INTRODUCTION

This article describes research undertaken at the Scholarly Communications Lab of the College of Information and Computer Science at Long Island University in the area of higher education e-learning market in the United States. It is organized around three topics: a definition of e-learning and distance education; a description of the size, growth, and future outlook for this market; and the identification of some of the key growth drivers both historically and for the future.

The distant education market is now a mature market and has been around for a long while, with its antecedents established decades ago. The market has grown substantially in the last 10 years, and will continue to grow significantly, with an estimated market size of over $17 billion in 2010, representing a penetration rate of over 30% of the total higher education market in the United States. Many institutions of higher education have embraced some type of online programs, with 96% of universities with enrollments of 15,000 students having some e-learning programs. Major new entrants from the for-profit sector are now active in this marketplace. With the combination of new entrants and new technology advancements, the opportunities for value creation have increased while the nature of competition has intensified substantially.

BACKGROUND

According to Western Governors University (USA), distance learning and e-learning is simply: Education that takes place when the instructor and student are separated by space and/or time. The gap between the two can be bridged through the use of technology—audio tapes, videoconferencing, satellite broadcasts and online technology, just to name a few—and/or more traditional delivery methods, such as the postal service. (WGU, 2004)

As communications and computer technology evolve, the definition of distance learning continues to develop.

Asynchronous or time-delayed computer conferencing has given institutions the capability to network groups of learners over a period of time, allowing students in distance learning programs to be taught in groups rather than as individuals (Gunawardena & McIsaac, 2003).

Distance learning, before it evolved into primarily e-learning, has been around for a long period of time. It began in the second half of the 19th century with the exchange of print materials, assignments, and feedback by mail. Over the course of the 20th century, the development of radio and television made the delivery of additional materials (lectures and demonstrations) by electronic means possible. The 1950s saw the growth of a number of video projects that sought to identify expert science, math, and language teachers who could spread their expertise to students across a region or across the whole country. In 1989, Congress enacted the Star Schools legislation, intended to deliver quality instruction to largely rural or underserved areas. Among the Star School projects were three courses designed for adult learners, two of which used a studio teacher providing regular classes on topics ranging from job-seeking skills to skill-building needed to qualify for the GED. (www.ed.gov/prog_info/StarSchools/).

CURRENTLY CHANGING DEVELOPMENTS

More recent technologies have expanded the number of communication channels available to distant educators. Email and computer conferencing began in the early 1970s as part of the government sponsored ARPANET (Advanced Research Projects Agency Network) (Harasim, Hiltz, Teles, & Turoff, 1995). Although scientific work groups quickly adopted these communicative tools to advance collaborative activity at a distance, they were not available to educators and off-campus students for another decade. In education, these tools could permit learners to exchange and debate ideas. But only in recent years have educators recognized the potential of these tools to support a different model of distance education, a model built on more constructivist principles of learning. Over the 20th century, the technological possibilities have changed, although the pedagogical model has not (Tolmie & Boyle, 2000). Most distance courses that use the modern information handling technologies are still built on a transmission model in which instructors create material to be consumed by learners, and learners are given exercises and tests that they submit to the instructor demonstrating their mastery of the material; that they understand it, remember it, and can apply this knowledge in testing situations (Askov, 2003).

In the 1990s, new tools became available to the scientific community: the Internet and the Web. By the mid 1990s, these were made available to the broader public. Educators recognized the potential of these technologies immediately, and a few distance educators began to recommend a new model of education that emphasized the qualitative improvements in learning itself, if learners had ready access to a variety of electronic materials and were supported in examining and discussing these materials with other learners. These educators sought to distinguish this form of distance learning from more traditional forms by using new terms: distributed or flexible learning. (Bates, 2000) It is estimated that by the year 2012, schools and colleges will routinely use “computerized teaching programs and interactive television lectures and seminars, as well as traditional methods” (“Emerging,” 2003, p. 8). Videoconferencing and other technologies will also help enrich media and provide many benefits of face to face instruction (Wonacott, 2002).

