Infusion-Induced Hypothermia

An all too common complication of intravenous infusions is hypothermia. The infusion of large quantities of room-temperature solutions will rapidly cool the body and lead to hypothermia.43,44 If it is necessary to infuse large quantities of solutions, then consideration should be given to providing a warming blanket (hypothermia blanket) or other similar device. Some Paramedics use commercially available blood warmers, special heated compartments or thermal sleeves to warm the intravenous fluids prior to administration. Abbott Corporation, a major supplier of intravenous solutions, recommends the use of a "conventional warm air oven" which warms the fluids before administration. Once the fluids are removed from the oven, they should be used within 24 hours and not re-warmed again.

The use of microwave ovens to warm intravenous solutions is commonly practiced in emergency departments and operating rooms. Caution should be used when microwave ovens are used to warm intravenous solutions because microwave ovens can create "hotspots" of fluid within the solution that, during infusion, could scald the epithelial (inner) lining of the vein.

The use of warm water baths is also not recommended. Water from the warm water bath may cross the plastic flexible container wall and contaminate the solution. Such contamination could lead to a potential pyrogenic reaction.

Removing Intravenous Access

Paramedics may be called upon to remove, or discontinue (DC), an intravenous infusion. A careful step-by-step procedure will minimize pain for the patient and the potential of contamination to the Paramedic. The first step is to clamp the administration set and stop the infusion. With the infusion stopped, the Paramedic should gently loosen any tape that is securing the IV catheter. An alcohol prep pad can be used to undermine the tape’s adhesive. With the tape loose, the Paramedic would then place a small gauze pad over the insertion site and apply gentle downward pressure with the gloved nondominant hand. With the gloved dominant hand, the Paramedic would gently apply traction to the catheter’s hub in the opposite direction of the insertion. With the entire length of the catheter out of the vein, the Paramedic would continue to apply direct pressure to the wound and elevate the limb. If the IV access was in the antecubital fossa, the patient should be encouraged to keep the limb straight and elevate it. Bending the elbow will widen the opening created by the IV catheter and thus increase bleeding. The catheter and administration set should be discarded safely in a biohazard bag and a notation made of the removal of the IV access, including the exact location of the access site.

Intraosseous Access

Before the invention of the plastic IV catheter, venous access was obtained using large metal needles, needles that would be resharpened, sterilized, and reused again and again. These large gauge needles often made venous access in the elderly or the vasculopathic patient difficult to obtain and alternatives were sought to peripheral venous access.

In 1922, Dr. C.K. Drinker, of Harvard University, demonstrated that the use of metal needles inserted into the bone marrow of the sternum (intraosseous (IO)) could provide venous access to the circulation. Dr. Drinker confirmed that these intraosseous infusions rapidly infused into the bone marrow and then later into the central venous circulation.

Later, Dr. Tocantins and Dr. O’Neill expanded on sternal intraosseous access sites and included the long bones (tibia and femur). With multiple sites readily available, and the invention of the bone needle for intraosseous access, IO access became practical and convenient. During the 1940s and 1950s, IO infusion in critically ill patients became somewhat commonplace and was used by military medics in World War II in over 4,000 documented cases.

However, with the advent of plastic catheters and improved venous catheter technology, IO use saw a decline after World War II and remained an historic relic of past medical practice until 1984. In 1984, Dr. Orlowski, after witnessing IO use in children afflicted with cholera in India, wrote an article in the American Journal of Diseases in Children citing the advantages of IO in pediatrics. IO infusion was reborn for pediatrics and is now commonplace. Pediatric IO is discussed in detail at the end of the topic.

More recently, due to a growing population of aged patients, vasculopathic patients, and emerging new medical technologies that hold promise for use in the field, the need for venous access has grown more acute. Therefore, the interest in IO infusion for adults has been revisited.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Long Bones

A long bone has two ends (the epiphyses) and a shaft (the dia-physis). Within the shaft of the bone or the medullary cavity is the bone marrow. At the ends of the bones, within the epiphysis, is the soft, sponge-like cancellous bone. Together the medullary space and the cancellous bone make up the intraosseous space.

The IO space contains a complex network of blood vessels that connect to the major veins of the central circulation via a series of longitudinal Haversian canals that exit the bone and connect directly into the major veins. Infusing fluids into the intraosseous space ultimately infuses fluids into the central veins via these Haversian canals.

Intraosseous Devices

A number of IO devices are presently on the market. These devices range from manually inserted IO needles, the type used primarily in children, to medical drills that create a precise opening for insertion of an IO needle. Because of the large number of IO devices on the market, Paramedics are advised to read the accompanying medical literature that comes with each device and to familiarize themselves with the device by practicing on a manikin or model before trying to utilize the IO in the field.

