Dyspnea

Background

Dyspnea refers to difficulty with breathing and can occur with a wide variety of cardiac, pulmonary, and systemic conditions [see Table 5]. Dyspnea can be classified as occurring (1) at rest, (2) with exertion, (3) during the night, awakening a patient from sleep (paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea), or (4) during episodes of recumbency (orthopnea). Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea and orthopnea result from similar mechanisms. Specifically, the recumbent position augments venous return to the right heart. This increase in cardiac filling further increases the pulmonary capillary pressure and results in interstitial (and possibly intra-alveolar) pulmonary edema. Patients find relief by sitting upright, which reduces venous filling and transiently decreases the pulmonary interstitial pressure.

Dyspnea may be acute or chronic. An acute presentation suggests a pulmonary embolism, acute asthma exacerbation, pneu-mothorax, or rapidly developing pulmonary edema, as occurs with ischemic mitral regurgitation. Chronic dyspnea suggests heart failure resulting from systolic or diastolic dysfunction.

History and physical examination

The history will often exclude less likely conditions and establish the etiology of dyspnea. A history of reactive airway disease, bronchodilator use, or corticosteroid use suggests asthma. Reactive airway disease tends to occur in children and young adults; therefore, in older patients given this diagnosis, a cardiac cause for dyspnea (e.g., new onset of congestive heart failure) should be considered. A significant history of tobacco use, wheezing, chronic cough, and sputum production suggests obstructive airway disease.19 A recent history of fever, chills, and productive cough may indicate bronchitis or pneumonia.

|

Table 5 Causes of Dyspnea |

|

Cardiac |

|

Valve disease |

|

Aortic stenosis |

|

Aortic regurgitaion |

|

Mitral stenosis |

|

Mitral regurgitation |

|

Myocardial disease |

|

Hypertensive heart disease |

|

Dilated cardiomyopathy |

|

Restrictive cardiomyopathy |

|

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy Pericardial disease |

|

Constrictive pericarditis |

|

Pericardial tamponade |

|

Pericardial effusion |

|

Coronary disease |

|

Myocardial infarction and ischemia |

|

Arrhythmia |

|

Ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias |

|

Congenital heart disease |

|

Pulmonary |

|

Reactive airway disease |

|

Chronic obstructive lung disease (chronic bronchitis and emphysema) |

|

Interstitial lung disease |

|

Infection (acute bronchitis and pneumonia) |

|

Pulmonary embolism |

|

Chest wall disease |

|

Pleural effusion |

|

Deconditioning |

|

Obesity |

|

Malingering |

|

Psychogenic |

|

Anxiety and panic disorders |

|

Anemia |

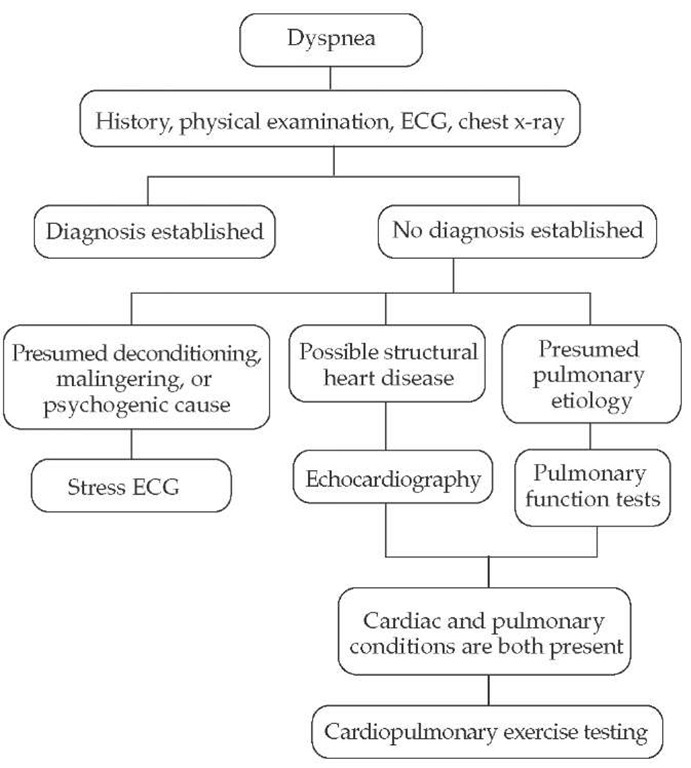

Figure 2 Evaluation of patients with dyspnea. (ECG—electrocardiogram)

The acute onset of dyspnea associated with pleuritic chest pain after a period of immobilization suggests pulmonary embolism. Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, nocturia, recent weight gain, and lower extremity edema suggest a cardiac cause for dyspnea. Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may also awaken at night with dyspnea, but they usually have a history of sputum production and expectoration that improves with the patient in the upright position. Occasionally, on the basis of the history alone, it may not be possible to determine whether a cardiac or pulmonary cause of dyspnea is present.20 In up to one third of patients being evaluated, dyspnea may have more than one cause.21 In elderly patients, dyspnea may be the only symptom of a myocardial infarction. Hemoptysis may indicate the presence of severe underlying pulmonary disease (e.g., pulmonary embolism or lung cancer) but must be differentiated from hematemesis and na-sopharyngeal bleeding.

