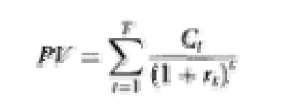

Discounted cash flow (DCF) models are used t o determine the present value (PV) of an asset by discounting all future incremental cash flows, C,, pertaining to the asset at the appropriate discount rate r,:

Present value analysis (originating from Irving Fisher (1930) using DCF models is widely used in the process of deciding how the company’s resources should be committed across its lines of businesses, i.e. in the appraisal of projects. The typical application of a DCF model is the calculation of an investment’s net present value (NPV), obtained by deducting the initial cash outflow from the present value. An investment with positive NPV is considered profitable. The NPV rule is often heralded as the superior investment decision criterion (see Brealey and Myers, 1991). Since present values are additive, the DCF methodology is quite general and can be used to value complex assets as well. Miller and Modigliani, in their highly influential 1961 article, note that the D CF approach can ”be applied to the firm as a whole which may be thought of in this context as simply a large, composite machine.” They continue by using different DCF models fo r valuation of shares in order to show the irrelevance of dividend policy. The DCF approach is also the standard way of valuing fixed income securities, e.g. bonds and preferred stocks (Myers, 1984).

Option-pricing models can in a sense be viewed as another subfamily of DCF models, since the option value may be interpreted as the present value of the estimated future cash flows generated by the option. Since the estimation procedures for options’ future cash flows are derived from a specific and mathematically more advanced theory (introduced for finance purposes by Black and Scholes (1973)), option-pricing theory is usually treated separately from other types of DCF modeling.

Myers (1984) identifies four basic problems in applying a DCF model to a project: (1) estimating the discount rate; (2) estimating the project’s future cash flows; (3) estimating the project’s impact on the firm’s other assets’ cash flows; and (4) estimating the project’s impact on the firm’s future investment opportunities.

When estimating the discount rate one must bear in mind that any future cash flow, be it from a firm, from an investment project or from any asset, is more or less uncertain and hence always involves risk. It is often recommended to adjust for this by choosing a discount rate that reflects the risk and discounting the expected future cash flows. A popular model for estimating the appropriate risk-adjusted discount rate, i.e. the cost of capital, is the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) by Sharpe (1964), where the discount rate is determined by adding a risk premium to the risk-free interest rate. The risk premium is calculated by multiplying the asset’s sensitivity to general market movements (its beta) to the market risk premium. However, the empirical validity of CAPM is a matter of debate. Proposed alternatives to the single-factor CAPM include different multifactor approaches based on Ross’s arbitrage pricing model (Ross, 1977). Fama and French (1993) identify five common risk factors in returns on stocks and bonds that can be used for estimating the cost of capital.

Different procedures for estimating future cash flows are normally required, depending on which type of asset is being valued. The Copeland et al. (1994) DCF model for equity valuation provides a practical way of determining the relevant cash flows in company valuation. By forecasting a number of financial ratios and economic variables, the company’s future balance sheets and income statements are predicted. From these predictions, the expected free cash flows (i.e. cash not retained and reinvested in the business) for future years are calculated. The sum of the discounted free cash flows for all coming years is the company’s asset value, from which the present market value of debts is deducted to arrive at a valuation of the equity.

Irrespective of asset type, cash flows should normally be calculated on an after-tax basis and with a treatment of inflation that is consistent with the discount rate, i.e. a nominal discount rate requires cash flows in nominal terms (Brealey and Myers, 1991). It is also important to ensure that all cash flow effects are brought into the model – including effects on cash flows from other assets influenced by the investment.

An intelligent application of DCF should also include an estimation of the impact of today’s investments on future investment opportunities. One example is valuation of equity in companies with significant growth opportunities. The growth opportunities can be viewed as a portfolio of options for the company to invest in second-stage, and even later stage projects. Also research and development and other intangible assets can, to a large part, be viewed as options (Myers, 1984). Another example concerns the irreversible character of many capital investments. When the investment itself can be postponed, there is an option to wait for more (and better) information. Ideas such as these are exploited in Dixit and Pindyck (1994), where it is shown how the complete asset value, including the value from these different types of opportunities, can be calculated using option-pricing techniques or dynamic programming.