Laboratory Tests

Biopsy is most useful in excluding causes of nonvasculitic pur-pura such as amyloidosis, leukemia cutis, Kaposi sarcoma, T cell lymphomas, and cholesterol or myxomatous emboli. Tissue im-munofluorescent staining is useful to support the diagnosis of Henoch-Schonlein purpura (specifically, IgA staining), SLE, or infection (the percentage of cases with positive results on immuno-fluorescent staining is not known). The cells infiltrating and perhaps destroying the vessel wall may be neutrophils or lymphocytes, depending on the etiology. The pathology in most cases of small vessel vasculitis is leukocytoclastic angiitis (LCA). Hepatitis C infection should be excluded routinely in patients who present with unexplained purpura—an important example of the fact that even the demonstration of LCA does not indicate that a patient’s illness is the result of a primary vasculitic syndrome.

Clinical subsets

Henoch-Schonlein Purpura

Henoch-Schonlein purpura is a clinically defined small vessel vasculitic syndrome in which cutaneous features are usually striking and in which significant visceral involvement is less common. Henoch-Schonlein purpura, which occurs less frequently in adults than in children,5 is usually associated with vascular and renal deposition of IgA-containing immune complexes. Common manifestations of Henoch-Schonlein purpura include purpura; urticaria; abdominal pain; gastrointestinal bleeding or intussusception (mostly in children); arthralgias or arthritis; and glomerulonephritis. Visceral symptoms may precede the skin lesions. Henoch-Schonlein purpura may be precipitated by medications or streptococcal or viral infections. It is usually a self-limited disorder, but the associated glomerulo-nephritis may, in rare instances (most often in adults), progress to renal failure. In the absence of renal dysfunction, Henoch-Schonlein purpura is often a self-limited but frequently recurrent syndrome that may require only symptomatic therapy.

Urticarial Vasculitis

Urticarial vasculitis represents a peculiar subset of small vessel vasculitis.6 The clinical presentation is that of wheals or serpentine papules, sometimes with surrounding or geographically separate angioedema. Individual lesions are slow to resolve, often lasting for several days; the disease follows a more prolonged course than typical urticaria. There is frequently a burning, dysesthetic discomfort from the lesions. Like purpura, the lesions of urticarial vasculitis are frequently located in gravity-dependent areas and often heal with skin hyperpigmentation or an ecchymotic area. Most cases are idiopathic, although an association with an underlying systemic autoimmune disorder such as SLE, IgM paraproteinemia, or a viral infection has been described. In rare cases, urticarial vasculitis has been associated with a syndrome that includes hypocomplementemia and interstitial pulmonary disease. This syndrome is distinct from C1 esterase deficiency associated angioedema, which does not cause urticaria.

Treatment

Therapy for cutaneous vasculitis is first directed at eliminat- ing any underlying precipitant. Infectious etiologies should be sought out and treated. Potential offending drugs should be withdrawn. Association with myelodysplasia and myeloprolif-erative disease should be considered, especially if there are any hematologic abnormalities. If no precipitants are apparent, low-risk therapy can be attempted with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, colchicine, pentoxifylline, dapsone, or short-term low-dose corticosteroids. Long-term corticosteroid therapy should be eschewed if at all possible. Compressive support stockings or panty hose may be useful in limiting the significant edema that often accompanies cutaneous vasculitis of the legs.

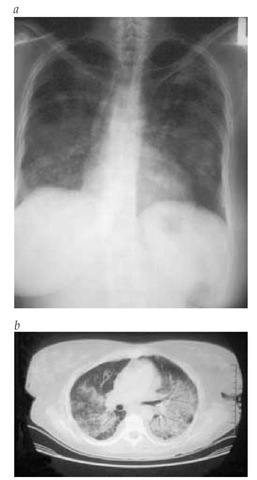

Figure 4 The nodular infiltrates of the lung in Wegener granulomatosis are shown less extensively in a standard radiograph (a) than in a computed tomographic scan (b).