Indications and Contraindications

There are several indications for adult IO placement. One indication is cardiac arrest.45, 46 During cardiac arrest, the cardiovascular system is in collapse and venous access can be a challenge. Intravenous access can be difficult to obtain or is obtained at a cost of prolonged scene times. The rigid container of the IO, the bone, provides a ready access even during zero blood flow states. Other indications include any time there is a need for an immediate access for medication administration for the patient in extremis.

Advantages of IO access are also several-fold. IO access is rapid, quicker than IV access in many cases, and generally requires less skill and training to master. In one study, IO access was able to be obtained in the field within 20 seconds or less with a 97% success rate.

However, IO insertion is not without its risks. IO insertion can be painful in conscious patients, although that is not always the case. Some patients have compared the pain of an IO insertion to the discomfort of a large bore IV IO infusions can also be painful, but with a bolus of lidocaine can further reduce the pain of infusion. Finally, the IO has a potentially higher risk of osteomyelitis. However, the incidence of osteomyelitis is uncommon. It has been reported that the osteomyelitis rate for IO infusions is about one in 200 cases. Other attendant risks include fat embolism, fracture, extravasation, and compartment syndrome. It should be noted that these complications are rare and can usually be prevented by careful insertion and monitoring.

The single largest drawback to IO may be the inability to infuse large bolus of fluids. The IO infusion is generally similar to that of a 20 gauge IV catheter.51 The addition of a pressure infusion bag enhances flow rates to more acceptable levels.

Intraosseous Placement

Preparation of the IO site is similar to preparation for an IV insertion. First the Paramedic needs to select a site. Depending on the device and the manufacturer’s recommendations, an IO needle can be placed in the sternum, the tibia, the femur, or the humerus. Next, the exact point of placement must be identified, often using adjunct landmarks, and properly prepared with povidone-iodine or similar antiseptic (Skill 27-3).

After inserting the needle, following the manufacturer’s recommendations, the needle should be flushed with 5 to 10 cc of sterile saline to ensure patency. If the patient is conscious, an additional bolus of lidocaine (approximately 10 cc) can help to reduce the pain of infusion.

STREET SMART

Improper placement of an IO needle in an obese patient can be avoided if the Paramedic monitors the insertion. If bone resistance cannot be felt once the needle has been placed to a depth of approximately 5 cm, indicated by a black band on some IO needles, then the needle should be withdrawn and an alternative site prepared.

Medication Administration

The majority of prehospital medications can be administered via the IO route (Table 27-1). The exceptions to IO administration include 9% saline, also known as super saline, and adenosine.

This list includes medications typically used during a cardiac arrest. Considering the speed of attaining therapeutic levels of these drugs via the IO route, IO is considered by most authorities to be preferable over endotracheal administration.

Phlebotomy

A sample of the patient’s blood, for laboratory analysis, may be drawn at the time that the IV access is obtained. However, there are times when a blood sample is required but IV access is not necessary. In this case, a Paramedic would perform a phlebotomy, drawing blood through a straight needle, to obtain the sample.

Table 27-1 List of IO Medications

|

• |

Amiodarone |

• |

Furosemide |

|

• |

Atropine |

• |

Lidocaine |

|

• |

Dextrose 50% |

• |

Naxolone |

|

• |

Diazepam |

• |

Rocuronium |

|

• |

Dopamine |

• |

Succinylcholine |

|

• |

Epinephrine |

• |

Vasopressin |

|

• |

Etomidate |

• |

Vecoronium |

|

• |

Fentanyl |

• |

Versed |

Prior to performing the venipuncture, the Paramedic needs to assemble the necessary equipment, including blood sample tubes. There are a number of blood sample tubes and each has a specific purpose. The color of the stopper indicates a blood tube’s use. The patient’s condition usually dictates which blood tubes will be used and is based upon the expectation that a certain battery of diagnostic laboratory tests will be performed to help discern the pathology and guide the treatment.

The red top tubes are sometimes called clot tubes because the tube contains no additives or preservatives to prevent blood clotting. Without additives, such as an anticoagulant, the blood clots and the serum rise to the top. The percentage difference between the amount of space filled by the clot (formed elements such as red blood cells) and the total volume is the hematocrit. The patient’s hematocrit is an important indicator, particularly for trauma patients.

