Hinduism, the dominant religion of India, distinguishes between two forms of sexuality. The first is sex for pleasure and procreation; the second is sex in its mystical and magical aspect. In the latter case, power is achieved by control over sexual activity. The first category forms the subject of much of Indian writing on sex, and sexual love is treated as one of the purposes of life and its enjoyment is extolled in numberless passages in Indian literature. Sex in its magical or mystical aspect is also prominent and, as in ancient China, there is great concern that the loss of semen might cause a man to lose his vital energy and sustain a spiritual loss. Two methods are employed to obviate these hazards. One is the ascetic method of absolute continence, and continence is one of the major virtues of the Hindu ethical code. The other method is the technique of nonspilling of the seed and involves the learned technique of coitus reservatus. In modern India, however, it is the concept of sex for pleasure that seems to dominate and the burgeoning population of India is fast heading toward the billion mark.

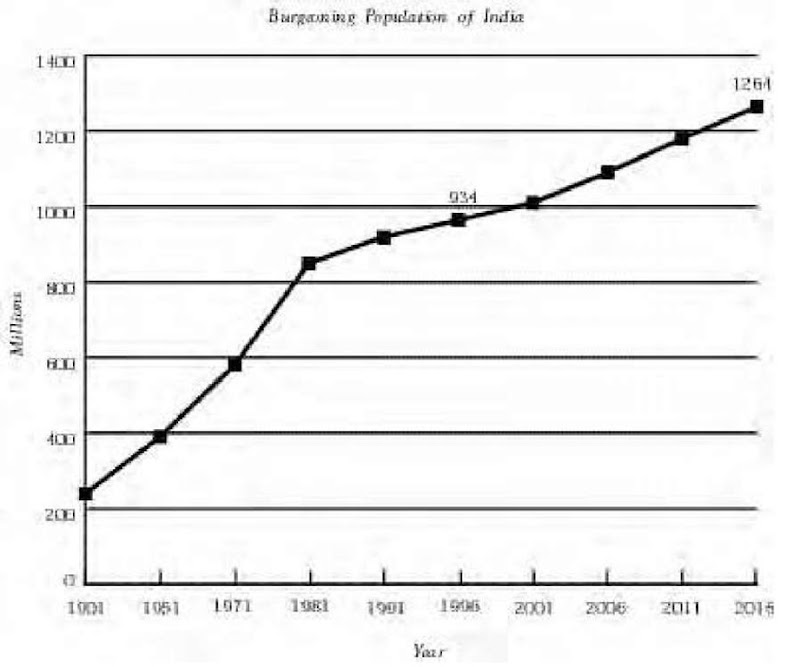

Figure I.1 Population Growth in India

Rapid population growth took place between 1951 and 1981 and was somewhat slower between 1981 and 1991. The rate of population growth has been 2.12 percent per annum and is estimated to grow not less than 1.5 percent per annum during the next twenty years because of the high rate of growth of the already large population base. The Indian population is a young population, with 36.3 percent under fourteen years old and another 10.8 percent between fifteen and nineteen years of age.

Population growth in India cannot be seen in a single and simple perspective because of the nonhomogeneous cultures present in the country. India consists not only of a huge population and a vast geographical area but also has nine major religions, sixteen major languages with four hundred dialects, and more than three hundred castes distributed over twenty-six states, each trying to preserve its separate identity.

As a result of this diversity, states such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh demonstrate a high total fertility rate and low Human Development Index, whereas states such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu have a low total fertility rate with a high Human Development Index. This aggregate socioeconomic indicator tracks progress in longevity, education, and income as measured against life expectancy at birth, adult literacy, mean years of schooling, and income. The diversity of effects of these factors in India is obvious from Tables I.1 and I.2.

