Introduction

Interactive digital television (IDTV), the merging of the Internet and television, has the potential of reaching many consumers. Introducing interactivity in television content will replace lean-backward viewing with a more active lean-forward viewing (Van den Broeck, Pierson, & Pauwels, 2004). This new way of watching TV can have implications for the way people process the advertisements embedded in programmes. We examine the impact of two dimensions of interactivity induced by a TV quiz show, that is, user control and two-way communication (McMillan & Hwang, 2002) on the ad and brand recall of an embedded commercial. User control means the possibility of accessing extra information about the quiz show, the host, and the candidates with the remote control. Two-way communication allows the viewer to play along with the quiz using the remote control.

background

Advertising context Effects

The impact of responses to programme context (e.g., mood, excitement, involvement) on embedded advertisements have been studied extensively (e.g., De Pelsmacker, Geuens, & Anckaert, 2002). This context can have either a stimulating or an inhibiting effect on the processing of an embedded advertisement. Mental processes evoked by the programme have an influence on the processing of the advertisement embedded in the programme. Positive or congruent context effects are caused by the “carry-over” principle of the programme-induced attention, liking, interest, or arousal toward the advertisement that follows (Moorman, Neijens, & Smit, 2005). Negative or contrasting relationships have been explained by the cognitive absorption of the programme, leaving less cognitive abilities for processing the advertisement (Lang, 2000).

Interactivity and Information processing

Interactivity can be defined in different ways. Wu (2005) distinguishes between actual or feature-based interactivity and perceived interactivity. McMillan and Hwang (2002) define three underlying dimensions of interactivity: two-way communication, user control, and time delay.

A considerable amount of empirical studies have investigated the effects of the interactivity of a message vehicle on an individual’s cognitive information processing in an Internet context. Some studies found a positive impact of interactivity on memory (Chung & Xinshu, 2004; Macias, 2003), while others found no impact or even a negative impact (Bezijan-Avery, Calder, & Iacobucci, 1998). The cognitive load theory (CLT; Van Merrienboer & Sweller, 2005) can be used to explain both. The CLT assumes that the human working memory is limited in processing novel information. There are broadly two types of cognitive load that can affect the working memory (Van Merrienboer & Sweller): intrinsic cognitive load, which is related to the intrinsic nature of the information (in this study the questions and answers of the quiz programme, and the content of the additional programme information), and extraneous cognitive load, which corresponds to the mental effort imposed by the way the information is presented (for instance, in this study, programme interactivity). According to the elaboration likelihood model (Petty & Cacioppo, 1981), extensive information processing only occurs when the consumer is motivated to process the information. When this prerequisite is accomplished, he or she must also have the ability (cognitive capacity) to do so. The amount of interactivity can have an influence on both mechanisms. Interactivity can increase involvement with the content (Fortin & Dholakia, 2005), which increases the motivation to process the information. However, following the CLT, interactivity can also increase the total cognitive load, and thus diminishes the ability to process information. Therefore, depending on the strength of the intrinsic cognitive load, the individual will or will not have enough ability to process the information (the interactive programme), which will further influence the processing of the embedded advertisement.

In this study, we investigate the context effects of two dimensions of programme interactivity representing a low level of intrinsic load (user control regarding information about the programme, candidates, host) and a high level of intrinsic load (two-way communication involving the questions and answers in the quiz) on ad and brand recall.

user control

User control is “the range of ways to manipulate the content” (Coyle & Thorson, 2002) and refers to the amount of possible interactions the user has to get the information in the order and pace he prefers (in this study the amount of hyperlinks in the additional programme information). Different levels of this user-control dimension could influence the motivation to process the programme. Because the intrinsic load (extra programme information) is low, we do not expect that the additional load imposed by the interactivity (user control) will lead to limited information processing capacity. Although the respondents have the ability to process the programme and the embedded advertisement when the programme has no user control, the involvement with the programme and thus the motivation to process it will be relatively low. This low processing motivation is expected to be transferred to the advertisement, leading to a superficial processing of the advertisement. At a moderate level of user control and no two way, the motivation to process the information and programme involvement increase, thus facilitating the processing of the programme. This attentive state is expected to be transferred to the subsequent advertisement. A high level of user control will increase the motivation to process the programme but, given the relatively low intrinsic cognitive load of the user control process, this motivation to process information may be higher than is required. This may lead to the development of negative thoughts, which may inhibit advertising processing. Also, more clicks lead to less information per click. This decrease in information complexity may also lead to the development of feelings of boredom and irritation. We expect the following.

