Introduction

Information technology (IT) has assumed an important position in the strategic function of the leading companies in the competitive markets (Porter, 2001). Particularly, e-commerce and e-business have been highlighted among IT applications (Porter, 2001). Two basic points of view can be used for understanding IT’s role: the acquisition of a competitive advantage at the value chain, and the creation and enhancement of core competencies (Porter & Millar, 1985; Duhan, Levy, & Powell, 2001).

Several problems have been discussed concerned with IT project results in effectiveness of their management. Effectiveness, in the context of this article, is the measurement of the capacity of the outputs of an information system or of an IT application to fulfill the requirements of the company and to achieve its goals, making this company more competitive (Shimizu, Carvalho, & Laurindo, 2006).

There is a general consensus about the difficulty of finding evidence of returns over the investments in IT (the “productivity paradox”), even though this problem can be satisfactorily explained (Farrell, 2003). Carr (2005) defends the idea that IT in itself has no more strategic value, since it is so widely disseminated that it could not be a source of strategic differentiation anymore.

In order to better use these investments, organizations should evaluate IT effectiveness, which allows the strategic alignment of objectives of implemented IT applications and their results with the company business vision (Shpilberg, Berez, Puryear, & Shah, 2007; Laurindo & Moraes, 2006). Besides, it must be highlighted that if IT applications are associated with changes in business processes, it is possible to notice greater impacts in business performance (Farrell, 2003).

According to Benko and McFarlan (2003), three aspects must be taken into account about IT strategic alignment: IT projects portfolio, business objectives, and the constantly changing situation of business environment.

Thus, the comparison and evaluation of business and IT strategies and between business and IT structures must be a continuous process, since the company situation is constantly changing to meet market realities and dynamics.

Theoretical background

Finding Strategic IT Applications

The discussion about the strategic impact of IT applications started in the 1970s, when technology began to provide more powerful alternatives not only for solving companies’ problems but also for increasing their business competitiveness (Shimizu et al., 2006).

One of the first important proposals for studying the strategic role of IT was that of critical success factors (CSFs), which is still a widespread method used for linking IT applications to business goals, and for planning and prioritizing information systems projects. This method was proposed by Rockart (1979) and states that the information systems, especially executive and management information systems, are based on the current needs of the top executives. These information needs should focus on the CSFs.

Rockart defines CSFs as the areas where satisfactory results “ensure successful competitive performance for the organization.” This author states that CSFs’ prime sources are the structure of the industry, business (or competitive) strategy, industry position, geographic location, environment, and temporal factors.

Basically, the CSF method includes the analysis of the structure of the particular industry and the business strategy, and the goals of the organization and its competitors. This analysis is followed by two or three sessions of interviews with the executives, in order to identify the critical success factors related to business goals, define respective measures (quantitative or qualitative) for the CSFs, and define information systems for controlling CSFs and their measures (Shimizu et al., 2006).

For Rockart, this process can be useful at each level of the company and should be repeated periodically, since CSFs can change through the time and also can differ from one individual executive to another.

The CSF method had an important impact on managerial and strategic planning practices, even though it was primarily conceived for information systems design, especially management and executive information systems.

Besides the utilization in information systems planning and information systems project management, it has been used in strategic planning and strategy implementation, management of change, and as a competitive analysis technique.

Furthermore, the continuous measurement of CSFs allows companies to identify strengths and weaknesses in their core areas, processes, and functions (Rockart, 1979).

More details of the process of implementation of the CSF method can be found in Rockart and Crescenzi (1984).

Understanding IT Strategic Role in companies

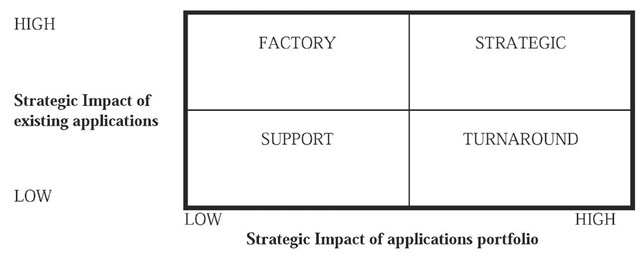

McFarlan (1984) proposed the Strategic Grid that analyzes the impacts of IT-existent applications (present) and of an

applications portfolio (future), defining four boxes, each one representing one possible role for IT in the enterprise: “Support,” “Factory,” “Turnaround,” and “Strategic” (see Figure 1).