In2003, the first in a series of annual reports by The Sloan Consortium on the state of online learning in U.S. higher education, “Sizing the Opportunity: The Quality and Extent of Online Education in the United States, 2002 and 2003″ was released. The initiation of this annual study emerged from a search for an authoritative answer to the question: “How many students are learning online?”

Market Size estimates. The answer determined by that first study was that for the fall 2002 term, slightly more than 1.6 million students took at least one online course at U.S. degree granting institutions. This same study asked institutions to predict the rate of growth (or decline) in their online enrollments for the following year, and respondents projected an average annual growth rate of 19.8%. This number was substantially above the annual rate of increase in the overall population of higher education students, whose annual growth has been estimated as between 0.8 and 1.3% (Allen & Seaman, 2006). It is evident that higher education administrators have been both optimistic and aggressive in their views of the growth of online learning in the U.S. This view of the marketplace has been validated, and significant investments into this market for e-learning courses have followed consistently. For example, the second annual study, “Entering the Mainstream, The Quality and Extent of Online Education in the United States, 2003 and 2004,” found that the overall growth in the number of online learners actually exceeded the optimistic projections of the previous year, increasing at a 22.9% rate, to reach 1.9 million online students for fall 2003 (Allen & Seaman, 2006).

The strength of this market in terms on new students, new courses, and new entrants continue unabated. In 2003, the yearly increase of about 360,000 new online learning students was matched by the results of the 2005 study, Growing by Degrees, Online Education in the United States, 2005, with more than 2.3 million students taking at least one online course during the 2004 fall term. Despite a lower percentage increase reported in 2005 of 18.2%, as there is an increasing larger base population, there are more and more students taking online courses and further there are increasingly more students taking online courses for the first time. This trend was further illustrated in the results the fourth annual Sloan Consortium study showing there has been no leveling in the growth rate and strength of this market. During the 2005 term higher education institutions taught nearly 3.2 million online students, an increase of about 850,000 students and a growth rate of 35%. 2005 marks both the largest increase in the number of online students and the largest percentage increase since these tracking surveys have begun. In 2005, the overall size of the higher education student population is sized at approximately 17 million with the number of students taking online courses at approximately 3 million or now representing nearly 17% of all higher education students (Allen & Seaman, 2006) (Table 1).

Table 1. Students taking at least one online course—Fall 2005

| Undergraduate | 2,621,713 |

| First Professional | 39,350 |

| Graduate | 443,827 |

| Other for-credit | 75,159 |

| Total | 3,180,050 |

Using our current estimates of growth, the current 2007 market size is estimated between 4.5 to 5.0 million students enrolled in e-learning courses or 25% to 30% of the overall higher education market. The demand for this form of education is continuing steadily and strongly.

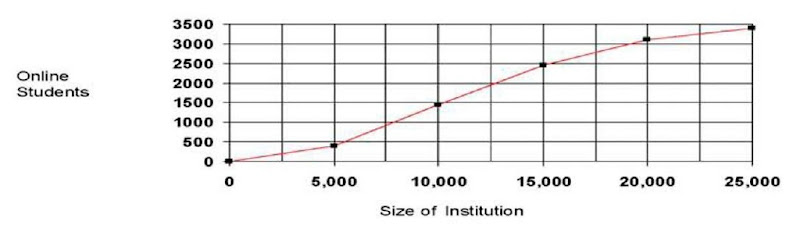

In meeting this strong and increasing demand for online education, it appears that the large universities have responded first and most strongly. The size of an institution has a clear impact on the average number of online students at institutions. The largest institutions (defined as institutions with enrollments of 15,000 or more), for example, are each teaching an average of more than 3,200 online students at the undergraduate level alone. This compares to about half that amount (1,500 online students) for the next smaller-sized institution type (those with overall enrollments between 7,500 and 14,999). It is estimated that currently the average number of online students enrolled is proportional to the size of the institution (Kariya, 2003). In 2005, for each institutional size type, the average number of students is around 20% of the lower range of each size type, except for the smallest of the institutions (those with less than 1,500 total students) which is below this level, while the largest institutions are slightly above this average. However it is estimated, the proportion of the student population that is taking at least one online course has begun to reach a level that institutions of all sizes must address this as an important educational issue (Table 2).