Visceral involvement with organ dysfunction may necessitate a more aggressive approach than that used in limited cutaneous vasculitis. Moderate-dose corticosteroids are generally effective. In the setting of potential complications from chronic corticosteroid use or the setting of severe visceral involvement, methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, or other im-munosuppressive agents may occasionally be required [see Table 2]. When treating chronic, refractory small vessel disease that is not organ or life threatening, one must pay close attention to the risk-to-benefit ratio of selected therapies.

Wegener Granulomatosis

WG is a relatively uncommon, potentially lethal disease characterized by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and vasculitis of small and medium-sized vessels.7,8 Males and females of all ages can be affected.

Diagnosis

Clinical Manifestations

WG is characterized by parenchymal necrosis with a variable contributory component of vasculitis. Multiple organs are often involved; there is a predilection for the upper and lower respiratory tracts, eyes, and kidneys.

Upper respiratory tract involvement Upper airway disease may be striking but is often attributed for months or even years to routine sinus disease until other manifestations of WG are recognized. Even after the diagnosis is made and immuno-suppressive treatment is provided, sinus disease may be recalcitrant to therapy. This chronicity may be caused in part by super-infection of damaged tissue by Staphylococcus aureus. Anatomic damage can include septal perforations and saddle-nose deformities. Laryngotracheal involvement may result in subglottic stenosis, which is best treated by local corticosteroid injection therapy. Ear involvement is common, particularly otitis media, which may produce conductive hearing loss. Orbital pseudotu-mors may cause proptosis with intractable pain and loss of vision; these inflammatory and fibrous masses may be refractory to anti-inflammatory therapy, immunosuppressive therapy, and even radiation therapy. Conjunctivitis, uveitis, and scleritis alone or in combination commonly occur.

Lower respiratory tract involvement Lung involvement may be absent at the onset of disease or present dramatically as diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. One third of pulmonary lesions noted on imaging studies [see Figure 4] are asymptomatic (CT scanning is more sensitive than radiography). Nodules often undergo necrosis leading to cavity formation. Bronchospasm is not characteristic of WG. If airway obstruction is suspected, bronchoscopy should be considered to exclude endobronchial or subglottic stenoses. It is frequently necessary to rule out infectious causes of the pulmonary infiltrates, and bronchoscopy is useful in this regard. However, tissue obtained from trans-bronchial biopsy is usually of insufficient quantity to confirm the pathologic diagnosis of WG.

Open lung biopsy is often the optimal method for demonstrating the typical pathologic findings of WG and for excluding malignancies and atypical infections. Typical open lung biopsies9 may contain areas of necrosis, frequently in a broad pattern; giant cells in the parenchymal tissue; and vasculitis. Not all histopathologic features may be present in the same biopsy section. Because these findings may also occur in chronic mycobacterial or fungal infections, special stains and cultures for these agents are essential.

Glomerulonephritis Glomerulonephritis is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in WG. Its presence or absence defines the generalized or limited forms of the disease.

Table 3 Clinical Features of Vasculitis

|

Disorder |

Common Target Organs |

Special Pathologic Features |

Special Laboratory Studies |

Comments |

|

Microscopic polyangiitis |

Nerve, glomerulus, lung (small vessels), GI tract |

No giant cells, vasculitis, proliferative GN (no or rare immune deposits*) |

p-ANCA (antimyeloperoxidase) |

Rule out hepatitis B and C |

|

Polyarteritis nodosa |

Nerve, GI tract |

Arteritis of medium muscular arteries, no giant cells, no GN |

No ANCA |

No small vessel involvement; rule out hepatitis B and C |

|

Wegener granulomatosis |

Upper airway, eye, lung (small vessels), glomerulus, nerve, musculoskeletal system |

Giant cells, geographic necrosis, mild eosinophilia, vasculitis, proliferative GN (no or rare immune deposits) |

c-ANCA (anti-PR3) |

Chronic sinus or ear disease |

|

Churg-Strauss syndrome |

Nerve, lung infiltrates, heart, skin |

Giant cells, eosinophilia, vasculitis, proliferative GN (no or rare immune deposits) |

Eosinophilia ±ANCAs |

Positive atopic history |

*Presence of immune deposits suggests possible hepatitis B or C infection.

