Candidiasis

Clinical Presentations

Oral candidiasis One form of oral candidiasis, thrush, appears as white to gray patches (pseudomembranes) on the tongue, soft palate, gingiva, oropharynx, and buccal mucosa. Removing the material from the mucosal surface reveals an underlying erythematous base. Predisposing factors in adults include diabetes mellitus, use of systemic or local corticosteroids, use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, use of radiotherapy or chemotherapy, and impaired cell-mediated immunity, especially from HIV infection. Acute atrophic candidiasis especially follows antibiotic therapy and causes painful, red, denuded lesions of the mucous membranes; the tongue may have ery-thematous areas with atrophic filiform papillae. In chronic atrophic candidiasis, contamination of dentures with Candida causes painful, red, and sometimes edematous lesions with a shiny, atrophic epithelium and well-demarcated borders where the dentures contact the mucous membranes. Poor dental hygiene and prolonged use of dentures are common predisposing factors. Some patients with these predisposing factors have angular cheilitis (perleche), characterized by erythema and fissuring of the corners of the mouth. Other contributing conditions are maceration from excessive salivation or licking, poorly fitting dentures, and a larger fold from diminished alveolar ridge height. Candida is present in most, but not all, patients with this disorder.

Chronic hyperplastic candidiasis (candidal leukoplakia) consists of irregular, white, persistent plaques on the tongue or mucous membranes that are difficult to remove; this form of candidiasis occurs especially in male smokers. Soreness, burning, and roughness of the affected areas are the usual symptoms. Candidiasis of the tongue can also take the form of median rhomboid glossitis, a diamond-shaped area of atrophic papillae in the central portion of the lingual surface.

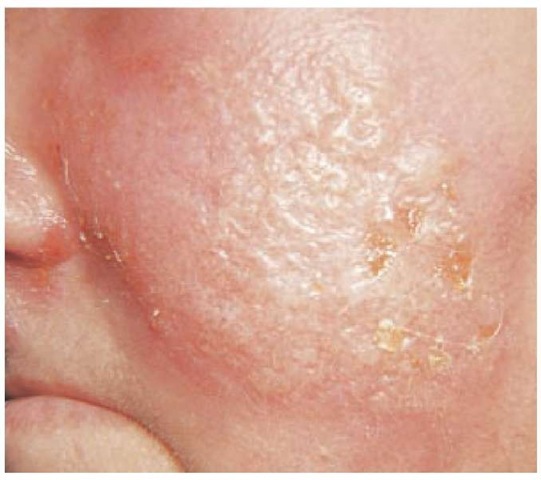

Candidal intertrigo Candida infection may occur in any skin fold, causing soreness and itching. Obese patients are especially vulnerable. Commonly affected areas include the groin, inframammary regions, and folds of the abdominal pan-nus. The lesions are patches of bright erythema accompanied by maceration and an irregular, scalloped border, beyond which papules and pustules (satellite lesions) commonly form [see Figure 5].

Candidal vulvovaginitis and balanitis Most women with candidal vulvovaginitis have no underlying disease, but candi-dal vulvovaginitis may accompany diabetes mellitus and HIV infection. Candidal vulvovaginitis causes white plaques on a swollen, red vaginal mucosa; a creamy vaginal discharge; and erythema, sometimes with pustules, on the vulvar skin. Soreness and burning are common symptoms. Male sexual partners of women with candidal vulvovaginitis—especially male sexual partners who are uncircumcised—may develop balani-tis, characterized by erythema, pustules, and erosions on the glans of the penis. Balanitis may occur spontaneously as well.

Candidal paronychia and nail infection Maceration of the tissue surrounding the nail, typically caused by excessive moisture, may cause paronychia, which is characterized by erythema, swelling, and pain of the nail fold with loss of the cuticle [see Figure 6]. Candida organisms often colonize the area but are probably pathogenic only when pus forms. With chronic colonization, nail involvement may occur, producing yellowish discoloration and separation of the nail plate from the nail bed (onycholysis). For chronic paronychia without purulence, topical corticosteroids, such as triamcinolone cream applied twice daily for 3 weeks, are the best therapy.10

Figure 5 Prominent satellite lesions of discrete vesicles are seen in a patient with candidiasis.

