Introduction

New public management and the more recent concept of new public governance have become the dominant management doctrines in the public sector. Public organizations have become increasingly network-like units with various governance relations with actors from the public, business, and voluntary sectors. Their organization is based more on networks than on traditional hierarchies, accompanied by a transition from the command-and-control type of management to initiate-and-coordinate type of governance.

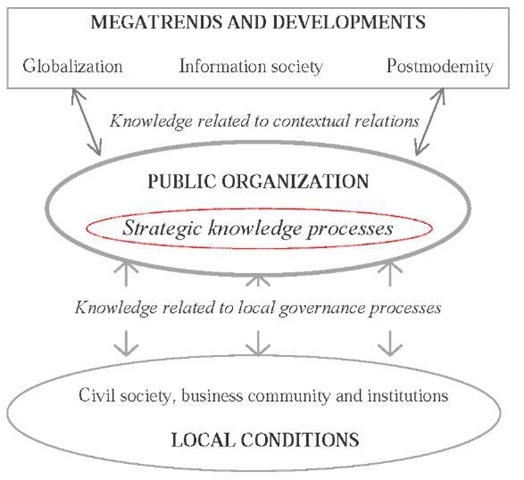

Among the most critical factors in this transformation is knowledge, for most of what has happened has increased the overall demand to create and process knowledge, and to utilize it in the performance of governmental functions. The success of public organizations depends increasingly on how efficiently they utilize their knowledge assets and manage their knowledge processes in adjusting to local and contextual changes, as illustrated in Figure 1 (cf. Gupta, Sharma, & Hsu, 2004, p. 3; Skyrme, 1999, p. 34, Fletcher, 2003, pp. 82-83). This requires that special attention be paid to strategic knowledge management.

In the early organization theories of public administration, knowledge was predominantly conceptualized within the internal administrative processes, thus to be conceived of as bureaucratic procedures, rationalization of work processes, identification of administrative functions, and selected aspects of formal decision making. New perspectives emerged after World War II in the form of strategic planning and new management doctrines. The lesson learned from strategic thinking is that we need information on the external environment and changes therein in order to be able to adapt to and create new opportunities from these changes (see Ansoff, 1979; Bryson, 1995). As the complexity in societal life and related organizational interdependency has increased due to globalization and other trends, new challenges of managing organization-environment interaction also emerged (cf. Skyrme, 1999, p. 3).

Figure 1. The public organization as an institutional mediator

background

The branch of management doctrine that became known as knowledge management (KM) reflected actual changes and new ideas in the business world. Classic works that inspired later developments included Polanyi (1966) and Drucker (1969). During the 1980s knowledge became widely recognized as a source of competitiveness, and by the end of the 1990s, knowledge management had become a buzzword. Among the best-known thinkers who contributed to the rise of this field are Peter Senge (1990), Ikujiro Nonaka and Hirotaka Takeuchi (1995), Karl-Erik Sveiby (1997), and Thomas A. Stewart (1997). (For more on the evolution of knowledge management, see Barclay & Murray, 1997; Gupta et al., 2004, pp. 8-10.) It is becoming common understanding that in essence knowledge management is about governing the creation, dissemination, and utilization of knowledge in organizations (Gupta et al., 2004, p. 4; Lehaney, Clarke, Coakes, & Jack, 2004, p. 13).

Knowledge cannot be managed in the traditional sense of management. The processing and distribution of information can surely be managed, but it is only one part of the picture. The other concerns knowledge and especially managers’ ability to create conditions which stimulate active and dynamic knowledge creation, learning, and knowledge sharing within the organization (e.g. Nonaka, Toyama, & Konno, 2000). To systematize this picture we may say that knowledge management includes four core areas (cf. Gupta et al., 2004; Lehaney et al., 2004):

• Information Management: Managing data and information, and designing information and knowledge systems

• Intellectual Capital Management: Creating and utilizing knowledge assets, innovations, and intellectual capital.

• Knowledge Process Management: Organizing, facilitating, and utilizing sense-making and other knowledge processes.

• Organizational Learning: Creating learning and knowledge sharing environments and practices.

Traditionally the most widely applied areas of knowledge management in public organizations used to be data and transaction processing systems, and management information systems serving mainly internal administrative functions. Yet, since the 1980s authorities started to facilitate the exchange of information by local area networks, followed by the Internet revolution of the 1990s. In the early 2000s the knowledge management agenda has focused increasingly on knowledge sharing and learning, and in inter-organizational network and partnership relations (e.g., Wright & Taylor, 2003). As reported by OECD (2003, p. 4), knowledge management ranks high on the management agenda of the great majority of central government organizations across OECD member countries, followed with some time lag by regional and local authorities. Many public organizations have even developed their own KM strategies. The leading countries in this respect include France, Sweden, Finland, and Canada (OECD, 2003, pp. 28-29).