Several findings on physical examination can assist in excluding a cardiac cause for dyspnea. These findings include a normal level of the jugular venous pressure, a normal point of maximal cardiac impulse, the lack of a third heart sound or cardiac murmurs, the absence of rales on lung examination, and the absence of peripheral edema. Alternatively, elevated jugular venous pressure, a displaced point of maximal cardiac impulse, a third heart sound, a holosystolic murmur of mitral regurgitation, basi-lar rales, and peripheral edema suggest congestive heart failure. A positive abdominojugular reflux maneuver may also identify dyspnea of cardiac origin.22

Obese patients and those with chest wall deformities may experience dyspnea secondary to the increased workload of breathing from the mechanical limitation imposed on the chest wall. Patients with emphysema frequently have an increased an-teroposterior chest diameter, prolonged expiratory phase, expiratory wheezes, and diminished breath sounds. Central cyanosis, a normal anteroposterior chest diameter, and expiratory wheezes or rhonchi on lung examination suggest chronic bronchitis. Expiratory wheezing can occur in both cardiac and pulmonary conditions and is therefore not helpful in establishing an etiology. Stridor may result from an upper airway obstruction or vocal cord paralysis and at times may resemble wheezing. Tachypnea, a loud pulmonic component of the second heart sound, and calf tenderness suggest a pulmonary embolism.

Diagnostic tests

An ECG and a chest roentgenogram should be the initial tests in the evaluation of dyspnea. Pertinent ECG findings include Q waves (prior myocardial infarction), a bundle branch block (structural heart disease), left ventricular hypertrophy (aortic stenosis, hypertension), and evidence of atrial chamber enlargement (valvular heart disease). Notable chest roentgenogram findings include an enlarged cardiac silhouette; interstitial or alveolar edema (congestive heart failure); aortic valve calcification (valvular heart disease); lung mass (lung cancer); focal infiltrate (pneumonia); pleural effusion (congestive heart failure, infectious process); and hyperinflation, bullae, and flattened hemidiaphragms (emphysema). Screening laboratory tests may be useful to exclude anemia as a potential cause of dyspnea.

If the diagnosis of dyspnea remains unclear, additional testing can be pursued [see Figure 2]. For patients with cardiovascular risk factors, with findings on physical examination that suggest structural heart disease, or with abnormal ECGs, echocar-diography is indicated to exclude valvular heart disease and assess systolic and diastolic ventricular function. Patients with a presumed pulmonary etiology for dyspnea that remains undi-agnosed should undergo pulmonary function testing to exclude reactive airway and restrictive and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Stress-ECG may be useful to objectively evaluate the degree of limitation and may be particularly helpful for patients with presumed deconditioning, malingering, or a psy-chogenic cause for dyspnea. For patients who may have a component of dyspnea from both a cardiac and a pulmonary source, cardiopulmonary exercise testing can be considered. Serum brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels are useful in distinguishing cardiac from noncardiac causes of dyspnea; a BNP greater than 100 pg/ml has a sensitivity of 90% but a specificity of only 73% for establishing the diagnosis of heart failure.23 Other factors that affect BNP levels include renal failure, acute coronary syndrome, and female gender.

Palpitations

Background

Palpitations are a nonspecific symptom associated with severity ranging from an increased awareness of the normal heartbeat to life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias [see Table 6]. Although palpitations represent one of the most common complaints requiring evaluation in the outpatient setting,24 consensus guidelines describing the appropriate evaluation have not yet been established.

For patients with an underlying cardiac disease associated with palpitations, long-term outcome is poor. In contrast, clinical outcome is excellent for those with a noncardiac origin for palpitations, despite a high rate of recurrent episodes.25 The key, then, in the evaluation of palpitations is to establish or exclude the presence of underlying structural heart disease. This determination can often be made by use of information from the history, physical examination, and ECG, but it may require additional evaluation with ambulatory ECG monitoring and possibly electrophysiologic testing. Psychiatric illnesses (anxiety, panic, and somatization disorders) account for a certain number of patients who seek medical attention for palpitations25; these disorders can initially be screened by use of simple and rapid patient-administered questionnaires. Although an underlying psychiatric illness should be considered in appropriate patients, it does not obviate the need for a complete evaluation to exclude a cardiac origin.26 A diagnostic algorithm is presented that utilizes a rational approach to diagnostic testing [see Figure 3].

