The final wave of European naval exploration reached Japan’s shores in 1543 when a group of Portuguese traders landed on the island of Tanegashima, south of Kyushu. Merchants and missionaries from across Europe followed soon after. Eminent among Japan’s early visitors was the Spanish Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier (1506— 1552), who began a mission that resulted in the conversion of thousands of Japanese. An incalculable mixture of piety and desire for foreign commerce even led some daimyo (domain lords) to convert; the most famous, Omura Sumitada (1533-1587), opened the port of Nagasaki to foreign trade in 1571. By the end of the sixteenth century, Dutch, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, and English traders and missionaries were common sights in the port towns and harbor cities of Japan; they were known as ”red hairs” or ”southern barbarians.”

For those ambitious warlords who sought to reunify Japan during this tumultuous ”Warring States” period, however, the Christian faith was a threat to be eradicated. The general Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598) sowed the first seed of Japan’s ”closed country” (sakoku) policy when he ordered the Jesuits to leave the country in 1587; although he did not enforce this edict, Hideyoshi made up for laxity a decade later with the ordered execution of twenty-six martyrs.

TOKUGAWA PERIOD

In the years surrounding the reunification of Japan under the Tokugawa shogunate in 1600, a series of edicts were announced that served to drastically reduce Japan’s connection to the world beyond its shores. Relations with any country unwilling to separate missionary from merchant activity were severed (Spain, Portugal); Japanese were forbidden from traveling and trading abroad, or from building seafaring ships; and all contact between foreign countries and the daimyo domains was prohibited, thus establishing a shogunate monopoly on foreign relations.

In the end, only the Dutch and the Chinese were allowed to maintain their trading bases in Nagasaki. The former were quarantined on the small artificial island of Dejima, while the latter were similarly sequestered on shore (the Dutch trade paled in comparison to that of China: 700 Dutch ships made port during the entire Tokugawa era, while the Chinese trade brought in 5,500 ships in that same period). While Japanese society was in many ways self-contained for most of the Tokugawa period (1603-1868), there existed opportunities for the Japanese to sate their curiosity for foreign knowledge. In fact, prospective students of such ”Dutch studies” as Western medicine, shipbuilding, astronomy, chemistry, geography, mathematics, physics, ballistics, metallurgy, gunnery, botany, and so forth flocked to Nagasaki as that city’s reputation as an information hub spread.

The late eighteenth century marked a gradual turning point with regard to Japan’s seclusion policy. As the global power of the Dutch faded, other counties that had benefited from the industrial and bourgeoisie revolutions of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries rose to take their place on the high seas. In the 1790s the Russians attempted to expand into northern Japan, while in the years that followed European whale- and gun-ships appeared in the southern harbors of Kyushu. Furthermore, whaling vessels sailing from the east coast of the United States had been entering Japanese waters since the early part of the nineteenth century, and after the acquisition of the California and Oregon territories in the 1840s (and the subsequent discovery of gold in 1848 to 1849), the country was determined to push westward toward the Pacific.

COMMODORE PERRY AND THE “BLACK SHIPS”

In 1853 a naval fleet under the command of Commodore Matthew Perry (1794-1858) was dispatched from Norfolk, Virginia, by the American government to request that Japan provide for the safety of shipwrecked sailors, as well as to allow the establishment of coaling and watering stations for American ships in the Pacific. Though unstated, the primary impetus for the Perry mission was to explore Japan’s possibilities as a market for excess American industrial manufactures.

Upon his arrival in Japan in July 1853, Perry delivered a letter from President Millard Fillmore (18001874) to the Japanese government requesting first, the right to protect shipwrecked Americans who might possibly wash up on Japanese shores, and second, the right of American ships to stop in Japan to refuel (coal) and acquire provisions. After delivering the letter Perry announced that he and his party would return the following spring with a much larger force, if necessary, to receive an answer to Fillmore’s request.

The head of the shogun’s Council of Elders (effectively the head of the national government, as the shogun himself was a cipher) consequently ordered the coastal defenses around Edo (now Tokyo) Bay to be built up, and quickly moved to act on the requests of the Perry letter. Domestic opinion in Japan on the matter ran hot in both directions; some felt that the country was overdue to open itself to the West, while several influential hardline traditionalists advocated attacking the ”black ships” upon their return. Within the upper echelons of government, opinion was also very divided, and the death of the twelfth shogun Ieyoshi in late 1853—coupled with the ensuing succession debate—did not help in the matter. The Council of Elders therefore recommended that Perry’s demands be accepted.

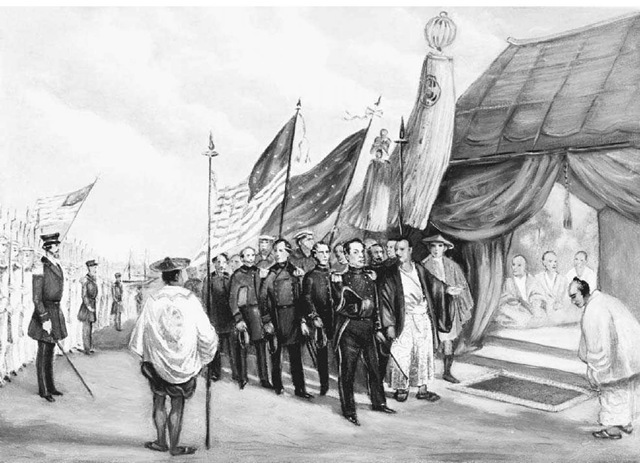

Commodore Perry Meets the Japanese Royal Commissioner. Commodore Matthew Perry of the U.S. Navy meets the royal commissioner at Yokohama, Japan, in 1853. Perry concluded the United States-Japan Friendly Treaty in 1854, ending Japan s longstanding isolationist policy and giving the United States preferential status as a trading partner.

TRADE TREATIES AND OPEN PORTS

Perry returned on February 14, 1854, with double the squadron of the previous year. After several weeks of negotiations, a treaty was signed on March 31, 1854. Titled the ”Treaty of Peace, Amity, and Commerce,” the treaty allowed for American ships to dock at the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate, and for Americans to travel into Japan’s interior up to a distance of 29 kilometers (18 miles) from each. It also promised humane treatment of shipwrecks, and accepted the eventual posting of an American consul in Shimoda.

The Treaty of Kanagawa, as it came commonly to be known, was soon extended to France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Russia. In 1856 U.S. consul general Townsend Harris (1804—1878) established residence in Shimoda and began negotiations on a commercial treaty with the shogunate. Harris’s labors paid off in the signing of a treaty, and by 1858 trade relations between Japan and the Western powers were firmly established. The year 1859 witnessed the foundation of the ”treaty port” of Yokohama for foreigners to reside and conduct business, and within a few years several other ports (including Nagasaki, Kobe, and eventually even Edo) were opened. Japan’s ”closed country” period, such as it was, had officially ended.