The Dermaptera (earwigs) comprise a small, relatively old, hemimetabolous order of insects characterized in their external anatomy by paired cerci (forceps) at the posterior end, and (in winged forms) short tegmina incompletely covering hind wings that are also unique structurally (Figs. 1 and 3 ). Behaviorally, earwigs are thigmotactic, nocturnal, and subsocial, in a system whereby the female parent broods, grooms, and defends eggs and young nymphs (Fig. 2). Internal anatomy is typical of orthopteroids, except that the corpora allata have undergone fusion to a single median structure, and the paired ovaries are primitively polytrophic (i.e., each follicle contains an oocyte and a single nurse cell).

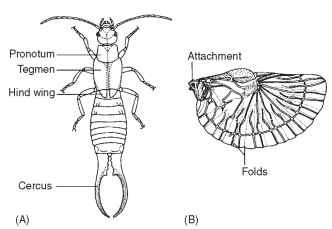

FIGURE 1 European earwig (Forficula auricularia): (A) adult male and (B) his right hind wing. [Reprinted with the permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, from College Entomology by E. O. Essig

FIGURE 2 Female ring-legged earwig (Euborellia annulipes), brooding over her clutch of eggs.

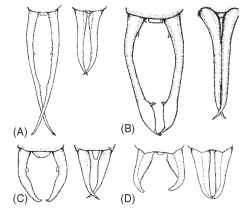

FIGURE 3 Sexual dimorphism in cerci of four species of dermaptera (males on left and females on right): (A) Metrasura ruficeps (Family Forficulidae); (B) Ancistrogaster scabilosa (Family Forficulidae); (C) Paralabella dorsalis (Family Labiidae); (D) Anisolabis maritima (Family Anisolabidae).

Earwigs are members of the orthopteroid assemblage and have a strong sister-group relationship with the Dictyoptera; they also may be closely related to the Grylloblattodea. Four suborders are generally

FIGURE 4 Male Euborellia annulipes (Family Anisolabidae) scavenging for aphids and pollen in a flower head (Scaevola sp.).

recognized, and of the three extant ones, the Hemimerina and Arixinina are small groups of viviparous ectoparasites of vertebrates; most species of earwigs are oviparous members of the third group, the Forficulina. Earwigs are not of medical importance; they do not crawl in people’s ears (occasional anecdotal accounts notwithstanding), and they do not bite, although some may pinch with their forcepslike cerci. Some earwigs may be pests of gardens or households; alternatively, some species are important biocontrol agents, feeding on agricultural pests, such as aphids, armyworms, mites, and scale insects (Fig. 4) .

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

In 1773, DeGeer coined the term Dermaptera (but used the name for all orthopteroids). Kirby in 1815 introduced the name in its current sense, as a small insect order of about 2000 described species. The oldest known examples of dermapterans are Jurassic fossils dating from about 208 mya. These elongate, slender, hemimetabolous (incompletely metamorphic) insects have chewing mouthparts, three-segmented tarsi (in extant groups), (usually) compound eyes, and no ocelli. The presence of abdominal cerci makes them easy to distinguish from beetles. The cerci are typically forcepslike (though they are filiform in at least some parasitic forms) and are sexually dimorphic (Figs. 1 and 3). The forceps are used for a variety of purposes, including prey capture, defense, fighting, and as aids in copulation and in folding of hind wings. Earwigs are diploid (i.e., they have a double set of chromosomes); males are heterogametic (i.e., they produce gametes with different sex chromosomes, e.g., X and Y).

Some earwig species are wingless as adults, but most have short front wings (tegmina) that do not cover the abdomen. The derivation of the name “dermaptera” (derma, skin; ptera, wing) refers to the thickened or “skinlike” front wings. The hind wings are unlike those of any other group of insects: they are semicircular and membranous, with radially arranged veins. They fold fanlike beneath the front pair when the insects are at rest (Fig. 1). The derivation of the common name (earwig) may be a corruption of “earwing,” in reference to the hind wing resemblance to a human ear. Alternatively, it could be a reference to the ancient Anglo-Saxon legend that these insects crawl in ears of sleeping humans. Additionally, the forceps of some species look like instruments once used for piercing women’s ears for earrings.

Earwigs typically display parental care of offspring (although there are almost no observations of maternal care in the viviparous, ectopar-asitic forms). Eggs are typically deposited in soil (or protected whorls of monocotyledonous plants); the females “roost” on the eggs until the young hatch and then they care for them (Fig. 2). The period of maternal care appears to be a time of nonfeeding of the brooding female; physiologically, her levels of both juvenile hormone and ecdysteroids (see later) are likely low during the period of egg care.

INTERNAL ANATOMY

The major elements of the neuroendocrine system are the brain, the subesophageal ganglion, three thoracic ganglia, and six abdominal ganglia (with thick, paired connectives between the ventral ganglia). Paired neurohemal corpora cardiaca are connected to the brain and frontal ganglion by strong nervous connections; the closely associated single median corpus allatum produces and releases juvenile hormone III and is in close proximity to the neurohemal dorsal aorta. The digestive system contains the typical regions of fore-, mid-, and hindgut (though gastric caecae are lacking); the midgut-hindgut junction is characterized by the presence of numerous long, slender (excretory) Malpighian tubules.

The female reproductive system consists of paired ovaries, lateral oviducts, a median oviduct, spermatheca (for sperm storage), and genital chamber. Earwigs are unusual in that the female genital opening (gonopore) is just behind the seventh abdominal segment. The ovaries are primitively polytrophic; in some species the long ovarioles branch off the lateral oviduct, while in others, short ovarioles appear in series around the oviduct. The viviparous species are pseudopla-cental, with egg maturation and embryonic development taking place in the greatly enlarged vitellarium. The male reproductive system is complex, with paired testes, paired vasa deferentia, paired or single vesicula seminalis (for sperm storage), and a paired or single common ejaculatory duct ending in the sclerotized virga (penislike structure).