History and physical examination

Palpitations are often described as a fluttering, a pounding, or an uncomfortable sensation in the chest. Occasionally, patients may complain only of a sensation of awareness of the heart rhythm. Patients may be able to discern whether the episodes are rapid and regular or rapid and irregular. Tapping a finger on the patient’s chest in either a regular or an irregular manner may occasionally lead to an accurate description of the events.

A history of palpitations since childhood suggests a supra-ventricular arrhythmia and possibly an atrioventricular bypass tract, such as in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Patients with congenital long QT syndrome typically begin to manifest symptoms in adolescence. A family history of sudden cardiac death, congestive heart failure, or syncope may suggest an inherited dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Knowing the circumstances in which palpitations occur may be useful in determining their origin. Palpitations associated only with strenuous physical activity are normal, whereas episodes occurring at rest or with minimal activity suggest un-derlying pathology. Episodes associated with a lack of food intake suggest hypoglycemia, and episodes after excessive alcohol intake suggest the toxic effects of alcohol.

Table 6 Causes of Palpitations

|

General Category |

Prognosis |

|

Hyperdynamic state |

Anemia, thyrotoxicosis, and exercise—all leading to sinus tachycardia |

|

Increase in cardiac stroke volume |

Aortic regurgitation, patent ductus arteriosus |

|

Arrhythmia Ventricular |

Frequent ventricular premature beats, ventricular tachycardia |

|

Supraventricular |

Frequent atrial premature beats, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, multifocal atrial tachycardia, atrial tachycardia, atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia, atrioventricular reentry tachycardia |

|

Psychiatric |

Anxiety, panic, or somatization disorder |

The resolution of symptoms with vagal maneuvers (breath-holding or the Valsal-va maneuver) suggests paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. The onset of an episode of palpitations on assuming an upright position after bending over suggests atrioventricular nodal tachycardia.27 Emotional stress and strenuous exercise may precipitate episodes in patients with long QT syndrome. Palpitations associated with anxiety or a sense of doom or panic suggest, but do not confirm, an underlying psychiatric disorder. An odds-ratio analysis found that regular palpitations, palpitations experienced at work, and those affected by sleeping were more likely to indicate cardiac origin.28

Figure 3 Evaluation of patients with palpitations. Patients with a potential substrate for arrhythmias include those with prior myocardial infarction, dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or significant valvular or congenital heart disease. (ECG— electrocardiogram; EF—ejection fraction; EP— electrophysiologic)

|

Table 7 Medications Associated with Prolongation of the QT Interval |

|

|

Antibiotics |

Other cardiac drugs |

|

Tetracycline |

Bepridil |

|

Erythromycin |

Gastrointestinal |

|

Trimethoprim and |

Cisapride |

|

sulfamethoxazole |

Antifungal drugs |

|

Pentamidine |

Ketoconazole |

|

Antihistamines |

Fluconazole |

|

Terfenadine |

Itraconazole |

|

Astemizole |

Psychotropic drugs |

|

Diphenhydramine |

Tricyclic antidepressants |

|

Antiarrhythmic agents |

Phenothiazines |

|

Quinidine |

Haloperidol |

|

Procainamide |

Resperidone |

|

Disopyramide |

Diuretics |

|

Sotalol |

Indapamide |

|

Amiodarone |

|

|

Dofetilide |

|

Symptoms associated with an episode of palpitations should also be explored. Syncope or presyncope after an episode suggests ventricular arrhythmias. However, patients with structural heart disease (e.g., severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction) may also experience these symptoms after supraventricular arrhythmias because of dependence on atrial filling. Additional mechanisms of syncope in patients with supraventricular arrhythmias have also been reported.29 Regardless of the mechanism, syncope and presyncope are worrisome symptoms and merit a complete cardiovascular evaluation. Occasionally, patients may experience an episode of polyuria that follows the palpitations. This condition may suggest supraventricular arrhythmias as the cause of palpitations, although studies have found this to be uncommon.30

The physical examination should focus on establishing whether underlying structural heart disease is present. Evidence of cardiac enlargement, third heart sound, and holosystolic murmur of mitral regurgitation suggest an underlying dilated cardiomyopathy. A midsystolic click, often followed by a systolic murmur, indicates mitral valve prolapse, which may be associated with both ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias. A midsystolic murmur along the left sternal border that varies in intensity with alterations in left ventricular filling (e.g., Valsalva maneuver or changes in body position) is consistent with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Although atrial fibrillation is common in hypertrophic cardiomy-opathy, ventricular arrhythmias may also occur.