The Dutch were late entrants in the Atlantic. Only in the late sixteenth century did Dutch merchants become involved in shipping and trade between Europe, Africa, and the Americas. Within less than two decades, however, the Dutch were important players in the Atlantic. In several towns in the provinces of Holland and Zeeland, merchants had established small companies for the gold and ivory trade with West Africa and the fur trade with North America. Private ship owners sent their vessels to the coasts of South America and the Caribbean islands in search of dyewood and salt. As the Atlantic commerce expanded, the small trading companies and private ship owners were vulnerable to the hostility of Spain and Portugal.

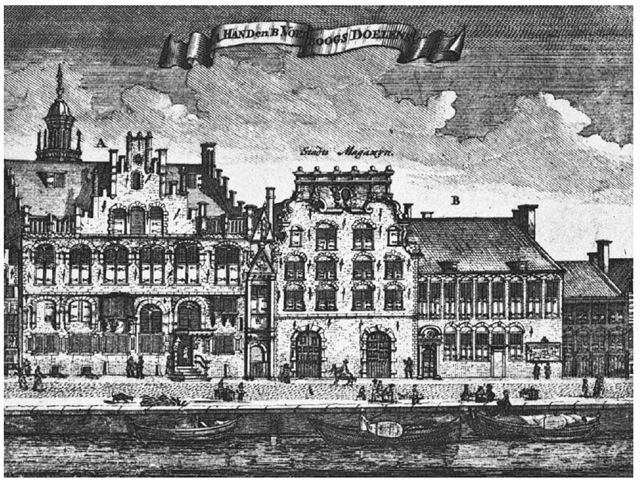

The West India Company’s House in Amsterdam. This illustration, published in 1693, shows the offices of the Dutch West India Company on the Cingel (or Singel) canal in Amsterdam, Netherlands.

On the other hand, stiff competition between merchants was eroding profits at home. In an effort to avoid the decline of the trade, the States of Holland started negotiations designed to achieve collaboration instead of competition. At first, commercial rivalry between the provinces of Holland and Zeeland prevented plans to establish a West India Company to conduct trade with Africa and the Americas. However, during the Twelve Years’ Truce (1609-1621), new plans were made, and after a long debate, the Dutch West India Company (WIC) was finally constituted by the Dutch States-General (parliament) on June 3, 1621.

ORGANIZATION

According to its charter, the Dutch West India Company held a monopoly in shipping and trade in a territory that included Africa south of the Tropic of Cancer, all of America, and the Atlantic and Pacific islands between the two meridians drawn across the Cape of Good Hope and the eastern extremities of New Guinea. Within this territory the States-General authorized the WIC to set up colonies, to sign treaties with local rulers, to erect fortresses, and to wage war against enemies if necessary.

Like the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or VOC), the WIC was based on shareholders’ capital, which was initially 7.1 million guilders. The company had a federal structure with five chambers: Amsterdam, Zeeland, Rotterdam, West-Friesland, and Groningen. While each chamber was run by its own directors, company policy was set by a central board of directors known as the Heeren XIX (the nineteen gentlemen). Directors of the chambers appointed representatives for each meeting of the Heeren XIX, and the composition of the board reflected the value of capital invested by the chambers. Meetings of the Heeren XIX were held two or three times per year to plan the outfitting of war fleets and merchantmen, to fix the value of cargoes, and to oversee the company’s financial state, on which the payment of dividends to the shareholders was based.

ACTIVITIES

While the main objective of the WIC was to establish and defend a commercial network in the Atlantic, in practice it spent more money on privateering and war against Spain and Portugal. In 1623 the Heeren XIX developed strategies, the so-called grand design, to damage Spanish and Portuguese interests in the Atlantic and take control wherever possible. The defenses of the Spanish colonies were too strong to risk attack, but intensive privateering in the Caribbean was a good alternative. Between 1623 and 1636, the WIC captured or destroyed 547 enemy ships, including the legendary conquest of a Spanish silver fleet in 1628 by Admiral Piet Heyn (1577-1629).

Portuguese possessions in South America and West Africa, on the other hand, were less well defended, and the company’s directors and the States-General agreed on a ”grand design” that encompassed the conquest of Salvador, an important center of sugar cultivation in Portuguese Brazil; Luanda in Angola, the most important slave-trade station in Africa; and the Portuguese stronghold Sao Jorge da Mina (Elmina) on the Gold Coast. The first attempt to achieve these goals failed. From 1623 to 1625 several war fleets left the Dutch Republic to attack Portuguese colonies and settlements in the Atlantic, but none of these attacks succeeded.

