INTRODUCTION

The term “blended learning” has become a corporate buzzword in recent years (Lamb, 2001). Recently, the American Society for Training and Development identified blended learning as one of the top ten trends to emerge in the knowledge delivery industry in 2003 (Rooney, 2003). In higher education, the term blended learning is being used with increased frequency in academic conferences and publications. Issues related to the design and implementation of blended learning environments (BLE) are surfacing as technological advances continue to blur the lines between distributed learning and the traditional campus-based learning. Many universities are beginning to recognize the advantages of blending online and residential instruction. The Chronicle of Higher Education recently quoted the president of Pennsylvania State University as saying that the convergence between online and residential instruction was “the single-greatest unrecognized trend in higher education today” (Young, 2002). Along the same lines, the editor of The Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks is predicting a dramatic increase in the number of hybrid (i.e., blended) courses to include as many as 80-90% of the range of courses (Young, 2002). The article provides an overview of blended learning environments (BLEs) and outlines the most common benefits and challenges identified in the research literature.

BACKGROUND

The use of the term “blended learning” is a relatively new phenomenon in higher education. Historically, academicians have referred to blended learning environments (BLEs) as hybrid environments. But with the explosion in the use of the term “blended learning” in corporate training environments, the academic literature has increasingly followed suit, and it is common to see the terms used interchangeably (Voos, 2003). In this section of the article, we address the following two questions:

• What is being blended in a BLE?

• How much to blend in a BLE?

What Is Being Blended?

By nature, both the terms “hybrid” and “blended” imply a mixing or combining of something. It is that something that people do not always agree upon. Some understand blended learning to be a combination of different instructional methods (soft technologies) (Singh & Reed, 2001; Thomson, 2002), while others define blended learning as a combination of different modalities or delivery media (hard technologies) (Driscoll, 2002; Rossett, 2002). Blended learning is most commonly considered to be the combination of two archetypal “learning environments” using both the hard and soft technologies most common in each instructional environment. In short, blended learning environments combine face-to-face (F2F) instruction with computer-mediated (CM) instruction.

Blending occurs at the instructional (or course) level as opposed to the institutional level. A whole body of literature talks about dual-mode institutions that deliver both F2F and distributed instruction, but don’t explicitly blend these environments at a course level (Rumble, 1992). Historically, the on-campus and distributed education branches of dual-mode universities served different populations of learners. However, increasingly the lines between traditional on-campus learners and distance learners are being blurred. This same phenomenon is happening between on-campus course offerings and distributed course offerings. This blurring of boundaries is often referred to as the “hybridization” of the university(Cookson, 2002).

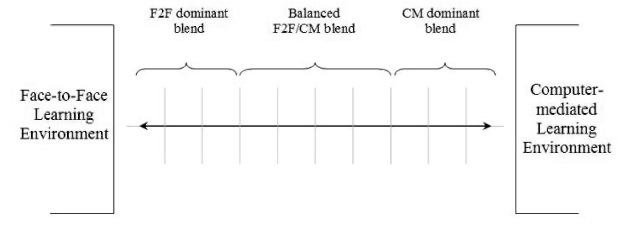

Figure 1. Blended learning environments combine F2F and computer-mediated instruction

How Much to Blend?

As might be expected, no magic blend is optimal for all learning contexts. As Figure 1 suggests, a range of combinations can occur in a blended environment. Figure 1 divides this range into three general levels: blends that have a dominant F2F component, blends that have a dominant CM component, and blends that are fairly balanced in mixing the two environments. In higher education and corporate training, blends of all varieties exist. At the F2F end of the spectrum, many on-campus instructors and corporate trainers are enhancing their courses or training programs by using computer-based technologies. In these instances, the instructors and trainers may change what they do in the F2F environment because of the added CM portion, but they typically do not reduce the F2F contact time. At the computer-mediated end of the spectrum, an increasing number of higher education distributed education courses have a F2F component. These courses range from requiring F2F orientation activities and in-person testing (Martyn, 2003; Schrum & Benson, 2000) to allowing for optional participation in discussion or lecture sessions. In the corporate world, companies often add F2F sessions to e-learning training modules (Bielawski & Metcalf, 2002; Thorne, 2003) to give employees the chance to practice and apply skills and knowledge they’ve gained via the online instruction. In the middle of the spectrum, both university courses and corporate training modules reduce F2F class time by increasing the time the learners spend in online instructional activities.

