey. What has become known in recent years is that these animals spend substantial parts of their lives moving within the water column to relatively great depths and some over vast geographic areas in search of food. Among the amphibious pinnipeds, these aquatic foraging bouts may extend, with minor interruptions, for several weeks to several months, punctuated by periods of several days to weeks on land or ice when no feeding occurs when these animals rest, molt, or breed. For the less amphibious sea otters (Enhydra lutris), diving and foraging periods may be separated by periods spent sleeping or resting at the sea surface rather than on land. Among the wholly aquatic cetaceans and sirenians.

Foraging bouts may last several hours or perhaps days, interrupted by periodic resting periods at the sea surface. Individuals of some species, particularly sperm whales and many mysticete cetaceans, may fast during migrations or in particular breeding areas. Although the diving performance and the patterning of individual dives or sequences of dives vary among species, what has become apparent for all marine mammals is that little time is spent at the surface between successive dives to exchange gases (i.e., unload carbon dioxide from tissue and blood and and restore tissue oxygen stores). This allows for sustained, repetitive diving and hunting, and is made possible bv physiological adaptions for conserving heat and oxygen and by anatomical adaptations that promote effective movement in the aquatic environment (e.g., reducing drag through streamlining and efficient propulsion mechanisms).

I. Methods of Studying Diving Behavior

The simplest method for studying the diving behaviors of marine mammals is direct observation of the timing and location of appearances of individuals at the sea surface, the number of breaths taken there, and the duration of the animal s disappearance under water before reappearing. With some assumptions and strong inference, much can be deduced about what animals are doing while hidden beneath the ocean surface. Indeed, most early knowledge of diving, feeding, traveling, and migratory behaviors was based on such interpretations.

Other techniques for documenting diving behavior have used radio transmitter and telemetry instruments, operating at different radio frequencies. Sonic transmitters, operating at relatively low frequencies or wavelengths, allow the tracking of animals when they are submerged by placing a microphone (hydrophone) beneath the sea surface to listen for and orient to these signals (Fig. 1). Higher frequencies are used for in-air detection and tracking but generally yield less detailed observations, mostly when an animal reached the surface and how long it spent there. Durations are inferred from periods of radio silence, as transmissions that occur when the animal is submerged will generally be reflected downward from the sea surface and so not be capable of detection in air. When vocalizing underwater, some marine mammals mav also be tracked with hydrophones to detect and localize those sounds. All of these techniques require constant tracking and observers must be within a few hundred meters (surface observers) or kilometers (observers in aircraft), as the signals attenuate quickly.

During the past several decades, and in particular during the 1990s, an enormous amount of information has been added to those simple observations due to technological developments and their application to free-ranging marine mammals. For example, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, an encapsulated mechanical photographic device was used in the Antarctic to study the diving patterns of Weddell seals (Leptonychotes weddellii). That instrument provided a continuous trace on photographic film ol the depth of the seal versus time. The spooled film was pulled at a known rate past a small radioactive particle, which rested on a pressure-sensitive aim. Thus a two-dimensional record was made on the film of depth versus time. From these records came the first long-term (about 7 days continuous, based on film capacity) data on the vertical movements of marine mammals in the open ocean. Those instruments, called time-depth recorders (TDRs), were later deployed on a number of species of fur seals and some sea lions to study the effects of variation in body size and environment on the foraging patterns of lactating females. However, because the instruments were rather large and because they were attached with harnesses, tliev likely had some influence on the recorded durations of dives because of the effects of drag on swimming that they imposed, particularly for fur seals. Other simple instruments used capillary tubes with pressure sensors attached to record the maximum depth of a single dive or the maximum depth achieved during a period of diving.

Figure 1 A sonic tag glued to the pelage of an adult male Weddell seal for monitoring its underwater movements in McMurdo Sound, Antarctica.