The Doctoral/Research and Master’s institutions have the largest average online total enrollments since they are more likely on average to be the largest schools. Associates institutions offering 2 year only Associate Degree programs also have a sizable average online enrollment (nearly 800 undergraduate students per institution), but the large number of Associates institutions is what accounts for the large number of online students at such schools (Allen & Seaman, 2006) (Table 3).

Course offerings and institutional profiles. Evidence has shown in the past a very uneven distribution of online course and program offerings by type of institution. Public institutions and the largest institutions of all types have consistently been at the forefront of online offerings. Those that are the least likely to offer online courses, and typically have the most concern about online education in general, have been the small, private, 4-year institutions. It must be taken into account that not all schools offer online courses, and not all schools that have online courses offer fully online programs (Hickman, 2003). Examining the pattern of online offerings does show some interesting patterns when the results are compared to the distribution of online students. For example, Doctoral/Research institutions, which enroll 13% of all online students, have the greatest penetration of offering online programs as well as the highest overall rate (more than 80%) of having some form of online offering (either courses or full programs). Although Associates schools have by far the largest contingent of online students, they trail both Doctoral/Research and Master institutions in the proportion with online programs or any type of online offering.

Table 2. Mean undergraduate online enrollment by size of institution—Fall 2005

Table 3. Mean number of online students per institution—Fall 2005

| Doctoral /Research | Masters | Baccalaureate | Associates | Specialized | |

| Undergraduate | 1 01 7.1 | 988 3 | 148.7 | 797 S | 84.2 |

| Professional | 21.7 | 1.1 | O.B | 2.6 | 10.3 |

| Graduate | 520 6 | 365 5 | 14.1 | 0 3 | 47 1 |

| Other for credit | 16.9 | 9.7 | 0 6 | 23.3 | 18 |

More than 96% of the very largest institutions have some online offerings, which is more than double the rate observed for the smallest institutions. The proportion of institutions with fully online programs rises steadily as institutional size increases, and about two-thirds of the very largest institutions have fully online programs, compared to only about one-sixth of the smallest institutions. Doctoral/Research institutions have the greatest penetration of offering online programs as well as the highest overall rate (more than 80%) of having some form of online offering. The proportion of institutions with fully online programs rises steadily as institutional size increases, and about two-thirds of the very largest institutions have fully online programs, compared to only about one-sixth of the smallest institutions. Additionally, Doctoral/Research institutions are far more likely to have online programs than are Baccalaureate institutions (Table 4).

Market competitive issues. With markets no longer defined by geography and as the quality and quantity of online courses increases, the trend toward electronic learning is perhaps entering a new era of growth and competition in higher education.

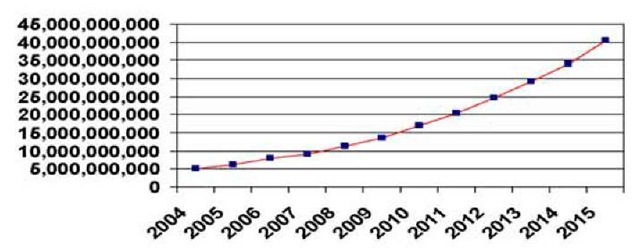

According to a 2004 report by Eduventures, while enrollment in fully online distance education programs is growing at 30% (Gallagher, 2004), the average tuition per student is approximately $5,500 and represents a total market of about $5 billion in tuition revenue for 2004. Our estimates suggest that the fully online distance education will represent a market of $17 billion by 2010. The overall revenue market size for fully online education is expected to grow approximately 38% in 2004. The estimated growth rates for the number of students enrolled in online education programs will remain above 20% for at least the next 3 to 5 years, slowing as the market matures further (Table 5).

It is estimated that undergraduate student enrollment programs will drive approximately 73% of revenues in the online education market in 2004. The majority of students in online education programs are undergraduate students. However, the share of the online market regarding graduate level education is greater than its share of campus-based education, mostly due to the disproportionate number of working adults in graduate programs. It is expected that the undergraduate market will continue to grow, while the graduate-level programs will experience a surge in the coming years due to the current undergraduates continuing their education after obtaining their undergraduate degree.

