Algeria’s significance in the history of Western colonialism can be seen in four stages. In Algeria the transition from medieval and early modern (in the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries) to modern and contemporary interactions (in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries) between Europe and the southern Mediterranean is particularly visible. Algeria was the scene of both the beginning (1830) and the end (1962) of the second French colonial empire. Algerians experienced both a more far-reaching colonial rule than was imposed elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa, and a more protracted and bitter struggle for decolonization. From the 1950s into the 1970s Algeria was a model of national liberation and third-world self-assertion, and then a striking example of the disintegration of these projects since the 1980s.

THE OTTOMAN REGENCY

Algeria was politically unified within its principal modern boundaries as a province ofthe Ottoman Empire. Declining North African dynasties and the expansion of Spanish and Portuguese power in the early sixteenth century produced regional instability in which conflicts between European and Muslim powers in the Mediterranean were still thought of as continuations of medieval holy wars. An adventurer from the Aegean, Khayr ad-DTn (d. 1546), known to Europeans as Barbarossa, received support from the Ottoman sultan Selim I (1467-1520) to fight the Spanish and their local allies in North Africa, and established himself at Algiers as governor general of North Africa in 1517. He removed local dynasties in eastern and western Algeria and defeated Charles V (1500-1558), the Holy Roman emperor, before Algiers in 1541. The Ottomans exercised a nominal sovereignty over the province.

After 1587 governors from Istanbul were named to three-year postings, but they became dependent on the military garrison (ocak) of Algiers and the ruling council of notables. From the 1670s the ocak combined with the guild of privateer captains (ta’ifat al-ra’is), who controlled the major part of the city’s income, to appoint the ruler with the Turkish title of bey, effectively an autonomous sovereign. Although troops still came from Turkey in exchange for tribute every three years, the regency was beyond effective Ottoman control. The economy was based on agriculture and arboriculture by the peasantry (approximately half of the population), livestock raised by nomadic and seminomadic groups, as well as maritime and overland trade and privateering.

Algerian piracy, the main theme of colonial European depictions of the regency, was most successful in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and declined in the eighteenth. From the sixteenth century onward, trading relations with the Netherlands, Britain, and France increased, with European companies establishing commercial presences under capitulation agreements, which accorded special privileges to European consuls and their proteges. In the eighteenth century Algeria was an exporter of grain to Europe—the 1827 diplomatic incident that provided the pretext for the later French invasion originated in a dispute over payments due to Algiers for grain shipped to supply French armies in the 1790s.

CONQUEST AND COLONIZATION

The French expedition of 1830, conceived as a foreign adventure to relieve domestic political pressure, quickly decapitated the Ottoman regime in Algiers and installed a military government. Hesitation over policy in Algeria remained, however, into the 1840s. Treaties concluded with the Algerian leader, the Emir ‘Abd al-Qadir (1808-1883), in 1834 and 1837, limiting the territory under French occupation, but hostilities resumed in 1839, lasting until ‘Abd al-Qadir’s surrender in 1847. In 1848 Algeria was declared an integral part of French territory. Civilian colonization expanded; from around 56,000 in 1850, the European population reached some 130,000 in 1870, owning 765,000 hectares of land, up from some 115,000 hectares in 1850.

Over the same period, the Algerian population declined from an estimated 3 million in 1830 to an official total of some 2.3 million in 1856, and 2.1 million by the end of the wars of conquest and armed resistance in 1872. The Algerian population grew again, however, in the 1870s, and by the 1920s had reached around 5 million, against a European population of around 800,000. By the mid-1950s just fewer than 1 million Europeans dominated the country and Muslim Algerians numbered almost 9 million. The political regime that developed from 1871 onward reflected the tension between the belief in a French Algeria and the demographic insecurity of the colonial settlers; Algerians were considered French nationals, but not full-fledged citizens, and Muslims’ electoral rights were consistently limited to preserve minority rule.

A series of attempts at reform began after World War I (1914-1918), in which some 200,000 Muslim Algerians served in French uniform, and of whom some 98,000 became casualties. The Algerian electorate was expanded, and from 1919 to 1936, politics in the colony revolved primarily around reform proposals by a series of Algerian leaders. At the same time as the development of this liberal and professionally based loyal opposition, which argued for Algerians’ emancipation within the framework of a reformed French state, there also emerged, among the community of migrant workers established since World War I in France, a radical nationalism aimed at separation and independence.