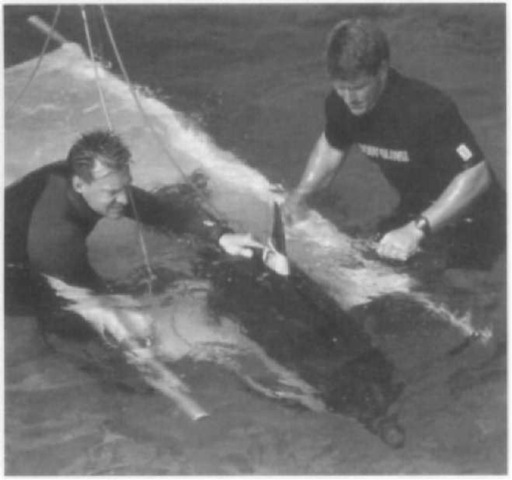

Mechanical instruments were replaced in the late 1980s with much smaller electronic instruments, armored to keep seawater out under extreme hydrostatic pressures. These instruments could collect and store substantially more data on depth and duration of dives and also had less impact on behavior. Indeed, today most of these instruments weigh less than 50 g and can be glued (Fig. 2) to the hair or fur of pinnipeds for long-term (up to a year) monitoring, attached to the dorsal fin of small cetaceans (Fig. 3), attached to the skin surface with subdermal anchors (Fig. 4) or deeply embedded into the blubber of large whales, or attached with suction cups to the skin ol cetaceans for shorter term (up to several days) study. Because these instruments may now also collect data other than just water depth as a function of time (e.g., swim speed, ambient light level, compass bearing, seawater temperature, salinity), they are called time-data recorders. These instruments are generally controlled bv small microprocessors that can be programmed to record measures of various parameters at particular intervals that are then stored in electronic memory for several months or more. Thus, detailed records (e.g., at 1-sec intervals) of a marine mammals position in the water column, in addition to other environmental and behavioral data, can be collected continuously for months or more.

Figure 2 A satellite-linked radio transmitter (PTT) attached to the head of a southern elephant seal at Marion Island.

Even more recently, technological developments and improvements have involved remote sensing of diving patterns and geographic movements of marine mammals using radio transmitters that communicate with earth-orbiting satellites, most notably the two polar orbiting satellites of the ARGOS

Figure 3 A satellite-linked radio transmitter (PTT) attached to the dorsal fin of a short-beaked common dolphin.

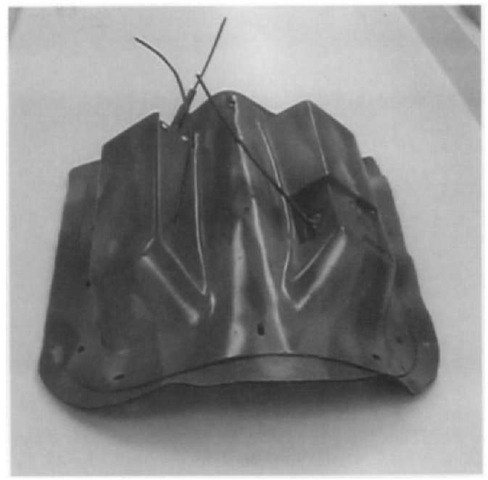

Figure 4 A saddle package with a satellite-linked data recorder and transmitters custom built for attachment to the skin surface of a California gray lohale.

Data Collection and Location (DCLS) system. These transmitters are known as platform transmitter terminals (PTTs). They allow animals to be located several times each day. They also allow small amounts of behavioral and environmental data to be transmitted through the DCLS. Further continuing improvement and miniaturization of film and digital video equipment are allowing the underwater diving, social, and hunting behaviors of marine mammals to be visually documented.

Most of what is now known and summarized below on the diving behaviors of marine mammals is based on two-dimensional (depth versus time) data from electronic TDRs, which are occasionally supplemented by geographic locations of the animals at the sea surface. Almost nothing is known of the movements of these animals in three-dimensional ocean space beneath the sea surface. Nevertheless, the seductiveness of representations of a single spatial vector (depth) versus time as a trace in a two-dimensional, linear spatial format led some researchers to infer the geographical form of dives in three-dimensional space. Moreover, some researchers further assigned physiological and behavioral function to those inferred spatial forms. However, die validity of such inferences and conclusions of function is untested, although they are interesting hypotheses for further rigorous inspection.

A substantial amount of information was collected on diving patterns of a number of pinniped species in the 1990s compared to relatively little progress in die study of cetacean diving patterns. The primary reason for the difference in quantity and quality of data between these taxa is principally due to the greater difficulty of keeping instruments attached to cetaceans compared to the long-term attachment of instruments, up to one year, to pinnipeds by gluing them to their hair.

Regardless, the dive patterns of virtually all species were limited to particular times of the year and even to particular classes of individuals (e.g., lactating female pinnipeds). Nearly year-round monitoring of northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris) has been the exception. Consequently, any discussion of diving patterns is conditioned on these important constraints. Moreover, whether hunting or feeding occurs whenever animals are submerged and diving has not been confirmed. The incorporation of additional environmental and physiological sensors to TDRs and PTTs will undoubtedly help refine studies of diving patterns to more rigorously evaluate spatial form and function of subsurface movements and to enhance the summaries of dive patterns presented here.