For-profit institutions have taken a significant market share of the online education market, clearly disproportionate to their share of higher education overall market. For-profit institutions were early entrants and aggressive investors in this market and these factors coupled with their programs typically priced higher than nonprofit institutions, have permitted the for-profits a command of nearly 44% of the online market revenues in 2004, up from 30% in 2000. In fact, online education revenues in the for-profit section of the market have grown by more than 50% per year for several years and have grown at an estimated 25 to 30% per year through 2006. The for-profit sector represents significant and sustained competition in the online higher education market. As the overall higher education market moves to a more online offering, for-profit institutions will become a more significant player in the overall market.

Table 4. Online offerings—Fall 2005

| Doctoral/Reseoirch | Masters | Baccalaureate | Associates | Specialized | Total | |

| Online Programs | 55.7% | 43.6% | 17.2% | 31 2% | 2S.O% | 31 .4% |

| Courses Only | 24.9% | 33.9% | 24.0% | 39.3% | 22.7% | 31 .5% |

| No Online | 19 4% | 22.5% | 58.8% | 29.0% | 51 .3% | 37.0% |

Table 5. Fully online distance education enrollment

FUTURE TRENDS

In reviewing the development of the last 20 years of the online higher education market, we see the growth of this market in three distinct phases. Each phase is characterized by a different competitive advantage. These are: Phase1. Technology Superiority; Phase 2. Breath of Content Offerings; and Phase 3. Brand equity.

1. Technology Superiority 1980-1997

The 1980s and early1990s represented the pioneering days of online distance education. With the emergence and availability of the World Wide Web, this set the stage for colleges and universities with a history of distance programs to then expand and tap into a broader market. During this phase, student enrollment grew exponentially as leading colleges launched and marketed new and innovative programs.

• University of Phoenix launches online division via Compuserve

• Institutions with histories of distance education and outreach development Web-based courses

• Early course management system software emerges

This phase of development is characterized by a competitive landscape where the leaders made significant investments in the technology platforms and software systems that allow for the production and distribution of online education courses. In this initial phase, those institutions that held the technology to develop these courses held a significant competitive advantage. The cost of technology was a significant barrier to entry, and those organizations that had access to capital and a taste for risk represented the early leaders. With this profile it is not surprising that the for-profit institution gained early and significant market share from the onset.

2. Building the Inventory of Course Offerings 1998-2003

The promise of online education as a market was enhanced by the Internet “Gold Rush” of the late 1990s. Private investors began to invest aggressively in for-profit universities and software providers in the higher education market with more than $1.2 billion in capital in 1999 and 2000 alone, the majority of which was devoted to e-learning. This capital provided not only marketing dollars and infrastructure to enable distance education to take off, but during this phase most importantly much of this capital was used to develop a strong and robust portfolio of course offerings. These course offerings were developed by for-profits both on their own and in partnership with other higher education institutions. Nonprofit educational institutions built this inventory of courses by offering incentives to their faculty for the production of courses, while developing training programs for faculty to learn this new form of distance education.

With technologies and a robust inventory of courses in place, these years also triggered the initial boom in consumer awareness of online education. Marketing and organizational development became the pivotal factor in defining competitive winners and losers in this phase. For example,

• University of Phoenix spins out an its online subsidiary in an initial public offering (IPO), the first of its kind in this area

• Nonprofit universities such as NYU, Columbia, and the University of Maryland University College create for-profit spin offs to tap Internet course opportunities and have the access to capital available in this sector

• In order to leverage their investments in technology and content, collective advertising and marketing expenditures for online education top $200 million at for-profit institutions

• The number of colleges offering online education programs balloons into the thousands

• U.S. News and World Report launches an annual e-learning section evaluating online education programs.

Course development still continues today. Online courses now can be made available, but the faculty training and incentives needed to develop these programs are significant, particularly for those institutions that have not embraced online programs. We estimate that this development of content is still a barrier of entry for institutions without substantial programs now in place and will represent increasingly substantial investments for these institutions to “catch up” and try to level the competitive landscape for themselves.

