I. Characters and Taxonomic Relationships

Bryde’s whales were long confused with sei whales (Balacnoptera borealis) because of morphological similarities; this confusion lasted into the 1970s. Bryde’s whales were first described by Anderson (1878) based on examination of a stranded balaenopterid on Thavbyoo Creek beach, Gulf of Marataban, Burma. He gave it the scientific name Balaenoptera edeni in honor of the British high commissioner in Burma, Sir Ashley Eden. Olsen (1913) found another new species among “sei whales” caught in Durban, South Africa, and gave it the scientific name B. brydei in honor of his sponsor Johan Bryde, a pioneer in South African whaling from the traditional whaling port of Sandefjord. Junge (1950) concluded that the two names were synonymous based on examination of a skeleton collected in Pulu Sugi, Singapore. Further studies by Omura (1959) and Best (1960) supported Junge’s view, and their conclusion had been generally accepted until recently, with B. edeni having priority as the scientific name. (The common name remained “Bryde’s whale” probably due to its wide popularity.) However, today it is not clear how many species of Bryde’s whale-like baleen whales there are or what their scientific names should be (Rice, 1998). Wada and Numachi (1991) found that a small form occurring off the Solomon Islands and Java did not accord with other Biyde’s whales in allozymes. These results suggesting the existence of two species were supported by mtDNA analyses reported by Yoshida and Kato (1999). Rice (1998) proposed provisional recognition of the existence of two species, with the nomenclature unsettled. The problem is that it is not yet known to which of the two species the holotype specimen of B. edeni (in Calcutta) belongs. It is not distinctive morphologically (at the upper end of the size range for the small form, but still physically immature) and comes from an area of overlap of the two species. If genetic analysis determines that it belongs to the small species, then the small species will bear the name B. edeni. If it proves to be of the large species, then that species will bear the name, B. brtjdei will fall into synonymy, and a new name (and holotype specimen) will be needed for the small species.

Bryde’s whales are medium-sized balaenopterids. Females are larger than males throughout life, by about 2 feet (0.50.6 m) at full maturity. It is believed they reach 15.5 m, but most are much smaller. As demonstrated by Best (1977) for South African Bryde’s whales (Table I) animals from coastal stocks or stocks inhabiting rather areas are generally smaller than those from migratory pelagic stocks. Southern Hemisphere animals are also larger than Northern Hemisphere animals. In the South Africa and western North Pacific stocks, body length increases rapidly until 4-5 years, reaches about 90% of asymptotic length for both sexes at about 10 years, and ceases to increase at about 20-25 years (Best, 1977). The length-weight relationship is given by the equation (Ohsumi, 1980):

where W is body weight in metric tons and L is body length in meters.

If mean lengths at physical maturity in the western North Pacific stock are substituted into the equation, weight estimates are 15.0 (at 13.0 m) and 16.6 (at 13.5 m) tons for males and females, respectively.

Bryde’s whales closely resemble sei whales but have a number of distinctive characteristics (Fig. 1). Body color is principally dark smoky gray above and white below, but the dark area extends down to include the throat grooves and the flippers. The boundary between dark and light areas is diffuse. The rostrum is V shaped as in other balaenopterids (Fig. 1). The head occupies about 24-26% of the body. The dorsal fin is extremely falcate with a tapering tip and is located at 25.2-26.6% of body length anterior to the flukes. The flukes are broad (23.5-24.4% of body length), with rather straight posterior margins.

TABLE I

Distinguishing Characteristics of the Two Forms of Bryde’s Whales off Donkergat”

|

Characteristic |

Inshore form |

Offshore form |

|

Distribution |

<20 miles off the coast |

>50 miles off the coast |

|

External appearance |

Very few oval scars, several with scrapes under tail |

Numerous oval scars, no scrapes under tail |

|

Baleen shape (length: |

2.22-2.43 |

1.83-2.24 |

|

breadth quotient) |

||

|

Food |

Anchovies, pilchards, maasbankers |

Euphausiids, myctophids, Lestidium |

|

Size at sexual |

Males 3£M0 ft. |

Males 42-43 ft. |

|

maturity |

Females 41 ft. |

Females 41^2 ft. |

|

Breeding season |

Unrestricted |

Principally autumn |

|

Mean number of |

3.75 |

1.00 |

|

ovulations per |

||

|

reproductive cycle |

||

|

Calculated ovulation |

2.35 |

0.42 |

|

rate |

||

|

Size at physcial |

Males 43 ft. |

Males 45 ft. |

|

maturity (= L°°) |

Females 45 ft. |

Females 47^7 ft. |

Figure 1 (Top) Bryde’s whale in western North Pacific in summer 1993 (photograph by Tomio Miyashita): (Bottom) head region has a lateral ridge on the rostrum of an animal off South Africa .