II. Pinnipeds

A. Otariids

California sea lion females (Zalophus californianus) dive mostly to depths of around 75 m for about 4 min during summer and then deeper and longer the rest of the year (maximum depth of 536 m and longest dive of 12 min). When at sea for several days at a time and up to 1 to 2 weeks at some seasons, California sea lions dive virtually continually and rest at the surface for only about 3% of the time.

Juvenile Steller (northern) sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) dive to average depths of 21 m (maximum 200 in). Most dives last less than 1 min. They are generally shallower at night and deeper in spring and summer than in winter. Adult females dive deeper than juveniles. Dives are deeper in winter than in autumn.

Southern sea lions (Otaria flavescens) dive mostly at night, apparently to the sea bed, where they hunt at depths down to 250 m. While at sea near the Falkland Islands, these sea lions dive virtually continually. Near Patagonia, over half of the time that lactating females are at sea they are diving. Their dives are mostly to depths of 19 to 62 m (maximum of 97 to 175 m) and for 2 to 3 min (maximum of 4.4 to 7.7 min). Diving is continuous during these bouts, and time spent at the surface between successive dives is brief, around 1 min.

Lactating New Zealand (Hooker’s) sea lions (Phocarctos hookeri) also dive almost continually when at sea, averaging about 7.5 dives per hour, varying little with time of day. Dive depths average about 123 m (maximum of 474 m) and last between 4 and 6 min (maximum of 11.3 min). Most dives are evidently to the sea bed to forage on demersal and epibenthic fish, invertebrates, and cephalopods.

A few lactating Australian sea lion (Neophoca cinerea) females were reported to repeatedly forage on the sea botton (ca. 150 m deep) on the continental shelf of South Australia within 30 km of the coast.

Northern fur seals (Callorhinus ursinus) may be at sea continuously lor several months or more from autumn through spring, but their diving behavior has not been studied then. Most data come from lactating female fur seals that are foraging near rookeries in the Bering Sea in summer. Then they forage in bouts that mostly occur at night. Seals mostly make shallow dives to depths of 11 to 13 m, lasting around 1 to 1.5 min. These dives tend to be at night when seals are in pelagic habitats.

Depths and durations of dives of Galapagos fur seals (Arctocephalus galapagoensis) increase as they get older. Six-month-old seals dive to depths of around 6 m for up to 50 sec and dives occur at all hours. One-year-old seals reach depths of 47 m and durations average 2.5 min. Most of those dives occur at night. When 18 months old, seals are at sea mostly at night, diving continually for periods lasting around 3 min and reaching depths of 61 m.

Lactating Juan Fernandez fur seal (Arctocephalus philippii) females dive mostly at night to depths of 50 to 90 m, although most dives are shallower than 10 m. They last, on average, 1.7 to 2.0 min (longest 3.46 min).

Lactating female New Zealand fur seals (Arctocephalus forsteri) dive as deep as 274 m, and their longest dives have been measured at around 11 min. Median dive depths are around 5 to 10 m. They occur in bouts with the longest bouts at night. The deepest dives occur around dawn and dusk. Dives are shallowest (30 m) and shortest (1.4 min) in summer and get progressively deeper and longer through autumn (54 m, 2.4 min) and winter (74 m, 2.9 min).

Most dives of female Australian fur seals (Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus) are to the sea bed on the continental shelf at depths of 65 to 85 m. The median depth of one foraging male fur seal was 14 m and the median duration of dives was 2.5 min. The deepest and longest dives of that male were 102 m and 6.8 min, respectively, and the seal spent about one-third of its time at sea diving and foraging, with little variation in activity with time of day.

Lactating female subantarctic fur seals (Arctocephalus tropicalis) at Amsterdam Island dive predominantly at night. These foraging dives get progressively deeper and longer from summer (10 to 20 m and about 1 min long) through winter (20 to 50 m and about 1.5 min long). The deepest dive recorded is 208 m and the longest is 6.5 min.

