INTRODUCTION

Virtual organization has been well documented as both a tool for organizations to seek further profitability through the removal of traditional barriers as well as a method to extend the provision of services to clientele in a manner previously achievable by only large, multinational corporations (Markus, 2000). The widespread implementation of information technology and its many applications in modern business have moved the act of management toward a virtual focus, where managers are able to complete tasks through the use of teams in varying physical locations, with members that may or may not be employees of that firm, sharing a wide variety of data and information. With so many companies now employing virtual organization techniques, referring to a company as “virtual” or to its components as possessing “virtuality” lacks the clarity and specificity needed when using these firms as examples for others. The variety of methods through which a firm can achieve virtuality represents a span nearly as wide as the business community itself.

BACKGROUND

The earliest definitions of a virtual organization appeared when the concept of virtuality was applied to studies of management before information technology existed in a refined state to support the theory. Giuliano (1982) saw that with the addition of telecommunications and networking technology, there was little need for work teams to assemble at the same time or even a contiguous location. A structured concept of virtual organization was formed by Abbe Mowshowitz (1994, 2002). He defined a virtual organization in previous work as a group of employees communicating and being managed electronically through metamanagement. This concept defines the way in which a virtual task is managed and further categorizes a virtual organization as a series of virtual tasks completed by virtual teams in strategic global locations. As each team has a certain commitment to the parent organization, the similarity in purpose and communication style allows for clear distribution of work across multiple groups of organizational members.

As with Net-enabled organizations, the concept of virtual organizations has gained prominence among re- searchers and practitioners. As shown by the recent work of Schultze and Orlikowski (2001), virtuality can be understood through the perception of time and space. This paper extends the scope of the virtual organization in terms of virtual space, a metaphor used in time and space (beyond the constraints of the actual location we belong to) dimensions (Allcorn, 1997). As opposed to the virtual organization, time and space dimensions are constrained in traditional or “real” organizations. Time constraints occur in real organizations due to the operational time dimension of such organizations, while the space dimension occurs due to constraints of location.

It is true that a virtual organization inherits the attributes of virtual dimensions—a newly defined concept of time and space. In other words, a virtual organization does not exist in our time and space, but rather exists only in virtual space (perceptual world), which is only a metaphor of our consciousness and not reality. A virtual organization, in this sense, is the metaphor of our designed and structured consciousness that exists in virtual space to perform the intended actions of interest. However, the most important thing in a virtual organization is to identify the role of human actors who get involved in both the physical and the perceptual world. We attempt to explain the relationships between the human actors, the real and virtual organizations, and our perceptions of these concepts.

DUALITY OF HUMAN IDENTITIES

Metaphors play a very powerful role in structuring virtual organizations because terms like virtual space and virtual organization originate from symbolic languages (Faucheux, 1997). These metaphors provide the meaning of existence, thus we can treat the organization like a real organization in virtual space. Continuous analogical processes between virtual and real organizations explain the existence of virtual organizations because there exist similarities and discrepancies in them (Ahuja & Carley, 1999). A virtual organization, operating within virtual-space imagery, exists in our consciousness while an actual organization physically exists in various forms (more tangible or definable manner) such as culture, politics, resources, and so forth (Morgan, 1986). Although a virtual organization exists in our consciousness,it is associated with its physical counterpart in the real world. Allcorn (1997) described this counterpart as a parallel virtual organization and bureaucratic, hierarchical organization counterpart. However, there is a possibility that in the near future, a real organization will exist only when its virtual counterpart exists in virtual space. Mowshowitz (1994, 2002) described this as “a dominant paradigm” of virtual organization due to its unique advantages in the efficiency, cost, and effectiveness of goal-oriented activity. Surprisingly, human actors manage to control these two opposing ideas of real and virtual worlds; thus, it becomes obvious that humans possess duality of existence in both the real and the virtual world.

This paper discloses the social aspects of a virtual organization and identifies the role of human actors in a virtual organization (or consciousness in Faucheux, 1997). This consciousness exists in the perceptual world that we create beyond the limits of time and space (Allcorn, 1997). However, its counterparts exist in various forms (entities) in the real world. To bridge the gaps between the consciousness and the entities, there exists a need for human interveners who possess dual identities in both virtual and real worlds. This research provides the meaning of virtual organization, and proceeds to explain the relationship between the consciousness (virtual organizations) and entities (real organizations) with human intervention (human players).