ANCA—antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

c-ANCA—cytoplasmic

ANCA GN—glomerulonephritis

p-ANCA—perinuclear

ANCA PR3—proteinase 3

Glomerulonephritis is often aggressive, or it may be relatively indolent. It may be clinically and pathologically indistinguishable from idiopathic rapidly progressive crescentic glomeru-lonephritis, and it is usually clinically silent. The evolution from subclinical to dialysis-dependent renal disease may occur over several weeks. Glomerulonephritis may be present at the outset of the disease, or it may develop only after the patient has been ill with an apparently limited form of the disease. The importance of frequent microscopic urinalyses in the initial and follow-up evaluation of patients with WG cannot be overemphasized. Especially in elderly or debilitated patients, valuable information may be obtained by occasional 24-hour urine collections, which can establish a more accurate estimate of the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) than that provided by the serum creatinine measurement. Renal biopsy may reveal focal and segmental glomerulonephritis with variable glomerular proliferative changes, crescent formation, and necrosis, in the absence of significant immune complex deposition. Although supportive of the diagnosis of WG, these findings are not diagnostic of the disease, and renal biopsy is not the preferred study to confirm the specific diagnosis of WG.

Additional clinical manifestations Musculoskeletal involvement occurs in over half of patients with WG. Symptoms may include arthralgias or arthritis; these symptoms may be migratory, additive, or of fixed distribution. Rheumatoid factor is frequently present in patients with WG, and it may cause diagnostic confusion with rheumatoid arthritis when joint symptoms are significant. The joint disease of WG only rarely produces bone erosions. Neurologic signs and symptoms occur in fewer than 50% of patients, peripheral neuropathy in fewer than 20%, and involvement of the central nervous system in fewer than 10%. Oculomotor defects may occur because of impingement by a retro-orbital mass or sinus disease. Gastrointestinal ischemia and ulcerations are infrequent but may be confused with inflammatory bowel disease, especially because the latter can be associated with ANCA (usually perinuclear ANCA, or p-ANCA). Up to 50% of WG patients exhibit cutaneous involvement with pur-pura, panniculitis, or ulcerations. The activity of the skin disease generally parallels systemic disease activity.

Laboratory Tests

Unexplained chronic inflammation of the respiratory tract or eye or the presence of glomerulonephritis is consistent with the diagnosis of WG. The probability of WG is increased when multiple organ involvement is present, upper airway disease is destructive, and pulmonary nodules (especially with cavities) are demonstrated by radiography. Any combination of organ involvement is possible, but most patients exhibit upper airway involvement at the time of diagnosis.

If the entire clinical picture is compatible with WG and if alternative diagnoses have been appropriately ruled out, the finding of circulating cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA) with anti-pro-teinase 3 specificity is sufficient to make the provisional diagnosis and initiate therapy without a tissue diagnosis. Approximately 20% of patients with WG may have p-ANCA with an-timyeloperoxidase specificity. If there are any atypical features or special concerns regarding the initiation of immunosuppres-sive therapy or if the patient does not respond appropriately to therapy, histopathologic confirmation of the diagnosis is mandatory. The presence of ANCA is not equivalent to the presence of vasculitis; ANCAs can be found in other diseases. The ANCA level is not a reliable means to follow disease activity.10-12 Because WG generally requires therapy with a glucocorticoid plus a cyto-toxic agent, it should be distinguished from other inflammatory disorders, including other vasculitic syndromes [see Table 3], which may be effectively treated with a less toxic regimen.