As for more operational actions, there has been a wave of intranet projects at all levels of public administration since the late 1990s. The result is that some 90% of state agencies surveyed by OECD in the early 2000s had their intranets in place. Sectors that really stand out as being well above the OECD average include organizations in charge of finance and budget, of justice, and of trade and industry (OECD, 2003, pp. 20-30). Intranet projects in the public sector aim at creating an Internet-based computer network to securely share information or operations between politicians, administrators, and other employees. Extranet extends such a network outside the organization—that is, to users, partners, service providers, and other stakeholders. Many public organizations in different countries and at different institutional levels have set up such extranet and intranet projects. For example, New York City established in the early 2000s the Human Services Extranet (later renamed the Integrated Human Services Proj -ect) to link the city agencies with human service contractors. Similarly, in 2003 the Queensland Government, Australia, established a project aimed at enhancing the effectiveness of e-government service delivery, which was supported by a government-wide extranet. Such projects have been numerous in the public sector since the early 2000s, indicating a transition from information management towards genuine knowledge management. Yet, it is equally true that many public organizations have been slow to embrace knowledge management and knowledge technologies.

focusing on the strategic aspect

Combining strategic thinking with knowledge management brings us to the very core of the life of organizations. Strategic knowledge management is a set of theories and guidelines that provides tools for managing an organization’s knowledge assets and processes of strategic importance for the purpose of achieving organizational goals. It is in this sense about the development of an organization-wide knowledge management capability (Katsoulakos & Rutherford, 2005). The basic idea of strategic knowledge management in the public sector is to ensure that public organizations are capable of high performance by utilizing knowledge assets and knowledge processes when interacting with their environment.

What is essential in strategic knowledge management is that it needs to be ‘strategic’ in the true sense of the word, as opposed to ‘operational’. Public employees sometimes have a tendency to view their knowledge requirements from the point of view of their current work practices. At an organizational level, too, there is sometimes a temptation to map out the future on the basis of current strengths and well-defined short-term challenges. The strategic approach to knowledge aims to overcome such inertia and narrow perspectives by creative knowledge processes, which help to transform views from introspective to outward-looking, from resources to outcomes, and from formal duties to actual impacts and customer satisfaction.

In the knowledge management literature, knowledge has primarily been approached either as an object or a process (cf. Sveiby, 2001). The main focus of public organizations is on knowledge processes framed by certain institutional arrangements. Among the most important of these are the political dimension and democratic control and legally defined functions, competencies, and procedures within territorially defined jurisdictions (for more on KM in the public sector, see e.g. BSI, 2005). This theme will be discussed next.

facilitating strategic knowledge processes

Public organizations possess and process a huge amount of information in their internal operations and external exchange relations. This is why the most important function of their knowledge management practice is to manage knowledge processes and to support knowledge-sharing practices.

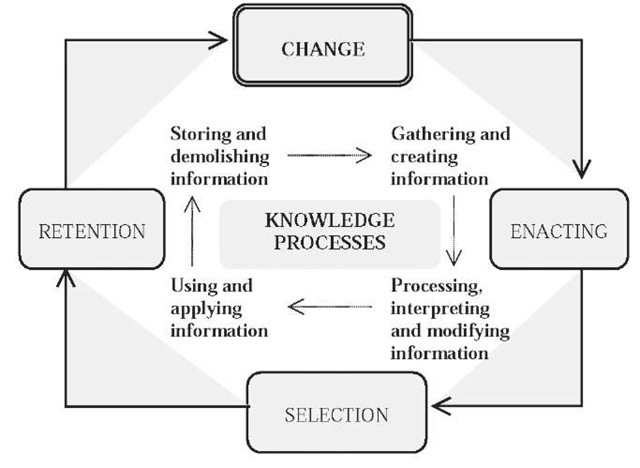

Figure 2. Strategic sense-making and related knowledge process of the organization

Nonaka (1994) considers an organization’s ability to accomplish the task of acquiring, creating, exploiting, and accumulating new knowledge. This formulation takes us very close to how the knowledge process can be operationalized. The knowledge process can be defined as an organizational process in which information is gathered, created, processed, used, and dissolved in order to form an enriched orientation base for taking care of an organization’s basic functions (cf. Gupta et al., 2004, p. 3; Mendes, Gomes, & Batiz-Lazo, 2004, p. 153).