H1: A moderate level of user control will lead to a higher ad and brand recall than a low or a high level of user control.

Two-Way communication

This dimension of interactivity can be characterized as a mutual discourse or the capability of providing feedback (Ha & James, 1998). In this study, two-way communication is manipulated through the possibility of playing along with a quiz show. This implies that the interactivity leads to a high intrinsic load as a result of answering the quiz questions (multiple choices) on screen using the remote control. Although the individual may have a high motivation to process the programme when playing along, he or she may lack the ability to do so given the linear time flow of the programme, which demands the working memory to process the information very fast. This limited cognitive capacity to process the programme may lead to a cognitive capacity problem when the individual is exposed to the embedded advertisement. We expect the following.

H2: Programme embedded two-way communication (playing along) will lead to a lower ad and brand recall than no two-way communication (notplaying along).

Interaction Effect between user control and Two-Way communication

It is unclear what the combined effect of two-way communication and user control in the program context will be on the recall of the embedded ad and brand. On the one hand, a combination of playing along and the availability of more user control could result in a higher cognitive load and less recall of the embedded ad. Following this argument, a combination of low user control and no two-way communication should lead to the highest recall, and high user control combined with two-way communication (playing along) to the lowest. On the other hand, when the viewer cannot play along with the quiz and has no user control, his or her motivation to process the programme will be low, and consequently also the motivation to process the ad. Earlier we also hypothesized that a moderate level of user control leads to the most optimal cognitive activation state to process the programme. This activation state will be transferred to the ad when the consumer has the ability to process the ad in depth. When the consumer does not play along with the game, he or she will have sufficient cognitive resources to process the programme, and thus we could expect that this combination of a moderate level of user control and two-way communication will lead to a positive effect on ad and brand recall. Given that playing along with the quiz absorbs a lot of cognitive resources, the additional cognitive load induced by the moderate level of user control, might lead to a limited capacity problem. Since the combined effect of user control and two-way communication is not clear, we formulate the following open research question.

Q1: What is the interaction effect of user control and two-way communication on ad and brand recall?

empirical study

Research Method

The hypotheses and research question were tested by means of a 3×2 (level of user control x level of two-way communication) between-participant experimental design. The programme context was an old episode of a well-known Belgian quiz show. User control was manipulated in the programme through the amount of clicks in the additional transparent information overlays that appeared automatically on screen during the sequence of the programme and that could be accessed by means of the remote control. Additional information about the host, candidates, quiz rules, and prizes was provided. The first level of user control did not enable any interactivity. Instead, the viewer got the extra programme information on paper. At the second level, a moderate amount of clicks (five clicks) was available during two moments in the programme. In the highest user-control condition, 26 clicks during four moments in the programme were available. The amount of information was kept constant across conditions. Two-way communication was varied on two levels. In the playing-along condition, for each question in the quiz, the viewer had the opportunity to make a choice out of three multiple choice answers using the remote control. In the not-playing condition, no interactivity was made possible. The advertisement and brand embedded in the program were unknown in Belgium at the time of the study to avoid confounding effects of existing knowledge and/or experience. We used a toothpaste advertisement from The Netherlands.

A sampling frame of 521 Flemish individuals was randomly selected by an Internet research company, taking age, gender, and education quota into account to be representative of the Belgian population. A net sample of 246 persons participated in the study. The average age of the participants was 38 years (range 21-56 years, 50% between 21-40 years old ), 61.8% were males, 44.7% held a high school diploma, and 55.3% finished a higher education level.

