Overview

Although great believers in the Slave Power Conspiracy and often party to anti-Catholic and other evangelically oriented conspiracy theories themselves, American abolitionists were also frequently accused of conspiracy, especially in the South but also in the North. Improbable as it may seem from a modern vantage point, the heroic opponents of slavery were commonly depicted in the terms reserved for conspiracy theory’s most despicable villains, e.g., witches, Illuminati, and Communists. South Carolina’s William Henry Drayton pictured “these conspirators … at their midnight meetings, where the bubbling cauldron of abolition was filled with its pestilential materials” (Davis, 35). An 1852 writer in DeBow’s Review of New Orleans actually compared abolitionism with communism (then newly invented), seeing them both as part of a blasphemous, hypocritical foreign campaign to overturn a social order ordained by “the thought of God” Himself: “What means this darkly-shadowed caricature of good—this horrible disfigurement of Christian charity—which, but that it stalks in terrible reality before us, would seem like the mockery of some fearful dream?” (L.S.M., 509).

From the Haitian Revolution on, slave rebellions real and imagined had been widely blamed on abolitionists, sometimes for just inspiring slaves from afar but increasingly, over time, for direct “intermeddling” with them. Some southerners even charged abolitionists with their slaves’ day-to-day insubordination, as well as the harsh discipline allegedly necessary to suppress this insubordination. Indeed, proslavery publicist Edmund Ruffin argued in 1857 that only “abolition action” prevented slaves from being “the most comfortable, contented, and happy laboring class in the world” (Ruffin, 549). Ruffin and other white southerners envisioned the abolitionists as a vast network of open agitators and allied secret agents who had fanned out across the South, undercover as salesman, ministers, and teachers, and coaxed slaves to escape or, better yet, slaughter their masters. “There is no neighborhood in the Southern States into which Yankees have not penetrated,” claimed Ruffin, “and could freely operate as abolition agents” (Ruffin, 546). This was a ridiculously inaccurate statement, of course, since by the time this passage was written it had long since become illegal as well as unsafe in most of the South to oppose slavery or even unenthusiastically support it.

Abolitionists in the North spoke and wrote in public forums, but were always suspected of secret designs and hidden agendas. Funding and organizing the subversion of slavery in the South was one accusation. Others included complicity in a British plot to break up the Union and/or a secret neofed-eralist stratagem to destroy the Democratic Party. Not surprisingly, these antiabolitionist theories often came from the ranks of northern Democrats eager to retain the favor of their southern wing.

Before detailing some of the more specific beliefs about the abolitionists, it is vital to put them in more realistic perspective than antiabolitionists usually provided. The idea of abolitionist involvement in engineering servile rebellion was mostly a fantasy, even in the case of the one abolitionist, John Brown, who actually tried it. Radical abolitionists were commonly sincere religious pacifists. Before Brown’s activities in the 1850s, almost no hard evidence exists of plots or nondefensive violence instigated by northern abolition activists. Abolitionists certainly protected fugitive slaves when they could, and aided some escapes in border regions and port cities, but they posed no physical and little economic threat to slaveholders, whose human and real property was worth more on the eve of the Civil War than it ever had been before. Moreover, radical abolitionists never enjoyed widespread political influence, and the charge that they dominated Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party (the so-called “Black Republicans”) was both a partisan slur and an important part of the southern conspiracy theory about the northern antislavery sentiment.

The term “Black Republicans” also contained another connotation. It was the habit of all slavery’s defenders (and their political allies) to conflate any degree of opposition to slavery with the most radical forms of abolitionism and egalitarianism they could imagine. So politicians and writers taking the much more widespread “free soil” position, opposing only slavery’s further expansion, were treated as outright abolitionists, and those who showed any degree of concern for black rights were likely to be denounced as advocates of full social equality with blacks and “amalgamation” of the races.

It should be noted that the situation as described above took several decades of U.S. history to fully develop. Negative attitudes and outlandish beliefs about abolitionists had long circulated in areas like the lower South and the Caribbean, where the extremely large slave populations left whites feeling nervous and outnumbered. These conspiracy theories became far more widespread with the radical-ization of antislavery that took place in the 1820s and 1830s.