Figure 6 In a Candida paronychia, seen on this patient’s thumb, the nail fold becomes red, swollen, and painful. Nail dystrophy is also seen.

Diagnosis

Scrapings from cutaneous or mucous membrane lesions may be mixed with KOH solution and examined under the microscope for budding yeasts with pseudohyphae. Gram stains of the same specimen are easier to evaluate because they disclose very large, oval, gram-positive cocci that may demonstrate budding or pseudohyphal formation. These organisms are much larger than bacteria and are much easier to see on Gram stain than on KOH preparation. Culture of specimens may be useful if the microscopy is normal or ambiguous. These organisms grow rapidly on both fungal and conventional bacterial media.

Treatment

Oral candidiasis For oral candidiasis, topical nystatin suspension, 200,000 to 400,000 units three to five times a day, is usually effective; an alternative treatment is clotrimazole troches. For patients in whom topical treatment is ineffective or poorly tolerated, systemic therapies include ketoconazole, 200 mg/day; fluconazole, 100 mg/day; and itraconazole, 100 mg twice a day. Angular cheilitis usually responds to an azole cream, such as miconazole or clotrimazole. Dentures should be cleaned carefully with an effective disinfectant, such as chlorhexidine.

Candidal intertrigo and balanitis Candidal intertrigo and balanitis respond to a topical azole cream, such as miconazole or clotrimazole.

Candidal vulvovaginitis Treatment of vulvovaginitis includes a topical azole in the form of a cream, suppository, or ointment, administered intravaginally, typically once daily for 7 days. A cream may be used for vulvar involvement. An alternative to suppositories is treatment with a single oral dose (150 mg) of fluconazole, which is at least as effective as topical therapy and is often preferred by patients.

Candidal paronychia Patients with candidal paronychia should keep their fingers dry; when wet work is unavoidable, patients should use cotton liners under rubber gloves. Prolonged topical therapy with creams or solutions of various azole preparations, such as clotrimazole, is often necessary to eradicate the infection.

Clinical Presentations

Tinea versicolor (pityriasis versicolor) Because the term tinea traditionally refers to dermatophyte infection, some clinicians prefer the term pityriasis, which means scaling, for this yeast infection. Usually asymptomatic, tinea versicolor may cause itching or skin irritation. The lesions are small, discrete macules that tend to be darker than the surrounding skin in light-skinned patients and hypopigmented in patients with dark skin. They often coalesce to form large patches of various colors (versicolor) ranging from white to tan [see Figure 7]. Scratching the lesions produces a fine scale. This infection most commonly involves the upper trunk, but the arms, axillae, abdomen, and groin may also be affected. Most lesions fluoresce a yellowish color under a Wood light.

Malassezia folliculitis (Pityrosporum folliculitis) In folli-culitis, inflammation of the hair follicle causes red papules and pustules that surround individual hairs. One cause of folliculi-tis is M. furfur. Lesions appear predominantly on the trunk but occasionally occur on the arms as well. The lack of comedones distinguishes the lesion from acne. Pruritus and stinging may be present.

Diagnosis

In patients with tinea versicolor, KOH preparations of scrapings from the lesions demonstrate pseudohyphae and yeasts, which resemble spaghetti and meatballs. This technique is sufficient to establish the diagnosis. The yeast form prevails in fol-liculitis and is easily seen on Gram stain of purulent material from a pustule, appearing as a large, oval, gram-positive coccus that is much larger than bacteria. Biopsies of these lesions show organisms around and within the hair follicle, with accompanying neutrophilic inflammation. The yeasts are best seen with periodic acid-Schiff or Gomori methenamine-silver stain. Because these yeasts form part of the normal cutaneous flora, growth of the organism on cultures from scrapings of the skin surface is not very helpful diagnostically. Culture of the yeast from the pus of folliculitis, however, is definitive, but it requires special media, such as Sabouraud agar with olive oil, to provide the necessary lipids for growth. Growth typically occurs in 3 to 5 days.