Schultze and Orlikowski (2001) examine rhetorical oppositions between real organizations and virtual organizations, and in doing so, apply metaphors to the discourse. The visions or views of two opposing elements are not divergent or dichotomous; rather, they offer substitutes for the opposition through a process referred to as dualism. As Orlikowski (1991) proposed in her earlier paper, “The Duality of Technology,” this dualism is not mutually exclusive. The dualism originated from the admirable work by Giddens (1984), The Constitution of Society. Giddens’ structuration theory integrated two main streams of sociology: objectivism and subjectivism. It appears that the structuration theory adopts the notion of phenomenology, as it seeks to make explicit the implicit structure and meaning in human experiences (Sanders, 1982). Phenomenology searches for the essence of what an experience essentially is and is the intentional analysis between objective appearance and subjective apprehension. Structuration theory (the process of structuration of an organization) seeks a complementary essence in the structure of organization science and in the process of struggles between objectivism and subjectivism. Interestingly, the conflict of objectivism and subjectivism was reflected in metaphors, as Lakoff and Johnson (1980, p. 189) stated:

Objectivism and subjectivism need each other in order to exist. Each defines itself in opposition to the other and sees the other as the enemy. Objectivism takes as its allies: scientific truth, rationality, precision, fairness, and impartiality. Subjectivism takes as its allies: the emotions, intuitive insight, imagination, humaneness, art, and a “higher” truth…. They coexist, but in separate domains. Each of us has a realm in his [or her] life where it is appropriate to be objective and a realm where it is appropriate to be subjective.

Human players have very important roles in both phenomenology and metaphors due to their valuable experience. The key differentiator between objectivism and subjectivism is always human experience. Another important fact (usually overlooked by researchers) is that the use of metaphors appears in both the physical world and in the perceptual world (Harrington, 1991) because the term organization itself results from “dead” metaphors. Tsoukas (1991) describes the process in which metaphors “have become so familiar and so habitual that we have ceased to be aware of their metaphorical nature and use them as literal terms.” It implies that the metaphors of virtual organizations are “live” metaphors (Tsoukas) as we know “that these words are substitutes for literal utterances” that use dead metaphors (organization per se). Therefore, live metaphors are used to describe virtual organizations in another dimension, where we can do things that are not possible in the real world because the virtual world operates without the constraints of time and space, unlike the real world.

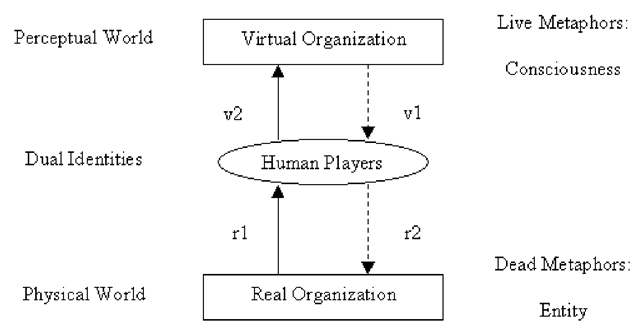

The process of structuration involves the reciprocal interaction of human players and institutional properties of organizations (Giddens, 1984); as Orlikowski (1991) pointed out, “the theory of structuration recognizes that human actions are enabled and constrained by structures, yet these structures are the result of previous actions.” Because we live in both real and virtual worlds, we have both objective and subjective understandings of each world—dual identities. Figure 1 shows the relationship between real organizations and virtual organizations in the presence of human interveners. Both real and virtual organizations consist of rule resource sets that are implicated in their institutional articulation, thus these rule resource sets act as structures of the organizations (both virtual and real), where a structure is the medium and the outcome of organizational conduct. The structural properties do not exist outside of the actions of the organizational actors. Therefore, structural properties, related to space and time, are implicated in the production and reproduction of the organizations. In other words, both real and virtual organizations undergo structuration across the different sets of dimensions of time and space based on the perspectives of each human player.

Figure 1. Dual identities of human players in both real and virtual organizations

The above model, which is adopted from the duality of technology of Orlikowski (1991), depicts four processes that operate continuously and simultaneously in the interaction between human players and both real and virtual organizations. These processes include (a) institutional properties, represented by arrow r1 (objective appearance of the real organization) and arrow v1 (objective appearance of the virtual organization), which are the medium of human players; (b) structures, represented by arrow r2 (subjective construction of the real organization) and arrow v2 (subjective construction of the real organization), which are the product of human players; (c) the interaction of human players in both worlds and the resultant influences on the social contexts of the real organization within which it is built and used (the direction of arrow r1 and v2); and (d) how the virtual organization is built and used within particular social contexts in a real organization (the direction of arrow v1 and r2).

In Figure 1, there are two structurations from human players: one for the real organization and the other for the virtual organization. The realms of virtual organization and real organization are objective while the consciousness of the human player is subjective. The process of structuration (Figure 1) involves the reciprocal interaction of human players and institutional properties of organizations (Giddens, 1984). As Orlikowski (1991) pointed out, “the theory of structuration recognizes that human actions are enabled and constrained by structures, yet these structures are the result of previous actions.” We have both objective and subjective understandings of each world (dual identities) because we live in both real and virtual worlds.