Treatment

Initial treatment of generalized WG virtually always requires dual-drug immunosuppressive therapy. Corticosteroids may produce symptomatic improvement in the upper airway, lungs, skin, and musculoskeletal system, but tapering usually results in a flare in the disease. Acutely serious disease, particularly renal disease that is progressing, is treated initially with corticosteroids and daily cyclophosphamide with subsequent tapering of the corticosteroids over several months. Many authors recommend that once remission is achieved, cyclophos-phamide therapy should be replaced by methotrexate or aza-thioprine therapy for an additional 12 months of therapy [see Table 2]. There are some strong relative contraindications to the long-term use of cyclophosphamide, including bladder dysfunction (increased risk of drug metabolite-induced cystitis and bladder cancer) and leukopenia. In milder or limited WG, weekly doses of methotrexate (0.20 to 0.30 mg/kg, adjusted for renal function) with folic acid or leucovorin may be substituted for cyclophosphamide. Patients undergoing treatment with im-munosuppressives must be continuously monitored for flares in disease, opportunistic infections, and side effects. Flares may be more frequent in patients treated with methotrexate than in those receiving longer courses of cyclophosphamide.12 Side effects include cytopenias and drug-induced pneumonitis. Methotrexate may cause hepatitis, marrow suppression, and, on rare occasions, cirrhosis. It should be avoided in the setting of renal insufficiency or alcohol use. Some authors have suggested using trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as adjunctive therapy for the treatment of WG and for prevention of bacterial infections that may promote flares of upper airway disease. This approach remains highly controversial. Administration of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole three times weekly is useful in protecting patients against P. carinii pneumonia while they are receiving intensive immunosuppressive therapy. Local nasal and sinus toilet and otolaryngoscopic evaluations are a routine part of the care of patients with upper airway disease. Prophylactic measures to prevent osteoporosis should always be considered when corticosteroids are used on a long-term basis.

Churg-Strauss Syndrome

Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS), or allergic granulomatosis angiitis, is a rare syndrome that affects small to medium-sized arteries and veins in association with bronchial asthma.

Diagnosis

Clinical Manifestations

CSS displays clinical similarities to WG in terms of organ involvement and pathology, especially in patients with upper or lower airway disease or glomerulonephritis. It can follow a rapidly progressive course. CSS differs most strikingly from WG in that the former occurs in patients with a history of atopy, asthma, or allergic rhinitis, which is often ongoing. In the pre-vasculitic atopy phase, as well as during the systemic phase of the illness, eosinophilia is characteristic and often of striking degree (> 1,000 eosinophils/mm3). When eosinophilia is present in WG, it is usually more modest (~500 eosinophils/mm3).

Systemic features of CSS include some combination of pulmonary infiltrates, cardiomyopathy, coronary arteritis, pericarditis, polyneuropathy (symmetrical or mononeuritis multiplex), ischemic bowel disease, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, ocular inflammation, nasal perforations, glomerulonephritis, cutaneous nodules, and purpura.13,14

The patchy pulmonary infiltrates of CSS are often transient and may be associated with alveolar hemorrhage. Pulmonary nodules are uncommon and rarely cavitate. Pleural effusions are common and often contain abundant eosinophils. Clinical distinction from hypersensitivity pneumonitis, allergic aspergillo-sis, and pulmonary lymphoma is at times difficult. Several cases of CSS have been reported to have occurred after the introduction of inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase and while patients with chronic bronchial asthma are being weaned off corticosteroids.

Cardiac disease can be severe and is a leading cause of mortality. Valvular heart disease is not as striking or as common as it is in the idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. Neurologic involvement occurs in more than 60% of patients. Such involvement may be severe; it is generally attributable to arteritis. Cutaneous purpura, urticaria, polymorphous erythematous eruptions, and nodules occur. Gastrointestinal involvement resulting from ischemic vasculitis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, or both may cause pain, cramping, and diarrhea.