• Support: IT has little influence in present and future company strategies.

• Factory: Existent IT applications are important for the company’s operations success, but there is no new strategic IT application planned for the future.

• Turnaround: IT is changing from one situation of little importance (“support” box) to a more important situation in business strategy.

• Strategic: IT is very important in business strategy in the present, and new planned applications will maintain this strategic importance of IT in the future.

In order to assess the strategic impact of IT, McFarlan proposed the analysis of five basic questions about IT applications, related to the competitive forces (Porter, 2008):

Can IT applications:

• build barriers to the entry of new competitors in the industry?

• build switching costs for suppliers?

Figure 1. Strategic grid of impacts of IT applications

• change the basis of competition?

• change the balance of power in supplier relationships?

• create new products?

These questions should be answered considering both present and planned future situations.

Thus, IT may present a smaller or greater importance, according to the kind of company and industry operations. In a traditional manufacturing company, IT supports the operations, since the enterprise would keep on operating even when it could not count on its information systems. However, IT is strategic in a bank for business operations, since it is a source of competitive advantage and a bank cannot operate without its computerized IS.

Nolan and McFarlan (2005) have updated the Strategic Grid, changing the two “axes” for “Need for Reliable IT” (instead of “Present Impact”) and “Need for New IT” (instead of “Future Impact”). These authors stated that companies in “Support” and “Factory” quadrants adopt a defensive approach regarding IT. On the other hand, companies classified in “Turnaround” and “Strategic” quadrants can be considered offensive in IT use. They also indicated the right policies in IT governance (Weil & Ross, 2005) for the board of directors’ use in each of the four situations of the Strategic Grid.

Porter and Miller (1985) highlight the concepts of the value chain (activities inside the company linked by connections and which have one physical component and another of information processing) and value systems (the set of value chains of an industry from the suppliers to the final consumer).

IT permeates the chains of value, changing the way of executing activities of value and also the nature of the connections among them and, therefore, IT can affect competition:

• by changing the structure of the sector since it has the ability to influence each of the five forces of competition (Porter, 2008);

• by creating new competitive advantages, reducing costs, increasing differentiation, and altering the scope of competition scope; and

• by generating completely new business.

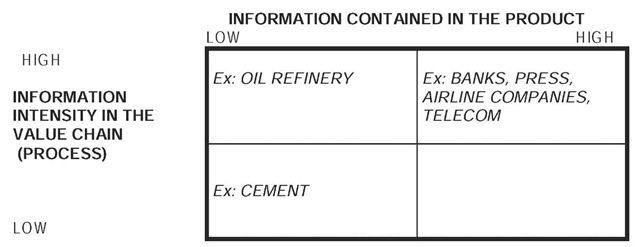

The potential that IT has to make these changes varies according to the characteristics of the process (value chain) and of the product, regarding information needs. The “Information Intensity Matrix” considers the value chain and analyzes “how much” information is contained in the process and the product (see Figure 2). In companies whose products and processes contain a lot of information, information technology will be very important (Porter & Miller, 1985).

Figure 2. Information intensity matrix

In their original article, Porter and Millar did not cite an example for “high information content in the product” or “low information intensity in the process” in the Information Intensity Matrix. However, for Duhan et al. (2001), this would be the case of educational and law firms, for consulting firms would also fit in this same quadrant.

Further according Duhan et al. (2001), an analysis of the value chain would be impaired in the case of knowledge-based companies (such as consulting firms) where it is hard to identify the value that is aggregated to each activity. In these situations, the authors propose that using the essential competencies would be more appropriate to plan the strategic use of information systems.