It is important to note that in the actual knowledge process, it is more or less meaningless to make a clear-cut distinction between knowledge and information, for both are processed in such a process. For example, knowledge is not simply extracted from information, for knowledge is possessed by human beings and serves as a background and built-in epistemic frame to deal with complexity, novelty, and the requirements of innovativeness (cf. Wiig, 2000). Thus, genuine aspects of the category of knowledge are in question when we deal with statements, assumptions, and understandings and such learning and communicative processes in which these knowledge assets can be shared, assessed, and enriched. Many theorists consider tacit knowledge in particular as the most challenging and important form of knowledge in organizations (Polanyi, 1966; Nonaka, 1994). It also needs to be stressed that it is not knowledge as something abstract, but a ‘generative dance’ or interplay between (a) knowledge we possess and (b) knowing as an epistemic aspect of the interaction with the world that generates organizational innovation and strategic understanding (Cook & Brown, 1999).

Strategic knowledge processes are those aspects of knowledge processes that have the most profound and far-reaching impact on an organization’s adjustment to contextual changes and on its core competencies. A paradigmatic form of a strategic knowledge process is the sense-making or strategy process in which an organization devotes effort to analyzing its internal attributes and external conditions, and decides on that basis about the action lines in order to achieve its overall goals (cf. Weick, 1995). In such a strategic knowledge process, the organization seeks information on environmental changes and utilizes this in strategy formulation, in which such tools as SWOT analysis have traditionally been used. A basic model of the organizational knowledge-based adaptation process is presented in Figure 2 (Anttiroiko, 2002). This model serves as a heuristic tool to conceptualize knowledge processes. Yet, it is important to keep in mind that this is only a starting point. When taking this idea further, clear-cut sequential stages or phases of the KM lifecycle need to be ‘recontextualized’ as a set of continuous interdependent sub-processes (cf. Mendes et al., 2004, p. 165). Thus, context-related and situational aspects of knowledge need to be integrated with all essential connections to their environments into the key functions and operations of an organization in order to assess their meaning as a part of actual strategic adaptation and sense-making processes.

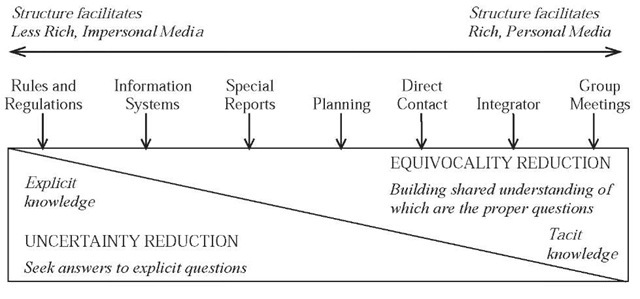

Figure 3. Continuum of knowledge facilitation mechanisms

Applying Daft and Lengel (1986), we may ask how organization structures and systems should be designed in order to meet the need to manage knowledge processes. Well-designed systems help to decrease the uncertainty and ambiguity faced by an organization by ordering the amount of relevant information and by enabling clarification of problems and challenges. Daft and Lengel (1986) propose seven structural mechanisms that can be used to deal with uncertainty and ambiguity in varying degrees, as illustrated in Figure 3. This model resembles the continuum of communication that has explicit knowledge and tacit knowledge as its extremities (Lehaney et al., 2004, p. 21).

The idea is that these mechanisms form a continuum starting from tools to be used to tackle well-defined problems and thus to reduce uncertainty, and proceeding towards more communicative mechanisms designed to facilitate sense-making processes that aim at reducing equivocality or ambiguity (Anttiroiko, 2002).

As stated, a paradigmatic case for strategic knowledge management is the strategy process of an organization (for more on strategy and information resources, see Fletcher, 2003, pp. 82-84). What is of utmost importance is that managers ensure that people feel involved in the strategy formulation process. The staff also needs to understand the meaning of strategy in their own situations. This would help to make strategy documents living guidance owned by all in the organization, as concluded by Wright and Taylor (2003, p. 198).

Another important premise relates to organization culture and work practices that often impede the development of knowledge management. For example, employees may resist a new knowledge management initiative if they perceive it only as extra work. Similarly, employees may be reluctant to share their knowledge if there are no rewards or tangible benefits for themselves or their organizations. In all, the ‘human factor’ is essential for improving KM practices, for most of the positive outcomes are the result of the commitment of all employees, successful structural changes in the organization, and the development of the organizational culture and climate (OECD, 2003, p. 4).