Figure 7 Tinea versicolor appears on the chest of this patient as oval, hypopigmented, finely scaling macules.

Figure 8 Vesicopustules or bullae of impetigo rupture quickly and leave an erythematous base covered with a thin, seropurulent exudate. The exudate dries, forming layers of honey-colored crusts.

Treatment

Simple treatment of tinea versicolor and Malassezia folliculi-tis involves applying selenium sulfide shampoo from the chin to the waist and from the shoulders to the wrist, allowing the shampoo to dry, and then washing it off after 10 to 15 minutes. Repeating this regimen after 1 week is usually effective; reap-plication once every few weeks as necessary should prevent relapses, which are otherwise common. With tinea versicolor, scaling resolves promptly, but the pigmentary changes may take weeks to months to disappear. Topical azoles, such as ke-toconazole, miconazole, and clotrimazole, are also effective, but the expense of these drugs makes their use impractical except for small or isolated lesions. For patients who have difficulty applying a topical agent because of physical disabilities or other factors, oral ketoconazole or fluconazole in a single 400 mg dose is an effective alternative. This oral program can be repeated for recurrences.

Bacterial Infections

Skin infections caused by streptococci, staphylococci, or both

Impetigo

Initially a vesicular infection of the skin, impetigo rapidly evolves into pustules that rupture, with the dried discharge forming honey-colored crusts on an erythematous base [see Figure 8]. The lesions are often itchy. Impetigo characteristically occurs on skin damaged by previous trauma, such as abrasions or cuts. Exposed areas are most commonly involved, typically the extremities or the areas around the mouth and nose. Impetigo is usually a disease of young children and is more frequent in hot, humid climates than in temperate ones.

The usual cause is Staphylococcus aureus, but sometimes, Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci) is also present; occasionally, S. pyogenes is the sole organism cultured.11 Some strains of S. aureus elaborate a toxin that causes a split in the epidermis and the development of thin-roofed bullae. In this disorder, known as bullous impetigo, superficial, fragile, and flaccid vesiculopustules form and then rupture, with the exu- date drying into a thin, brown, varnishlike crust. Sometimes, the vesiculopustules are not apparent, and erythematous erosions are the only evident disturbance.

Growth of S. aureus, S. pyogenes, or both from the skin lesions confirms the diagnosis, but cultures are unnecessary in characteristic cases. For treatment of sparse, nonbullous lesions, topical mupirocin ointment applied three times daily for 7 days is as effective as oral antimicrobials. Systemic antibiotics active against both S. aureus and S. pyogenes, such as cephalexin or di-cloxacillin, represent an alternative to topical treatment. For extensive lesions, these antibiotics are preferred to topical therapy, and they are the treatment of choice for bullous impetigo. Because of the superficial nature of these infections, the lesions heal without scarring.

Ecthyma

Ecthyma (from the Greek word ekthyma, meaning pustule) is a deeper infection than impetigo. As with impetigo, S. aureus, S. pyogenes, or both may be the cause. Ecthyma commonly occurs in patients with poor hygiene or malnutrition or patients who have had skin trauma. The lesions, which are often multiple and are most common on the lower extremities, begin as vesicles that rupture, creating circular, erythematous lesions with adherent crusts. Beneath the scabs, which may spontaneously slough, are ulcers that leave a scar when healing occurs. Culture of the ulcer base yields the causative organisms. Treatment should be with an oral antistaphylococcal agent, such as dicloxacillin or cephalexin.

