As the nineteenth century drew to a close, China found itself reduced to semicolonial status: The Qing state remained intact, but most of China was divided into spheres of influence under the control of foreign powers, a process that had begun with the first Opium War (1839-1842) and concluded with the first Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). Although the Qing continued to stumble along for another decade, what accelerated the process of dynastic collapse was the Boxer Uprising. Known collectively as the Boxers United in Righteousness (Yihequan) and sharing the belief that spirit possession and invulnerability rituals would protect them from bullets, a motley crew of peasants, laborers, and drifters launched the movement in 1898. From their origins in northwestern Shandong, the Boxers spread across the North China Plain, extending as far as Manchuria and Inner Mongolia.

A combination of deteriorating conditions in the countryside and increasing Chinese resentment of the missionary presence in Shandong fueled the Boxer movement. The North China Plain had been hard hit by a series of natural disasters; banditry, smuggling, and corruption also were rife in the area. The devastation caused by flood and drought coupled with the government’s failure to effectively address the crisis made the impoverished peasants easy recruits for the Boxer movement. Furthermore, missionary activity in the area and the special privileges accorded to Chinese converts exacerbated relations between the Chinese on the one hand, and the Christian missionaries and their converts on the other. The physical assault of missionaries and Christian Chinese as well as the destruction of railroad and telegraph lines—symbols of the Western presence in China—defined the Boxer Uprising as an antiforeign, anti-Christian, and anti-missionary movement.

However, the Boxers were not anti-Qing as is sometimes thought; after all, their slogan was ”Revive the Qing; destroy the foreigner.” And despite later representations portraying the Boxers as rebels, the Qing court did support the Boxers. Although the rumor that the Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) had ordered the expulsion of all foreigners and Chinese Christians proved to be false, she did declare war on all eight foreign powers on June 21, 1900. Early interpretations maintain that the Boxers were initially against the Qing, being an outgrowth of secret societies with a tradition of rebellion against the state. However, later studies indicate that the Boxers were pro-Qing from the outset, based as they were on local militia loyal to and under the supervision of the Qing. In his study of the origins of the Boxer Uprising, historian Joseph Esherick agrees with the latter interpretation, but dismisses the Boxers’ sectarian and loyalist origins, emphasizing instead their genesis in popular culture.

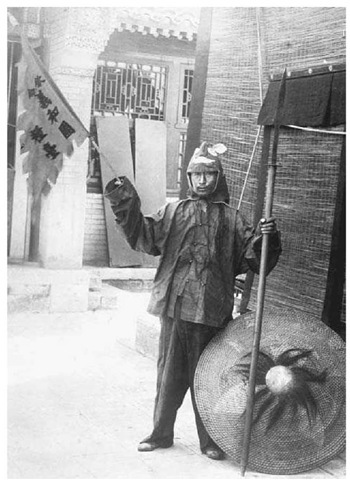

Chinese Rebel During the Boxer Uprising, 1900. A Chinese rebel waves a banner in support of the Boxer Uprising, a violent rebellion against foreign interests in China.

The Boxer Uprising peaked in the summer of 1900 with the siege of the foreign legation quarters in Beijing and the Qing court’s declaration of war against the foreign powers. It took an eight-nation alliance to end the siege. The Boxer Protocol in 1901 demanded that China pay a huge indemnity in the amount of 450 million taels (equivalent to about $333 million at the time); by some estimates, that amount would total a billion taels in 1940 when the indemnity was to be paid in full. In 1908, the United States allocated its portion of the indemnity to fund scholarships for Chinese students. Through its ”open door notes,” the primary objective of which was to protect American commercial interests in China, the United States also sought to slow down if not thwart the scramble for concessions. The Qing state emerged from the Boxer Uprising a weaker, if not fatally crippled, country unable to hold onto the reins of power without foreign assistance. To restore peace and order, American troops occupied Beijing; historian Michael Hunt attributes the smoothness of the American occupation to Chinese collaborators.

For the mainland Chinese, the Boxer event has held different meanings at different times. During the New Culture Movement (1915-1925), the Chinese viewed the Boxers as ignorant peasants blinded by xenophobia and bound by superstition; later, the rising tide of nativism and nationalism reconfigured the Boxers’ anti-foreign sentiment as patriotic fervor. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), the Chinese Communist Party mythologized the Boxers as revolutionary vanguards.