Lactating female Antarctic fur seals (Arctocephalus gazella) dive mostly at night when they are at sea for periods of 3 to 8 days at a time in summer. These nighttime dives are shallower (about 30 m or less) than dives made during the day (40 to 75 m), closely matching the vertical distribution of krill. Maximum depths and durations of dives have been measured at 82 to 181 m and 2.8 to 10 min, respectively, for individual females. Seals apparently adjust their diving behavior to maximize the proportion of time that they spend at depth. Young pups dive mostly to depths of about 14 m, depending on their body size, for mean durations of 20 sec. Their diving abilities continue to develop during their first couple of months of life, and by the time they are weaned at around 4 months of age, they are able to dive to the same depths and for about the same amount of time as adult females.

B. Odobenids

The diving patterns of the walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) are not well studied. It is known, however, that its dives may last 20 min or more, although most may be less than 10 min and exceed 100 m. The longest dive yet recorded lasted about 25 min and the deepest was to 133 m. Most dives are likely shallower than about 80 m, as its benthic prey of mollusks are generally found in relatively shallow coastal or continental shelf habitats. Near northeast Greenland, walruses may be submerged about 81% of the time when they are at sea and are presumably diving and foraging most of that time.

C. Phocids

Phocid seals generally are at sea continually for weeks to months and appear to dive, and perhaps forage, virtually constantly.

Elephant seals are perhaps the best studied of marine mammal divers. The dives of weaned southern elephant seal pups (Mirounga leonina) are to about 100 m for about 6 min and they dive virtually continuously when at sea for several months. Heavier pups dive deeper (to ca. 130 m) and longer (ca. 7 min) than smaller pups (88 m and 5 min). Dives of juvenile southern elephant seals last around 15.5 min (maximum of 39 min) to depths averaging 416 m (deepest 1270 m) and they spend about 90% of their several months at sea diving. Intervals between dives are brief, rarely lasting more than 2 min. Adult southern elephant seal dives average 400 to 600 m and 19 to 33 min (deepest 1444 m and 113 min) and also occur continuously while they are at sea for up to 7 to 8 months.

Northern elephant seals also dive continually when at sea for several months or more with only brief periods at the surface (1 to 3 min) between dives. Dives of adults are to modal depths of 350 to 400 m and 700 to 800 m (maximum of 1567 m) and average 20 to 30 min (maximum of 77 inin). Depths and durations of dives differ between adult males and females depending on season and geographic location. Generally, these seals feed on pelagic fish and squid, although some seals may also dive to and feed near the sea floor near the coastlines of continents and islands.

Dives of Hawaiian monk seals (Monachus schauinsiandi) are between 3 and 6 min long and mostly shallow, between 10 and 40 m deep, where the seals forage near the sea bed on epibenthic fish, cephalopods, and other invertebrates. Adults may occasionally dive to greater depths of up to 550 m when foraging outside of the shallow atoll lagoons of the northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

Weddell seals (Leptonychotes weddellii) may forage for much, if not most, of the year beneath the unbroken fast ice and the more open pelagic pack ice zones of the Antarctic. Diving and foraging occur in bouts of about 40 to 50 consecutive dives over a several hour period, usually to depths of 50 to 500 m. Dives of young pups are relatively shallow and brief but get progressively deeper and longer as pups age. They plateau when the pups are weaned when about 6 to 8 weeks old. The dives of 1 year olds are somewhat shallower, to around 118 m, compared to adult females (163 m). The deepest recorded is about 750 m and the longest over 73 minutes. Dives are shallower (350 to 450 m) in spring (October to December) than in summer (January; 50 to 200 m), evidently reflecting a shift in preferred hunting depths.

Among the Antarctic pack ice seals, Ross seals (Om-matophoca rossii) are also relatively deep divers. One female that was monitored near the Antarctic Peninsula in summer dove exclusively at night, mostly to depths of 110 m (maximum of 212 m) and for about 6.4 min (longest 9.8 min). Diving was continual while the seal was in the water with about 1 min between dives. The deepest dives (175 to 200 m) occurred near twilight and the shallowest (ca. 75 to 100 m) at midnight.

In summer, crabeater seals (Lobodon carcinophaga) dive primarily at night and haul out on pack ice during the day, although some diving bouts may last up to 44 hr without interruption. Most dives are 4 to 5 min long to depths of 20 to 30 m, with maximum depths and durations of 430 m and 11 min, respectively. Dives near twilight are deepest and those near midnight shallowest.

Baikal seals (Pusa sibirica) apparently dive continually from September through May, when the freshwater Lake Baikal is frozen over, and haul out only infrequently then. Most dives are 10 to 50 m deep in the middle of Lake Baikal where the water depth is around 1000 to 1600 in. Occasionally seals descend to more than 300 m. Dives last between 2 and 6 min but some have been measured at more than 40 min.

