Cointelpro, FBI-speak for Counterintelligence Program, was the bureaucratic designation for the FBI’s clandestine and illegal program of political repression directed against dissenters from the 1950s to the 1970s. The most dangerous manifestation of J. Edgar Hoover’s countersubversive and antidemocratic ideology during his fifty-year reign as director of the FBI, cointelpro was designed “to divide, conquer, weaken” and otherwise disrupt a wide variety of social movements through the use of intimidation, surveillance, and “dirty tricks.” Thousands of individual cointelpros were carried out under several general headings: Espionage; Communist Party (CPUSA); Socialist Workers Party (SWP); Disruption of White Hate Groups; New Left; and Black Extremists. However, in its common usage, the term “cointelpro” has come to signify the entire context of secret counterrevolutionary action directed against the social-democratic and civil rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s. When activists and congressional investigators exposed the actions of cointelpro in the 1970s, it publicly revealed just how closely the FBI resembled a totalitarian political police and sparked the most significant backlash against the Bureau in its history.

Development of Repressive Techniques

The formation of cointelpro represents a consolidation and expansion of the federal government’s repressive apparatus, most of which had been in place since the FBI’s founding in the early 1920s. The innovation of cointelpro in the 1950s over its predecessor cominfil (Communist Infiltration Program) was the FBI’s turn to active disruption rather than mere infiltration and harassment of dissident groups. To this end, the Bureau developed a standard repertoire of techniques.

Cointelpro made careful use of “a cooperative news media” to “leak” disinformation about political groups. Agents engaged in basic acts of sabotage such as canceling meetings, disrupting speaking engagements, and interfering with party fund-raising. cointelpro compiled and shared blacklist information with employers and landlords. cointelpro made harassment arrests designed not to convict activists for criminal violations, but to isolate leaders like black activist Angela Davis and force their supporters to refocus the movement’s financial and political resources into legal defenses. When prosecutions occurred, cointelpro fabricated evidence, extorted testimony, and covered up possibly exculpatory evidence. Such judicial abuses of the FBI’s investigative capacity were rampant during the trial of the Chicago 7 in the late 1960s.

Inducing “paranoia” in targeted political groups was a stated goal of cointelpro, as revealed in one FBI document that unequivocally states its desire to “enhance the paranoia endemic in [New Left] circles, and will further serve to get the point across that there is an FBI agent behind every mailbox” (Churchill and Vander Wall, 1990b). To this end, cointelpro employed both simple forms of surveillance such as warrantless wiretaps and electronic bugging, as well as more invasive forms such as break-ins, known as “black-bag jobs,” human tails, and mail opening. cointelpro ran an enormous domestic spy-ring composed of thousands of informants, infiltrators, and agents provocateurs. Paid by the Bureau to join political groups, these infiltrators either provided inside information or provoked members into committing radical acts that could be used to generate bad publicity or to justify police crackdowns. cointelpro sent bogus letters and fake flyers, known as “black propaganda,” designed to create personal splits, exacerbate political factionalism, or pit competing groups against one another. A particularly insidious form of black propaganda was known as “snitch-jacketing,” in which the Bureau worked to cast suspicion on targeted individuals for being a spy or Bureau informant with the intention of isolating or provoking reprisals against the target by his or her former comrades. These forms of black propaganda proved especially effective at weakening both the Communist Party (CPUSA) and the Black Panther Party (BPP). At its most extreme, cointelpro has been—rarely but nonetheless directly—involved in assassinations, including the murders of Chicago BPP leader Fred Hampton and American Indian Movement (AIM) member Anna Mae Aquash.

In the end, the secrecy surrounding cointelpro may speak the loudest: all of these techniques are either illegal or were widely abused and represent the structured and systematic violation of the civil liberties of citizens engaging in constitutionally protected activities.

A History of Abuses

According to FBI documents made public in the mid-1970s, the first directives to carry the cointelpro heading were issued in 1956 and targeted what was left of the CPUSA. In the total of 1,388 coin-telpro actions implemented against the CPUSA between 1956 and 1971, nearly all of the tactics outlined above were developed and “field-tested,” pitting the vast resources of Hoover’s political police against an already moribund Communist group. Despite its weakness as an organization, the CPUSA was targeted by the most colorful and potentially murderous cointelpro of all time under the name “Operation Hoodwink.” The operation was approved in October 1966 and maintained for several years, during which the FBI sent forged letters and leaflets with the aim of provoking a fight between the CPUSA and the Cosa Nostra over labor issues in the Brooklyn dockyards. The obvious intention of Operation Hoodwink was to encourage mob leaders to “neutralize” key CPUSA members, but while there is no evidence that any Communists were “rubbed out” as a result, it is not for lack of trying by the FBI.