The Role of technology

Information technology (IT) provides a range of tools that can be effectively used in knowledge management. Such applications are sometimes referred to as knowledge technologies. Relevant applications can support decision making, executive functions, planning, communication, and group work. Introduction of new knowledge technologies may be based on a stages of growth model for knowledge management technology, where organizations develop from the person-to-tools strategy, via the person-to-person strategy and the person-to-documents strategy, to the person-to-systems strategy (Gottschalk, 2005).

Tools and technologies available for knowledge management include generic communication tools (e.g., e-mail), blogs, computer-based information and decision support systems, document management systems, wikis, intranets and extranets, groupware, geographic information systems, help-desk technology, and a range of knowledge representation tools (Gupta et al., 2004, pp. 17-24; Grafton & Permaloff, 2003.) In general, the Internet may be suggested as the KM infrastructure due to its widespread availability, open architecture, and developed interfaces (Jennex, 2003, p., 138).

In real life, most of the tools applied in knowledge management are more or less conventional, such as training, seminars, meetings, and the like. Various KM-specific organizational arrangements had been adopted by about half of the organizations studied in the OECD survey on ministries, departments, and agencies of central government in the early 2000s. These measures include central coordination units for KM, quality groups, knowledge networks, and chief knowledge officers. Another important application area is the classification of information, referring to new filing mechanisms, e-archives, and new types of databases. In internal knowledge-sharing, intranet projects form the mainstream, combined with wide access to the Internet and having e-mail addresses for the staff. The external knowledge sharing goes largely hand in hand with the emergence of new practices of e-governance. These practices have increased the knowledge sharing in both local and wider governance processes (OECD, 2003, pp. 17-20; Anttiroiko, 2004).

future trends

The future challenge for public organizations is to increase their responsiveness to stakeholders, especially to citizens. At the same time they need to be capable of strategic institutional mediation in the increasingly turbulent environment, thus bringing an element of continuity and stability to social life, and guaranteeing democratic and civic rights at different institutional levels.

Another trend that may change some premises of strategic knowledge management is the changing nature of media and information landscapes. One indication of this is Web 2.0, which refers to a second-generation of Internet-based services that allow people to collaborate and share information online in new ways (blogs, wikis, ubiquitous technologies, etc.). All this requires increasing capacity to manage knowledge of strategic importance and create innovations of knowledge management (see Montano, 2004).

conclusion

Strategic knowledge management refers to the theory and practice of managing knowledge assets and processes of strategic importance. Public organizations need to create favorable organization structures and environments for knowledge sharing, organizational learning, and other aspects of knowledge management in order to create all the knowledge they require in their adjustment and trend-setting processes.

A main return of strategic knowledge management is better capability to adjust to contextual changes. This is difficult to measure, even if such tools as Balanced Scorecard (BSC), the Intangible Assets Monitor (IAM), and Intellectual Capital Index (ICI) are available. This is because they provide only a partial picture of KM performance, as claimed by Chaudhry (2003, p. 63). What seems to be needed is more process-focused assessments that are able to analyze the steps of KM processes, thus highlighting the actual changes in organizational knowledge base, capacities, and processes. As usual, there is no measurement system that fits all organizations in all situations. Rather, measurement should be tailored to the actual needs of the organization.

KEY TERMS

Intellectual Capital (IC): Knowledge and know-how possessed by an individual or an organization that can be converted into value in markets. Roughly the same as the concept of intangible assets.

Intellectual Capital Management (ICM): A management of value creation through intangible assets. Close to the concept of knowledge management.

Intellectual Property (IP): Any product of the human intellect that is unique and has some value in the marketplace. It may be an idea, composition, invention, method, formula, computer software, or something similar. In practice, special attention is paid to such intellectual property that can be protected by the law (e.g., patent and copyright).

Knowledge Assets (KAs): Statements, assumptions, abstract models, and other forms of knowledge regarding the organization itself and its environment (markets, customers, etc.) that an organization possesses. These assets provide economic or other value to an organization when interacting within it or with its environment.

Knowledge Management (KM): Management theory and practice on managing intellectual capital and knowledge assets, and also the processes that act upon them. In a practical sense KM is about governing the creation, dissemination, and utilization of knowledge in organizations.

Knowledge Management System (KMS): Set of tools and processes used by knowledge workers to identify and transmit knowledge to the knowledge base contained in the organizational memory.

Organizational Learning (OL): An organizational process in which the intentional and unintentional processing of knowledge within a variety of structural arrangements is used to create an enriched knowledge and orientation base, and a better organizational capacity for the purpose of improving organizational action.