Why Blend?

There are many reasons why an instructor or corporate trainer might choose to design a BLE over a non-blended environment. The most predominant benefits and challenges in the literature are presented in the following two sections.

Benefits to Blending

The phrase most commonly used by advocates of BLEs is that they allow one to have the “best of both worlds” (Morgan, 2002; Young, 2002). BLEs can also mix the least effective elements of both worlds if they are not designed well. Beyond this general statement, we identified three major themes that are often referred to as reasons for blending: (1) more effective pedagogy, (2) increased convenience and access, and (3) increased cost effectiveness.

More Effective Pedagogy

The opportunity to improve upon prevalent pedagogical practices is one of the most commonly cited possibilities that blending provides. For example, in the on-campus environment much of teaching and learning is still focused on the “transmission” model with the lecture used by 83% of higher education instructors as the predominant teaching strategy (U.S. Department of Education, 2001). Constraints such as class duration, size, and location can provide a formidable barrier to making changes to that strategy. Introducing online instructional components opens the range of instructional strategies that can be used. Proponents of BLEs have mentioned such benefits as:

• an increase in active learning strategies used (Collis, 2003; Morgan, 2002);

• a change from a more teacher-centered to learner-centered focus (Hartman, Dziuban, & Moskal, 1999; Morgan, 2002);

• a greater emphasis on peer-to-peer learning (Collis,2003);

• a change in the way faculty allocate time, allowing for increased mentoring of individual students (Bourne, 1998; Waddoups, Hatch, & Butterworth, 2003); and

• the possibility for interaction with remote experts or remote peer review of projects (Levine & Wake,2000).

In distance education, there is often a similar problem of focusing on “transmissive” rather than “interactive” learning strategies (Waddoups & Howell, 2002). This typically results from making large quantities of information available on the Web for students to learn independently of anyone else. Many learners are not ready for this type of independent online learning and feel isolated in distance learning courses as a result. BLEs are seen as one way to balance independent learning with human interaction (Hartman et al., 1999; Morgan, 2002). Adding a F2F component to a distance course or online training program can improve social interaction and facilitate future online interaction (Willett, 2002). Occasional F2F interaction can also motivate students to discipline themselves in a predominantly online course (Leh, 2002).

Convenience and Access

Many learners want the convenience of a distributed learning environment, yet don’t want to sacrifice the human touch they are used to in the F2F class environment. BLEs are viewed as a way to balance these two factors by increasing convenience, but still maintaining some F2F contact (Collis, 2003; Morgan, 2002). Reducing the amount of F2F seat time reduces time and place constraints for learners (Hartman et al., 1999; Leh, 2002), as well as commuting stress (Willett, 2002) for individuals who travel distances and then have to fight for parking on campuses with large commuter populations.

In corporate settings, increased convenience and access to instructional materials are also compelling reasons for adopting blended learning solutions. Access to training materials was significantly increased when many companies adopted e-learning materials in the form of self-paced computer-based training and Web-based training. However, interaction with fellow learners and instructors was severely limited, if not completely annihilated with the computer-mediated delivery method on its own. As a result, completion rates of e-learning courses often sagged dramatically (Singh & Reed, 2001). Much of the slump has been attributed to the lack of a social, interactive, mentored learning environment. Blended learning approaches are popular because they provide the convenience and accessibility of e-learning environments, while simultaneously promoting personal interaction.

