Until the nineteenth century, folk remedies for abortion and superstitions about abortion essentially remained unchanged over the centuries. In the nineteenth century the selling of abortive products became a commercial business, although older more interventionist methods continued to be available. Technically, most of the remedies available did not mention the word abortion but went under such suggestive names as the “Female Regulator,” “Uterine Regulator,” “Woman’s Friend,” “The Samaritan’s Gift for Females,” and many others. Most of the remedies were described as having the imprimatur of science behind them. The label on Graves Pills for Amenorrhea stated, for example,

These pills have been approved by the Ecole de Medecin, fully sanctioned by the M.R.C.S. of London, Edinburgh, Dublin, as a never-failing remedy for producing the catamenial or monthly flow. Though perfectly harmless to the most delicate, yet ladies are earnestly requested not to mistake their condition [if pregnant] as MISCARRIAGE WOULD CERTAINLY ENSUE. (Quoted by Brodie, 1994, p. 225)

Many of the pills simply commercialized traditional remedies such as tansy, pennyroyal, aloes, hellebore, rue, ergot, and cotton root. The medicines were often effective. In fact, as late as 1939, the Federal Trade Commission forbade the sale and advertisement of a number of compounds designed to regulate menstruation on the grounds that the compounds posed serious health hazards. If advertised drugs and potions were not effective, there were instruments available to assist. The American Medical Times in 1863, under the title of “Instruments of a Notorious Abortionist,” described forty simple instruments ranging from spoon handles bent in various shapes to pen holders with attached wires to actual forceps (Brodie, 1994, 226). There were also professional abortionists who were not yet forced underground.

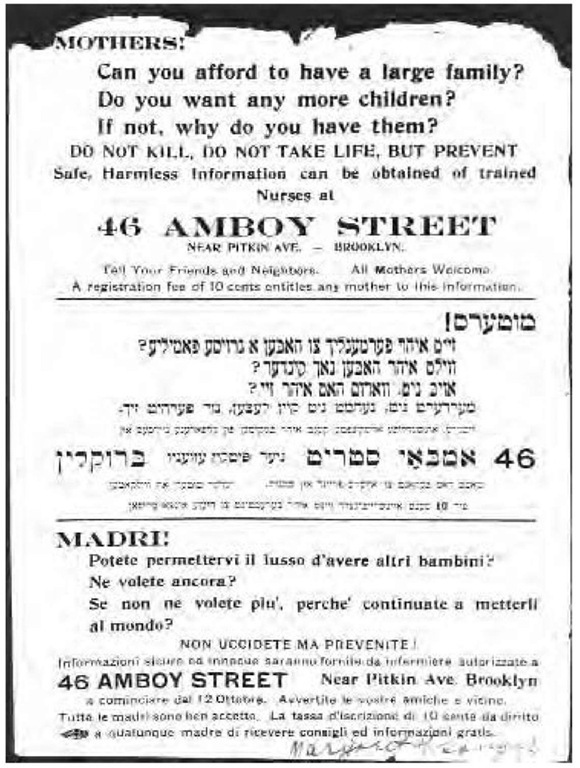

Margaret Sanger, seeing the need for women to obtain birth control instead of seeking back-alley or self-induced abortions, opened the Brownsville Clinic in Brooklyn, NewYork, in 1916.

A physician in the small farming town of Atkinson, Illinois (population 300) wrote in 1874 that he knew three respectable married women who were notorious for giving instructions to their younger sisters on ways of getting rid of an unwanted pregnancy. If tansy, savin, ergot, cotton root, lifting, or riding trotting horses failed, a knitting needle was a good standby. Other enterprising individuals developed their own methods. Frank Harris in his erotic biography described how he and his lover made a pencil of ingredients that swelled slowly with body heat so that once inserted into the cervix it caused an abortion.

Increasingly, however, there were legal restrictions put on abortion. For much of American history, abortion had been treated according to the common-law tradition in which abortions before quickening were not punishable. Those procured later in pregnancy might be high misdemeanors if the woman died, but not felonies. As criminal code revisions began in the various states, replacing the common law, abortion was often singled out for attention. The laws varied. In Connecticut, Missouri, and Illinois, abortion restrictions came in the form of tighter laws against the use of poisons. The first state to make an abortion a crime was New York, which in 1829 prohibited anyone, including a physician, from attempting abortion at any period of pregnancy except to save a woman’s life. The state then proceeded to legalize abortions done by physicians when the mother’s life was at stake, delegating to the medical profession the control of abortion. Most states followed this same delegation of authority.

Inevitably abortion began to go underground. Many of those providing such abortions were women. Perhaps the best illustration of the prevalence of women abortionists is the case of Elizabeth Blackwell, who is generally recognized as the first woman in the United States to graduate from a medical school. When she tried to establish her practice in New York City in the 1850s, she was denied rental at the first few boarding houses she approached because the landlords mistook her for an abortionist.

Probably the best-documented abortionist was Madame Restell, actually Ann Trow Lohaman (1812-1877), who ran a mail order business and abortion service in New York City from the 1840s through the 1870s. Because technically, as indicated above, abortion by non-physicians was illegal in New York state, Restell was often arrested, although only once was she sentenced to a term in prison. Mostly she was tolerated by the law enforcement officials, and she grew famous and wealthy, leaving an estate of more than a half-million dollars when she died. She was not alone, and abortionists who were arrested were often not found guilty, particularly if abortion took place before quickening.