From Moderation to Radicalism in the American Abolition Movement

Before the late 1820s, American abolitionism was almost painfully polite, tentative, and moderate. During the American Revolution, it came to be generally agreed outside the lower South that slavery was inconsistent with the egalitarians ideals of the Declaration of Independence and other revolutionary mission statements. The northern states abolished slavery in the years after the Revolution, though often by means of gradual emancipation laws that only freed the adult children of current slaves.

Quakers opposed slavery as a matter of conscience and lobbied for abolition during the First Congress, but without results. The bulk of antislavery activity in the early Republic was more Jeffer-sonian in approach, looking to end the international slave trade (which occurred in 1808) and find some means of phasing southern slavery out while minimizing economic and social disruptions. Slaveholders were to be compensated for their losses to abolition, and the creation of a large free black population would be avoided by sending former slaves to colonies in Africa or some other faraway place. This was the formula promoted by the early Republic’s most prominent antislavery organization, the American Colonization Society, which counted James Madison, Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, and Francis Scott Key among its members and enjoyed the official aid of the U.S. government and navy.

Despite the moderation of these early efforts, the slaveholding politicians of the lower South reacted harshly to the idea of even discussing limitations on slavery. The Carolinas and Georgia forced special protections and extra representation for slavery to be built into the federal constitution. The Quakers petitioning the First Congress were accused by South Carolina’s Aedanus Burke of being British spies who were “for bringing this country under a foreign yoke.” During the same debate, southern congressmen made veiled threats to leave the newborn Union if such discussions continued, arguing that “every principle of policy and concern for . . .

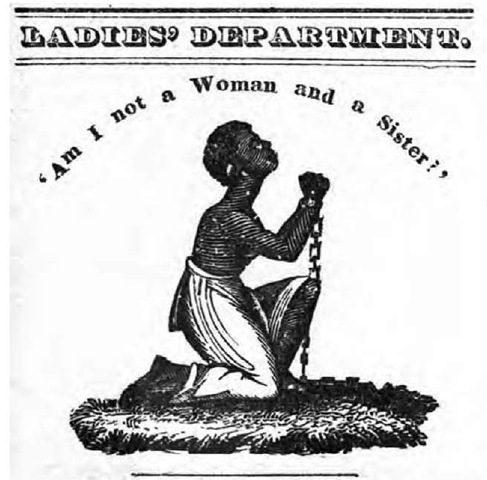

White Lady, happy, proud and free, Lend awhile thine ear to rae ; Let the Negro Mother’s wail Turn thy pale cheek still more pale. Can the Negro Mother joy Over this her captive boy, Which in bondage and in tears, For a life of wo she rears ? Though she bears a Mother’s name, A Mother’s rights she may not claim ; For the white man’s will can part, Her darling from her bursting heart. __ »—- From the Genius of Universal Emancipation. LETTERS ON SLAVERY.—No. III.

Ladies’ Department from “The Liberator,” published by William Lloyd Garrison, 1849. (Bettmann/Corbis) the peace and tranquility of the United States, concur to show the propriety of dropping the subject [of slavery], and letting it sleep where it is” (Debates and Proceedings in Congress).

When northern congressmen voted to exclude slavery from the new state of Missouri in 1820, much less than what the Quakers had asked, the uproar was far worse. Thomas Jefferson declared it “the knell of the Union” (Jefferson, 1434) and the Virginia capital was “agitated as if affected by all the Volcanic eruptions of Vesuvius” (Brown, 438).

Extremism in the defense of slavery was no vice, and moderation in the pursuit of abolition was increasingly not accepted as a virtue.

Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that black and many white abolitionists grew impatient with the moderate approach. Hence their rhetoric and tactics became much more radical beginning in the late 1820s. The new approach asked, in far less apologetic tones, for immediate, uncompen-sated abolition, without colonization, as a matter of moral right. Public notice of the shift in abolitionist thought was given by the appearance of three new abolitionist publications between 1827 and 1830: Freedom’s Journal, the first African American newspaper; white abolitionist printer William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper The Liberator; and, especially, the 1829 pamphlet An Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, by black used-clothing dealer David Walker. Walker and Garrison almost immediately became two of the most hated (and feared) men in all the South. Although the pamphlet itself was considerably less ferocious than its reputation, Walker’s Appeal became notorious for its defense (as a last resort) of violent resistance to slavery, and for its then-unusually apocalyptic warnings about consequences of continued oppression of the black population: “I tell you Americans! that unless you speedily alter your course, you and your Country are gone! ! ! ! !” (Walker, 1829).

What frightened southerners even more was the fact that Walker, who came from the South but lived in Boston, actually managed to distribute some of his pamphlets in the South. A parcel of sixty copies arrived in Savannah, Georgia, in December 1829, just after the pamphlet was published, and more were soon found in the Carolinas, Virginia, and Louisiana. One of the antebellum South’s frequent slave conspiracy panics quickly ensued. Numerous southern jurisdictions passed new laws against slave education and seditious or “incendiary” literature, of which North Carolina’s was one of the harshest. Writing, publishing, or circulating any publication tending to “to excite insurrection, conspiracy, or resistance in the slaves or free Negroes” was made a crime punishable by a year in prison and whipping for the first offense, and death for the second offense (Eaton, 124). Abolitionist activity actually became a capital crime in much of the South, and this was only the beginning of a decades-long campaign to purge ideological nonconformity from the region, at least as it pertained to slavery. Georgia newspaper editor Elijah Burritt had to flee for his life when it was discovered that he had received twenty copies of the Appeal at the post office.

Many southerners at the time, along with some historians, have suspected some connection be-tween’s Walker’s pamphlet and the 1831 Nat Turner slave rebellion in Virginia, in which fifty-five whites were killed. (Similar Walker links have been seen to a Christmas 1830 slave rebellion outside New Bern, North Carolina, but that outbreak was quickly and brutally suppressed before any whites came to harm.) Virginia governor John Floyd received a likely fraudulent letter from one “Nero” claiming that Turner’s raid was only the beginning. “Many a white agent” like Burritt was already in place, Nero claimed, and the slaves were also enlisting the aid of the removal-threatened Indians in Georgia (Hinks, 132). The most concrete link between Walker’s Appeal and Nat Turner was probably their common roots in the spiritual and political ferment that was roiling through American black communities around that time—there were serious slave uprisings in Jamaica and other Caribbean colonies during 1830 and 1831. Rumors of imminent abolition may have played a role in the unrest, but rumors hardly required a network of agents to spread.

David Walker died in 1830, but his legacy as chief bugbear of southern slaveholders was amply carried on by the rise of William Lloyd Garrison and other aggressive immediatists during the 1830s. Garrison’s Liberator was read mostly by a small audience of free blacks, but its most provocative passages seem to have been broadcast widely. Garrison argued in vitriolic terms not only for abolition, but also racial equality and the enfranchisement of blacks, stands that made him, in the minds of many suspicious southerners, a sort of evil poster boy for the whole antislavery cause and possibly for all of northern culture.

Garrison promised he would be “as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice” in his campaign against slavery: “On this subject, I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! no! Tell a man whose house is on fire, to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hand of the ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen” (Cain, 72). Later Garrison became even more infamous for denouncing the Constitution as “a covenant with death, an agreement with hell” because of its special favors for slavery. On at least one occasion Garrison publicly burned a copy of the document, endearing him to few northerners but burnishing his demonic credentials down south.