In 1630 the company launched a second ”grand design” that was more successful. Between 1630 and 1654, the company occupied the northern provinces of Brazil. Especially under count Johan Maurits van Nassau (1604-1679), governor of Dutch Brazil from 1636 till 1644, the export of sugar and dyewood reached a peak. During his governorship, about 28 million guilders worth of Brazilian products were shipped to the Netherlands.

The increasing demand for slaves in Brazil also spurred the Dutch to try once more to capture Luanda. In 1641 Admiral Cornelis Jol (1599-1641) left Recife with a fleet of twenty-one ships and a military force of 2,100 men for Africa. Jol captured not only Luanda but also the sugar-growing island of Sao Tome. The WIC failed to take full control of these African territories, however, and lost them in 1648. In Brazil, military defeat was also at hand. After Johan Maurits left the colony, a rebellion of Portuguese planters ended the period of prosperity, finally leading to the capitulation of the Dutch in Brazil in 1654.

The WIC was more successful in capturing the Portuguese forts and factories on the Gold Coast from 1637 to 1642. These possessions, which remained Dutch until 1872, made it possible to control the Guinea trade for a long period. Between 1623 and 1674, the company shipped more than 320,000 ounces of gold and an unknown quantity of ivory, wax, and other tropical products to the Dutch Republic.

In addition to privateering, war, and commerce, the WIC colonized parts of the Guyana coast and a few Caribbean islands. The plantation colonies on the Guyana coast remained small until the end of the seventeenth century. In the Caribbean, the most important colony was Curasao, which was occupied by the WIC in 1634. Initially the island was used as a naval base, but from the 1650s it served as an important depot for the commodity trade and the slave trade with the Spanish mainland colonies. Between 1630 and 1674, the WIC shipped approximately 84,000 slaves from Africa to Brazil, the settlements in Guyana, and Curasao.

The drive for colonies and the long years of war against Spain and Portugal, however, had exhausted the WIC’s capital and brought it close to bankruptcy. From the 1650s the WIC was haunted by financial problems that made it almost impossible to invest in a solid trading network in the Atlantic. When several plans to reform the company failed, the States-General finally decided to dissolve the WIC in September 1674.

THE SECOND WEST INDIA COMPANY

The States-General, however, were convinced that the Dutch Republic’s interests in the Atlantic were best served by a chartered company, so it decided to establish a new WIC on the very day the old one disappeared. At first sight, the transformation from the old to the new company seemed little more than a debt redemption program with some minor organizational adjustments. Nevertheless, there were significant differences between the two companies. The old company was not only a trading organization and administrator of Dutch colonies, but also an instrument of war against Spain and Portugal. The second WIC, on the other hand, was primarily a commercial organization interested in the commodity trade with West Africa and the transatlantic slave trade.

Among the Dutch colonies in the company’s territory, Suriname was most important, but the directors had little control over it. From 1683 the colony was owned by the Suriname Corporation (Societeit van Suriname), in which three parties participated: the WIC, the city of Amsterdam, and Cornelis van Aerssen van Sommelsdijck (1637-1688). Sommelsdijck was a descendant of a Dutch aristocratic family. Thanks to his share in the chartered Socieeteit van Suriname, he would be the first governor of the colony under the new arrangement. To the west of Suriname, there were three smaller Dutch plantation colonies on the banks of the rivers Berbice, Demerara, and Essequibo, of which the first mentioned was owned by a shareholders company.

The slave trade to the Guyana colonies and Caribbean islands, however, remained under company control until the 1730s. Between 1674 and 1739, the WIC shipped approximately 187,000 slaves from Africa to the colonies in the west. Not only the transatlantic slave trade, but also the commodity trade with West Africa, was an important source of income for the company. It exported more than half a million ounces of gold and approximately three million pounds of ivory from the Gold Coast between 1676 and 1731. But in 1730 the monopoly was partly lifted by the States-General and in 1734 totally abandoned. During the 1730s the company competed with private merchants. Finally, however, the directors decided to stop the transatlantic slave trade and to minimize the commodity trade with West Africa.

Even when the company withdrew from active participation in trade, it continued to play the role of intermediary and protector for private Dutch trade in the Atlantic region. The WIC was an extension of the strongly decentralized Dutch government. With its limited powers, it carried out administrative and defense functions needed to keep the colonies afloat, and many private individuals benefited in the process. In 1791, when the decentralized Dutch Republic also was at the point of disintegration, the WIC was eliminated. Soon thereafter, its ”big brother” in Asia, the VOC, met the same fate. The properties of the two large trading companies became colonies of the Netherlands in the early nineteenth century.