RELATIONSHIPS TO OTHER INSECTS

Earwigs are members of the informal orthopteroid assemblage and share a sister-group relationship with the dictyopterans (cockroaches). The Grylloblattodea (rock crawlers) may be linked to the Dictyoptera/Dermaptera. Alternatively, earwigs may be closer to the Grylloblattodea than to any other orthopteroid order.

PHYLOGENY AND DISTRIBUTION

OF DERMAPTERA

Early in the 20th century, Burr established suborders of the Dermaptera recognized by most contemporary systematists. The four suborders (three of them recent) are as follows:

1. Archidermaptera, represented by 10 fossil specimens from the Jurassic; they are characterized by unsegmented cerci and tarsi having four or five segments.

2. Forficulina, the suborder containing most earwigs (i.e., 1800 described species, in 180 genera); cerci are unsegmented (except in a few primitive larvae) and forcepslike. This is the only suborder that occurs in North America, wherein six families are represented: Forficulidae, Chelosochidae, Pygidicranidae, Labiduridae, Anisolabidae, and Labiidae. Despite the recent application of modern techniques of molecular biology, no consensus has been reached about the phylogenetic relationships between these families.

3. Hemimerina, composed of 10 species in 1 genus (family Hemimeridae); they have filiform (segmented) cerci, and are wingless, blind, viviparous (pseudoplacental) ectoparasites of African rats.

4. Arixenina, composed of five species in two genera (family Arixeniidae); like the Hemimerina, they are viviparous (pseudo-placental), wingless, blind, and ectoparasitic of vertebrates. The Arixenina live on bats in Malayan-Philippine region; this group may be a sister group of the Labiidae.

The current geographical distribution of most families of earwigs was largely determined by continental drift, with two main centers of radiation before the Triassic opening of the Pacific Ocean being the equatorial region of the eastern Pacific (Pygidicranidae, Anisolabidae, Arixeniidae, and Labiidae) and the Afro-Indian cir-cumtropical center (Labiduridae, Chelosochidae, and Forficulidae).

The distribution has also been largely affected by climatic conditions: earwigs were “discouraged” from spreading northward from the tropics by mountain ranges of southern Europe and Asia; only more specialized members have become established in the Palearctic region (and none have been reported in the polar regions). Although most earwigs have wings, they seldom fly. The cosmopolitan distribution of some species can be attributed to their habit of hiding in crevices, especially in timber or other material that is transported by commerce.

NATURAL HISTORIES AND BIOTIC ASSOCIATIONS

Development

In oviparous species such as European earwig, Forficula auricu-laria, and ring-legged earwig, Euborellia annulipes, clutches of ovoid, creamy white eggs are laid in protected burrows; eggs can be up to 2 mm in length in larger species. Nymphs generally resemble adults but can be distinguished from them by lighter color, shorter antennae, a male-type 10-segmented abdomen (rather than the 8-segmented abdomen of the adult female), and typically female-type forceps. Sexes are not easily distinguished externally in nymphs.

Habits

Most earwigs are thigmotactic and nocturnal, inhabiting crevices of various types, bark, fallen logs, and debris. Cavernicolous (cave-dwelling) blind species have been reported in the Hawaiian Islands and in South Africa. Food typically consists of a wide array of living and dead plant and animal matter. Some earwigs have scent glands opening onto the dorsal side of the third and fourth abdominal segments, and from these they can squirt a foul-smelling yellowish-brown fluid some 10 cm or so, presumably for protection.

Reproductive Strategies

Among the Forficulina, reproductive strategies range from oviparous iteroparity (many clutches, the likely ancestral condition) to semelparity (one clutch, a trait derived in colder climates). In contrast, the Hemimeridae are viviparous ectoparasites, residing in the fur of central African rats of the genera Cricetomys and Beamys, and dining on the skin and body secretions of the host, while the viviparous Arixenina are ectoparasites of bats.

Natural Enemies

Some beetles, toads, snakes, birds, and bats have been reported as predators of earwigs. F. auricularia can be parasitized by gregarines (sporozoans, which may be harmless) in the gut, as well as nematodes, cestodes, mites, and tachinid flies (a potential biocontrol agent). A fungal parasite has also been associated with several earwig species.

MEDICAL AND ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE

Earwigs are harmless to humans: they carry no known pathogens of humans, and their mouthparts are incapable of biting humans (although some species can pinch).

Some genera (e.g., Forficula, Labidura, Euborellia) are repeatedly reported as a pest of homes, gardens, and orchards (Fig. 4). Their thigmotactic nature, coupled with (known and suspected) aggregation pheromones, can lead to high densities of earwigs in and around homes. In gardens, earwigs may attack seedlings and soft fruit. Management in backyard gardens can be accomplished by persistent trapping in bamboo tubes, rolled-up newspaper, or low-sided cans filled with vegetable oil. Removing refuge sites, such as ivy and piles of leaves, is also helpful.

Some species are also of importance to commercial agriculture, being pests of ginger, maize, and of honey bee colonies. However, earwigs are also regarded as valuable biocontrol agents for crop pests, consuming armyworms, aphids (of various types), mites, scale insects, sugarcane rootstock borers, and tropical corn borers. Several dermapteran species are found in commercial egg houses and have potential as biocontrol agents for fly eggs and larvae.