Skin infections caused by streptococci

Cellulitis and Erysipelas

Cellulitis and erysipelas are acute, spreading infections of the skin caused by streptococci of groups A, B, C, and G. Erysipelas involves the superficial dermis, especially the dermal lymphatics, and cellulitis affects the deeper dermis and subcutaneous fat. Erysipelas has an elevated, sharply demarcated border, but differences in the clinical appearances of erysipelas and cellulitis are unimportant and often unclear. The most common sites of infection are the face and lower extremities. The causative organisms may enter the skin at obvious areas, such as traumatic wounds and leg ulcers, or through cutaneous inflammation (e.g., eczema); often, however, no point of entry is apparent. Edema from any cause, including venous insufficiency, hypoalbuminemia, and lymphatic damage, is a predisposing factor. Infection commonly occurs on skin that has been permanently damaged by burns, trauma, radiotherapy, or surgery. For example, cellulitis may occur at the site of a saphenous vein removal for cardiac or vascular surgery months to years after the procedure.12 An important predisposing factor in patients with cellulitis or erysipelas is tinea pedis, especially interdigital involvement; streptococci can invade the skin at sites of tinea pedis through adjacent skin surface disrupted by the fungal infection or can migrate to more proximal locations on the leg and enter through abnormal skin there. Obesity is also a predisposing condition.13

Diagnosis Cutaneous findings include rapidly expanding erythema and swelling of the skin [see Figure 9], sometimes accompanied by proximal streaks of redness, representing lymphangitis, and tender, enlarged regional lymph nodes. Vesicles, bullae, petechiae, and ecchymoses may occur. The cuta-neous surface may resemble the skin of an orange (peau d’or-ange) because the hair follicles remain tethered to the deeper structures, keeping their openings below the surrounding superficial edema and creating the characteristic dimpling of the skin.

Figure 9 Erythema, edema, and sharp demarcation of the lesion from the normal surrounding skin characterize facial erysipelas.

On the face, the typical location is on one or both cheeks, with a butterfly pattern of erythema and swelling. Extension to the eyelids, ears, or neck is common. Systemic symptoms, such as fever, headache, and confusion, can accompany these infections; sometimes, such symptoms precede by hours any cutaneous findings on examination. Other patients have no systemic features despite severe skin abnormalities.

The diagnosis is largely clinical; in a typical case, cultures are unnecessary and usually unrewarding. Needle aspiration of the lesion yields an isolate in about 5% of specimens, as do blood cultures in febrile patients. Because of their low yield, blood cultures are unrewarding in typical cases of cellulitis.14 Punch biopsies of the skin are culture-positive in about 20% of cases.15 These results, together with serum antibody tests for strepto-cocci16 and immunofluorescent studies of skin biopsies,17 indicate that streptococci cause the vast majority of cases of cellulitis and erysipelas. S. aureus is often suspected but rarely implicated in cellulitis in the absence of an abscess or penetrating injury. Additional circumstances in which organisms other than streptococci are likely to be responsible for cases of cellulitis include immunodeficiency, penetrating trauma, immersion injuries in freshwater or saltwater, granulocytopenia, and animal bites or scratches. Cultures are appropriate in these situations.

Treatment Treatment consists of elevation of the affected area to help reduce edema and administration of systemic antibiotic therapy. For patients who do not have serious systemic illness, oral treatment is satisfactory. Penicillin is the drug of choice for streptococcal infections; for outpatients who may not take an oral medication as prescribed, I.M. benzathine penicillin G in an adult dose of 1.2 million units provides a complete course. Instead of penicillin, many clinicians prescribe an anti-staphylococcal agent—either a first-generation cephalosporin or a penicillinase-resistant penicillin—because of concerns about S. aureus. Patients often get worse shortly after therapy, with further extension of the cellulitis, higher fever, greater toxicity, and increased white blood cell counts, presumably because rapid killing of the organisms releases potent enzymes, such as strep-tokinase and hyaluronidase, that cause many of the clinical features. Oral prednisolone, taken for 8 days in doses of 30 mg, 15 mg, 10 mg, and 5 mg, with each dose taken for 2 days, decreases the duration of cellulitis and shortens hospital stay; it is a reasonable regimen in those with no contraindications to systemic corticosteroids.18

In patients with leg cellulitis, treatment of tinea pedis is useful in preventing further episodes, which are likely to cause permanent lymphatic damage and can lead to lymphedema and further risk of infection. Other measures to diminish the frequency of future attacks include control of edema by diuretics or mechanical means, such as elastic stockings, and, for those with frequent episodes, prophylactic antibiotics. The easiest approach is the administration of oral penicillin or eryth-romycin, 250 mg twice daily.