1925-1961

Lumumba, the son of a poor peasant, was born in Onalua (near Katako-Kombe, in East Kasai, Congo) on July 2, 1925, when Congo was under Belgian colonial rule. During his primary school years, Lumumba ran away or was expelled from several missionary institutions. But at the same time, he was ambitious and driven by real intellectual hunger. On arriving in Stanleyville (now Kisangani) in July 1944, he attended evening classes and became a voracious reader. He was employed in the postal service, but also had an active public life outside of work.

Lumumba became the founder and president of several Congolese cultural, social, and political organizations, including the local Amicale Liberale. In this capacity, he met the Belgian Minister of Colonies, Auguste Buisseret, when the latter was visiting Congo in 1954. Thanks to the minister’s help, he participated in a delegation of Congolese visiting Belgium in 1956—a rare privilege for a black person at the time. Upon his return, Lumumba was arrested on the charge of theft while performing his duties as a postmaster. He was sent to jail and lost his job. However, these events did not break his spirit, nor impact his growing popularity among the Congolese.

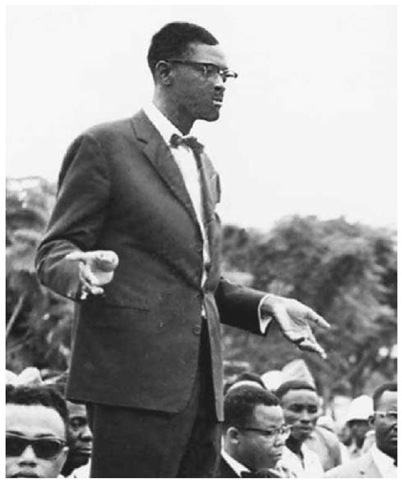

Patrice Lumumba (1925-1961). Patrice Lumumba, leader of the Congolese National Movement, addresses troops in Stanleyville, July 18, 1960.

After his release, in June 1957, he went to the capital, Leopoldville (Kinshasa), where he found a job as a salesman for a local brewery. More than ever before, Lumumba engaged in public and even outright political activities. In October 1958 he was co-founder and provisional president of the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC), which immediately became one of the most influential formations of nascent Congolese nationalism. In December 1958, he participated in the Pan-African Conference at Accra (Ghana’s capital). In July 1959 internal disagreements led to the split-up of the MNC into two rival organizations, Lumumba’s wing being more radical.

The so-called MNC-Lumumba was one of the few Congolese parties being organized on a non-ethnical basis; it stressed the necessity of Congolese unity, as opposed to confederalist or separatist tendencies. In a climate of growing hostility toward Belgian colonial rule, Lumumba was arrested once again after riots in Stanleyville in October 1959. On January 21, 1960, he was condemned to six months’ imprisonment, but was released a few days later so he could attend the Round Table Conference, held in Brussels, where the Belgian government discussed the political future of the Congo with all Congolese parties. This conference decided to grant the country a quick and unconditional independence on June 30, 1960.

In the meantime, parliamentary elections were being held in May; they established MNC-Lumumba as the single most important party of Congo, but without gaining an absolute majority. Consequently, Lumumba became prime minister of the first Congolese government, while Joseph Kasavubu (1910-1969), the leader of another important party, the Abako, was designated as president. During the official ceremonies, held in Leopoldville on independence day in the presence of Belgian King Baudouin (1930-1993) and several prominent Belgian politicians, Lumumba caused serious turmoil by delivering an unannounced speech in which he stressed the many sufferings the Congolese had undergone during Belgian domination. This incident confirmed to the Belgian authorities and other Western powers, such as the United States, that Lumumba was a dangerous and extremist leader.

He was seen as a real threat to Western influence and as a promoter of communist rule throughout the entire African continent. Only five days after independence was declared, a rebellion in some units of the Congolese army led to unilateral Belgian military intervention and widespread chaos in the country. Moreover, the rich mining province of Katanga broke away from central authorities and declared its own independence. This secession was (in practice) supported by the Belgians. Lumumba’s central government broke off diplomatic relations with Belgium and called for international help. This led to a United Nations (UN) intervention in Congo. By now the political and, in some circles even physical, elimination of the Congolese prime minister had become a priority for the Belgian and U.S. authorities.

Inspired by them, President Kasavubu dismissed the prime minister on September 5, 1960; Lumumba, in turn, immediately deposed the president. This political stalemate led Colonel Mobutu (1930-1997), then head of the Congolese National Army and protege of Washington, DC, and Brussels, to take over power.

Lumumba, arrested and placed under home surveillance by Mobutu’s troops (but protected by UN soldiers), made an unsuccessful attempt to escape to Stanleyville, where he could count on many followers. After his capture, Lumumba was finally handed over to his fiercest enemies, the secessionist authorities of Katanga. Only a few hours after his transfer to Katanga’s capital, Elisabethville (now Lubumbashi), during which he was severely beaten and tortured, he was executed nearby on January 17, 1961.

The news of his death caused great indignation in many third world countries and in the Soviet bloc. The elimination of Congo’s legal chief of government was seen as a plot of Western imperialist powers to curtail growing African and third world self-determination. Although the Belgian and U.S. authorities denied any participation in Lumumba’s assassination, presented as an intra-Congolese affair, it is clear by now that both Western powers contributed to create the context leading to his elimination, without directly carrying it out. Immediately after his death, Lumumba became an icon of the third world’s struggle against imperialism—even if he had been prime minister for only two months and not given much opportunity to exercise power.