In the context of the heterogeneous character of the Indian population, the sociocultural aspects of life play an important role in population control.According to most anthropologists, culture encompasses learned behavior, beliefs, attitudes, values, and ideas that are characteristic of a particular society or a population. A case study of Kerala and Tamil Nadu on one hand and

Table I.1: Comparison by State of Population Indicators

|

|

|

Median Average |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Average |

Age of Marriage |

High |

|

Contraceptive |

|

|

|

|

Population |

Growth Rate in |

25-49 |

Order Births |

Total |

Acceptance % |

|

Couple |

|

|

in Thousands |

Percentages |

Female Age |

4+% |

Fertility |

1991-1993 |

|

Protection |

|

State |

(1996) |

(1990-1996) |

Group |

Age |

Rate |

Spacing |

Stopping |

Rate |

|

India |

934,218 |

1.98 |

16.1 |

23.4 |

3.5 |

5.5 |

30.9 |

43.9 |

|

Bihar |

93,005 |

1.48 |

14.7 |

33.7 |

4.6 |

2.9 |

18.6 |

24.7 |

|

U.P. |

156,692 |

2.38 |

15.1 |

34.7 |

5.2 |

5.4 |

13.1 |

33.7 |

|

Kerala |

39,065 |

1.24 |

19.8 |

6.6 |

1.7 |

6.1 |

48.3 |

55.4 |

|

Tamil Nadu |

59,052 |

1.50 |

18.1 |

9.2 |

2.7 |

5.7 |

39.5 |

57.3 |

Bihar and Uttar Pradesh on the other can elucidate this concept further.

Kerala, the best, and Tamil Nadu, the next best states on the Human Development Index, are both southern Indian states that have had historically very little Muslim influence. Kerala also never came under the influence of Brah-manic culture, in which women were denied education and most of the individual human rights. In Kerala, a predominantly matriarchal state ruled by progressive Indian rajas who always promoted education, a woman played an important role in social life.Today Kerala has the most educated population, with 98.6 percent enrollment in primary schools and 86 percent female literacy. Tamil Nadu, though next best, is not very close to Kerala in overall human development, that is, providing food, clothing, shelter, education, medical aid, and employment to every person. There was no Muslim influence in Tamil Nadu, which came in contact with the West in the nineteenth century. Fast spread of education thereafter helped to liberate Tamil Nadu from the suffocating Brahmanic culture.

Bihar and Uttar Pradesh on the other hand happened to be the hotbeds of Brahmanic counterrevolution, which threw Buddhism out. Bihar, the birthplace of Mahaveer and Gautam Buddha— both rebels against the Brahmanic culture—and the seat of the University of Nalanda (where scholars came to study from all over the East), fell under Muslim domination in the thirteenth century, as did Uttar Pradesh. Traditional social life was smothered. Women were pushed behind the purdah and their development stopped completely. These two states continued to remain in the backwaters of India despite the fact that a number of India’s national leaders hailed from these two states. Most of the population in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh remained in the clutches of landlords, both Hindu and Muslim.The result has been rampant child marriages, illiteracy, lack of economic development, and discontinuation of traditional beliefs and living styles.

Median average age of marriage in the age group of 25 to 49 years in Kerala is 19.8 and in Tamil Nadu it is 18.1, whereas in Bihar it is 14.1 and in Uttar Pradesh it is 15.1. In Bihar and Uttar Pradesh the total fertility rates are 4.6 and 5.2 per woman, respectively, which are higher than the Indian average of 3.5. Similarly, the high order birthrate (those with four or more children) is 33.7 and 34.7 in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, respectively, as compared with 6.6 and 9.2 in Kerala and Tamil Nadu, respectively. Contraceptive acceptance in these northern states is also low. Even if we combine spacing methods and sterilization as methods of birth control, in Bihar the rate of women using birth control is 21.5 percent and in Uttar Pradesh it is 18.5 percent, with overall couple protection rates, respectively, of 24.7 and 33.7 percent.The two southern states have a contraceptive acceptance, respectively, of 54.4 and 45.2 percent, with a couple protection rate of 55.4 and 57.3, respectively. The female literacy rate in Bihar is 18.3 percent and in Uttar Pradesh it is 20.6 percent, and though life expectancy at birth for women has increased, the life of women has not changed—particularly in the rural areas. The political will to change the situation is generally nonexistent all over India and particularly so in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. In these two states the percentage of people below the poverty level, 54.96 in Bihar and 40.85 in Uttar Pradesh, is also higher than that of the Indian average. All these figures clearly indicate that the general development of the population and particularly the education of women, the crucial factor in contraceptive acceptance, is particularly absent in these two states.

