INTRODUCTION

An increasing number of traditional colleges and universities, responding to marketplace pressures, are offering online courses and degree programs. According to Weil (2001), 54% of U.S. higher education institutions offer e-learning courses. Many AACSB-accredited business schools provide courses and complete degree programs online. New schools have been created that exist solely in cyberspace (Peltz, 2000). Students can complete undergraduate online degree programs in fields as diverse as nursing, business, engineering, and technology.

Possible reasons for schools offering online courses and degree programs include: increasing revenues and credit hour production; better utilization of limited resources; serving an expanded geographic area or student population; and serving the existing student population differently. Students may take online courses due to their perceptions of location convenience, time convenience, cost, and quality.

Some online courses have been implemented so quickly that insufficient time has been available to allow in-depth assessment of the desires, interests, and concerns of their potential direct customers, that is, students. The study described here was developed to identify students’ expectations and current perceptions of online courses and degree programs. The results are expected to facilitate effective planning and development of these courses and programs in the future. The intent is to study the next generation of online learners. This group’s perceptions of online coursework are important for course providers as they consider ways to maintain and enlarge their programs, perhaps expanding to meet the needs of younger, more traditional students.

BACKGROUND

Online courses are a form of distance education. Today’s widespread availability of the Internet has made online courses and degree programs available to students around the globe. Many traditional colleges and universities have decided to add online coursework so that they can be competitive with the large number of programs now available from private enterprises set up for this purpose. Several issues have emerged related to this instructional delivery format, and studies are now being reported related to advantages and disadvantages of this type of education.

As with other forms of distance education, convenience has been widely quoted as a primary reason for students taking online courses. Another reason is the self-paced nature of many online courses, which allows for a variety of student schedules and comprehension rates. Availability of coursework regardless of the student’s physical location is another reason it is used; it would be possible for students in remote locations to take these courses as long as they had the necessary technology. It is also possible that online courses provide more up-to-date materials than that found in some traditional courses and text topics, due to the ease of making changes to Web sites rather quickly (Accetta & Wind, 2001). Another factor that may make online courses an appealing option is that a person’s age or physical limitations may be less likely to prevent the person from succeeding in this format (Brown, 2000).

Faculty who teach online courses may find it rewarding if they enjoy using new technology and also enjoy the challenge of adapting to a different form of course delivery.

Critics of online courses point out that a Web-based educational program has at least one disadvantage in that it does not provide a forum for physical contact and live debate between students and faculty. Representatives of some elite universities claim that it is impossible to replicate a classroom environment with online courses. Harvard University’s Professor W. Earl Sasser indicated that Harvard does not plan to offer an MBA degree online because it would distract from the residential experience (Symonds, 2001). Kumar, Kumar and Basu (2002) cite “strong evidence that students perceive interaction, student-to-student and student-to-instructor, to suffer as a result of virtual education” (p. 140). But some information technology professionals argue that there is little difference between getting a degree on-campus or over the Web. Robert Baker, a systems consultant, observes that students taking online courses are not isolated and can get to know faculty and other students by using online discussion boards (Dash, 2000). Schooley (2001) states that online university courses facilitate communication with the instructor and among classmates.

Another concern is that online coursework may worsen the so-called “digital divide” between students in higher-income versus lower-income families, as those with higher incomes will have more Internet access (Accetta & Wind, 2001). However, libraries and schools have increased Internet access availability to people at all income levels and at locations worldwide.

Some questions also exist about the cost of taking online courses. Some students believe that an online course is a less expensive method, and some course providers believe it to be a cost-effective method of course delivery. As a point of comparison, Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business offers MBA degrees that provide about 65% of the work online and about 35% of the work in residency. Duke charges up to $90,000 for the program versus $60,000 for its traditional on-campus MBA degree program (Symonds, 2001).

One critical indicator of program success or failure is the extent to which graduates are accepted in the job market. Quigley (2001) cites a Business Week magazine survey reporting that most recruiters are skeptical of skills of graduates of online business schools. Many executives do not feel that online degree programs have been offered long enough to prove themselves with on-the-job performance of MBA degree graduates.