The participants were individually invited to an experimental living-room setting. The participants were told that they were participating in a test viewing of an IDTV application. They were randomly assigned to one of the six experimental conditions. The participants viewed 15 minutes of the TV quiz show with an advertising break in the middle of the programme, after which they entered a computer-assisted questionnaire containing, amongst others, the recall measures. The experiment lasted 30 minutes in total. Each respondent received an incentive of €25

Advertisement recall was measured using 10 multiple-choice statements about content aspects of the advertisement (true vs. false). The scores were calculated by counting the number of correct answers (score between 0 and 10). Unaided brand recall was measured at two moments: immediately after the experiment and 10 days after the experiment. Of the 246 respondents, 168 cooperated in the delayed brand recall test (response rate of 68%).

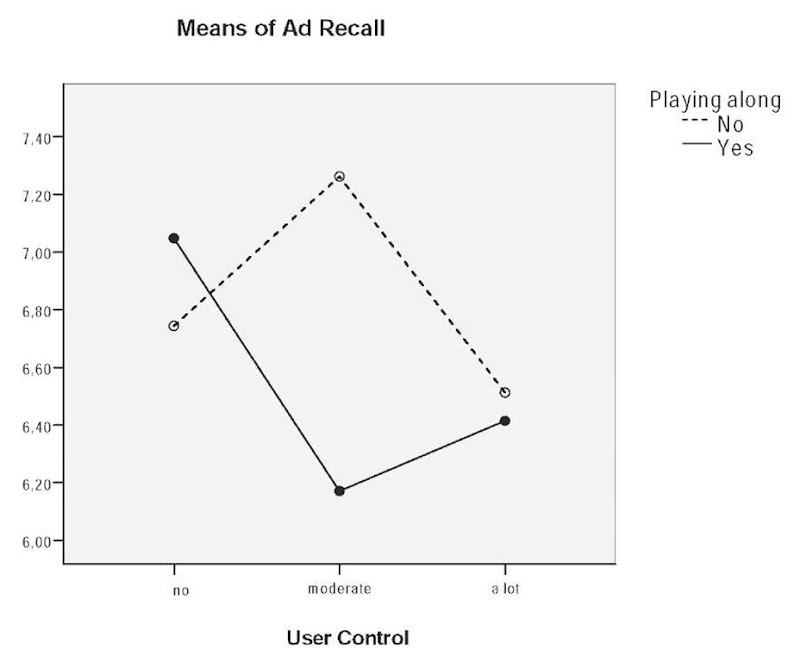

Figure 1. Interaction effect of user control and two-way communication on advertisement recall

Results

Advertising recall was measured as a score on a 10-point scale, and thus it was a ratio-scaled variable. The data met the conditions for parametric analysis. The ANOVA (analysis of variance) results indicate that user control (p=.046) has a significant main effect on ad recall. However, unexpectedly, the significance of this factor was driven by the difference between no user control (M=6.90) and high user control (M=6.46; t=2.661; p=.009), and not between the moderate level (M=6.71) vs. the high (t=1.390; p=.167) and low level (t=.957; p=.341), as expected. User control had no significant effect on brand recall measured immediately after the experiment (no=34.6%, moderate=36.1%, high=32.9%; Chi2=.189; p=.910) or on delayed brand recall (no=28.8%, moderate=25.0%, high=27.7%; Chi2=.971; p=.896). H1 is not supported.

Two-way communication also has a significant negative effect on ad recall (p=.038). Not playing along with the quiz resulted in a higher ad recall (M=6.84) than playing along (M=6.55, t=2.011; p=.045). As expected, two-way communication also had a significant negative effect on brand recall measured immediately after the experiment (40.2% vs. 29%; Chi2=3.370; p=.066). This difference became even more significant after a delay of 10 days (36.7% vs. 18.1%; Chi2=7.992; p=.008). H2 is accepted.

In Figure 1, the significant interaction effect between user control and two-way communication (p<.001) is shown. A moderate level of user control results in the highest ad recall rate when there is no play-along possibility (M=7.26) than when the consumer could play along. The lowest ad recall rate across all conditions results from the combination of a moderate level of user control and playing along (M= 6.17). This difference was significant (t= 4.085; p<.001). When there was no user control embedded in the programme, playing along had no effect on ad recall (M= 6.74 vs. M= 7.05; t= -1.315; p=.192). Also, when the level of user control was high, there appeared to be no difference in ad recall as a result of playing along or not (M=6.51 vs. M=6.42; t= .416; p=.679). The same interaction effect of user control and two-way communication was noticeable on immediate and delayed brand recall.

future trends

Interactivity is assumed to be the major difference between new and traditional media. With IDTV, the viewer or user can interact with the TV content using the remote control, providing him or her with more control over the viewing experience (Van den Broeck, 2004). Requesting additional information about actors in a TV soap, participating in TV talk shows through on-screen chatting, and requesting a coupon in an advertisement are a few of the new possibilities made possible by this medium. This hypermultimedia content changes the way people watch TV, and thus can have implications on the way advertisements are perceived and processed.