Table I.2: Comparison by State of Development Indicators

|

|

|

Life Expectancy |

Adult |

Maternal |

Crude |

|

|

|

|

Gender |

|

|

|

No. of |

at Birth |

Literacy |

Mortality |

Birth |

|

|

|

|

Related |

Reproductive |

|

|

Women per |

1989-1993 |

1981-1991 |

per 100,000 |

Rate |

IMR 1996 |

U5 MR |

Health |

Health |

||

|

State |

1,000 Men |

M F |

M F |

Births 1995 |

1992 |

M |

F |

M |

F |

Index |

Index |

|

India |

927 |

59.0 59.7 |

62.4 33.9 |

453 |

29.1 |

78 |

78 |

119 |

132 |

49.82 |

42.21 |

|

Bihar |

911 |

59.7 59.2 |

55.3 18.2 |

470 |

31.7 |

69 |

72 |

117 |

140 |

43.51 |

30.48 |

|

U. P. |

879 |

56.5 55.1 |

53.6 20.6 |

624 |

36.0 |

91 |

102 |

145 |

180 |

33.39 |

22.80 |

|

Kerala |

1,036 |

68.8 74.7 |

91.7 86.0 |

87 |

17.8 |

18 |

13 |

30 |

25 |

88.12 |

84.61 |

|

Tamil Nadu |

974 |

61.4 63.4 |

65.0 35.8 |

376 |

21.8 |

58 |

56 |

79 |

84 |

1.21 |

63.60 |

Even when one considers the falling death rate in India, it must be remembered that the death rate did not decrease because of betterment of life per se, but rather it resulted from the cumulative impact of modern drugs, effective epidemic control, and various vaccinations. The Human Development Index continued to remain low, emphasizing a lack of desire to improve the standard of living, a desire that is a key to motivation for reducing the birthrate through contraception strategies. Fault lies in restriction of literacy to only a very few upper class and caste people and a lack of serious efforts to dispel the deep-rooted fatalistic outlook held by the majority of the people who have been deprived of so much for so long. Unfortunately, even by the end of the twentieth century, this vicious circle of ignorance, poverty, fatalistic attitude, and population growth has not been attacked, and the political leaders have not yet faced the fact that the problem of population growth in India cannot be discussed and managed in isolation but has to be a part of the human development program.

The techniques of contraception are not new to modern India. As early as 1921, Professor R. D. Karve, assisted by his wife Malati, started a Family Planning Clinic in Mumbai (Bombay) and helped many middle-class couples to learn the use of the diaphragm and condom. Karve also emphasized the importance of education in establishing better contraceptive practices, but his movement was primarily restricted to the educated middle class.

In the early 1950s, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, stated that the population problem was not just one problem but 400 million, at that time the population of India. He emphasized that population issues were part of the overall problem of development—providing food, clothing, shelter, education, medical aid, and employment for everyone. No Indian government has ever quite managed to tie all these elements together. When Nehru’s government in 1952 officially adopted the Population Control Program and put it under the Ministry of Health, it was independent of development, that is, government efforts toward population control were separate from government efforts toward other areas of human development. The then-minister of health promoted the rhythm method for preventing pregnancy. This was doomed to fail in an illiterate population that had no scientific knowledge of the menstrual cycle and so had no way to comprehend the concept of a “safe period.”

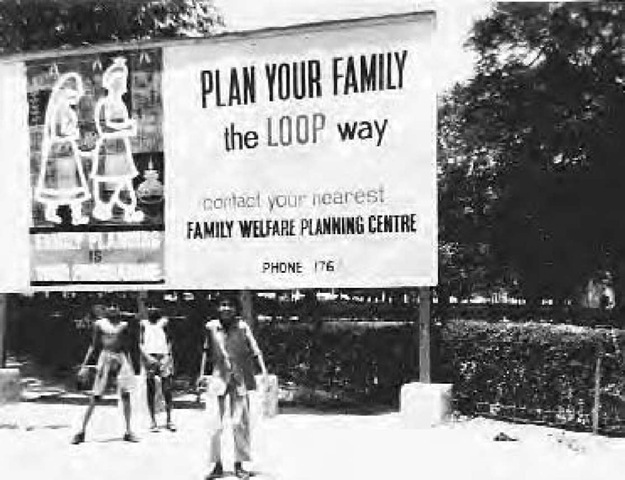

A billboard advertises the family planning program in New Delhi, India.