The first extension of cointelpro beyond the surviving “Old Left” came in the early 1960s, when the FBI began actions against the Puerto Rican Independence Movement and the southern-based civil rights movement, especially its leader Martin Luther King, Jr. In the words of a published coin-telpro document, “the Bureau wishes to disrupt the activities of these organizations and is not interested in mere harassment” (Churchill and Vander Wall, 1990b).

Hoover’s commitment to white supremacy has been well documented, and he took a direct interest in the FBI’s campaign to disrupt the civil rights movement, which he regarded as nothing less than a Communist conspiracy. Hoover held a personal vendetta against King, whom he repeatedly referred to as a “burrhead” possessed by “obsessive degenerate sexual urges.” When King publicly accused Hoover of refusing to protect civil rights activists from violence, Hoover attacked King as “the most notorious liar in the country.” Hoover placed King under full-time surveillance, infiltrated the Southern Christian Leadership Council (SCLC), unleashed a public smear campaign, and even went so far as to try to blackmail King into committing suicide. Such evidence substantiates King’s claim that “they are out to get me, to harass me, break my spirit” (Garrow). Today, King’s family continues to cite Hoover’s campaign against the civil rights leader as circumstantial evidence of Bureau involvement in King’s assassination.

The project code-named “cointelpro-White Hate Groups,” involving the infiltration of the southern Ku Klux Klan during the 1950s and 1960s, further reveals the racist and reactionary goals of the Bureau during the upheavals of those decades. Despite the fact that the Bureau claimed to have over 2,000 informants in the Klan, roughly equal to 20 percent of the total KKK membership across the South in 1965—including a significant portion of Klan leadership—the FBI was unwilling and supposedly unable to prevent Klan violence against civil rights activists. Instead of investigating the murders of at least thirty-five civil rights workers, the Bureau actively harassed and investigated the victims, who they believed, in the words of one Klan leader and FBI informant, represented a “nigger-commie invasion.” Eventually, the Bureau did make some progress in disrupting the Klan, but only after the civil rights movement had achieved significant legislative victories in 1964 and 1965.

As the southern civil rights movement gave birth to a wide range of social-democratic, civil rights, and national liberation struggles—including Black Power organizations like the BPP, indigenous groups like the AIM, the student New Left, and the feminist movement—cointelpro grew more aggressive under the combined forces of Hoover and Nixon.

The FBI document that inaugurated the project headed “cointelpro: Black Nationalist-Hate Groups” clearly expresses its intentions: “The purpose of this new counterintelligence endeavor is to disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of black nationalist, hate-type organizations and groupings, their leaders, spokesmen, membership, and supporters” (Churchill and Van-der Wall, 1990b). The FBI’s covert war on the BPP began with the extensive infiltration of the Panthers by informers and provocateurs. cointelpro had great success with “snitch-jacket” campaigns against Stokey Carmichael, Eldridge Cleaver (who fled the country), and Geronimo Pratt (who was successfully framed for a murder that the FBI’s own surveillance later exonerated him of after he spent over twenty-five years in prison). Forged cartoons and flyers sent by the FBI to spark fights between the BPP and another group known as United Slaves resulted in the deaths by shooting of Panthers Jon Huggins and Bunchy Carter in 1969. Most violently of all, the FBI engineered the assassination of Fred Hampton and BPP Field Marshal George Jackson in San Quentin prison in 1971. Following Hoover’s explicit directive to “prevent the rise of another black ‘messiah,’” the nineteen-year-old Hampton was targeted because of his amazing success at transforming Chicago street gang members into community activists. Based entirely on evidence provided by an FBI informant, the Chicago police raided Hampton’s house early on the morning of 4 December 1969, killing both Hampton and fellow Panther Marc Clark as they slept in their beds, injuring several others, and arresting all the survivors for assaulting the police. Though these murders were officially declared “justifiable” at the time, a 1983 judgment determined that there had been an active government “conspiracy to deny Hampton, Clark, and the BPP plaintiffs their civil rights” (Churchill and Vander Wall, 1990b).