Some educators are concerned about the rapid growth of online degree programs. Others have questioned the superiority of online courses when compared with classroom-based courses. Online courses may be developed by curriculum specialists with little or no participation from the faculty member who will conduct the class. Much e-learning is self-directed and not led directly by faculty members. A fear is that faculty members will no longer be curriculum developers and participants in intellectual debates within their disciplines. Accetta and Wind (2001) suggest that “faculty will become mere shepherds herding their passive sheep through pre-prepared fields of outdated and insubstantial information.”

Faculty members are also concerned that students will not get the same campus experience that is provided to students who are enrolled in traditional on-campus degree programs. Some schools require that students check in online for a specified number of times each week. Many programs also require some amount of on-campus time, as well as meetings via conference calls. Some programs incorporate team projects that require students being together during specified points during the course. Some programs require one or more retreats in a traditional lecture/seminar format.

Many faculty members are skeptical about the quality when the time period required to obtain a degree is very short. For example, the American Intercontinental University-On-line (2002) advertises that a Master’s degree can be earned in as little as 10 months.

There are also concerns about technical, administrative, and pedagogical issues that arise as faculty consider moving from a traditional classroom environment into a Web-based environment. Logistical concerns relate to providing students with the same level of support (e.g., library, advising) in both environments. Pedagogical considerations involve issues relating to management of course quality and control over the learning environment.

Wonacott (2000) states that instructional design should be the primary factor in implementing online coursework rather than the appeal of technology. He also mentions that students and instructors need appropriate training and guidance if this type of instruction is to be effective.

STUDIES OF EXISTING ONLINE COURSES AND PROGRAMS

Many reports have indicated typical students are “adult learners”. Typical participants are between 25 and 50 years of age and are taking online courses either to learn something new or to update their skills (Grill, 1999).

Studies have also indicated that students were more satisfied with online courses when there was more interaction with the course instructor. Interaction with other students was also a factor leading to more student satisfaction (Fredericksen, Pickett, Shea, Pelz & Swan , 2000).

Several comparison studies have been conducted between online and traditional on-campus courses, and most have found no statistically significant difference in test performance and grades. A greater degree of active learning in both settings increases performance and student attitude (Hall, 1999).

Studies of online coursework are being conducted in several countries. For example, one study compared “Anglo-Saxon” students in five countries to “Asian” students in nine countries to see if cultural differences existed related to the use of the Web as a learning environment. Some differences existed in the comfort level of various instructional formats. More Asian students liked the Web environment because of the innovative learning possibilities, while Anglo-Saxon students were more comfortable with the use of discussion groups (Chin, Chang & Bauer, 2000).

POTENTIAL FOR ONLINE COURSEWORK FOR FUTURE STUDENTS

Schools providing online courses and programs will eventually need to expand the attractiveness of their programs to additional markets in order for their programs to remain viable. Since the current programs are predominantly used by students who are older than the traditional fulltime college student, an initial step would be to determine the perceptions of the next group of college students regarding these programs. To obtain data related to perceptions of online courses by upcoming college students, a survey instrument was distributed to almost 400 students enrolled in high school business courses. Although participants in existing online courses and programs are older, educational institutions should understand the needs and perceptions of other constituencies if they want to expand their enrollments. These current high school students could represent a large potential target market in the future that will be increasingly computer literate, which would enable more students to take advantage of online coursework.

Demographics

A total of 381 high school students participated in this study. Slightly more than 71% of these students were juniors and seniors. A majority of the participants (58.78%) were female.

A high percentage of students (88.97%) indicated that they have access to a computer at home, which could have a direct effect on ability to participate in online courses. Lack of access to a computer could affect perceptions. A comparison of accessibility by gender showed that the difference between genders was slight (Table 1).

Current Status Regarding Taking Online Courses

Students were asked to describe their current status regarding taking a course online and were allowed to select more than one response. As shown in Table 2, about one-fourth of the respondents indicated that they would not take an online course. There was little difference between males and females on this issue. Not surprisingly, very few had already taken or were currently taking a course online.