3. Market Development and Brand Equity 2004 and Forward

Colleges and universities at all levels have utilized online education to tap new markets of working adults for whom participation in traditional postsecondary education was inconvenient or impossible. Institutions recognizing the potential of online education have made important investments not only in infrastructure, but also in faculty training, student services, and marketing to participate in the growth of the online education market.

Recognizing the growth opportunity, institutions are investing more heavily than they have in the past. Effective marketing is becoming more targeted and segmented as distinct value propositions, areas of focus and brands emerge. Additionally, many of the students of the early boom years are graduating, creating a powerful new word of mouth and viral marketing channel. For instance,

• Majority of degree-granting institutions, particularly large institutions over 15,000 students (at 96% for this group), are offering online education programs

• Capella University was selected by Wal-Mart as a preferred education provider

• University of Phoenix Online enrollments approach 100,000, nearly 50% of all enrollment at the nation’s largest private university

• Nonprofit institutions partner with for-profit education experts such as UNext, Capella and Collegis in order to launch best-of-breed online offerings.

Many of these trends in higher education will influence the future of distance learning. Student enrollments are growing and with this learner profiles are changing, and students are becoming more demanding in the quality, breath and convenience of offerings, and as a result are shopping for educational programs that can be easily tailored to their needs (Brodsky, 2003). The Internet and other information technology devices are becoming more ubiquitous while technological fluency is becoming a common expectation. As these expectations are common and as the technology is broadly available, we see the competitive landscape moving beyond technology and content, and residing much more around the reputations of the online programs themselves. Though innovation will always be a factor, as will the breath of content offering, the key emerging competitive differentiate is likely to be the perceived quality of the offering and the support services around those programs. Customers will expect, demand, and evaluate the value of these online offerings based upon their complete experience, including the market positioning, the program support, and administrative functions, as well as the technology and quality of the faculty and content (Bates, 2003).

CONCLUSION

Technological advances and increased fluency will continue to open opportunities for distance education. Although higher education institutions are changing to favor distance education, the complexities of major transformations will require substantial investment and planning. As Bates (2000) suggests, perhaps “the biggest challenge [in distance education] is the lack of vision and the failure to use technology strategically” (p. 7). Though this challenge is understandable, given the complexity of the issues involved, institutions which now wish to enter this market will find the barriers to be substantial. Universities without e-learning programs may easily find the distribution technologies that will launch their programs, but their challenges will be in building an inventory of courses, faculty competent in this new educational media, the creation of adequate administrative and support services, and most importantly the need to market and build brand equity in their new e-learning programs. Further, institutions currently active will strengthen their distance-learning strategic plans by identifying and understanding distance-education trends for new student enrollments, faculty support, and larger academic, technological and economic issues (Howell, Williams, & Lindsay, 2003). The gap will increase between the current players and new aspiring entrants, who will need to be willing to make significant financial investments with a clear development plan, if they hope to catch up.

KEY TERMS

Collaborative Learning Online: Technologies that link together people in several locations so that they can interact with one another.

Computer-Based Learning: Refers to the use of computers as a key component of the educational environment. Broadly refers to a structured environment in which computers are used for teaching purposes.

Distance Education: The process of extending learning, or delivering instructional resource-sharing opportunities, to locations away from a classroom, building or site, to another classroom, building or site by using video, audio, computer, multimedia communications, or some combination of these with other traditional delivery methods.

Distance Learning: Courses in home: education for students working at home, with little or no face-to-face contact with teachers and with material provided remotely, for example, by e-mail, television, or correspondence.

E-Learning: Learning using electronic means: the acquisition of knowledge and skill using electronic technologies such as computer- and Internet-based courseware and local and wide area networks.

Higher Education: Education provided by universities, vocational universities and other collegial institutions that award academic degrees.

Online Learning: Learning via educational material that is presented on a computer via an intranet or the Internet.

Web-Based Training: Also referred to as “online courses” or “Web-based instruction,” a form of learning in which the training material is contained on Web pages on the Internet or an intranet.