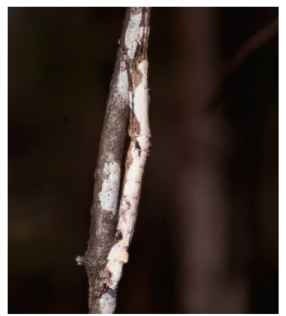

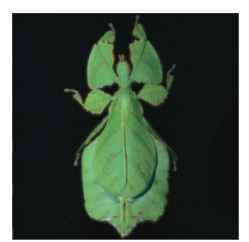

Phasmida are nocturnal exopterygote insects. They exhibit a variety of unpredictable and bizarre shapes. Some look like twigs or tree bark (Figs. 1 and 2) and may seem to be covered by lichens or moss. Others are indistinguishable from living or dead leaves (Fig. 3), mimicking even leaf veins and mildew spots to perfection. Phasmida are large, and a few are remarkable for their gigantic size. The longest insect species in the world is Phobaeticus kirbyi from Borneo, with one documented female measuring 55 cm in length.

FIGURE 1 A female of Oxyartes spinosissimus, a lichen mimic.

FIGURE 2 A male and female of Aplopus sp. in the act of mating. The smaller male is hanging off the back of the female.

FIGURE 3 A female of the walking leaf Phyllium bioculatum.

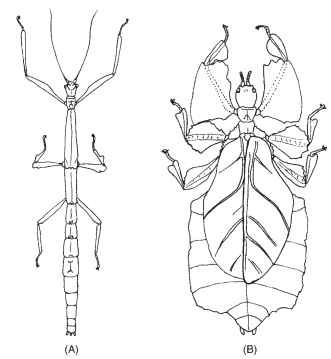

FIGURE 4 Female Euphasmida: (A) Phenacephorus auriculatus and (B) P. bioculatum.

Phasmida inhabit tropical, subtropical, and temperate forests, savannas, grasslands, and chaparral; their diversity is highest in the tropics.

PHYLOGENY AND CLASSIFICATION

Over 3000 species of Phasmida have been described. The genus Timema from the western United States is considered to be sister group to the remainder of the order, which is referred to as the Euphasmida. Timema are small, wingless, and cryptically colored. Euphasmida are larger, winged or wingless, usually possessing an elongated mesothorax, and are stereotyped as stick or leaf insects (Fig. 4 ). Timema have no fossil record. The oldest Euphasmida fossils date to the middle Eocene, 44—49 mya. Oligocene and Miocene fossils are known from Florissant shale, Baltic, and Dominican Republic amber.

The taxonomy of the order is problematic. No workable classification scheme exists, and those that are available are not based on phylogenetic relationships. Assignment to a category such as family, tribe, even suborder provides so little information that it is almost meaningless. This is in contrast other insect orders, such as Coleoptera, where a suborder, or family-level identification, say, provides a wealth of biological information about the specimen. In spite of the lack of an acceptable classification, the fauna of a few areas (e.g., Europe, Malaysia, Borneo, Japan, United States, Canada, New Zealand) have been sufficiently studied to permit tentative identification of species by nonspecialists.

BIOLOGY

Sexual dimorphism is extreme in the Phasmida, and it is difficult to associate the sexes unless mating adults are found under natural conditions, or if males and females are obtained from the rearing of eggs in captivity. Reproduction is usually sexual, but many species are parthenogenetic. Eggs resemble plant seeds, are laid singly, and are either dropped, flicked, buried, glued to a surface, or riveted to a leaf. Some species rely on ants to disperse them. After successive molts, nymphs regenerate limbs lost by autotomy (the purposeful shedding of appendages). The entire life cycle takes from several months to several years depending on the species. Phasmida feed primarily on flowering plants, but a few eat either gymnosperms or ferns. The primary defense against predation is crypsis. Secondary defenses can include catalepsy (e.g., death feigning), startle displays, or the ejection of an irritating spray fired from a pair of prothoracic exocrine glands.