Table 1. Four general categories describing technology use in Pew grant projects

| Technology Use | Description |

| Technology Enhanced | F2F contact time (seat time) is not reduced. Technology may be used to engage learners in activities that were not possible or practical in a F2F classroom (e.g., simulations, online tutorials, individualized assessment and feedback, etc.). Technology may change the nature of the F2F contact (e.g., information transmission via technology enabling discussion rather than lecture in class; change from lecture to tutoring in computer lab, etc.) |

| Reduced Seat Time | F2F contact time is reduced to accommodate time spent in computer-mediated learning activities. |

| Entirely Distributed | Courses that have no F2F contact with instructors or learners and are conducted entirely via the internet or other technological tool. Courses may include both synchronous or synchronous distributed interaction. Courses may be self paced independent study or more collaborative. |

| Distributed with optional F2F sessions | Required components of courses are entirely distributed (see above) but optional F2F sessions can be attended (lectures, discussion sessions, one-on-one lab help, etc.) |

Cost Effectiveness

Cost effectiveness is a third major benefit that can result from using BLEs. On the academic side, The Center for Academic Transformation, with the support from the Pew Charitable Trusts, recently completed a three-year grant program designed to support universities in redesigning their instructional approaches using technology to achieve cost savings and quality enhancements. Grant awards were used in the redesign of large enrollment introductory courses offered at 30 institutions across the U.S. In order to achieve cost savings, many of the redesign efforts transformed traditional F2F lecture-based course offerings to courses with a blend of F2F and CM instruction. Table 1 details four general patterns of technology use identified in the PEW-sponsored courses.

Just as higher educational institutions look for cost savings from BLEs, most corporations that adopt blended learning solutions do so because they are a cost-effective means of training and distributing critical information to employees. Numerous studies indicate that travel costs and time associated with corporate training objectives could be reduced by as much as 85% using blended learning methods (Singh & Reed, 2001). For example, a report on an executive MBA program for mid-career doctors shows that blended learning programs can be completed in half the time and at less than half the cost of classroom based instruction (Jones International University, 2002). Another report on corporate blended learning indicates that blended learning solutions can be cost-effective for companies because they provide a means of reaching a large, globally-dispersed audience in a short period of time with both a consistent and a semi-personal content delivery (Bersin & Associates, 2003).

Challenges to Blending

The current literature tends to focus much more on the positives of BLEs than the challenges that institutions, instructors, and learners face from adopting BLEs. Three major categories of challenges addressed in the literature are: (1) finding the “right” blend, (2) the increased demand on time, and (3) overcoming barriers of institutional culture. These three main challenges will be addressed individually in the following sections.

Finding the Right Blend

The most significant challenge faced by people developing and delivering BLEs is identifying the instructional strategies that match well with the conditions that are present in these two quite different environments. This challenge is complex because it relates to achieving the right blend, both from a learning and cost-effective standpoint.

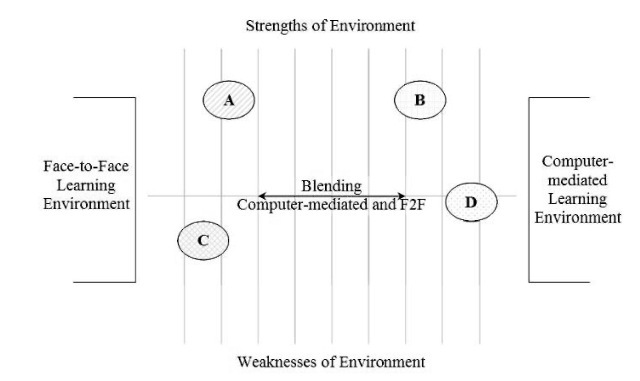

Figure 2. Blending the strengths of F2F and CM learning environments (Adapted from Osguthorpe and Graham, 2003, p.229)

.

.