In 1926 the first nationalist organization with a program demanding Algerian independence, the Etoile Nord-Africaine (ENA), or North African Star, was formed in Paris. At the same time as the most significant of the liberal reform projects, advanced by the antifascist Popular Front government in 1936, became stalled in the national assembly, the ENA leader, Messali Hadj Hajd (1898-1974), began to organize the radical nationalist movement in Algeria. The reform programs ultimately failed to restructure the guiding logic of the colonial system. Until 1944 special repressive legislation— the native code (regime de I’indigenat)—criminalized various activities not otherwise illegal under French law, if committed by Algerians.

When parity of parliamentary representation was eventually granted after 1944, Algerians elected the same number of representatives as the European community one-eighth their numbers, and elections up until 1951 were rigged by the administration. The persistence of this repressive system, and massive reprisals against the Algerian population by settler militia and the military after an abortive insurrection at Setif and Guelma in eastern Algeria on May 8, 1945, prepared the ground for the resort to arms by militant nationalists.

THE WAR OF INDEPENDENCE

The nationalist movement created in France in the 1920s gained in popularity through the 1940s. The political organization, the Parti du people algerien (PPA), or Algerian People’s Party, created a paramilitary wing, the Organisation speciale (OS), in 1947, to prepare an armed insurrection. On November 1, 1954, former OS members launched a coordinated series of attacks across Algeria and announced the creation of the Front de liberation nationale (FLN), or National Liberation Front. Denounced as bandits and terrorists by the French authorities, the FLN set about creating a generalized insecurity among Algeria’s Europeans and simultaneously began to construct a counter state to assume power in the name of the Algerian nation. By persuasion and coercion, the FLN gained the upper hand in Algerian opinion, shown by the massive popular demonstrations of December 1960. No mass insurrection occurred, however, after the orchestrated violence of August 20, 1955, when the local peasantry and FLN guerillas killed 71 Europeans in Philippeville (now known as Skikda).

The repression after Philippeville killed over 1,000 Algerians according to official estimates (the FLN claimed 12,000 dead); the cycle of violence thus marginalized remaining moderate forces. The counterinsurgency war eventually involved collective reprisals against civilians, and the systematic use of internment, torture, and summary executions. By the war’s end, some 300,000 Algerians had become refugees, 400,000 were in prison or detention camps, 8,000 villages had been destroyed, and some 3 million people forcibly relocated from the countryside into regroupment centers. Some 300,000 Algerians were killed (the official Algerian figure would be 1 million or 1.5 million). The FLN’s most spectacular offensives, at Philippeville and in the Battle of Algiers (1956-1957), were also military defeats, and by late 1959, the French army had largely regained control of Algerian territory.

An Algerian Cafe. A French colonist receives a shoeshine at a small cafe in Oran, Algeria, during the 1890s.

The political situation created by the war and the FLN’s successful international diplomacy, however, made a negotiated solution inevitable. Brought to power by the army in May 1958, as the savior of the empire after the Algerian crisis precipitated the collapse of the government, Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970) insisted that France would win the war, but, by late 1961, ultimately recognized the need to disengage from Algeria. De Gaulle’s negotiations were opposed by French Algerian ultras, who formed the paramilitary Organisation armee secrete (OAS) to resist decolonization by force of arms. The end of the war was marked by violence between the Gaullist authorities, the OAS, and the FLN. In the Evian accords of March 1962, a cease-fire was agreed, and Algeria became independent later that same year on July 5.

ALGERIA AND THIRD WORLD REVOLUTION

Fighting continued in the first months of independence between rival FLN factions struggling for power. The revolutionary provisional government was ousted by Ahmed Ben Bella (b. 1918), who became Algeria’s first president in September 1962 with the support of the army. Ben Bella’s presidency saw the establishment of a bureaucratic single-party state against which other founding nationalist leaders became dissidents. A spontaneous workers’ self-management movement, though adopted as policy, was bureaucratized and power effectively centralized. In response to purges of the regime, however, the army under Defense Minister Houari Boumedienne (1927-1978) overthrew Ben Bella in a coup d’etat on June 19, 1965. Already an icon of third-world self-assertion through its revolutionary war and under the charismatic Ben Bella, Algeria under Boumedienne became the standard-bearer of the third worldism of the 1960s and 1970s.

