(1928-1997) American Astrogeologist

In 1994, the proponents of potential extraterrestrial impacts with the Earth having caused mass destruction and many of the great extinction events were given a great piece of support when the Shoemaker-Levy 9 comet was observed break- ing up and crashing to the surface of Jupiter. The damage was obviously intense and visible scars remain today. That event also made the name of Shoemaker world famous. Eugene Shoemaker, his wife Carolyn Shoemaker, and David Levy had been involved in a decade-long study to identify Earth-crossing asteroids and comets when they made the discovery. Although it came a year after his retirement, the discovery and fame served as a culmination of a 45-year career with the U.S. Geological Survey in which he founded a new branch with the title of astrogeology.

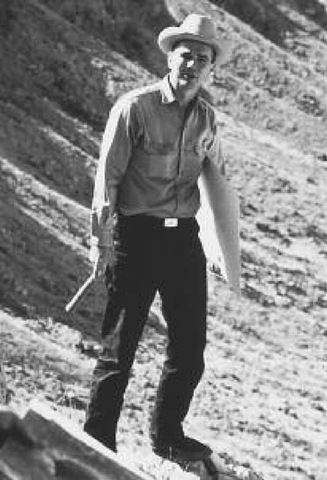

Eugene Shoemaker leads a field trip to Meteor Crater, Arizona, in 1967

Eugene Merle Shoemaker was born in 1928 in Los Angeles, California. The family soon moved to Buffalo, New York, where he was quickly recognized as a prodigy. He skipped grades and attended extracurricular classes. He became interested in geology at the Buffalo Museum of Science. The family returned to Los Angeles, where Shoemaker entered California Institute of Technology at 16. He received a B.S. degree in 1947 and an M.S. in 1948. He joined the U.S. Geological Survey as a research assistant that year.

Although he did not start out his career in extraterrestrial studies but rather field mapping and searching for uranium deposits in the Colorado Plateau, he soon became interested in cratering around nuclear explosions. This work led him to question the origin of Meteor Crater in Arizona. In that classic work, he defined the structures and features that would be observable in any impact crater. He earned his Ph.D. from Princeton University, New Jersey, in geology in 1960 based on this work. It also began Shoemaker’s fascination with impact craters which drove the rest of his career. This enthusiasm and some prodding convinced NASA to sponsor a lunar geology program that he directed. In this program Shoemaker demonstrated that the surface of a planet could be dated by counting the number of craters and assuming a certain level of influx. This work was carried out using telescopes but in truth, Shoemaker wanted to be an astronaut. Unfortunately, he was diagnosed with Addison’s disease in 1962 and was unable to achieve this dream. He had to be satisfied serving as acting director of NASA’s Manned Space Sciences Division and helping to design missions and train astronauts.

Shoemaker worked extensively on the Apollo 11, 12, and 13 missions and became quite a celebrity. Any expert information about lunar geology on television usually came from him. He was world famous then as well. However, the high-profile public lifestyle was physically and emotionally taxing and as a result he turned toward teaching. He taught part-time at California Institute of Technology from 1962 to 1985 and even served as chair for the Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences from 1969 to 1972. He also worked on Project Voyager with Larry Soderblom. In 1982, Shoemaker began a 15-year period of work at the U.S. Geological Survey, Flagstaff office, where he made regular excursions to the Palomar Observatory and occasional trips to Australia to observe comets and asteroids that could collide with Earth. The 1997 National Geographic special, “Asteroids’ Deadly Impact,” prominently featured his work. He was famous yet again.

On one such comet and asteroid observation trip to Australia, Gene Shoemaker was killed in an automobile accident on July 18, 1997. Gene had a wish granted posthumously when on January 6, 1998, a small capsule containing one ounce of his cremated remains was transported to the Moon aboard NASA’s Lunar Prospector spacecraft. He finally made it to the Moon.

Gene received a number of prestigious awards throughout his distinguished career, including the NASA Medal for Scientific Achievement in 1967, membership in the National Academy of the Sciences in 1980, Geological Society of America’s Arthur L. Day Medal in 1982, and Geological Society of America’s G. K. Gilbert Award in 1983, as well as being elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1993. His greatest tribute, however, was being awarded the United States National Medal of Science in 1992. It is the highest scientific honor and is bestowed by the president of the United States.