Both F2F and CM learning environments have affordances that endow them with particular strengths and weaknesses. The affordances enable the effective use of particular instructional methods within the specific learning environment. By blending F2F with CM instruction, the range of possible instructional strategies that can be used is greatly increased. From a pedagogical standpoint, the goal of blending learning environments for a particular context and audience is to find an appropriate combination of the two environments that takes advantages of the strengths of each environment and avoids their weaknesses (Martyn, 2003; Osguthorpe & Graham, 2003). Figure 2 adds a dimension to Figure 1 and shows how blended solutions can either capitalize on the strengths of both learning environments or not. In Figure 2, for example, blends A and B both capitalize on the strengths of both environments while blends C and D use methods in an environment for which they are not well suited.

Increased Demand on Time

Both faculty instructors and corporate trainers are generally comfortable with creating and presenting instructional materials either in a F2F or in a CM learning environment, but not necessarily in both learning environments. When institutions decide to utilize both learning environments for a single course offering, the time demands of the instructor or trainer increase because now instructional materials must be develop for both CM and F2F environments. Additionally, instructors and trainers typically incur an increase in the time they spend interacting with learners in BLEs. When BLEs are instituted, instructors and trainers who have typically only interacted with students in either F2F or CM learning environments now are responsible for interacting with the students in both environments. As Hartman studied BLEs in higher educational institutions, he found that adding an online component to a F2F course put increased time demands and stress on the faculty developing and delivering the blended course (Hartman et al., 1999).

Overcoming Barriers of Institutional Culture

There are cultural barriers for both learners and instructors that must be overcome in order to use BLEs. The CM components of BLEs require a large amount of self discipline on the part of the learners because learning in that setting is largely independent (Collis, 2003). In current higher educational online learning environments, students tend to procrastinate when they have little required contact (Leh, 2002). In corporate settings, many employees don’t finish online courses because they lack the discipline or the motivation to complete the courses. Currently, the culture in both higher educational institutions and corporations allows for student dropouts and don’t necessarily require the learners to have the discipline to finish an online course. If BLEs are to be highly successful, the culture of these organizations, as it relates to persistence, must change.

Another cultural element that can work against the use of BLEs is organizational and management support. In higher educational institutions, faculty may hesitate to try blended approaches because they are not sure that they have departmental support or that it fits into the culture of the department or greater institution (Hartman et al., 1999). Similarly, management support for BLEs is essential if they are to succeed in corporations because executives have a large influence on company culture (Bersin & Associates, 2003).

FUTURE TRENDS

Blended learning environments promise to be an important part of the future of both higher education and corporate training. Over the past decade, with the increased availability of technology and network access, the use of BLEs has steadily grown. However, the amount of research done related to the design and use of BLEs is relatively small and additional research is needed. In particular, research is needed that will help instructors to understand the strengths and weaknesses of methods used in F2F and CM instructional environments and know how to appropriately combine both types of instruction. Cases across various levels and types of blends need to be documented and analyzed in order to better understand the tradeoffs that must be made when designing instruction in a blended learning environment.

CONCLUSION

During the past decade, online learning has made huge strides in popularity in both higher education and corporate sectors of society. The use of technology has increased access to educational resources and facilitated communication in a way that was not previously possible. Despite the strengths that online learning environments provide, there are different strengths inherent in traditional face-to-face learning environments. The current trend toward blending both online and F2F instruction is a positive direction that merits our further attention and study.

KEY TERMS

Affordances: Features of an environment or artifact that “afford” or permit certain behaviors.

Blended Learning Environment: A learning environment that combines face-to-face and computer-mediated instruction.

Distributed Learning Environment: A learning environment where participants are not co-located and use computer-based technologies to access instruction and communicate with others.

Dual-Mode Institution: Institutions that simultaneously offer on-campus courses and distance education courses.

Hard Technologies: Computer equipment, software, networks, and so forth.

Hybrid Course: Another name for a blended course. Typically, a course that replaces some F2F instructional time with computer-mediated activities.

Hybridization: The phenomenon occurring at universities where there is an increasing overlap of the boundaries of traditional on-campus courses and distance education courses.

Soft Technologies: Instructional innovations, methods, strategies, and so forth.