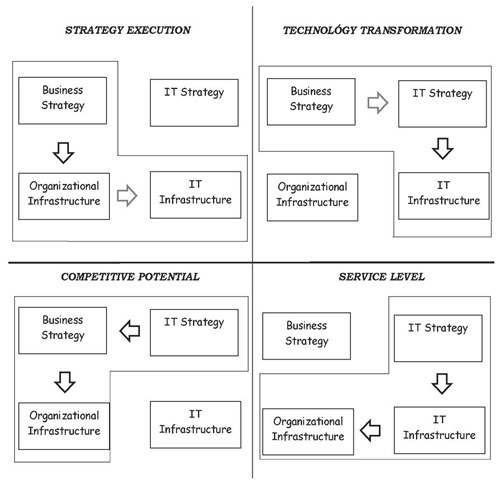

Henderson and Venkatraman (1993) proposed the “Strategic Alignment Model” that analyzes and emphasizes the strategic importance of IT in the enterprises. This model is based on both internal (company) and external (market) factors.

The authors emphasize that strategy should consider both internal and external domains of the company. Internal domain concerns administrative structure of the company; external domain concerns the market and the respective decisions of the company. Thus, according to this model, four factors (that the authors called domains) should be considered for planning IT:

Figure 3. Perspectives of strategic alignment

1. business strategy,

2. IT strategy,

3. organizational infrastructure and processes, and

4. IS infrastructure and processes.

The Strategic Alignment Model brings the premise that the effective management of IT demands a balance among the decisions about those four domains above.

According to Henderson and Venkatraman, there are four main perspectives of Strategic Alignment, through the combination of the four factors, starting from business strategy or from IT strategy, as shown in Figure 3.

One important innovation of this model is that IT strategy could come first and change business strategy, instead of the usually general belief that business strategy comes before IT planning. This planning should be a continuous process, since external factors are in a permanent changing situation. If the company does not follow these changes, it will be in serious disadvantage in the fiercely competitive market. This is particularly true when a new technology is adopted by almost all companies in an industry, passing from a competitive advantage for those that have it to a disadvantage to those that do not use it. Thus, in this sense, the strategic alignment differs from the classic vision of the strategic plan, which does not present the same dynamic approach.

After the proposal of the four perspectives above, Luft-man (1996) described four new perspectives that start in the infrastructure domains, instead of the strategies domains:

• Organizational IT Infrastructure Perspective: Organizational infrastructure ^ IT infrastructure ^ IT strategy

• IT infrastructure Perspective:

IT infrastructure ^ IT strategy ^ Business strategy

• IT Organizational Infrastructure Perspective:

IT infrastructure ^ Organizational infrastructure ^ Business strategy

• Organizational Infrastructure Perspective: Organizational infrastructure ^ Business strategy ^ IT strategy

Luftman (1996) also proposed that in some situations a fusion of two perspectives might occur. In these cases, two perspectives can be simultaneously assessed and impact the same domain: IT Infrastructure Fusion, Organizational Infrastructure Fusion, Business Strategy Fusion, IT Strategy Fusion.

Research has been developed in order to find the enablers of Strategic Alignment. Luftman (2001) listed five of them: senior executive support for IT; IT involved in strategy development; IT understands the business, business-IT partnership; well-prioritized IT projects; and IT demonstrates leadership. The absence or poor performance of these same factors are considered inhibitors of Strategic Alignment.

Some authors, like Ciborra (2004), state the strategic success of IT applications might be achieved through a tentative approach, rather than structured methods of strategic IT planning. These authors argue that frequently the drivers of strategic IT applications are efficiency issues, instead of a result of a strategic IT plan. Some important and well-known successful information systems, with clear strategic impacts, do not present evidence of being previously planned, which seems to be in agreement with this kind of thinking (Eardley, Lewis, Avison, & Powell, 1996).

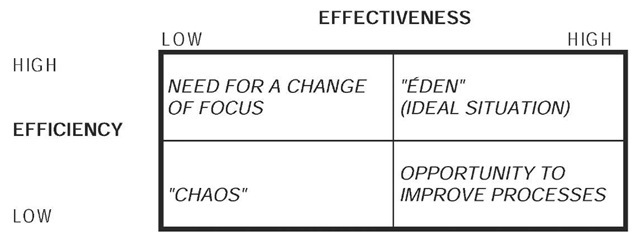

Figure 4. Efficiency vs. effectiveness in IT applications

efficiency and effectiveness: diagnosing the role of it in companies

In this article the importance of focusing on the effectiveness of IT utilization has been emphasized, since frequently analysis is done only from the point of view of efficiency. However, this does not mean that being efficient is not positive; it means that one needs to be efficient in certain areas. In other words, once effectiveness is achieved, increased efficiency can result in important gains and there are many models that help to analyze and improve IT efficiency.