The maturity phase of the real organization (with its established tradition) and the fledgling state of the virtual organization (with its newly emerging phenomena) indicate that the objective appearance of the real organization (arrow r1) and subjective construction of the real organization (arrow v2) dominate the structuration process in modern organizations. Many observations show that the knowledge and experiences accumulated in a real organization enforce the formulation of the virtual organization in the abstraction process of efficient and effective goal-oriented activity (Mowshowitz, 1994). It is partly true that the creation of the virtual organization is only for the representation of the real organization in virtual space. A considerable amount of explanation arises from rethinking the basic assumptions of time and space. The real organization, whether tangible or intangible, is bound in time and space while the virtual organization, an imaginative concept established in computer hardware and software, is free from the constraints of time and space.

Barley and Tolbert (1997) defined an institution as “shared rules and typifications that identify categories of social actors and their appropriate activities or relationships.” As they explained their recursive model (institutions and actions), institutionalization involves the behavior of revision or replication of organizational abstracts (work procedures) and entails objectification and externalization of behaviors. In this sense, the successful functioning of a virtual organization is reaching insti-tutionalization in virtual space. Through this process, the virtual organization becomes stable and helps serve as the constitution where human players can follow their activities. Upon further inference, institutions from business processes of real organizations constrain human actors (constitutive nature, r1) who in turn construct institutions of virtual organization (constituted role, v2), and/or vice versa (from v1 to r2).

The above arguments provide complementary insights into the social process explained by the structuration theory (Giddens, 1984). In this theory,actions and institutions continuously interact, thereby determining the structure. The structuration theory lacks the explanation of how these interactions (revising and reproducing an institution or structure) are processed, although this is arguable as Giddens explains the role of reflection, interaction, and so forth. However, Barley and Tolbert (1997) clearly stated that their work, “the aim of institutional theory,” is “to develop the implications of structuration theory for the interplay between actions and institutions and to address the practical problem of how to study institutional maintenance and change in organizations.”

The authors believe that the results of this study are compatible with the belief of Barley and Tolbert (1997) that “the institutional perspective must come to grips with institutionalization as a process if it is to fulfill its promise in organization studies.” The focus of this study is the explanation of what is going on in a virtual organization. The result revealed by this research is a rich description of theoretical induction. A limitation of this process is that it only reflects one part of the recursive model of institutional theory (Barley & Tolbert).

CONCLUSION

Organizations today are usually faced with a turbulent environment that requires flexible and dynamic responses to changing business needs. Many organizations have responded by adopting decentralized, team-based, and distributed structures. Advances in communication technologies have enabled organizations to acquire and retain such distributed structures by supporting coordination among people working from different locations (Abuja & Carley, 1998). Thus, virtuality plays an important role to achieve above goals of current business environments. The virtuality of a virtual organization can be seen as an “emptying” of the organization, where emptying of information and knowledge has occurred in current communication technology (Giddens, 1984, 1990). IT (or information systems) generates and stores information that helps in the emptying (separation) of information from organizations. Knowledge, a supposedly higher format of information, is managed by knowledge-management systems (KMSs), another evidence of the emptying of knowledge from organizations. Because data, information, and knowledge of organizations are emptying from their organizations (i.e., can be stored and manipulated in information systems), the separation of the organization from its four-dimensional entity (time factor and three location factors: latitude, longitude, altitude) can be achieved in the form of a virtual organization (Giddens) if the rest of the components of the organization are implemented in network.

The approach of this paper is that organizational transformation is “the ongoing practices of organizational actors, and emerges out of their (tacit and not so tacit) accommodations to and experiments with the everyday contingencies, breakdowns, exceptions, opportunities, and unintended consequences that they encounter” (Orlikowski, 1996). The above statement is identical to the theoretical framework of this paper in that users of the system continuously interact with the system through producing, reproducing, and transforming work practices (Giddens, 1984).

Mowshowitz’s (1997) depiction of a virtual organization is limited to a computer with a communication tool or computer network that increases the efficiency and effectiveness of organization performance (Mowshowitz, 1994). This paper complements the virtual organization as a social system giving the new meanings of time and space. This study rethinks the philosophy of the virtual organization, providing insight into the concept of the duality of human identity. It is not only a lens for understanding virtual organizations, but also a sociotechnical understanding of virtual organizations through structuration.

KEY TERMS

Collaborative Culture: By their nature, virtual organizations foster camaraderie between members even in the absence of face-to-face communications. Since the built-in communications tools are so easy to access and use, relationships form between members who have not even met. A corporate culture forms out of friendship that produces a highly collaborative nature unlike traditional organizations where such extensive communicating is not required.