Dives of another closely related freshwater seal, the Saimaa seal (Pusa hispida saimanensis) of Lake Saimaa in eastern Finland, last about 6 min in spring and increase to about 10 to 11 min by autumn. In summer and autumn, long series of sequential dives lasting more than 10 min each may occur over 3 hr or more. The longest dive recorded is about 23 min, when the seal may actually have been resting on the bottom rather than feeding.

Modal dive depths for breeding age, male ringed seals (P. hispida hispida) are 10 to 45 m and for subadult males and postpartum females 100 to 145 m. Durations of dives for adult males are around 4 min and around 7.5 min for adult females.

Harbor seal (Phoca vitulina) diving behaviors have been studied in a number of areas throughout their range in the North Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans. Dives in the Wadden Sea (northeast Atlantic) average from 1 to 3 min (maximum of 31 min) with little variation between night and daytime behavior. When in the water, about 85% of their time is spent diving. In the western Atlantic, foraging dives of adult males are mostly deeper than 20 m but are shallower during the mating period, when they are defending aquatic territories or searching for females to mate with instead of foraging. Dives of lac-tating females are to 12 to 40 m and occur in bouts lasting several hours, mostly during the day. In southern California, dives are as deep as 446 m. Most, however, are to modal depths of 10, 70, or 100 m with an occasional mode at around 280.

Bearded seal (Erignathus barbatus) adult females near the coast of Spitzbergen, Norway, dive mostly at night to depths of around 20 m (deepest at 288 m) and for 2 to 4 min (longest 19 min). Nursing pups may dive to around 10 m (maximum of 84 m) for about 1 min (maximum of 5.5 min). Pups spend about 40% of the time that they are in the water diving. Depths and durations of dives increase as the pups age.

Most dives of lactating female gray seals (Halichocrus grypus) are to the sea floor and last about 1.5 to 3 min (maximum of 9 min). Most foraging dives of juvenile gray seals in the Baltic Sea are to depths of 20 to 40 m.

Lactating female harp seals (Pagophilus groenlandicus) dive about 40 to 50% of the time that they are at sea. Dives average about 3 min (maximum of 13 min) to depths of up to 90 m.

Hooded seals (Cystophora cristata) repeatedly dive to depths of 1000 m or more and for 52 min or longer. Most feeding dives appear to be to depths of 100 to 600 m.

III. Cetaceans

A. Odontocetes

Limited data for odontocete cetaceans so far indicate that short-beaked common dolphins (Delphinus delphis) may forage at depths of up to 260 ni for 8 min or more, although most dives are around 90 m deep, last about 3 min, and are mostly at night. Pantropical spotted dolphins (Stenella attenuata) dive to at least 170 m; most of their dives are to 50 to 100 m for 2 to 4 min and most feeding appears to occur at night. Atlantic bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truneatus) near Grand Bahama Island off southeastern Florida often dive to the ocean bottom (7-13 m depth) and burrow into the sediment (“crater-feeding”) to catch fish dwelling or hiding there. Long-finned pilot whales (Globieephalas melas) dive to over 500 to 600 m for up to 16 min. Northern bottlenose whales (Hyperoodon ampul-latus) regularly dive to the sea bed at depths of 800 to 1500 m for more than 30 min per dive and occasionally for 2 hr.

Harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) near Japan have dived almost continuously when observed for short periods. Maximum dive depths are around 70 to 100 m, although about 70% of dives may be less than 20 m. These porpoises descend to and ascend from depth at greater rates when diving deep dian when the dives are shallow. In waters near Denmark, porpoises dive as deeply as 84 m and for up to 7 min from spring dirough late autumn.

Female white whales (Delphinapterus leucas) dive more often between 2300 and 0500 hr than during the day, although males may dive at the same rate at all hours. Dive rates and time spent at the surface decline whereas dives deepen and lengthen from early through late autumn. Most dives are deep (400 to 700 m), with the deepest recorded at 872 m, and last about 13 min on average (maximum of 23 minutes). Dive duration increases with body size.

Narwhals (Monodon monoceros) regularly dive to more than 500 m and occasionally deeper than 1000 m, but most dives are to depths of 8 to 52 m and last less than 5 min, although as long as 20 min on occasion. The rate of diving varies between adult males and females. When diving shallow, narwhals descend and ascend relatively slowly (<0.05 m/sec) compared with deeper, longer dives (1 to 2 m/sec) where substantially more time is spent at maximum depth.