Samples of the serum are used to test the blood chemistry (i.e., the electrolytes, etc.) in the blood. The clot is used to identify the variety of blood (blood-typing) and to crossmatch it to blood that is available in the blood bank. It is important that the serum separates from the formed elements in the blood; therefore, it is counterproductive to invert or shake the blood tube.

The light blue and lavender-topped tubes have anticoagulants (3.2% sodium citrate and sodium EDTA, respectively) added to them to prevent the blood from clotting. These anticoagulant tubes are used for special clotting studies, such as the partial prothrombin time (PPT), as well as red blood cell studies, including hematocrit and hemoglobin (H&H). The laboratory results from these studies are important if the patient is destined for the operating room or may receive fibrinolytics.

A number of other blood tubes are available—gray, green, royal blue, and yellow—and each has a specific indication. For example, tan-topped tubes have sodium heparin, another anticoagulant, and are used for tests of lead.

When in doubt, or when no orders exist, a standard blood sample usually includes drawing a red-topped tube, a blue-topped tube, and a lavender-topped tube. The order of the blood draw is also important. To prevent potential contamination from additives, the tubes without additives (red-topped tubes) are drawn first and the "wet" tubes (those with additives) are drawn last.

To perform a phlebotomy, the Paramedic could prepare the site as if an IV access was going to be attempted. Frequently, the preferred site for a phlebotomy is the antecubital fossa, although any peripheral vein is acceptable.

Commonly, a straight hollow-bore needle attached to a vacuum tube apparatus is used for phlebotomy. With the vein prepared, the needle shield is removed from the needle and the gloved dominant hand stabilizes the vein. The needle is then advanced, bevel up, into the skin and then the vein, at about a 15 to 20 degree angle. Once the Paramedic is confident that the needle is in the vein, then the blood tube is joined with the sheaved needle inside the barrel and blood is automatically drawn up.

After the first flash of blood occurs, confirming placement, the tourniquet is released and the blood tube allowed to fill completely. Red-topped tubes should be placed aside while other colored-topped tubes are generally gently inverted approximately 10 times, but not shaken, before being set aside. Multiple blood tubes can be filled in this manner.

Once the phlebotomy is completed, a cotton gauze pad is placed over the needle insertion site and the needle quickly withdrawn in the direction opposite of insertion. Cotton balls should not be used as they tend to adhere to and pull out platelet plugs at the insertion site. With the bleeding controlled, the Paramedic can proceed with marking the blood tubes with the name of the patient, the date and time of the phlebotomy, and the Paramedic’s initials.

After placing the blood tubes in a clear plastic bag, the Paramedic should ensure the blood tube’s safe transportation to the receiving hospital. Some Paramedics tape the blood tubes to the outside of the intravenous solution bag. This practice is acceptable provided the contents are clearly visible. The use of a nonsterile glove is discouraged, as the contents inside the glove are not visible. All potentially infectious materials (PIM) must be clearly marked with the biohazard symbol or some other warning that indicates the presence of PIM. A cut sustained from the broken glass of a blood tube is an exposure to blood-contaminated sharps and may be a reportable incident.

Pediatric Phlebotomy

Drawing blood from a child can be a challenge. By applying the principles of pediatric venous access (discussed later in the topic), along with the principles of phlebotomy (just discussed), the Paramedic can expect to have success.

A heel stick is performed to obtain a blood sample from an infant. A heel stick—puncturing the infant’s heel with a lancet then drawing the blood off with a capillary tube—is performed on newborns. Practice while under the careful supervision of a practiced provider is the best means for Paramedics to master this technique.

For older children, phlebotomy is performed as it is on adults, with a few exceptions. Children have smaller veins; therefore, smaller needles (25 g to 27 g) are used to draw blood. Children’s veins also tend to collapse under the pressure that a vacuum tube system produces. Venous collapse can be averted by either using a pediatric vacuum tube system or using a 5 mL or 10 mL syringe attached to a butterfly needle. Gentle intermittent traction on the syringe’s plunger will gradually draw the sample from the vein. With a little patience, the application of age-specific therapeutic interventions, and the right equipment, the Paramedic can expect to be successful with a phlebotomy on a child.

Blood Cultures

When a patient has a fever or the Paramedic suspects that the patient may have septicemia (an infection in the blood), then a blood culture could be drawn. The blood culture is a special laboratory analysis used to test the blood for the presence of sources of infection called pathogens. Common blood culture specimen collection units are either aerobic and anaerobic (Figure 27-29). Blood cultures usually involve obtaining enough blood to fill two broth-containing blood tubes or bottles, the broth being a medium for bacterial growth. One of the blood cultures is used to test for aerobic microorganisms and the other blood culture is used to test for anaerobic microorganisms.