Ahmed Ben Bella. Ahmed Ben Bella, shown here in the early 1960s, fought against colonial France as a leader of the Algerian National Liberation Front. In 1963 he became the first president of independent Algeria. ap images.

A statist development program based on hydrocarbon revenues (first tapped in 1958) established an economic infrastructure whose basic industries achieved an average annual growth rate of 13 percent from 1967 to 1978. Foreign holdings were progressively nationalized, culminating in the takeover of 51 percent of French oil interests in 1971. At the nonaligned states’ Algiers summit in 1974, Boumedienne called for a new international economic order in which developing nations should control the extraction, processing, and pricing of their own natural resources. In the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and a member of the Arab steadfastness front opposed to the separate Egyptian peace with Israel in 1978, Algeria maintained a revolutionary and anti-imperialist foreign policy stance. Domestically, dissidence was curbed and the military-security apparatus remained the regime’s backbone, with the FLN party reduced to a powerless administrative instrument. An official nationalist unanimity articulated around Arab-Islamic cultural identity and the mytholo-gizing of the armed struggle as the foundation of the state dominated the public sphere in education and the media.

At the death of Boumedienne in 1978, Chadli Benjedid (b. 1929) became president, and the socialist economic project was precipitately abandoned. State-managed enterprises were dismantled and the ambitious hydrocarbon-led development plan initiated in 1976, and projected to 2005, was cancelled. The growth of middle-class consumption and retreat of state management did not, however, lessen dependence either on oil exports or on food imports, which grew to crisis proportions with the collapse of world oil prices in 1985 and 1986. Annual average gross domestic product (GDP) growth declined from 15 percent between 1978 and 1984 to 3 percent in 1986. Factional struggle between Benjedid and an old guard opposed to market-led reform intensified. In October 1988 riots broke out in Algiers and other cities, signaling the onset of a generalized political crisis.

CIVIL VIOLENCE SINCE 1988

Benjedid hoped to maintain power and push through economic reforms while pluralizing political competition. Constitutional amendments in 1989 allowed for the creation of political parties; municipal elections were held in 1990 and legislative elections in 1991. This sudden opening of politics was most effectively capitalized upon by the Islamist movement, tapping into popular frustration as well as piety and articulating a utopian Islamic solution presented as having been the true aim of the war of independence. When the Front islamique du salut (FIS), or Islamic Salvation Front, swept the first round of parliamentary elections in December 1991 with 81 percent of contested seats (but only 24.6 percent of the registered electorate), the military intervened, forcing Benjedid’s resignation and the suspension of the electoral process. The repression of the Islamists was met by the radicalization of the fringes of the movement and the emergence of extremist armed groups between 1992 and 1994. Through 2000 between 100,000 to 200,000 Algerians are thought to have been killed in the resulting violence.

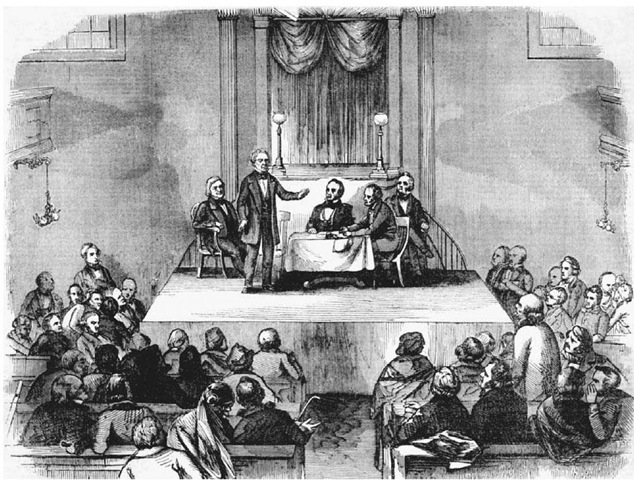

A Meeting of the American Colonization Society. This nineteenth-century engraving depicts a meeting in Washington, D.C., of the American Colonization Society, formed in 1817 by prominent Americans to promote the repatriation and settlement of free blacks in Africa.