Pelagic Bryde’s whales, such as those in the western North Pacific stock or the offshore form off South Africa, bear large numbers of oval pit-like scars from bites by the tropical cookie cutter shark (Isistius sp.), evidence of migration to tropical waters. This scarring is usually most extensive on the lateral side of the peduncle, leading to an appearance like that of galvanized iron. Such scarring is rare on animals of the coastal form off South Africa; this may also be true for coastal animals in neritic waters off Kochi, southwest Japan, indicating the whales do not migrate to tropical waters. Best (1977) further noted that the coastal form has thin scratches on the undersurface of the tail and ventral keel and suggested that these scratches are due to accidental touching of the sea bottom in shallow waters.

The throat grooves extend to or beyond the navel, whereas those of the sei whale do not reach the navel. The number of grooves between the flippers is 54-56.

The most distinctive external character allowing the discrimination of Bryde’s whales from other baleen whales is the presence of three prominent ridges on the rostrum (Fig. 1). The ridges run from just behind the tip of the snout to anterior to the blowholes and are composed of one central ridge and two lateral subridges.

Bryde’s whales have 285-350 dark slate-gray baleen plates on each side of the mouth. They are much broader and have coarser bristles than those of sei whales. The longest plate may reach 40 cm in length above the gum. Best (1960, 1977) reported a clear difference in the proportion of length to breadth of the plates in South Africa, with those of the inshore form being more slender than those of the offshore form. Kawamura (1978) found animals in the South Pacific to have finer bristles than those in the western North Pacific stock, probably reflecting a difference in their feeding habits.

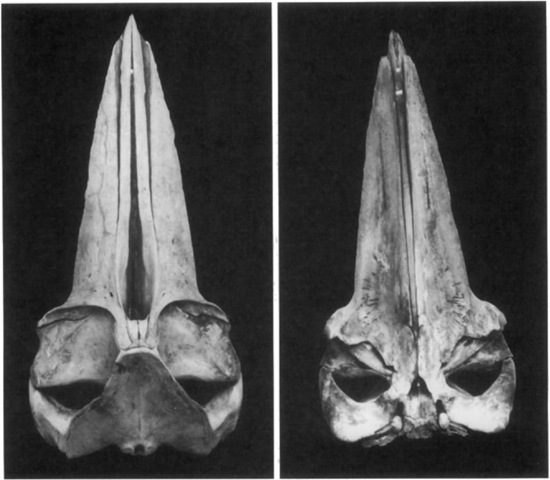

The skull occupies about 24.1-25.8% of total body length. It is relatively broad, short, and flat for a balaenopterid skull (Fig. 2). The rostrum is also relatively short and pointed. Its sides are nearly parallel posteriorly but slightly convexly curved anteriorly. The curved and robust mandible is also conspicuous among bal-aenopterids. The vertebrae formula is C 7 + D 13 + L 13 + Ca 21 – 22 = 54-55 (Omura et al, 1981), for a total slightly lower total count than in sei whales (56-57). Cervical vertebrae are un-fused, and thoracic (dorsal) vertebrae have short neural processes. The ribs are relatively thin and broad and usually number 13-14. The first rib has a double head, a characteristic shared with the sei whale. The phalangeal formula is I (6), II (5), IV (5), V (3).