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) became active in India. The first countrywide family planning NGO was started in 1952 by Dhanavanthi Rama Rau, who established the Family Planning Association of India, which popularized the use of the diaphragm and condom. These efforts were essentially clinic-based and included little patient education.

Successive governmental programs hardly made any headway in solving the population problem until 1965 when the intrauterine device was accepted officially as a contraceptive and the pill got recognition in 1966. Hospital-based training programs were undertaken to educate the medical profession and family planning officials. Cash incentives were offered to promoters, motivators, and acceptors. Oral contraceptives could be obtained from government hospitals or bought (at a high cost) on the open market. Female sterilization remained mainly a postpartum operation and the husband’s written consent (which rarely was granted) was made mandatory.

In 1972, the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act was passed, legalizing abortions for various reasons, of which “contraceptive failure” happened to be one. It was a virtual and blanket permission for abortion on demand. During 1975 and 1976, the family planning program received its severest setback. The government vigorously promoted (read “forced”) vasectomy, giving cash incentives to promoters, clients, and medical personnel involved. Mass sterilization camps for both men and women were organized. Vasectomy centers were set up even on suburban and local railway platforms. The effort was soon perceived by much of the population to be a massive program of coercion and/or corruption, particularly in terms of the bonuses given to promoters and medical personnel. The negative impact of this period brought about the fall of the ruling government.

Since then, no political party has dared to actively propagate any intensive action regarding family planning. In fact, “family planning” was renamed “family welfare” and later became a part of the Maternal and Child Health Program. These programs then became part of the Child Survival and Safe Motherhood Program and later the Reproductive and Child Health Program. The association of family planning combined with development, proclaimed at least as an ideal by Nehru, disappeared, even though at the Bucharest World Congress on Population in 1974 the Indian delegation promoted as its slogan: “Development is the best contraceptive.” The concept of family planning as an integral part of development efforts has remained neglected even today.

An overview of the governmental Population Control Program in the last three decades summarizes the attempts to spread some form of population control, though not always successfully.

1) Uniform and centrally planned program for the entire country is executed through the central government.

2) Existing state government infrastructure is used in varied sociocultural grass-roots environments.

3) Information about various methods of contraception is delivered through a health delivery network of 20,719 primary health centers and more than one million subcenters in rural India (1992).

4) Contraception information and methods are delivered by primary health care workers of different categories such as auxiliary nurse mid-wives, village health guides, community health volunteers, multipurpose workers, and traditional birth attendants.The terminology of these categories of workers varies at different places due to lack of coordination.

5) In urban areas these services are provided through a network of government or municipal (city) hospitals and clinics and also the urban welfare centers specially established for this purpose. Private-sector hospitals, clinics, and dispensaries also provide family welfare services.

6) Until as late as 1998, health practitioners at all levels were given targets for the number of intrauterine device placements and sterilization operations they were to perform.

7) Cash incentives are being given to clients and motivators.

8) Laparoscopic female sterilization has been promoted so much that vasectomy has stopped receiving any serious attention.

9) Media publicity is restricted only to slogans and so-called benefits of family planning. There are hardly any explanatory demonstrations of use of contraceptive devices, probably because of the (imaginary) belief of promoting permissive sexual behavior. No relevant educational programs such as sex education, marriage counseling, and contraceptive promotion are undertaken by the concerned agencies.

10) Cash incentives are given to couples getting sterilized after having one or two daughters.

11) Condoms are publicized more as an AIDS preventive measure than as a contraceptive.

It is possible that each one of the above actions could be counterproductive, or at least ineffectual, from the point of view of population control strategy.