The Conspiracy Is in the Mail: The Furor over the Abolitionist Media Campaign

The new radical abolitionists were by and large products of the Protestant religious revival known as the Second Great Awakening. Following the example of the evangelists who had spread the Awakening, abolitionists developed an aggressive, media-savvy campaign of “moral suasion” aimed at converting white Americans to their cause. The American Anti-Slavery Society was founded for this purpose in 1833, and well funded by wealthy businessmen such as the Tappan brothers of New York. The new abolitionists sent hundreds of petitions to Congress asking for the abolition of slavery in Washington, D.C., where there was no constitutional question of states rights to get in the way. At the same time, beginning in the mid-1830s, they unleashed a multimedia assault on American public opinion the likes of which no one had ever seen before. Antislavery newspapers, magazines, pamphlets, slave narratives, touring speakers, musicians, songs, plays, and novels were all thrown into mix. In the process, the abolitionists became probably the first political group of any kind to send what we now call direct mail solicitations, or junk mail, literature sent directly to citizens that the citizen did not request. Most controversially, the abolitionists sent their literature into the South, usually in defiance of local laws passed a few years earlier.

The southern reaction to this campaign showed the depth of slaveholders’ fears about slavery. Even though slaves were 90-95 percent illiterate and alleged to be deeply loyal to their masters, southern leaders seemed to entertain the possibility that a few words on paper might bring down their whole house of cards. They became much more aggressive about taking the position that any discussion of slavery in any context was incredibly dangerous, a form of attempted murder against all southern whites. Abolitionist mailings were regarded in the same light that later generations would see letter bombs or pornographic “spam” e-mail. Northern capitalists were bankrolling the transmission of disruptive, alien values into decent American communities. Tennessee slaveholder and president Andrew Jackson thought that the abolitionists ought to “atone for this wicked attempt with their lives.” Southern postmasters refused to even handle the stuff, and matters were soon arranged politically so that they would not have to make the choice to violate their oaths of office.

In July 1835, the Charleston, South Carolina, postmaster put the abolitionist mailings in a separate bag, and that night a mob of so-called “Lynch Men,” led by former governor John Lyde Wilson, broke in and stole it. They then proceeded to make that “incendiary” literature live up to the term, making a bonfire with it that was cheered by some 2,000 spectators. Allegedly to protect the other less inflammatory mail, the Charleston postmaster asked that the postal service not accept further abolitionist mailings for the South into the system, and the postmaster in New York City, where the American Antislavery Society was based, agreed.

Postmaster General and Democratic political strategist Amos Kendall endorsed this decision and made it official policy. It was a federal crime to interfere with or refuse to deliver the mail, but Kendall argued that while federal officials had an obligation to execute the laws, they had a higher obligation to the communities in which they lived. If federal laws were “perverted” to destroy local communities, as the abolitionists allegedly had done, “it was patriotism to disregard” the laws (John, 271).

Southerners also began to insist that the North impose southern-style restrictions on abolitionist free speech. Between 1834 and 1837, the free states endured an intense wave of antiabolitionist rioting, much of it not spontaneous but orchestrated by Democratic politicians. Georgia Democrat John Forsyth wrote to New York presidential hopeful Martin Van Buren suggesting that “a little more mob discipline of the white incendiaries would be wholesome … A portion of the magician’s skill is required in this matter . . . and the sooner you set the imps to work the better” (Cole, 226).

Van Buren’s imps got to work. Beginning in 1834, they organized public meetings against abolitionism all over the North, and also orchestrated hundreds of riots and other acts of violence aimed at stopping the abolitionist media campaign, with abolitionist lecturers, meetings, and newspapers the primary targets. Not all of these attacks needed to be arranged, but it was frequently noted that many of the mobs consisted of not street thugs but pillars of the community, “gentlemen of property and standing” (Richards). The tragic culmination of this anticonspiracy conspiracy was the 1837 riot that killed one especially persistent abolitionist editor, Presbyterian minister Elijah P. Lovejoy, who was shot defending a new printing press—earlier mobs had destroyed three others—in Alton, Illinois.

The controversy only died down once abolitionism was once again forced partly back into the political closet. This was one goal of the mail ban, and the main objective of the so-called “gag rule” that Congress imposed from 1837 to 1844, automatically tabling all petitions about slavery and thus preventing their official consideration.