II. Distribution, Stocks, and Ecology

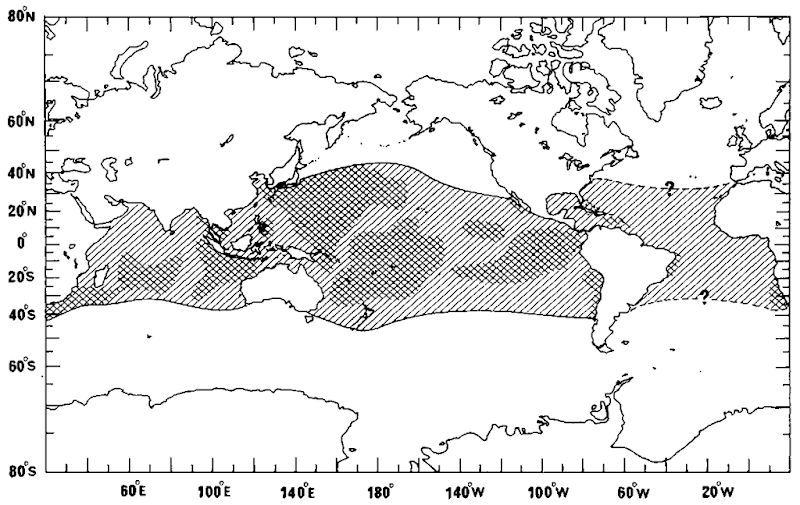

Although there is a general pattern of migration toward the equator in winter and to higher latitudes in summer, Bryde’s whales are seen throughout tropical and warm temperate waters of 16.3°C or warmer year round. Their occurrence has been reported from all tropical and temperate waters in the North and South Pacific, Indian Ocean, and South and North Atlantic between 40°N and 40°S (Fig. 3).

In the western North Pacific, Bryde’s whales occur in temperate and tropical waters off the Pacific coasts of Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines to 150°W, with the northern limit corresponding approximately to the southern margin of the sub-Arctic boundary at about 40°N and the southern limit at about 2°S. This is the western North Pacific stock, with abundance estimated at about 24,000 (CV = 0.20; IWC, 1997). Bryde’s whales inhabit the east China Sea; this stock extends to the coastal waters of the Pacific side of southwest Japan but is restricted to the west of the Kuroshio warm current (Kato et al, 1996). In the Philippines, Bryde’s whales are significantly smaller than those of the western North Pacific stock. They are distributed from there to the Gulf of Thailand, Burma, New Guinea, and die Solomon Islands, all likely “small or dwarf forms” considered to constitute a different species. Bryde’s whales also occur in eastern tropical Pacific waters mainly west of 150°W between 20°N and 10°S; abundance is estimated at 13,000 (CV = 0.202; Wade and Ger-rodette, 1993). Biyde’s whales also inhabit the Gulf of California throughout the year; these are assumed to constitute an independent stock. They are also widely seen in the south, occurring continuously from the east coast of Australia to 120°W in a zone between the equator and about 30°S, including northern New Zealand. In the eastern South Pacific, the species is distributed in coastal waters off South America from the equator to 37°S. Occurrence seems to be related somewhat to seasonal upwelling events. Little is known about stock structure in these areas, but it is expected that the coastal stock(s) is genetically different from those of the western South Pacific.

Figure 2 Dorsal and ventral views of a skull of Bryde’s whale caught in the western North Pacific and landed at Bonin Island in July 1983.

Bryde’s whales are common throughout the Indian Ocean, from waters north of 40°S such as the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea. Geographical concentrations occur south of Java to the west coast of Australia (east of 90°E), in the central Indian Ocean (65-90°E), off Madagascar (35-65°E), and off South Africa (east of 35°E). Stock structure in these areas has not been fully examined other than to confirm the existence of inshore and offshore forms off South Africa (see later). However, it would not be realistic to assume that one homogeneous stock is distributed over the Indian Ocean.

Two allopatric forms of Bryde’s whale known as the inshore and offshore forms are found off the west coast of South Africa (Best, 1977). The inshore form is restricted to within 20 miles from the coast and is seen there throughout the year. The offshore form occurs in waters over 50 miles from the coast and migrates north to the equator in winter. Accurate estimates of population abundance are not available for either stocks. Little is known about distribution and stock structure in the rest of the Atlantic, especially in the Northern Hemisphere. However, Bryde’s whales have been sighted or stranded from Morocco south to the Cape of Good Hope in the east and from Virginia south to Brazil in the west, including the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean, and off Venezuela.

Figure 3 Worldwide distribution of Bryde’s whales based on published or available information. Dense hatch represents areas in which higher densities arc expected.

Bryde’s whales feed mainly on pelagic schooling fishes such as pilchard, anchovy, sardine, mackerel, herring, and others. However, they also feed on small crustaceans such as euphausids and copepods and on cephalopods and pelagic red crabs (Pleu-roncodes) (Nemoto and Kawamura, 1977; Best, 1960, 1977; Kawainura, 1980; Ohsuini, 1977a). They are considered opportunistic feeders, unlike sei whales, which concentrated on cope-pods. Off South Africa, they tend to be dependent on eu-phausiids in pelagic waters and feed on schooling fishes in coastal waters; thus feeding habits may be characteristic of stocks (Best, 1977). Balaenopterids consume about 4% of body weight daily at the peak of the feeding season; this corresponds to approximately 600-660 kg per day for a Bryde’s whale.