Surveys of socioeconomic characteristics continue to demonstrate that the percentage of unmet needs for family planning remains especially high for the following segments of the population: rural men and women, illiterate women, illiterate husbands, Muslim women, tribal women, and women not yet exposed to media messages on family planning.

The unmet need for child spacing, however, varies according to age, number of living children, number of living sons, and to some lesser extent by child loss. Dr. Radhadevi et al. found that among currently married women with unmet needs for family planning only 26 percent intend to use contraceptives for spacing. Of the 74 percent who did not intend to do so, 62 percent give as their reason that they want more children. This emphasizes that simply revamping the family planning services would not make much difference to contraceptive acceptance unless there are effective educational programs demonstrating the importance of child spacing.

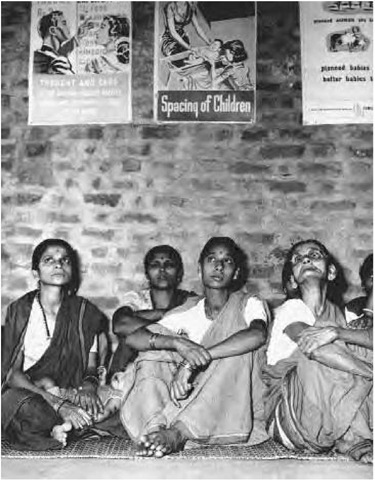

Indian women wait their turn at a birth control clinic.

Table I.3: Education of Husband and Wife and Average Number of Conceptions

|

|

|

|

|

Number of |

|

Education |

Number of Men |

Percentage |

Number of Conceptions |

Living Children |

|

Nil |

278 |

29.4 |

3.122 |

2.399 |

|

Primary |

467 |

49.4 |

3.077 |

2.441 |

|

Secondary |

154 |

16.2 |

1.9991 |

1.370 |

|

Higher |

26 |

2.7 |

1.981 |

1.700 |

|

|

Number of Women |

|

|

|

|

Nil |

616 |

65.0 |

3.105 |

2.072 |

|

Primary |

271 |

28.7 |

2.631 |

2.092 |

|

Secondary |

44 |

4.6 |

2.009 |

1.705 |

|

Higher |

11 |

1.1 |

1.454 |

1.173 |

Table I.4: Total Fertility Rate by Population Group

|

Annual Income |

|

Adult Literacy |

|

Village |

|

|

in Rupees |

TFR |

Group |

TFR |

Development Group |

TFR |

|

Up to 20,000 |

4.9 |

None Literate |

5.3 |

Low |

5.3 |

|

20,000-40,000 |

3.8 |

Female Literate |

2.9 |

Medium |

4.2 |

|

40,000-62,000 |

3.5 |

Male Literate |

5.0 |

High |

3.4 |

|

62,000-86,000 + |

3.2 |

Both Literate |

3.3 |

All India |

4.3 |

In 1969 to gauge community perception about family planning, Streehitkarini conducted a family and fertility survey of nine hundred families in the slums of central Bombay. The survey demonstrated that women’s education was the key factor in population control.The level of the woman’s education influenced the number of conceptions as well as the child survival, both essential for reducing the need for more children. Other studies have continued to emphasize the importance of female education, as Abusaleh Shariff reports in Tables I.3 and I.4.

It has been the experience of birth control workers worldwide that no educated woman would deprive her children of education. Education leads to self-confidence and enhances deci-sionmaking power, and this in turn leads to social change. Jawaharlal Nehru was correct many years ago when he emphasized the need to address development and population problems together. Social change in India is needed urgently. For more than two centuries Western experts have known that women play a crucial role in social change as well as in population growth. It is difficult not to connect greater literacy with rising hope and expectations. This transition has yet to happen in Indian society.

Other countries have faced the problem of controlling population growth more effectively than India has. For example, the experience in both Indonesia and Iran shows that family planning programs have to be an integral part of the national strategy for development. In the Indonesian program at least six ministries are involved. Ministers of health, religious affairs, information and broadcasting, education, industry, and the home ministry all work together. At no time were any incentive payments made to induce participation in the family planning effort. The only promise was that of a “small, prosperous and happy family” to those who become regular program participants.