It is important that medical asepsis be practiced whenever a blood culture is drawn. The venous access site must be cleansed with a povidone-iodine-based solution, such as Betadine®, or similar antigermicidal solution and the solution allowed to dry. While the solution is drying on the skin, the Paramedic should take a new swab and cleanse the top of the blood culture tube/bottle. The remainder of the phlebotomy would proceed as usual. Although practices vary from hospital to hospital, in every case medical asepsis is practiced the prevention of accidental contamination of the specimen is important.

Pediatric Intravenous Access

Pediatric intravenous access can be challenging to even the most experienced Paramedic. The key to success in pediatric IV access is to match the IV access site chosen to the urgency of the situation and then take a therapeutic approach to the child that is matched to the child’s developmental level.

The choice for a peripheral pediatric venous access can be very age-dependent, owed to the child’s changing body habitus. For example, an umbilical venous access may be appropriate in a newborn whereas a venous access in the dorsal venous arch of the hand may be more appropriate for a toddler.

Figure 27-29 Blood culture specimen collection units.

Age-Appropriate Approaches to Pediatric Patients with IV Access

Regardless of a child’s age, each child views intravenous therapy as a painful procedure that he would rather avoid. Gaining a child’s trust and cooperation will tend to improve success with pediatric IV access. Trust and cooperation is earned when the Paramedic carries out the child’s IV therapy with an age-appropriate therapeutic approach.

As a general rule, the Paramedic should not separate the child and parent during the IV attempt. However, practice, experience, and personal interaction with the parent is a better basis for that decision. Involving the child in the preparations and decision making may help the child feel more in control, provided the child is not given the opportunity to say no, and helps foster trust between the Paramedic and the child.

The child should never be told, by either the Paramedic or the parent, that the insertion of an IV will not hurt. Rather, the focus should be on the benefit of the IV and how quickly the IV will be over. Needless to say, this places a burden on the Paramedic to ensure that all of the necessary supplies are immediately available and prepared. Similarly, the child should not be told that only one IV attempt will be necessary. The number of IV attempts is a function of the child’s condition and the importance of the IV. Finally, regardless of a child’s age, he should be encouraged to cry, privately, without fear of ridicule, and to express his anger or frustration without fear of judgment. The Paramedic understands that these outbursts are not meant personally. Such expressions are healthy and an indication that the child is coping appropriately with the situation.

Developmentally speaking, infants are learning trust and have a strong child-parent bond. The infant may not trust the Paramedic but does trust the parent to protect him. A parent should be encouraged to comfort the infant before and after the venipuncture. Often a pacifier can help to sooth the infant while the procedure is going on; however, the infant should not be given a bottle-feeding, as the risk of vomiting and aspiration offsets any advantage. If the infant is fussy, and there is a risk of accidental catheter displacement, then a swaddling board (e.g., an infant blanket over a short padded board) may be used to immobilize the infant.

Toddlers exhibit their growing autonomy by attempting to assert their control. The toddler should be dealt with matter-of-factly and told (in simple, age-appropriate terms) what is about to happen. Age-appropriate distractions are often very useful at this age as the child attempts to demonstrate her self-control. However, it is not uncommon for a child at this age to regress. A parent should be available to comfort the child.

Preschoolers are capable of assisting with preparation and setup (e.g., tearing pieces of tape) and want to appear confident. However, preschoolers have a fear of the unknown, particularly about pain. Therefore, they should be told, in a straightforward manner, what is going to occur. This approach helps to eliminate some of the fear-producing fantasy the child might imagine. When the IV access has been obtained, the preschooler should be commended for her cooperation and permitted to express her emotions. Paramedics may be taken back by the articulate manner which the preschooler may express herself.

School-aged children, up to adolescence, are thoughtful and generally understand the implications behind the statements that the Paramedic makes. The Paramedic should encourage the school-aged child to ask questions and then provide answers at an age-appropriate level. Limited decision making, such as determining the arm that the IV is to be started, can help the child feel more in control and less fearful.

Adolescents can be treated like an adult, more or less. Time spent with fuller explanations and a question and answer period helps to gain both their trust and their cooperation. Adolescents are concerned about body image and peer approval. The Paramedic should be forthcoming with praise regarding positive aspects of the relationship and avoid any criticism of the adolescent’s conduct. In some instances, an adolescent may be content to listen to music from a headset while the IV is being started. This is not a demonstration of contempt or aloofness, but rather an effective distraction technique.