Ratings of Issues’ Importance

The remainder of the survey had two parts, each with a listing of issues for students to consider. Thirty-eight students failed to respond to a majority of the questions in this part of the survey and were eliminated from further calculations.

In the first section, students were asked to indicate how important each identified issue was to them in deciding whether to take a course online or on-campus. A Likert-type scale was used, with 1 representing “not at all important” and 5 representing “extremely important”. A mean was calculated as a basis for determining which issues were considered rather important (defined as a mean of at least 4.0)

Ratings That a Characteristic is More Likely True for Online versus On-Campus

For the second section, students were asked to consider the same issues as in the previous section but to indicate the likelihood that each issue was a characteristic of an online versus on-campus course, with 1 representing “much more likely in an online course” and 5 representing “much more likely in an on-campus course”. A mean was calculated to identify which issues were considered much more likely in an online course (defined as a mean of no greater than 2.0) and which were considered much more likely in an on-campus course (defined as a mean of at least 4.0). As shown in Table 4, three issues had a mean greater than 4. Only one issue, “Submitting assignments electronically,” had a mean below 3.0.

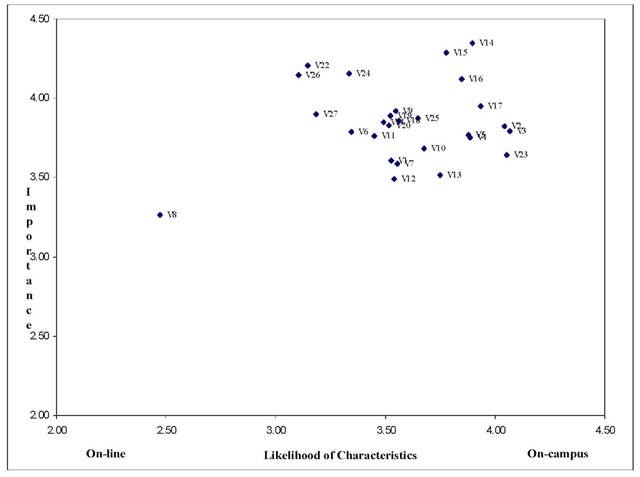

A cluster plot or “scatter diagram” was developed to illustrate the relationship between the two parallel sets of variables used in the study. As shown in Figure 1, all but one of the items were clustered in the upper right corner, which represents the section for higher importance and higher likelihood that the characteristic would be in an on-campus course. As discussed earlier, the only item in the left side of the diagram was “submitting assignments electronically.”

Table 1. Access to a computer at home by gender

| Gender | Percentage with Access |

| Male | 89.03 |

| Female | 88.50 |

Table 2. Current status regarding online courses

| Status Regarding Online Courses | Percentage of All Respondents |

Percentage of Male Respondents |

Percentage of Female Respondents |

| I would not take a course online. | 24.87 | 24.52 | 24.78 |

| I would consider taking a course online. | 58.20 | 56.77 | 58.41 |

| I would like to take a course online. | 28.04 | 26.45 | 28.76 |

| I plan to take a course online. | 6.35 | 6.45 | 6.19 |

| I am currently taking a course online. | 0.26 | 0.65 | 0.00 |

| I have completed a course online. | 0.49 | 1.94 | 0.00 |

The issues identified as most important were given further review, since those issues were not given particularly strong ratings as either online or on-campus options. Issues identified as most important in Table 3 are shown again in Table 5, along with an identification of their means for the comparison of “much more likely in an online course” versus on-campus. Table 5 indicates a tendency toward likelihood in an on-campus course for all of the issues identified as most important. All had means greater than 3.0, which is the midpoint of the scale where 1 represented much greater likelihood in an online course and 5 represented much greater likelihood in an on-campus course.

FUTURE TRENDS

Large increases are occurring in the availability of online courses and college degree programs, both at the undergraduate and graduate levels. Many traditional universities are adding online coursework to their offerings in an effort to maintain student enrollments. consequently, these institutions are concerned about the best methods for providing equivalent course content online.