The results of this study have implications for broadcasters, media planners, and advertisers. For broadcasters, the IDTV technology may increase the effectiveness of advertising in terms of ad and brand recall compared to traditional TV. The challenge for broadcasters is to reach enough viewers for their live interactive programming. Once this is achieved, our results demonstrate that IDTV compared to traditional TV can increase the brand recall up to 5.6% (difference between brand recall in the condition of no user control and no play-along possibility, and the condition with a moderate level of user control with no play-along possibility; 41% vs. 46.6%). For media planners and advertisers, the results may be of interest when the advertising goal of the campaign is to increase the awareness of the ad message or the brand. Placing an advertisement in an interactive programme might enhance ad and brand recall if the programme has a moderate level of interactivity. Too little programme interactivity might lead to boredom and to negative advertising results, whereas too much interactivity might load the respondent’s cognitive abilities so much that he or she will no longer pay attention to the advertisements that appear during the commercial break. To achieve the most optimal recall results, programme interactivity should increase the motivation of the viewers to watch the content more in depth without overloading them. Therefore, a moderate level of user control without two-way communication would lead to the best results.

Further research should investigate the effects of less-cognitive-demanding two-way communication applications than the one used in this study. Perhaps imposing fewer questions on the viewers and giving them more time to respond might lead to this optimal IDTV experience for broadcasters and advertisers. In this study, we investigated memory-related aspects of processing the advertisement. Investigating the impact of programme interactivity on ad and brand attitudes would also be interesting. Further research is also warranted to study more in depth the effects of interactivity on memory and attitudes after a time delay. The results of the current study should be tested in a real-time (live) setting to corroborate the findings of this experimental context. Finally, research in larger samples is needed to reliably assess the differences in effects between different groups of viewers (e.g., by gender, age, education, etc.).

conclusion

Both programme-induced user control and two-way communication had an influence on recall. However, the effect of user control was less outspoken than that of two-way communication. User control did not have a significant main effect on brand recall, and only had a weak negative effect on ad recall. Two-way communication (playing along with the TV quiz show) did have a strong and significantly negative impact on both immediate and delayed brand recall and on ad recall. The high motivation to process the quiz when playing along in combination with the high intrinsic load of the questions and answers apparently left little cognitive resources to process the embedded advertisement. The highest recall is obtained as a result of a moderate level of user control and playing along. In this condition apparently the viewer has both the ability and the motivation to process the programme, a processing state which is transferred to the embedded ad.

Besides the difference in cognitive intrinsic load, the fact that two-way communication is more likely to imply a limited-capacity problem compared to user control may also be explained by the fact that user control is a more voluntary interaction in terms of the time spent in the interactive information and the order in which viewers access the information. On the contrary, when playing along, the viewer has to follow the sequence and the order of the questions presented in the quiz programme. Past studies also found that time pressure increases the likelihood for cognitive overload to occur.

KEY TERMS

Carry-Over Advertising Context Effect: It is when psychological reactions evoked by a programme do not immediately disappear when the programme is interrupted by a commercial break, but have an influence on the processing of the advertisement embedded in the programme

Cognitive Overload: This occurs when the volume of information supply exceeds the information processing capacity of the individual.

Extrinsic Load: It is the cognitive load that is related to the representation of the information (form, style, etc.).

Interactive Digital Television (IDTV): IDTV is the merging of the Internet and television.

Intrinsic Load: It is the cognitive load that is related to the information content itself.

Two-Way Communication: It refers to mutual discourse, the capability of providing feedback, or the exchange of roles.

User Control: It is the range of ways to manipulate the content.