Umbilical Venous Access (UVC)

For a newly born, with a medical emergency, it may be possible to gain venous access via the umbilical cord to administer fluids and drugs, such as epinephrine. The umbilical cord, that rope-like appendage between mother and child, has two arteries and one vein, surrounded by Wharton’s jelly, and has no nerves. The two umbilical arteries carry deoxygenated blood from the fetus to the placenta, and the umbilical vein carries oxygenated blood from the mother to the fetus. Some umbilical cords, however, have only two vessels: an artery and a vein. Newborns with only two vessels often have associated congenital anomalies.

To begin, the Paramedic would loosely tie off the umbilical cord, around the base, with cloth umbilical tape. Tying the umbilical tape too tight can prevent the passage of the venous catheter. If the tie is too loose, as evidenced by bleeding, it can be re-tied tighter later. The umbilical stump is now cleansed with a povidone-iodine solution. While waiting for the povidone-iodine solution to dry, the Paramedic would prefill a 5 French umbilical catheter with NSS via a syringe attached to a three-way stopcock (Figure 27-30).

After donning sterile gloves, the Paramedic would take the sterile scalpel and perform a perpendicular transection of the umbilical cord proximal to the clamp. Examination of the cord should reveal three orifices—two arteries and one vein—with the vein typically at the 12 o’clock position. The thicker-walled arteries are usually inferior, at 4 and 8 o’clock, unless the cord is twisted, which is a common presentation.

The umbilical catheter would be advanced through the umbilical vein, the larger orifice, and toward the heart for a distance of approximately 2 to 4 cm. Once the umbilical catheter is past the orifice, there should be a flash of blood inside the catheter. Opening the stopcock, the Paramedic should gently aspirate, by pulling back on the syringe’s plunger, until a free flow of blood is observed.

Figure 27-30 Umbilical catheter attached to a three-way stopcock.

With the catheter now in place, fluids and/or medications (such as 0.1 mg of epinephrine 1:10,000) can be rapidly administered. The Paramedic should tighten the umbilical tie to secure the umbilical catheter in place and prevent excessive bleeding from the umbilical stump.

Scalp Vein Access

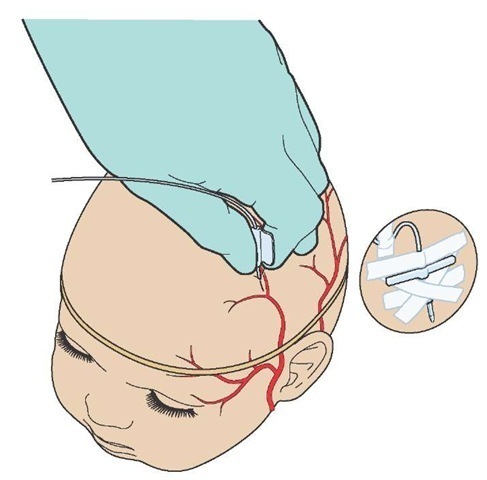

The thought of inserting a needle into an infant’s scalp may sound bizarre to many Paramedics. However, pediatricians and pediatric nurses have used scalp veins for venous access for decades. Scalp veins can provide a reliable venous access that is easy to obtain and even easier to maintain.

The scalp veins are generally very prominent, have no valves to interfere with cannulation, and are only thinly obscured by the fine hair of the infant. The most commonly used scalp veins are the metopic vein, located at the mid-forehead region, and the superficial temporal veins located bilaterally on the forehead (Figure 27-31).52 A broad rubber band placed around the head at approximately ear level will help distend the scalp veins.

The infant should be restrained, as needed, and the area prepared. Using scissors, any negligible amount of hair should be clipped and the area cleansed with povidone-iodine or similar antiseptic solution, using care to not have the solution run into the eyes.

After flushing the intravenous catheter (either a butterfly needle or an over-the-needle device) with sterile saline, the Paramedic would pull gentle traction on the vein with the nondominant hand and proceed with inserting the needle. When a flash of blood is visible, the tourniquet can be removed and a small amount of saline solution injected to test the catheter’s patency and position.

If the saline solution flushes easily, without evidence of infiltration, then the IV catheter should be secured in place.

Figure 27-31 Anatomy of infant scalp veins.

Many Paramedics place a clear plastic cup-like shield over the site to protect it from incidental trauma.

STREET SMART

Infants and children cannot tolerate a fluid overload as well as an adult. Immature kidneys have more difficulty adjusting to the changing electrolytes and fluid osmolarity that occur with a massive fluid infusion. For these reasons, pediatric intravenous infusions are run cautiously and through a burette or an infusion pump in most cases.