Bryde’s whales are sometime seen within high-density patches of bonito (Sarda) in pelagic waters in the North Pacific. This may be a result of two predators chasing the same prey. Similarly, off the coasts of Kochi and Kasasa, southwest Japan, it is very common to see Brvde’s whales feeding in patches of sardines or juvenile tuna, especially in summer. They have also been observed to utilize bubble net foraging with slow circle swimming under the surface.

III. Behavior and Life History

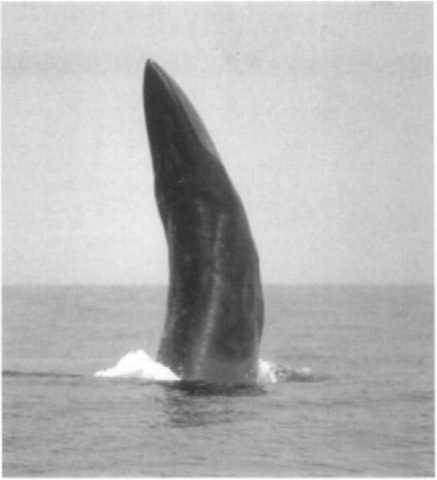

Bryde’s whales do not gather into large groups. They are usually seen singly or in groups of 2-3 in the North Pacific, with a maximum group size of 12. They usually surface steeply like other balaenopterids. The blow is 3-4 m high. The dorsal fin is seen after the blow and then sometimes the dorsal keel. They seldom fluke up before diving. It is generally believed that they usually move at 2-7 km/hr, but can swim as fast as 20-25 krn/hr and dive up to 300 m. Bryde’s whales breach more often than other balaenopterids (Fig. 4). Biyde’s whales produce powerful low-frequency moaning sounds averaging 0.4 sec in duration (range, 0.2-1.5 sec) with most of the energy concentrated at 124-250 Hz and a frequency modulation of as much as 15 Hz (Cummings, 1985).

While Biyde’s whales have a life history similar to that of other balaenopterids, there are species-specific aspects due to their remaining in tropical and temperate waters throughout the year. As for many other migratory large cetaceans, little is known about the breeding grounds, even for inshore or coastal stocks, although it is generally believed that they must be somewhere in lower latitudes from the migratory stocks. In waters off Kochi (east China Sea stock), females accompanied by small calves sometimes appear in early spring, but there is no evidence that they give birth there. In pelagic stocks, peaks of both conception and calving are in winter, although these are much more diffuse than in other migratory balaenopterids. Best (1977) reported that breeding is not seasonally restricted for inshore animals off South Africa; this may be true for other local stocks.

Gestation lasts for about 11 months. Length at birth is about 4 m. The sex ratio at birth is not different from parity (Best, 1977). Lactation lasts about 6 months and calves wean at about 7 m in body length. Males attain sexual maturity at 11-11.4 m and females at 11.6-11.8 m in the western North Pacific stock. Taking into account bias due to operations and regulation of whaling, Best (1977) found length at sexual maturity for the inshore form to be less than for the offshore form off South Africa, by 1 foot in females and 3 feet in males. The mean age at sexual maturity is slightly less than 7 years. Based on the annual ovulation rate (0.42-0.46; Best, 1977; Ohsumi. 1977b) for pelagic Bryde’s whale stocks, the calving interval is about 2 years. Inshore waters off South Africa are very frequent ovula-tors (1.88 per year), but this does indicate a higher pregnancy-rate but rather probably results from the extended breeding season. In summary. Bryde’s whales have a 2-year reproductive cycle composed of 11-12 months gestation, 6 months of lactation, and 6 months resting.

Figure 4 Breaching of a Bryde’s whale off Kochi, Japan.

IV. Conservation Status

Bryde’s whales were not harvested commercially or substantially until recent times; their value became relatively important in the late 1970s with the shift of whaling to the smaller species. However, commercial harvest of this species has been prohibited by a moratorium imposed by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) in 1987.

Because Bryde’s whales had been mainly exploited after substantial improvement of IWC stock management procedures adopted in 1975 (the MNP or new management procedure), stocks have kept relatively stable. A reliable estimate of the population trend for North Pacific Bryde’s whales has been available for the western North Pacific stock from a comprehensive assessment conducted by the IWC in 1995 and 1996. According to the assessment (IWC, 1997), the population has been increasing since 1987, and the current population level (mature females in 1996 relative 1911) ranges from 56.7 to 81.4%.