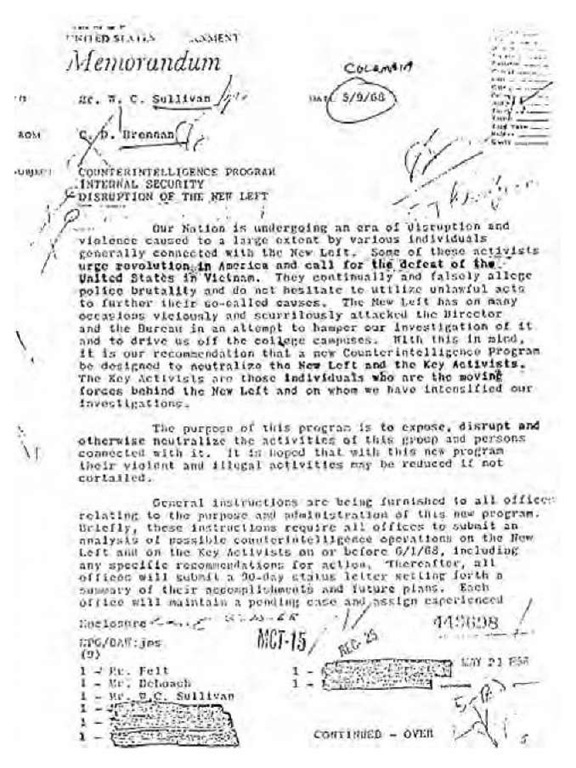

Memo from C. D. Brennan to W. C. Sullivan, 9 May 1968.

The highest concentration of cointelpro actions were directed against members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) in the early 1970s. The AIM sought to restore pride in traditional Indian culture, to confront white America with its denied history of genocide against indigenous people, and to fight for their collective rights as sovereign nations. The FBI’s campaign began after the AIM seriously embarrassed the Nixon administration in the highly publicized takeovers of Alcatraz Island in 1969 and the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1972. After the AIM shifted its organizational focus back to the reservation, leading to the second siege of Wounded Knee in 1973, the FBI began a bloody struggle to disrupt and destroy the group. In the end, dozens of AIM activists were killed and imprisoned, and Leonard Peltier was successfully convicted for the murder of two FBI agents based on forged evidence, extorted testimony, an illegal extradition from Canada, and judicial intimidation.

Beginning shortly after the student takeover of Columbia University in 1968, the “cointelpro-New Left” project targeted the full range of student and anti-Vietnam protest groups, including Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), Vietnam Veterans Against the War, the Weathermen, and several feminist groups, both radical and mainstream. Movement leaders, including all members of the Chicago 7, were explicitly targeted by coin-telpro as well as pediatrician Benjamin Spock, Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, feminist leader Betty Friedan, and even Beatles member John Lennon. Special efforts were made to prevent cross-racial coalitions, especially an alliance between SDS, the Weathermen, and the BPP. Provocateurs played a key role in disrupting the New Left. The most famous New Left provocateur was known as “Tommy the Traveler” (Thomas Tongyai), who was paid by the FBI to move from college to college in upstate New York posing as a radical member of SDS and encouraging students to kill cops and blow up buildings. When a group of students actually took his advice and destroyed the ROTC office at Hobart College, Tommy’s cover was blown. Hundreds of similar cases have been documented on campuses across the country in the 1960s. In the end, cointelpro proved quite effective at distorting the message and public image of New Left groups, hastening their fragmentation, accentuating their suspicious-ness, and facilitating their decline.

However, the New Left finally gave cointelpro is comeuppance. The existence of cointelpro remained an official secret until 8 March 1971, when a group of activists calling itself the Citizens Commission to Investigate the FBI broke into the FBI’s office in Media, Pennsylvania, and “liberated” a large number of files. When the group published several of these documents with the cointelpro heading, Hoover immediately discontinued the program to prevent “embarrassment to the Bureau.” After Hoover’s death, the Church Committee began a major investigation of the FBI. Aided by the passage of the Freedom of Information Act, the American people have now gained a fuller picture of the FBI’s history and its role as a political police. Indeed, the extent of cointelpro activity is still being exposed, as evidenced by the recent revelation of FBI infiltration of the women’s movement. As one columnist for the Washington Post explained in the mid-1970s after the revelations of cointelpro and similar lawlessness by the CIA, “American society has gone buggy on conspiracy theories of late because so many nasty demonstrations of the real thing have turned up” (Don-ner). Despite the significant exposures, the major media and congressional investigators chose to blame FBI “abuses” on the “excesses” of the recently deceased Hoover, and, in the end, no substantial reforms or checks were instituted.

Although the FBI officially terminated cointel-pro in the 1970s, scholars and activists have argued that the FBI continues its practice of spying on and disrupting social-democratic and civil rights organizations, including antinuclear and Third-World solidarity groups in the 1980s, radical environmentalist organizations in the 1990s, and the current global justice movement.