Significant growth in online programs could lead to an eventual reduction in on-campus course offerings at universities.

Students are becoming increasingly competent in the use of computer technology. Future students, therefore, can be expected to be better prepared and possibly better candidates for online programs.

CONCLUSION

Students who participated in this study indicated that all the specified issues were perceived to be important (a mean greater than 3.0 using a 1 to 5 scale). All but one of the issues were perceived to be more likely to be characteristic of an on-campus course. Educational institutions need to begin considering the needs of this next generation of potential students in order to expand or maintain online course offerings in the future.

The fact that students in this study rated “knowledge gained” as their most important issue in a course or degree and also rated it more likely to be characteristic of an on-campus than an online course indicates that institutions wanting to increase the number of online students might need to look for documentation of high levels of knowledge gained through online course delivery. In addition,studies should be done to determine the specific features and programs that would be the best fit for these students in an online learning environment.

Table 3. Issues considered important in making course environment decisions

| Issue | Mean |

| Knowledge gained | 4.35 |

| Skills acquired | 4.29 |

| Access to information (resource materials) | 4.20 |

| Time required to complete coursework | 4.16 |

| Costs of tuition and fees | 4.13 |

| Schedule flexibility to accommodate work responsibilities | 4.13 |

Table 4. Issues that are much more characteristic of an on-campus course

| Issue | Mean |

| Opportunity for live interaction/discussion among students | 4.07 |

| On-campus exams | 4.05 |

| Opportunity for live interaction/discussion between faculty and students | 4.04 |

Figure 1. Comparison of importance with likelihood of being on-campus versus online

Table 5. Important issues related to online versus on-campus instruction

| Issue | Mean |

| Knowledge gained | 3.90 |

| Skills acquired | 3.78 |

| Access to information (resource materials) | 3.15 |

| Time required to complete coursework | 3.33 |

| Costs of tuition and fees | 3.85 |

| Schedule flexibility to accommodate work responsibilities | 3.10 |

Students’ perceptions of online programs should continue to be monitored by institutions wanting to increase their participation in these programs.

KEY TERMS

Distance Education: A form of instruction in which a geographical separation exists between instructor and students; it may be same time/different place or different time/different place. Various types of technology may be used as part of this form of education, with more technology required for the same-time format.

Distance Learning: The intended outcome of distance education, characterized by learning through audio-visual delivery of instruction that is transmitted to one or more other locations that may be live or recorded instruction but does not require physical presence of an instructor and students in the same location. Current technology used for distance learning includes text, images, and audio and/or video signals.

E-Learning (Electronic Learning): A form of learning that involves “electronic” or technology-based delivery of learning; examples of forms of delivery include individual computer-based delivery, Internet/Web delivery, and virtual classroom delivery. Media can be in many forms, including videotape and DVD, CD-ROM, satellite transmissions, interactive television, and various Web-based media (Internet, intranet, extranet).

Off-Campus Course: A course offered at a business location, satellite center, or other site other than the main campus of an educational institution.

On-Campus Course: A course offered wholly or in part on the main campus of an educational institution. An on-campus course is typically offered in a traditional lecture/discussion environment, but may include procedures and methodology associated with a hybrid online course.

On-Campus Degree Program: A prescribed program of studies leading to a degree conferred by an educational institution wherein the majority of courses are on-campus courses. (See definition of on-campus course.)

Online Course (Fully and Hybrid): An online course may be either a fully online course or a hybrid online course. A fully online course is offered in a format where its content, orientation, and assessments are delivered via the Internet and students interact with faculty and possibly with one another while using the Web, e-mail, discussion boards, and other similar aids. A hybrid online course meets one or more of the following requirements for students: (a) access to the Web to interact with the course content, (b) access to the Web to communicate with faculty and/or other students in the course, (c) on campus for orientation and exams, with other aspects of the course meeting the requirements for a fully online course.

Online Degree Program: A prescribed program of studies leading to a degree conferred by an educational institution wherein the majority of courses are online courses. (See definition for online course.)