Toward the Civil War

Though Congress was able to avoid the slavery issue until the Wilmot Proviso reopened it in 1846, neither the issue nor the abolitionists nor fear of the abolitionists went away until after the Civil War. During the late 1830s and 1840s, some anti-slavery activists became disenchanted with “moral suasion” and split with the Garrisonians, turning to the strategy of creating an antislavery political party. The political abolitionists also had difficulties with the increasingly prominent role of nontraditional political actors—blacks and women—in the movement.

At the same time, southern fears of antislavery conspirators and southern intolerance of dissent grew worse by the year. No proselytizing was required to get in serious trouble with the proslav-ery thought vigilantes. In 1856, respected University of North Carolina professor Benjamin Sherwood Hedrick, and a colleague who defended him, were forced out of their jobs. Hedrick had admitted, in response to a question, that he might have voted for Republican candidate John C. Fremont, if Fremont had even been on the ballot.

As southern intransigence deepened and the Slave Power seemed to grow stronger, abolitionists became more attracted to the direct action strategies of which southerners had long suspected them. Yet while rescuing fugitive slaves or moving west to keep Kansas free became popular missions for some, the idea that “vile emissaries of abolition, working like the moles under the ground” (Eaton, 100), were out engineering rebellions and “stealing” large numbers of slaves remained chiefly a southern conspiracy theory.

The famed Underground Railroad, for instance, was promoted almost as heavily by proslavery editors and politicians as it was by the abolitionists. There really was a network of people in the North, especially in Ohio and other states near slave territory, who helped escaped slaves make their way north, but it was never as large, well organized, or elaborate as the term “Underground Railroad” suggests. The modern practice of designating historic homes of abolitionist sympathizers as “stations” along established “lines” exaggerates the historical reality. Abolitionists often used the new metaphor of a railroad to describe the coming of freedom as a train that was moving forward and could not be stopped—”Get Off the Track!” was a popular abolitionist song, especially as performed by the anti-slavery singing stars, the Hutchinson Family Singers. Abolitionist publications liked to tweak southern fears by running joke advertisements for fictitious railroads like the “Liberty Line,” with many veiled references to the aid that escaped slaves would be given and a satirical drawing of blacks and whites riding in a literal train.

Once John Brown supplanted William Lloyd Garrison as chief abolitionist archetype in southern conspiracy theories after the 1859 raid on Harper’s Ferry, secession and civil war came to seem absolutely imperative to many southerners. Here was just what they always knew the abolitionists wanted. Brown’s plan for his “Provisional Army of the North” called for an armed assault on slavery in which a few northern whites and free blacks would set off a bloody race war. The plan failed dismally of course, but it had the backing of wealthy, important men back in New England. Moreover, Brown’s dignified behavior and passionate speeches against slavery at the trial and in newspaper interviews made him a hero in the North, confirming all southern fears about what little regard their countrymen had for their safety. Southerners had been chilled by some of the implements that Brown had with him when captured, such as hundreds of custom cast-iron pikes to be handed out to freed slaves, and a map full of mysterious marks at locations all over the South. Down South, these marks were widely interpreted as locations where Brown had slave allies or white agents planted and ready to strike.

The Harper’s Ferry raid and the North’s reaction to it set off a “crisis of fear” in many parts of the South that continued right through the beginning of the war. Vigilance committees in many localities launched a wave of further terror and repression against suspected abolitionists. Even talking to blacks, or looking like an abolitionist, became dangerous. A free black barber in Knoxville, Tennessee, was mistaken for Frederick Douglass and chased through the streets. A stonecutter working on the new South Carolina state capitol was whipped, tarred, feathered, and deported for a stray remark.

This was the mood of South Carolina when Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, in a four-way race that allowed to him to win even though he received no southern votes at all. With a Black Republican in the White House, paranoid South Carolinians saw no choice but to do what they had been threatening to do for years, secede from the Union. Only by separating from the American Republic could they be safe from the hordes of John Browns and pike-wielding blacks that Lincoln would surely send.