Complementary Core Competencies/The Pooling of Resources: The ease with which two members of a virtual organization can communicate allows them to pool their resources, even with members not directly involved in a specific project. Separate entities can quickly be called upon to provide secondary service or consult on a project via virtual channels.

Customer-Based/Customized Products: A virtual organization provides the unique opportunity to provide their customers with highly specialized products as per their specific needs. This can be accomplished through outsourcing work to a separate organization or through the use of a virtually connected interorganizational node located closer to the customer. Either way, it becomes simple to add a function based on the customer’s request and seamlessly integrate that function into the existing framework.

Electronic Communication: A vital concept to the virtual organization is the ability to communicate through purely electronic means, eliminating the need for physical contact and allowing the geographical dispersion of organization members. Online collaboration via e-mail, discussion boards, chat, and other methods, as well as telephone and facsimile communications, are primary contributors to the removal of time and space in this new organizational concept.

Explicit Goals: Similar to metamanagement, each member of the organization is charged with an explicit task to complete as it relates to the overall function of the organization. Often times, after this single goal is completed, the link between the organization and the entity is dissolved until a further need for it is realized. At this point, the link is reestablished.

Flexibility: Virtual organizations are, by their nature, flexible. Traditional organizational structures are rooted in the physical world and rely on structures, unalterable networks, and specific locations to function properly. Because of this, when it becomes necessary to introduce change into a specific organization, a barrier is reached where further alteration requires physical, costly modifications. A virtual organization is unhindered by these problems. These structures are designed so that they can operate regardless of time or place, independent of existing physical realities.

Functionally or Culturally Diverse: The nature of global diversity and the ability to locate organizational functions across the globe creates a diverse environment for the entire organization. Since members are all in different locations and charged with different tasks, diversity exists that is only found in the very largest multinational corporations.

Geographical Dispersion: The combination of virtual organization with IT allows groups of employees to make progress on one project while working in tandem with another group in a distant physical location. Because information can be shared and meetings can be held with the use of high-speed networks and computers, tasks can be carried out in the location that is most appropriate and germane to that function.

IT: Information technology is the crucial component of a modern virtual organization. Without advances in technology, many of the realities of today’s virtual companies would be merely science fiction. These components include the Internet, LANs (local area networks) and WANs (wide area networks) for business, e-mail and online chat and bulletin boards, and real-time video conferencing. These technologies allow smaller work groups as part of a larger company operate independently of each other across a room or the globe.

Open Communication: The foundation of a virtual organization is its communications components that exist in absence of face-to-face exchanges. A virtual organization can only survive if its members communicate freely through the provided channels between them, be they based on the Internet or more traditional telephone technologies. The organization cannot continue to function unless it is aware of what all its members are currently completing and often times, when communication is more closed, work that is being completed in tandem by more than one member can be hindered or brought to a halt.

Participant Equality: Each individual facet of a virtual organization is expected to contribute an equal amount of work toward a given goal, if appropriate. While the equality may not be measured best in quantity, it can be restated as effort and the successful completion of all tasks assigned to it, be they large or small. Since every task is considered to be essential as a part of the project, the equality comes in the addition of that piece to a larger puzzle.

Sharing of Knowledge: Members of a virtual organization collaborate to share their knowledge gained from individual activities performed. Since collaboration is facilitated through the communications channels that are afforded through the virtual organization, it is common to find “knowledge bases” or other database systems that contain information and documents pertaining to past experience.

Switching: The switching principle is a fundamental advantage that a virtual organization has over a traditional one. Because the links between organizational functions are largely electronic and nonphysical, it is easy to replace a weak component with a stronger one. Where this activity could be considerably expensive if the item in question was a physical supply chain, it may only be a change of suppliers for the virtual organization and can be made with a phone call and database edit, as opposed to a building project.

Temporary: Virtual organizations are often formed to fill temporary needs, only extending to the end of the specific project that is charged to them. In a manufacturing project, a virtual organization may be formed between the engineers who design the project, suppliers who provide the raw materials, and the factory who processes those into finished goods. At the end of that particular project, those alliances are dissolved as they are no longer necessary to benefit the three independent groups.

Trust: The lack of physical interaction places a higher regard to the trust that exists between each entity involved in the organization. Since fewer “checks and balances” can be placed on appropriate departments, management and other entities trust that they will complete the appropriate work on time or be straightforward about delays or problems. If two entities working on a project together separated by thousands of miles are unwilling to trust each other, the work slows and suffers to a critical point.

Vague/Fluid/Permeable Boundaries: As a continuation of flexibility, the virtual organization is characterized by vague boundaries as to the extent of its use and purpose. Since small tweaks can easily and largely affect the overall organization, it is quite possible to extend the boundaries of an organization so that they encompass new purpose, people, or control.