Figure 4 contains a proposed diagram for viewing the situations related to efficiency and effectiveness in the use of IT. When companies demonstrate low efficiency and high effectiveness, they are in “Chaos”—in a critical situation. The first move to get out of this situation should be to aim at increased effectiveness, to align the IT strategy with the business strategy. If the company has low effectiveness, but high efficiency in the use of IT, it means that it should redirect its efforts, change the focus of its activities, in order to use its good capacity where it can add value to the company’s competitiveness. In the case of a company with high effectiveness, but low efficiency in IT utilization, it is necessary to work to improve its processes, with a view to exploiting to the maximum the focus that is already on the right things, and which can contribute to the success of the company’s strategy. Finally, a company that is efficient and effective in the use of IT will arrive in “Eden,” the ideal situation, which should be the goal for all.

conclusion

At present there are a series of applications that have captivated the attention of many and have opened up new possibilities. Both Knowledge Management and Customer Relationship Management have been closely associated to IT. In fact, without IT these concepts could hardly have been effectively used in companies. In this sense, one important example is the growing use of business intelligence applications.

Despite the failure of many virtual enterprises (the so-called “dot.coms”), e-business and e-commerce applications seems to have reached a new maturity level, especially B2B (business-to-business—the connection between companies via the Internet).

There are various success stories, and large companies are increasingly investing in this success. According to Porter (2001), the Internet is the IT tool that, up to the present, has shown the greatest potential of being a source of obtaining or stressing strategic advantages. Therefore, an appropriate analysis and evaluation of IT effectiveness can take on a fundamental role, enabling it to really become a powerful tool for competitiveness.

The concepts described above show the importance of a broad view for analyzing IT strategic alignment. Each of the described models (CSF, Strategic Grid, Information Intensity Matrix, and Strategic Alignment) focuses on specific aspect of this issue.

These widespread known models, in fact, have complementary characteristics, and concomitant use of them allows a better comprehension of the role of IT in an organization.

On the other hand, even the use of the three models does not solve the complexity of IT alignment in organizations. As highlighted by several authors, sometimes a tentative and evolutionary approach can be successfully adopted, in circumstances that structured methods do not work properly. By this continuous focus in the IT strategic alignment, the problems of the “productivity paradox” would be overcome.

Further studies would be necessary for a better and deeper understanding of the importance of IT effectiveness for the success of competitive companies. However, this chapter intended to help find a way for this understanding and to provide some tools.

KEY TERMS

Competitive Forces: According to Porter (2008), the state of the competition in a particular industry depends on five basic forces: new competitors, bargaining power of suppliers, bargaining power of customers, rivalry among current competitors, and substitute products or services.

Critical Success Factor (CSF): One of the areas where satisfactory results “ensure successful competitive performance for the organization,” according to Rockart (1979).

Effectiveness: In the context of IT, the measurement of the capacity of the outputs of an information system or of an IT application to fulfill the requirements of the company and to achieve its goals, making this company more competitive. In other words, effectiveness can be understood as the ability of “do the right thing.”

Productivity Paradox: The discussion about the lack of evidence about the return of investments on IT in the economy productivity indicators.

Strategic Alignment: The IT StrategicAlignment Model was proposed by Henderson and Venkatraman (1993) and consists of a framework for studying IT impacts on business and understanding how these impacts influence IT organization and strategy, as well as how it enables analysis of the market availabilities of new information technologies.

Strategic Grid: Nolan and McFarlan (2005) and Mc-Farlan (1984) proposed the Strategic Grid, which allows the visualization of the relationship between IT strategy and business strategy and operations. This model analyzes the impacts of IT-existent applications (present) and of an applications portfolio (future), defining four boxes, each one representing one possible role for IT in the enterprise: “Support,” “Factory,” “Turnaround,” and “Strategic.”

Value Chain: According to Porter and Millar (1985), the set of technologically and economically distinct activities a company performs in order to do business.