A customer walks out of a birth control store in Calcutta, India

In Iran total acceptance of all methods of contraceptives was only 37.0 percent in 1976 but by 1997 it had risen to 72.9 percent. The birthrate per 1,000 population was 43.4 in 1986, and in less than a decade it declined to 24.3, reaching 20 by the time it was presented to the Conference on Population and Family Planning at Tehran. Female literacy and other factors played a role in this success. In 1976 only 36 percent of the females above the age of six were literate but by 1996 this increased to 74 percent. For rural women it was 62 percent in 2000. More Iranian women are working or intending to work once they finish school, which also influences people’s attitude toward family size. Perhaps the most important contribution toward the family planning program success has been the interest, support, and guidance of the religious leaders.Their backing developed within a context of the religious flexibility regarding social issues. There is little doubt about the effectiveness of the positive fatwa (direction given by Islamic leaders), originally issued by Ayatollah Khomeini in 1980, regarding the use of contraceptives.

These two examples from so-called underdeveloped countries should stimulate the Indian government to apply itself seriously to women’s education and human development rather than merely to propagation of family planning services. NGOs should play a more meaningful role, not only in demanding more equitable laws but also in finding more innovative ways to bring about changes in education and health care systems. A few NGOs are working at this but, com pared with the size of the country and the population, they seem to be getting lost in the sea of ignorance and poverty. The innovations and experiments carried out by some of these NGOs are publicly applauded but never replicated or put into practice on a large scale, which could be done only by the governmental agencies.The fault lies with the bureaucratic and mechanical approach in training grass-roots personnel.

Dr. Ashish Bose, a demographer, has described India’s family planning program as having three major gaps: communication, credibility, and creativity. The communication gap exists because the thinkers, intellectuals, sociologists, and workers have no direct communication with the illiterate masses. They instead depend upon the politicians to communicate the right message. The politicians, because of their vested interests, never talk adequately about the family planning program lest their outspokenness affect their vote banks.

The credibility gap exists because the belief in family planning programs in India is at a nadir because neither the politicians, bureaucrats, nor even the people who are likely to derive the benefit are taking responsibility for population control. The focus is misdirected when it is only toward the so-called Minimum Needs Program while development is ignored. Even the Minimum Needs Program remains mostly on paper.

The last gap that Bose describes is “the creativity gap,” by which he means that we have failed to generate new ideas, look for innovation, and tackle bold initiatives, even at the cost of failure. The safe policy that is being pursued has taken its toll and made the Indian masses continue to live in misery and inhuman conditions.

In an interview in the Times of India—Mumbai on World Population Day, Indian scientist Dr. Vasant Gowarikar, former director of Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre and a member of the Central Population Committee of India, said

The crucial breakthrough in India’s population growth pattern occurred between 1981—91 when the birth rate declined faster than the death rate.

We are currently witnessing the first stage of transition, which will lead to a stabilized population growth by early next century. . . . When I claim that India has turned the corner it is a claim about choice [I mean] . . . people are increasingly choosing to have fewer children.

Gowarikar does not deny the valuable role played by literacy in checking the population growth but yet asserts the overriding role played by people’s wisdom. He further says, “If we are given only two things to choose I would go on war-footing to make India fully literate and [give it an] energy surplus within three years.” These two goals would help people without hurting any interest groups and ideology.

People’s development is the crucial factor in population control. As the pioneer in contraceptive service, Dr. R. D. Karve, cited earlier, said more than fifty years ago, “No one will practice birth control to meet the danger of growth in population. People will practice it for their individual good.” India needs, as Nehru said, to improve the quality of life of the individual. Providing education and making quality contraceptive services available to every person is a start. Crucial in this is upgrading the role and status of women. In the Stree-hitkarini survey in 1988, 98 percent of the women surveyed wanted to educate their daughters so that they would not have to face the same drudgery that they themselves had to. To be free to develop, a woman needs education, contraceptives, and an income of her own. This would start the much-needed social change that would help India to overcome the population crisis.