Killer whales (Orcinus orca) along the northern coast of North Island, New Zealand, dive to the ocean bottom (ca. 12 m depth or less) after stingrays and perhaps burrow into die sediment to catch them.

Sperm whales (Physeter niacrocephalus) dive to depths of up to 2000 m for 60 min or more. Near Kaikoura, New Zealand, the average duration of dives is about 41 min with about 9 min spent at the surface between dives. Both durations and surface intervals are longer in summer than in winter. Males spend little time at the surface compared to females. Average dive durations have been measured at 36 min near Sri Lanka and about 55 min near the Azores. Sperm whales in the Caribbean were reported to make dives averaging 22 to 32 min during the day (longest 79 min) and 32 to 39 min at night (longest 63 min).

B. Mysticetes

As yet there is no evidence for a taxonomic relationship between body size and maximum dive depths for mysticete cetaceans, although preliminary correlations have been reported between maximum dive durations and body size.

While in shallow coastal lagoons during the spring breeding season, gray whales (Eschrichtius robustus) dive for about 1 to 5 min (maximum of 28 min) to average depths of 4 to 10 m (maximum recorded of 20.7 m). It is not clear what the function of these dives may be other than perhaps subsurface resting, as breeding whales are presumed to fast. In the Bering Sea in summer, when whales are feeding, dives average about 3 min.

Fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in the Ligurian Sea dive repeatedly to depths around 180 m (maximum 474 m) for around 10 min (longest 20 min) while they prey on deep-dwelling krill. Elsewhere, fin whale dives have been reported to last about 5 min near Iceland and about 3 min in the North Atlantic and near Long Island, New York, in summer.

When chased by commercial whalers, dives of blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) lasted up to 50 min. Blue whales off central and southern California otherwise spend about 94% of their time submerged. Dives lasting longer than 1 min are 4.2 to 7.2 min, on average (longest 18 min), and to around 105 ni (deepest 150 to 200 m). Dives of pygmy blue whales (B. m, brevicauda) have been measured to average 9.9 min (longest 26.9 min).

Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Frederick Sound, Alaska, make rather brief (most less than 3 min) and shallow (60 m or less) dives, although some may exceed 120 m on occasion.

When on summer feeding grounds in the Beaufort sea, dives of bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) last 3.4 to 12.1 min and some are to the relatively shallow sea bed. Dives of calves are very short compared to adults and they also spend more time at the surface between dives. Most dives of juveniles last about 1 min (longest 52 min) to depths of around 20 min. Longer dives, up to 80 min, have been observed for bowhead whales that were harpooned and being chased by whalers. Dives lasting longer than 1 min (“sounding dives”) average between 7 and 14 min. Dives made while whales are migrating through heavy pack ice are deeper and longer than those made while in open water. Lactating females dive less often and for shorter periods than other adult whales.

Dives of North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) near Cape Cod, Massachusetts, last around 2.1 min.

IV. Other Marine Mammals

Manatees (Trichechus manatus, T. inunguis, and T. sene-galensis) feed on floating and submerged vegetation in shallow nearshore habitats so it is unlikely that their dives often exceed 25 to 30 m. Direct observations of free-ranging animals have shown that most dives are less than 5 min, although a few have been timed at more than 20 min. These longer dives may have periods of rest at the bottom rather than feeding activity. Dugongs (Dugong dugon) also feed on submerged vegetation, most often in coastal and offshore seagrass beds either on the sea bottom to depths of 20 m or in surface canopies. The longest foraging dives observed are around 6 min, but most have been reported to last only between 2 and 4 min.

Sea otters dive and forage mostly in shallow nearshore waters. Dives may be in bouts lasting several hours during the day and night, interrupted by periods at the surface to groom, process food, or rest. Juvenile males often dive in deeper water, for longer periods, and further from shore than juvenile and adult females. Details on diving sequences, depths, durations, and other parameters are just beginning to emerge Irom the recent deployment of TDRs in southeast Alaska and in the Gulf of Alaska.

Polar bears (Ursns maritlmus) are powerful swimmers and probably make some dives while moving among ice floes, the fast-ice edge, or coastlines, but nothing is known of the details of such diving performance. They prey mostly on ringed seals and whale carcasses on the surface of the ice or along shorelines and also on white whales and narwhals that they may attack and kill at the sea surface and then drag out of the water to consume.